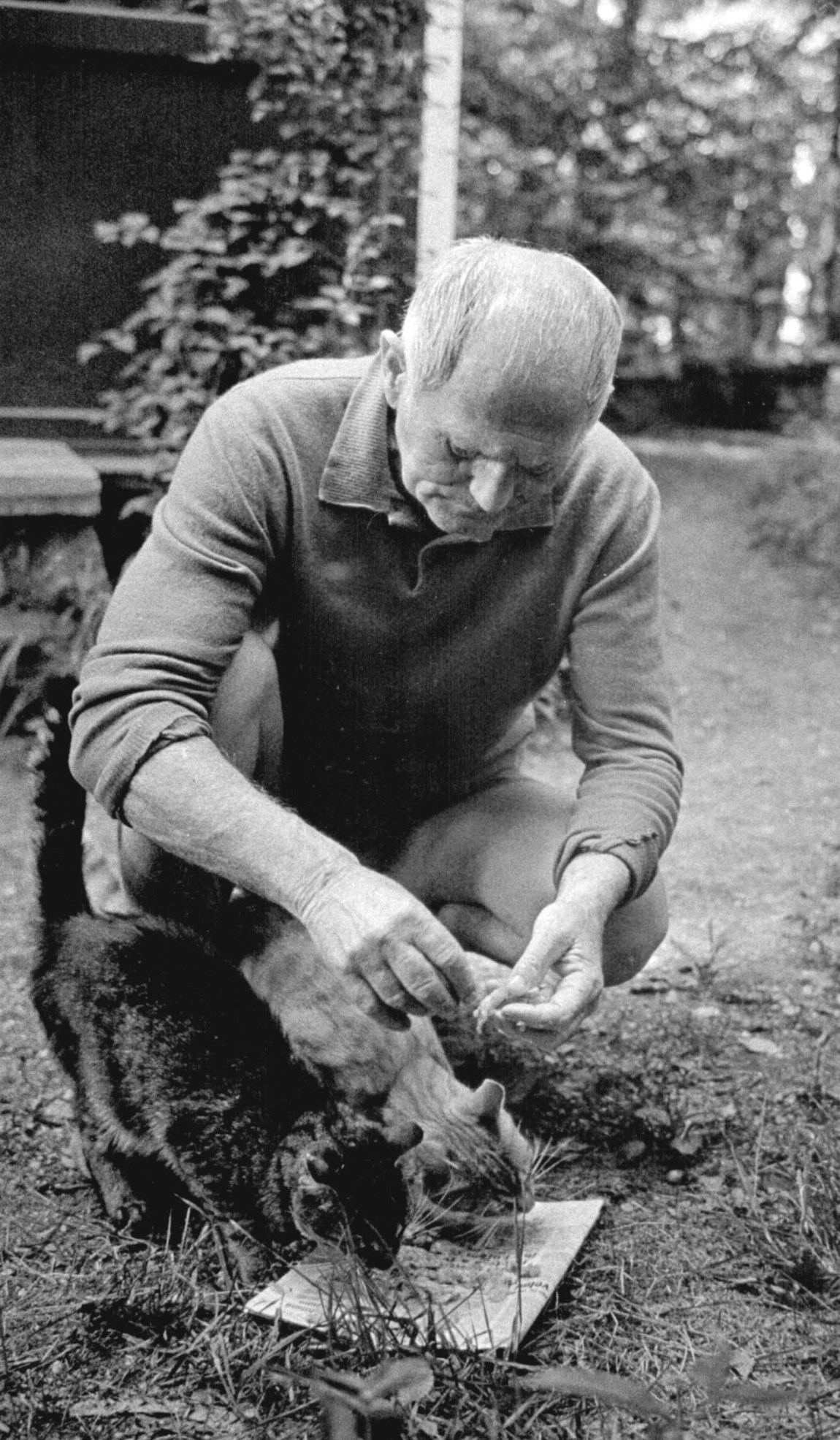

Tigger was my wife’s cat, found as a stray and passed on to her by a cousin when he was about a year and a half old. He lived with her in Boston, before we met, when she was working at a big law firm. On Sunday nights she would order in from an Italian restaurant and they would sit on the sofa and watch The Sopranos together. When my wife moved down to Virginia Tigger came with her, accommodating himself (after some initial friction) to my dog. In his youth he had had glorious golden fur, which became stringy and oily as he aged, owing in part to a thyroid condition. In his last years he suffered from dementia, sundowning as humans do. We grew used to finding him sitting in the exact center of the kitchen, yowling vigorously at no one. His death was devastating to us both; for days afterward we found ourselves bursting into tears without warning.

Cyrus came to us from a former colleague of my wife’s. He was a black cat and we often tripped over him on the dark linoleum in the kitchen. In his younger days he had been known to creep up on his first owner, the colleague’s future husband, and drop on him suddenly from above, like a feline version of Cato, Inspector Clouseau’s manservant. When someone in the family developed an allergy, we agreed to adopt Cyrus; my wife flew down with him from Boston to Richmond, an experience that terrified him. Before our daughter was born I took a lot of afternoon naps, and Cyrus used to join me on the bed, sleeping alongside me with his paw placed gently over my wrist.

His successor, Darwin, was passed on to us by a friend who was moving to New Orleans after a divorce. She had inherited him from her father, who had adopted him from a shelter. There he had been known as Ty and was regarded by the staff as “standoffish” (a claim we found hard to believe). Like Tigger he was an orange cat. Swaggering and imperious when we first knew him, he became increasingly stiff and frail in his old age. But he retained his love of chicken, and of sitting in cardboard boxes, and still enjoyed eating the dog’s food, in front of the dog, with his three remaining teeth. He died the summer before last while we were in New England; our cat-sitter arrived one morning and found him lying dead in a sunbeam, having suffered a stroke or heart attack overnight.

