Nick Drnaso draws comics with a minimalism just this side of crudeness. The colors are flat, the lines uniform and thin, the pages strict grids of small panels. His characters are soft and boxy and barely differentiated, like cheap cars: their clothes are vague masses of fabric, their hair sits in rigid lumps above round, empty faces—in his first two books, the collection of linked stories Beverly (2016) and the graphic novel Sabrina (2018), their eyes are simply black dots. These faces are at times capable of registering subtle and powerful emotions—both books focus on the aftermath of shocking, violent events—but more often they are almost blank, barely animate. Drnaso’s people seem to be staring out from somewhere deep within their own amorphous bodies, imprisoned and perplexed.*

In his new graphic novel, Acting Class, this changes, just a bit. The layouts are a little looser, there’s more surface detail on hair and clothes, more contour to people’s forms; their eyes now have pupils and color. Acting Class has a larger cast of characters than his previous books, and Drnaso has said that this required showing “a wider variety of distinguishing details”—but the result goes far beyond that purpose. It is startling how even the most minute shift in drawing style can affect the tone of a comic. The whole book feels a few degrees warmer, more humane, quieter, yet somehow more uncanny. His people still look a bit stunned by their own existence, but one can imagine them thinking and feeling, rather than just reacting or failing to react.

In the book’s opening pages ten people gather for a free acting class, held at a community center once a week after hours, attracted by a flyer or word of mouth and, as the teacher tells them, “because something is wrong in your life.” They bristle at this, and at his explanation that he just means they are “restless searchers,” but he is, by and large, right: the students include a bored married couple, a stressed-out single mother, an unstable young woman and her protective grandmother, and an assortment of awkward loners. And if one or two don’t quite seem to fit his description, he soon makes sure they do.

Iris Murdoch often spoke and wrote about “the way in which people make other people play the role for them of gods and demons,” as she put it in an interview in the late Sixties, and how charismatic “enchanter” figures could “come in and generate [such] situations,” since “there are always victims ready to come forward.” In this sense, Acting Class is a thoroughly Murdochian book. The enchanter at its center tells his students he has been “a teacher in one form or another for over thirty-five years,” that his name is John Smith—“a name that’s easy to forget”—and very little else. He is an easygoing, relentlessly positive man in late middle age, nondescript apart from his crooked teeth and unnervingly vibrant blue eyes. (One almost suspects Drnaso started drawing irises purely to include this detail.) Like his name, his speech and manner are almost ostentatiously generic. The very lack of distinguishing features seems to pull people toward him.

His class involves no lessons in technique, no scripted performance, little critique or feedback. Instead, he puts his students through a series of improvised scenes, with the most minimal of prompts: two of them are to act as a boss and an employee, say, and “the rest is up to both of you.” It soon becomes clear that the goal is not to improve anyone’s ability to perform or mimic, but to cajole them into entering an imagined world and unmoor them from their current lives.

Drnaso renders these shared fantasies with a matter-of-factness that makes them strangely engrossing. As the characters enter their fictional personas, the backgrounds shift with them—the blue and gray of the community center basement is replaced, a panel later, by the drab browns of a manager’s office or a suburban home; a metal folding chair becomes an imposing desk chair, and then reverts as the improvisers lose the thread. The ordinariness of the transformation makes clear that the spell John Smith is weaving owes less to the content of these shared hallucinations than to the simple fact that they are not real life.

The core of the book consists of several long sequences of this improvisation, often involving the entire class, over the weeks that follow. In the first, John tells them that they are all at a party and gives them each a line or two to guide their character. Over fifteen densely packed pages, we watch them make inane small talk, play games, have revealing conversations, move in and out of the party, in and out of the fantasy.

Advertisement

John’s prompts often seem more like psychological interventions than acting guides. During the party scene, for instance, he tells Dennis, a tedious, clinging husband, that he’s immediately enamored of his classmate Angel—and tells Rosie, Dennis’s bored wife, that she’s intensely attracted to Rayanne, another classmate. To Angel, a young woman whom we first meet failing so thoroughly to read social cues that she stays at a dinner party until four in the morning, he says: “You can’t be pinned down. You have an authority problem…. You move freely and often to avoid responsibility and attachment.” In the book’s opening pages, we saw Lou, a muscle-bound loner, bringing a plate of cookies to his coworkers. No one eats any—“I’m not saying anything,” one coworker remarks to another. “I just think you should try one first.” Now John tells Lou to be another character’s dog: “Is it any different than playing a lawyer or a security guard?… You’ll be great.”