These creatures lived with us for years—in Tigger’s case, virtually his entire life. All were indoor cats, so their activities were on full view. Yet their inner lives remain an enigma to us. We loved them, but we do not know whether they loved us in the same way, or even liked us. We do not know how they conceived of us. As caregivers and protectors? As mobile can openers? As larger, less competent cats? We do not know what their thoughts were like at all.

Such ignorance is unsettling. It is more comforting to imagine that cats are pretty much like us: smaller, furrier humans. Vet techs are insistent that our cats regard us as parents. (“We’re going to give Mom some medication for you.”) Doting owners refer to their cats as “fur babies.” There is a long history of representing cats as quasi people. An Egyptian papyrus from the second millennium BC depicts a cat with a shepherd’s staff herding geese. Medieval manuscripts show cats playing musical instruments. The success of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Cats suggests an apparently boundless appetite for cats singing show tunes about their expertise in human professions (burglary, conjuring, piracy). There is a large market for cozy mystery novels with cat detectives.

Yet when the boundaries are blurred too far, we become uneasy. Stage productions of Cats merely gesture at felinity, with leotards, fur, and garish makeup. The result is campy, not frightening, except perhaps to small children. The 2019 film of the musical tried to make its all-star cast more catlike, using computer-generated imagery. The process stranded the actors in an uncanny valley, trapped between two species like the monstrous hybrids of Dr. Moreau. Audiences were creeped out and the movie flopped. We want to believe that cats are like us; we are uncomfortably aware that they are not.

This tension is integral to the art of Susan Herbert. Herbert, who died in 2014, spent her career working front-of-house jobs for the Royal Shakespeare Company, the English National Opera, and the Theatre Royal in Bath. A cat owner herself, she began at some point to depict cats in paintings. Her formula is straightforward: a famous work of art, with cats replacing the human figures. The Très Riches Heures of the Duke of Berry—but with cats. David’s The Death of Socrates—but with cats. Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe—with cats. A number of her paintings were collected in The Cats Gallery of Art in 1990, and other volumes followed, including Medieval Cats, Shakespeare Cats, Opera Cats, and Movie Cats. A compendium, Cats Galore, came out posthumously; Cats Galore Encore! now offers a second helping.

Advertisement

Herbert’s purpose, her sister tells us in the preface, was “to amuse and entertain,” and many of the paintings do no more. But some rise, perhaps accidentally, to real genius. The cat version of Vermeer’s The Milkmaid is a surrealist nightmare worthy of Max Ernst. The rendering of Van Gogh’s Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear is no less moving than the original. Often her versions bring out a latent felinity in the original. Once we have seen the cat in the human we cannot quite unsee it.

The Pre-Raphaelites offer Herbert some of her best material, perhaps because they are already poised on the thin line between art and kitsch. Her masterpiece in this mode is a version of William Holman Hunt’s The Awakening Conscience. An orange tomcat, in Victorian garb, paws at a tabby in a white dress who rises from his lap, her wide eyes fixed on something over the viewer’s shoulder. (The female model was Herbert’s own cat Polly, who figures in a number of her paintings.)

In Hunt’s original the protagonist is a fallen woman, seized with remorse at her own moral ruin. What is irresistibly comic here is the idea of a cat having a conscience to awaken, or feeling a call to higher things—higher, anyway, than the kitchen counter. We know, more or less, what Hunt’s ruined woman is supposed to be seeing, but what vision transfixes Herbert’s tabby? Birds out the window? A dangling ribbon? Dust?

In 1894 Thomas Edison’s studio produced a brief film of two cats boxing with each other. (The performers were supplied by a cat circus owned by one Henry Welton.) Important evidence of early motion pictures, this twenty-second movie has another claim to fame: it is arguably the first cute cat video. As technology advances, cats have continued to be early adoptees. Among the first YouTube videos still viewable is a thirty-second clip of a cat named Pajamas batting at a dangling toy while a song by Nick Drake plays in the background. It was uploaded within the site’s first month of operation in 2005, by someone known only as “steve.”

The mid-Aughts also saw the advent of LOLcats: viral images of cats with first-person captions, as featured on the website I Can Has Cheezburger? The site name illustrates the conceit underlying the meme: that cats can type but have not quite mastered grammar or spelling. Cats have since migrated with the rest of us to a series of new venues, including Facebook, Reddit, Instagram, and TikTok. Before I shuttered it, my own Twitter feed followed accounts called Cats of Yore (vintage cat pictures), Black Metal Cats (cats with baleful expressions), and “cats being weird little guys” (pretty much what it sounds like).

In The Internet Is for Cats, Jessica Maddox reports on a three-year research project ranging across various social media platforms. Maddox teaches media studies at the University of Alabama at Tuscaloosa, and she writes a dense academic English sometimes barely distinguishable from parody. (“The academic discipline of cute studies identifies how cuteness can be understood as both an affect and set of aesthetics….”) The objects of her Internet safari are duly problematized, theorized, and interrogated; we are shown, relentlessly, how things are “imbricated” in other things. But her book’s major claim is convincing: there is more to cat (and other animal) pics than meets the eye.

A popular New Yorker cartoon shows a dog at a computer console explaining to another dog that “on the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog.” But there are no real animals on the Internet. Dogs and cats have meaning on it, yes, but only at one remove, and only as a tool for human interaction. As Maddox points out, “Pets…do not post themselves.” The person who types “awww” or “sooo cute!” in response to a cat pic is not talking to the cat but to the person who posted the image, and to other commenters. In an attention economy, cats and other pets are cute capital. Adeptly deployed, their images produce clicks, likes, and follows. They form and maintain bonds between users. In a society shaped by the commodification of everything, they may even generate real money.