Nothing particularly dramatic happens, but the scene is fascinating: an ordinary, boring situation subtly but thoroughly deranged. Every minor, seemingly simple interaction needs to be interpreted—Is this intentional performance? Unintentional revelation? A rejection of the situation or an embrace of it?—as a mundane yet unreal world is molded and negotiated, moment by moment, in front of us.

As the classes proceed, these exercises begin to have powerful effects on many of the participants. Lou pursues his canine character for the rest of the book; we later get a brief glimpse of him lying in bed, growling and barking to himself. Angel is so consumed by her “‘rebel without a cause’ persona” that she enters a fugue state, in which the character takes over the rest of her life. Drnaso draws this altered reality as a kind of hackneyed Pottersville, all neon lights and new friends made in bars, but it has very real consequences: Angel abandons her job, her apartment, and her cat and, in the moments when her real personality reemerges, has no memory of what she’s been doing or even where she’s been.

Those are the most extreme cases, but for all John’s students a psychic porousness seems to develop. The classes set something loose in them, and it isn’t always clear how much of it stems from John’s suggestions and how much was already there beneath the surface. Rosie and Rayanne’s mutual attraction also continues for the rest of the book; it makes plenty of sense on its own—they both feel hemmed in by their domestic lives, and their rapport seems easy and genuine—but would any of it have happened without John’s prompt? Did he create their feelings, or detect their beginnings and help them emerge?

Thomas is the most outwardly self-confident of the students, a friendly young man who works as a nude model for drawing classes at a local community college and wears his hair in a ponytail—quite a flashy choice in the thoroughly muted world Drnaso has created. For the party scene, John takes him aside and tells him, “You are a liar and thief…. You have to act on these impulses and not get caught.” He is, in fact, caught—going through the pockets of the very real coats belonging to his classmates. “It’s part of the performance, I’m just acting,” he explains. “I’m sorry.” “Why are you apologizing,” his classmate asks, “if it’s just a performance?”

In an interview with the comics magazine Bubbles, Drnaso said that this was John, “for his own reasons,” manipulating and gaslighting Thomas, attempting to “break him down.” But as Thomas’s self-confidence falters over the course of the book, and his acting exercises become filled with fear and shame and nebulous violence, it seems less simple than that. Was he really so confident in the first place? If so, why did it take such a tiny push to make him fall?

In a later class—held in a house in the woods a long drive out of town, as if to test the students’ commitment—John gives them an exercise that abandons the concept of “performance” entirely. “You’re all going on a solo journey,” he announces, and asks them to lie down. “Create a scene in your mind as completely as possible. Put yourself in the scenario, arrange some elements, and see what happens.”

What follows is an extraordinary succession of reveries, each a dense layering of the students’ explicit and implicit desires, their memories and anxieties, along with the ongoing influence of John, clearly present yet hard to pin down. Rayanne imagines her three-year-old son as a hideous green monster, relentlessly growing, already too big to get through the door of his room—and invites an imaginary Rosie over to help. Rosie, meanwhile, imagines her husband intruding uninvited into her own exercise. When she tries and fails to imagine herself leaving the scene and going to Rayanne, he tells her it’s because “your heart’s not in this…. You have to listen to John. You have to give yourself over to the process.”

Advertisement

Lou imagines an idyllic life as someone’s pet, then that he is being led to a slaughterhouse—still as a dog—and made into food to be consumed by his owner. Thomas imagines himself trapped in a Kafkaesque interrogation, accused of kidnapping a local disabled man and of incriminating himself at the acting class. “This isn’t acting,” a policewoman chides him. “This is real life.”

Drnaso carefully avoids all the flashier possibilities of the comics form. There are no elaborate panel arrangements, no exaggerated physiognomies or wild artistic flights. Even his monsters are a little stiff and recessive. But his pacing—panel to panel, page to page—is subtle and powerful, precisely controlled; these scenes feel endless, dreamlike, and yet go by quite quickly. His tone is relentlessly ambiguous: the book never tips over into horror or satire, always remains slippery, unsettled.

All of Drnaso’s books share a sense that the world their characters are living in is flimsy, inadequate—that it could pop like a balloon at any moment and leave just a few sad scraps behind. In his previous work, that rupture came from without, in the form of murders, fatal accidents, and violent intrusive thoughts; the world was terrifyingly fragile. In Acting Class, by contrast, violence and exploitation lurk only at the far edges of the story. The characters don’t fear the dissolution of their world; they long for it. That is what gives John his power: he knows this before they do. “You would like to see a new dimension,” he tells them all early on, in his blandly seductive way, and they do.