Some cats have become Internet celebrities. One is Tardar Sauce, better known as Grumpy Cat, whose adorably grouchy visage was purely accidental, the result of feline dwarfism and an underbite. Another feline star, Keyboard Cat, was recorded “playing” a jaunty tune, her paws manipulated by her owner from beneath a smock. Viewers began pairing the video with scenes of people falling down escalators or suffering other mishaps, often with the caption “Play him/her off, Keyboard Cat.” In late 2021 a cat named Jorts achieved fame in a Reddit post that went viral. A coworker of the poster had been spreading margarine on the cat’s coat, allegedly to encourage him to groom himself. For several days the phrase “buttered Jorts” was inescapable on social media.

Advertisement

As a survivor of workplace abuse, Jorts now tweets in support of organized labor. But some of his colleagues have embraced a more entrepreneurial outlook. Keyboard Cat appeared in a commercial for pistachios. Grumpy Cat endorsed Friskies brand cat food and Honey Nut Cheerios; Grumpy Cat merchandise included T-shirts, mugs, two books, a calendar, and a video game. Her death in 2019 ended her career as a spokesfeline, but not all celebrity cats have been so constrained. The original Keyboard Cat has had two replacements so far, with six lives presumably still to go.

Such success does not come without effort; Grumpy Cat’s owner left her job at Red Lobster to manage her cat’s career. But most people who post their pets are not so ambitious. They aim merely to give pleasure to others and to receive it in turn. As one of Maddox’s informants explains, pet pictures can serve as an antidote to doomscrolling: “Like, ‘here’s a list of all the people who died in Afghanistan this week, but also, here’s a French bulldog all tucked in for bed.’” “Having a rough day,” types the beleaguered office worker. “Send cat pics.” Strengthened by other people’s fur babies, we can dive once more into next year’s earnings projections or the departmental outcomes assessment document.

Should we see the joy experienced by the sharing of pet pics as an act of resistance, a small rebellion against a neoliberal economy? Or is it a palliative that keeps us from growing fractious and discontented, like the mindfulness programs so much in vogue with HR departments? Perhaps both, suggests Maddox. In any case, she cautions us against trying to sever the cute cat videos from the more toxic aspects of the Internet; the two are inextricably linked.

Despite her title, Maddox is not interested exclusively, or even especially, in cats. Cat pics for her are merely a subcategory (though a sizable one) of a larger class: pet pics or animal images. Yet there are real distinctions to be made here. The composer Ned Rorem claimed that everything in the world is either French or German. Isaiah Berlin divided thinkers into hedgehogs and foxes. Cats likewise form half of a binary system whose other half is constituted by dogs.

Cats are not dogs, of course, any more than night is day or a martini is a glass of milk. Dogs, as a class, are male, while all cats are female. Dogs are American, cats European (though in relation to each other Germans are dogs and the French are cats). Football is a dog sport (all that romping and mud). Cats are baseball players—meditative, motionless for long periods, then springing suddenly into action.

Cats are sensitive, precise, in love with nuance; dogs strive untidily for greatness. Some notable dogs: Picasso, Gladstone, Beethoven. Their cat counterparts: Klee, Disraeli, Ravel. Ezra Pound was a dog, T.S. Eliot—naturally—a cat. Tennyson was a cat too, while Robert Browning was a dog—a great, furry Newfoundland bounding into the house after a walk and shaking water all over everything, including his wife’s indignant spaniel, Flush. Hemingway posed as a dog, to himself as well as others. But it was a cat who wrote The Sun Also Rises and “Hills Like White Elephants.”

That dog should be the opposite of cat is neither natural nor universal. The Greeks and Romans were familiar enough with cats (though much of their mousing was done by snakes and weasels). But cats play almost no role in the Greco-Roman imagination. And Greek dogs, lacking an opposite number, have quite a different significance, being associated not with loyalty or honesty but with faithlessness, servility, and women.

For us, though, the divide is absolute. Dogs embody our love of the world, in all its richness and variety. Cats represent the world’s indifference to us. Dogs want to please us; they come when called. Cats may recognize their names but see no need to answer to them. And why should they? Cats don’t care.

“Why can’t a cat be taught to retrieve?” asked Wittgenstein in one of his Zettel. “Doesn’t it understand what one wants? And what constitutes understanding or failure to understand here?” He is not the only thinker to have been intrigued by cats’ implacable otherness. In Feline Philosophy John Gray looks at various concepts—happiness, virtue, love, death, the meaning of life—and subjects them to a simple test: Would our preoccupation with these things make any sense to a cat?

The answer, mostly, is no. Rejecting ideas of moral goodness that go back to the Greeks, Gray throws in his lot with the Taoist concept of te (“acting as you must”) and Spinoza’s idea of conatus (“the tendency of living things to preserve and enhance their activity in the world”). By these definitions, to live a good life is not to achieve (moral) virtue but to realize one’s particular nature.

Gray uses several real cats as touchstones. One is a Siamese named Mèo. Adopted as a hungry, flea-ridden kitten during the Vietnam War by an American journalist, he lived in the Da Nang press compound, a Saigon hotel, a house in Connecticut, a Manhattan brownstone, and a flat in London. He survived being hit by a car and coming down with pneumonia, as well as six months of British quarantine: “Throughout the smoke and wind of history, Mèo lived his fierce, joyous life. Torn from his home by human madness, he flourished wherever he found himself.” It is this flourishing—flourishing as a cat—that for Gray constitutes Mèo’s success.

Mèo, like all cats, had no moral sense. Cats aren’t preoccupied with being good, only with being cats. They are incapable of empathy, altruism, pity, or kindness, and likewise incapable of cruelty or sadism. They are beyond good and evil. Cats don’t know that they will die, though they may sense the approach of death when it comes. They do not search for meaning in their lives.

Cats refute continuously the claim that the unexamined life is not worth living, by living it. They are both Stoics and Epicureans: they live in accordance with nature and they seek to maximize pleasure. But they do this without reading treatises or attending lectures. Nor do they share the defensive outlook and rejection of the world common to both schools. That cats have no use for philosophy is an indictment, for Gray, not of cats, but of philosophy: “Posing as a cure, philosophy is a symptom of the disorder it pretends to remedy.”

If cats have the answer—that there is no answer, for there is no question—it follows that the best philosophers will be the most catlike. A cautionary example here is Pascal, who lived an anxious life trying to overcome his dread of death through faith and reason. Not a cat person, Pascal. Gray’s sympathies lie rather with Montaigne and Samuel Johnson, who recognize the futility of human striving and urge us to take life as it comes. Not surprisingly, both were cat owners.

Gray’s chapter on cats and love begins with some fictional cats in works by Colette, Patricia Highsmith, and the Japanese novelist Junichiro Tanizaki. All three writers present the relationship between man and cat as a complete and satisfying one, in contrast with the messes people make of their involvement with other humans. “In love, more than anywhere else,” says Gray, “human beings are ruled by self-deception. When cats love, on the other hand, it is not in order to fool themselves.”

A real-life story along these lines involves Gattino, chronicled by Mary Gaitskill in her essay “Lost Cat.” Gaitskill adopted Gattino as a skinny kitten in Italy and brought him back to the US. There, not long after arrival, he went missing. Gaitskill hunted for Gattino, put up posters, and even consulted psychics. On several occasions she felt she was receiving mental messages from him: “I’m scared”; “I’m lonely.” There was a possible sighting at a nearby university, but the search came up empty. Gattino was never found, and it seems likely that he fell victim to a bobcat or coyote. His last message to Gaitskill was as simple as his earlier ones: “I’m dying. Goodbye.”

This is, one might have thought, a sad story. But Gray thinks otherwise. Gattino’s life was short, but it “was not sad in the way human lives can be sad.” His end may have been gruesome, but he and Gaitskill enjoyed a pure and uncomplicated love, one that contrasted strikingly with the troubled relationship Gaitskill had with her father.

Gray clearly wants to see Gattino’s life as meaningful. Gattino, he insists, “was not a loser.” But if Gattino’s life had meaning, it seems to have been primarily for Gaitskill (and Gray). Like Maddox’s, Gray’s book is, in the end, about humans. The cats he discusses, real or fictional, are vehicles for us to think about ourselves. Cats themselves have no philosophy, feline or otherwise. They’re just cats.