In the end, John does have a larger purpose behind it all—as most readers will have long suspected. “I’m just a recruiter,” he declares at the end of the class’s final and most elaborate exercise. He invites his students into vans, which will take them to the “larger group…where the real work happens.” The class is “no longer free, but we’ll work something out.”

Many of them go, a few don’t, though no one, it seems, escapes without consequence. It is, on one level, an obvious betrayal, in which the book is revealed to be an examination of the psychological dynamics of cults—the long process of breaking down and building up, exploration and manipulation, recruitment and isolation.

But Drnaso does not let it sit so easily. He gives no sense of what this larger organization is, and does nothing to make it feel malevolent or even particularly real. It seems as much the abstract idea of liberation as an actual group, and those who choose it at the end of the book seem bound as plausibly for nirvana as for NXIVM. Drnaso’s subject is not the “next phase of the class” John offers but the deep, powerful feeling that makes that offer so tempting—the longing to change your life, and what you can learn, and lose, by pursuing it.

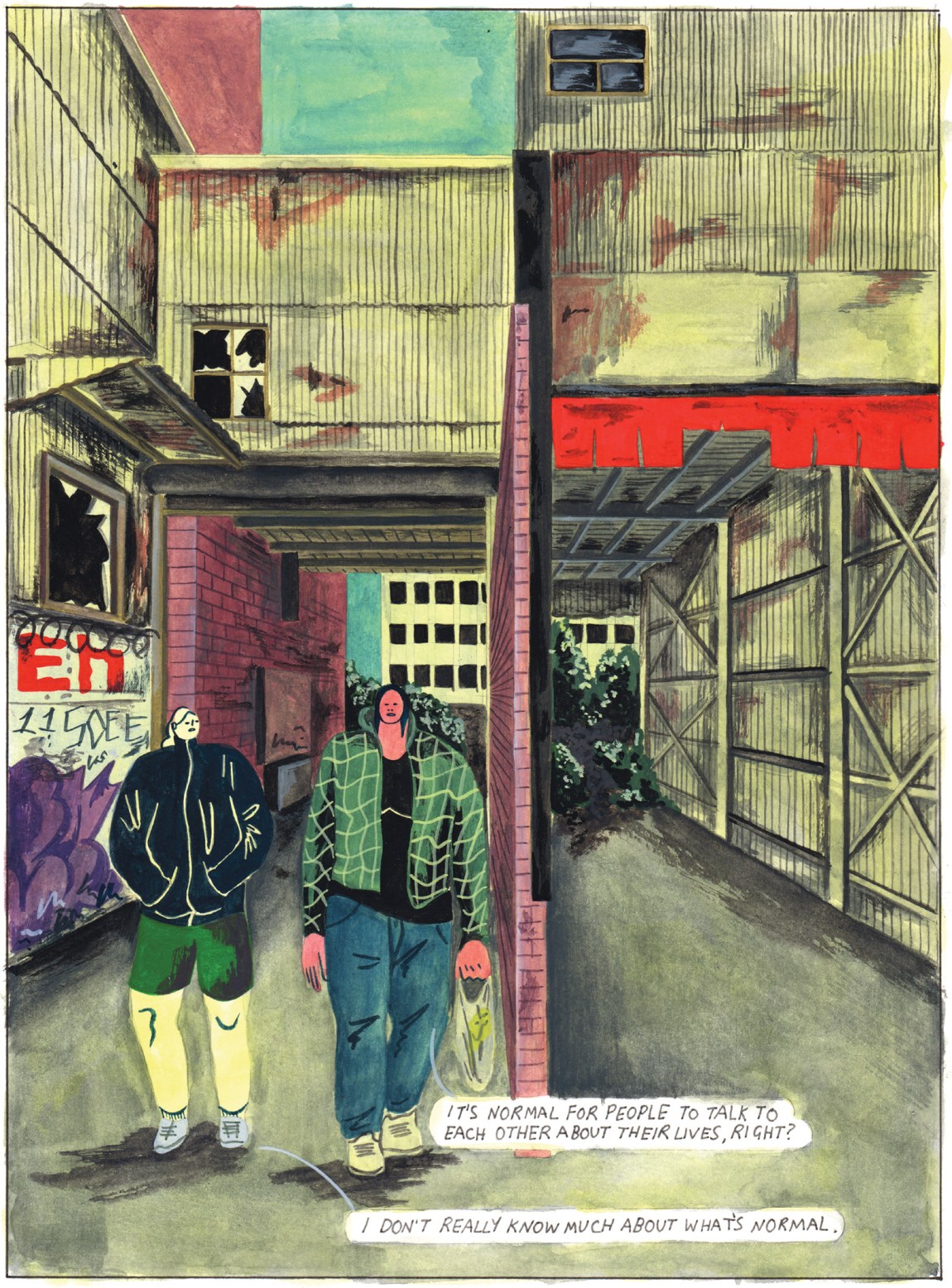

Tommi Parrish’s new graphic novel, Men I Trust, takes that same longing as a starting place. (I don’t think it’s a coincidence that both Parrish and Drnaso are in their early thirties, both with a couple of other books behind them—just the point when one might begin to take stock, and to wonder.) But where Drnaso lingers in the desire for change, dissecting it, spinning off complications and contradictions, Parrish focuses on the hard work of actually making change happen. It’s a book about the reality of trying, day by day, to be a better version of yourself.

Parrish’s characters often find themselves struggling to put their feelings into words, but their bodies are always wildly expressive. Parrish’s approach to the human form—or “THIS CLUNKY COSTUME OF FLESH AND NERVES,” as they put it in one short comic (Parrish uses they/them pronouns)—is the most distinctive aspect of their art. The characters’ faces are consistently deemphasized, the heads disproportionately small and the features drawn with just a few quick lines or even omitted entirely. The rest of the body is outsized, bulbous, more than a little elastic: jutting elbows, huge, expressive hands, vast swaths of torso and leg. Parrish’s bodies dominate the room (and the page), and yet their sheer expanse seems to accentuate their vulnerability as much as their power. They are inescapable, and inescapably exposed.