Cats have often made good companions for intellectuals—“amis de la science,” Baudelaire called them in “Les Chats.” The Latin textual critic D.R. Shackleton Bailey dedicated his seven-volume edition of Cicero’s Letters to Atticus to his white cat, Donum, whom he called “more intelligent than most people I have encountered.” (Feline Philology is a book that remains to be written.) But the relationship has not always been a happy one. Descartes once threw a cat out a window to satisfy himself that animals lacked consciousness.

Gray also tells us of the nineteenth-century neurologist Paolo Mantegazza, who studied the physiology of pain by torturing cats in a device he called “the tormentor.” When not abusing animals, Mantegazza was a futuristic novelist, a scientific racist, a cocaine enthusiast, and a progressive deputy in the Italian parliament. But animal cruelty bridges partisan divides. As a Harvard medical student, the future Republican Senate majority leader Bill Frist adopted cats from Boston-area animal shelters, whisked them off to the lab, and dissected them, to provide data for experiments on cardiac muscles. He had the grace to express some regret about this later.

Man’s inhumanity to cats is a central theme of the Czech writer Bohumil Hrabal’s brief memoir Autíčko, first published in 1986 and now translated into English as All My Cats. Hrabal was long known to English readers (if at all) as the author of Closely Watched Trains, the basis for the 1966 film by Jiří Menzel. But recent years have seen a flurry of new or newly republished translations, including I Served the King of England, Dancing Lessons for the Advanced in Age, and The Gentle Barbarian.

Like Susan Herbert, Hrabal found his form and stuck with it. In a typical Hrabal novel, a speaker of low or marginal social status retails, in a sprawling monologue, memories of a picaresque career. The content is often bawdy, the tone generally comic. Hrabal referred to this trademark style as pábení—rambling or palavering.

All My Cats is recognizably pábení, but with some differences. For one thing, the palaverist is Hrabal himself. The book also lacks the nostalgic, happy-go-lucky tone of other Hrabalian productions. Brief as it is, it makes for grim reading.

The action takes place at the Hrabals’ weekend house at Kersko, an hour’s drive from Prague (though Hrabal often takes the bus). At the beginning of the book the property is home to five cats. During the week they fend for themselves; on weekends the Hrabals arrive to feed them. The weekly reunion is joyful, but each return to Prague fills Hrabal with guilt:

In every available chink in the fence there would be a cat’s head poking out, five little cats’ heads in all, following my departure and longing for what could not be altered, longing for me to return so we could all be together in the snug little room by the warm stove.

The cat population fluctuates. One of the tomcats, Renda, is adopted by a stranger, a woman from the city who arrives one day and carries him off before Hrabal can protest. The woman’s son returns the cat some months later in an emaciated state; unhappy in his new situation, he has stopped eating.

A pregnant tabby shows up and has kittens. So does Blackie, Hrabal’s favorite of the original quintet. “What are we going to do with all those cats?” asks Hrabal’s wife in desperation. Eventually Hrabal kills six of the ten kittens, putting them in a mailbag and beating them to death. The killing weighs on his mind, though the two mothers seem unperturbed by the disappearance of their offspring; indeed, they treat Hrabal with even more affection. Then Blackie comes down with a fever. Hrabal holds her down as she writhes and spits, and finds he has broken her neck.

Renda the tomcat vanishes for good sometime after his return, perhaps hit by a car or killed by hunters. He appears to Hrabal in early morning visions and reproaches him. Another tabby appears and has two kittens. One is adopted by a woman in Prague. The Hrabals keep the other, naming her Autíčko (little car) after their Renault.

Then Autíčko becomes pregnant. So does her mother, again. (At no point does it seem to have occurred to anyone to have the cats spayed.) Now there are ten more kittens and once more the refrain: “What are we going to do with all those cats?” Five, happily, are adopted by various neighbors. The two mothers quarrel with each other and reconcile, but then turn their aggression on their own offspring and on Hrabal. When both become pregnant yet again, it is time, once more, to bring out the mailbag.

Hrabal feels the weight of his murders ever more keenly. He visits a faith healer but finds no comfort. An encounter with a disturbed neighbor opens his eyes to the cats’ slaughter of songbirds, but the relief is short-lived. Then Hrabal and his wife are nearly killed in a car accident, an experience that he mysteriously interprets as absolution for his sins. He returns, redeemed, to the three remaining tomcats, whose offspring will be someone else’s problem.

To call Hrabal a cat lover feels actively misdescriptive—like referring to William S. Burroughs as a recreational drug user. On Hrabal’s side, at least, the relationship seems almost entirely toxic. The cats represent for him an enormous burden of responsibility, anxiety, and guilt. At one point he compares his murder of the two pregnant cats to the 1950 execution of the Czech politician Milada Horáková by the Communist regime “merely because she had opinions that were deemed unsuitable.” The comparison seems far-fetched—bizarre, even. Yet as the book proceeds, the killing of the cats is asked to carry even heavier symbolic weight:

It was as if I had lived through all those wars, as if I had taken part in the massacre at My Lai, the massacre in Lebanon, as if I had been through everything I read about in a book called A Century of War Photography.

The final item undercuts the hyperbole without quite deactivating it. Hrabal ironically calls himself “the king of Czech comedians,” but the comedy here is bleak indeed.

That Hrabal’s cats have some larger meaning seems clear, but it is harder to say what that meaning is. If pressed, I might say that they represent the world: our efforts as humans to cope with it, the claims it makes upon us, the violence we find ourselves visiting upon it merely by living in it. But perhaps the point is rather our own grandiose need, as humans, to impose a false significance on the world. The cats, after all, are just cats.

One of the chapters in Hugh Kenner’s The Pound Era analyzes a short poem by William Carlos Williams:

As the cat

climbed over

the top ofthe jamcloset

first the right

forefootcarefully

then the hind

stepped downinto the pit of

the empty

flowerpot

As Kenner showed, the poem’s effect relies on syntactic suspension. “As” in line 1 opens a door that is not shut until the final word. Our inkling that “forefoot” in the sixth line might be the subject is not confirmed until the eighth. Nothing in what precedes allows us to anticipate the final “flowerpot.” But if we cannot predict at any given moment what word will come next, that is our problem. The sentence, like the cat, knows exactly where it’s going. As Kenner writes, “We can no more imagine what it is like to be a cat than we can imagine what it is like to be a sentence.”

The best descriptions of cats show this blend of mystery and attention. In the year 889 the Japanese emperor Uda described the cat given him by his imperial predecessor:

My cat is a foot and a half in length and about six inches in height. When he curls up he is very small, looking like a black millet berry… The pupils of his eyes sparkle, dazzlingly bright like shiny needles flashing with light, while the points of his ears stick straight up, unwaveringly, looking like the bowl of a spoon.

(translated by Judith N. Rabinovitch and Akira Minegishi)

There is fancy here, but also an exactness of observation that Williams would have recognized. It is with a similar mix of precision and wonder that the eighteenth-century English poet Christopher Smart considers his cat Jeoffry:

For then he leaps up to catch the musk, which is the blessing of God upon his prayer.

For he rolls upon prank to work it in.

For having done duty and received blessing he begins to consider himself.

For this he performs in ten degrees….

Some of the terms Smart uses are puzzling: “musk,” “prank.” The former may be a geranium or a kind of fruit; “upon prank” means playfully. But even their obscurity inadvertently adds to the effect—words of a cat language, perhaps, in which we are still unpracticed.

Smart’s lines come from his fragmentary poem Jubilate Agno (Rejoice in the Lamb), which the poet wrote in an asylum. After a seizure of some sort in 1755, he had begun praying loudly in public and demanding that others join him. He was eventually committed to a series of institutions—though never, mercifully, to Bedlam itself. We know nothing of Jeoffry beyond the seventy-four lines that Smart devotes to him.

Undaunted by this lack of information, Oliver Soden has now written Jeoffry’s biography. His acknowledged model is Flush, Virginia Woolf’s life of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s cocker spaniel. In his narrative we follow Jeoffry from his birth in the cupboard of a Covent Garden bordello to his years with Smart, first in the asylum and then in hired lodgings, and finally to a sedate old age with a widow in Devon.

The perils of such an undertaking are many. The potential for cringe is always present, yet the book is never cutesy or twee. One might fear that the pet’s biography will be merely an excuse to write about its owner. And we do learn a certain amount about Smart; Soden at one point apologizes for putting Jeoffry aside “just for a page or two” to introduce “a major supporting player.” But he gives full measure to his actual protagonist.

Some famous figures make cameo appearances, always from a cat’s-eye view: David Garrick appears as a green-gloved hand attached to a “rich and resonant” voice, the elderly Handel as “two milky eyes…, vague and unseeing beneath a large and trembling wig.” Dr. Johnson visits his friend Smart in the asylum (“I’d as lief pray with Kit Smart as anyone else,” Boswell records him saying), and Jeoffry later has a brief but memorable meeting with Johnson’s cat Hodge. Alas, our hero was born too late to encounter Horace Walpole’s tabby Selima, who drowned in a goldfish bowl and was mourned in a poem by Thomas Gray. In compensation, Soden lets Jeoffry live to a ripe old age. He survives Smart by several years, long enough to be petted at vaguely by the infant Coleridge.

Unsurprisingly, the years with Smart are the heart of the book. The asylum period is an imprisonment for Jeoffry too. Used to the sounds and smells of London, he is now confined by a wire-topped wall to Smart’s room and tiny garden. We watch with him as Smart is force-fed his “medicine” and herded out naked into the rain with other patients, in lieu of bathing. Soden movingly imagines Smart’s mental illness as experienced by Jeoffry:

To Jeoffry, the man smelled of fear…. Around Smart stretched something that was not there, but which Jeoffry could see all the same: an absence of light, like a silk blanket that was not black but blank, that was not dark but vacuous, empty of meaning, devoid of sense…. On some days the blanket and its jabs sent Smart mad, and on other days it sent him still, and sometimes Jeoffry could see that it wasn’t there at all. Jeoffry knew it for what it was, but what it was he could not say.

Whether this catches a cat’s experience, who can know? But at least it takes seriously the gulf between cats and ourselves.

Even attuned observers cannot resist attributing human behavior to cats, if only playfully. Smart believed Jeoffry to be “the servant of the living God duly and daily serving him” after his feline fashion. Emperor Uda notes that his cat has a preference for Taoist-style health practices and “instinctively follows the ‘five-bird’ regimen.” Joyce’s Leopold Bloom idly wonders whether cats keep kosher.

In the end, though, we are better off asking nothing of cats but that they be cats. In the ninth century an anonymous Irish scholar observes his pet, Pangur Ban, hunting mice while his master toils over a manuscript:

So in peace our tasks we ply

Pangur Ban, my cat, and I;

In our arts we find our bliss,

I have mine and he has his.

(translated by Robin Flower)

And sometimes, if we are respectful and attentive, we may be rewarded with real communion. Emperor Uda records one such moment:

I once said to the cat, “You possess the forces of yin and yang and have a body that is the way it should be. I suspect that in your heart you may even know all about me!” The cat heaved a sigh, raised his head, and stared fixedly at my face, seeming so choked with emotion, his heart so full of feeling, that he could not say a thing in reply.

Uda abdicated in 897, after a ten-year reign, in favor of his eldest son, and spent the last three decades of his life as a Buddhist priest. What became of the cat we do not know.

This Issue

June 22, 2023

Fireball Over Siberia

Who Are the Taliban Now?