At the center of Men I Trust is a brand new friendship, wobbly and fragile and exciting, between two women at different stages in the process of changing their lives. Eliza is a thirty-two-year-old single mother, a recovering alcoholic, and, whenever she can find the time and energy, a poet. Sasha seems much younger but is twenty-nine (“Wait…really?!” says Eliza); she has just moved back in with her parents after an unspecified crisis, and does some sex work now and then. They meet after one of Eliza’s readings. The words she reads are a “thinly veiled metaphor for depression,” as Parrish’s narration puts it (and in reality they’re drawn from a poem by Anne Boyer, “What Resembles the Grave But Isn’t”), yet Eliza delivers them with an energy and physicality—rendered in a page of fifteen vibrant, densely packed panels as she emotes and gesticulates, addressing the mic from all sorts of angles—that make them feel urgent and alive.

Sasha is immediately smitten. She introduces herself, meets Eliza’s young son, Justin, helps them schlep their stuff home, lights a fire in a gutter to amuse them, yells at a reckless motorist on their behalf. The conversation is halting, inarticulate. Sasha is voluble and scattered. “Your writing’s just so, like—” she declares, then resorts to sticking out her tongue and slicing an imaginary knife across her belly. Eliza is clearly tired, and doesn’t quite catch Sasha’s name at first, but seems charmed by her enthusiasm.

After Justin is put to bed, they sit together drinking tea. Eliza is, for Sasha, an “inspiring” version of what she could become—someone creative and unconventional but capable of maintaining an adult existence with real responsibilities. “I just think it’s really cool, you know,” she says, “what you’ve built, the life you’ve built.” Eliza, for her part, sees an earlier version of herself in Sasha, someone still prone to declaring that “most of my energy goes into trying to not want to die!” Perhaps, too, she sees a reminder not to let her fatigue and determination turn into callousness—Sasha represents a self she does not want to leave completely behind. As the evening winds down, Sasha goes in for a kiss but is gently, awkwardly rebuffed.

This kind of spiraling, intimate, unresolved encounter between two people has become Parrish’s signature form. Most of their shorter works—many of which were collected in Perfect Hair (2016)—are similarly open-ended duets: a sex worker and client pretending to be in love (“Young Spirits Scene”); friends trying to reconnect (“Sufficient Lucidity”); a “Generic Love Story” starring two naked, abstract figures. Their first graphic novel, the fantastic The Lie and How We Told It (2018), takes place over a single long evening as two former friends, Cleary and Tim, run into each other in the supermarket and then catch up over drinks.

Tim almost immediately announces that he’s become engaged to a woman but, as he drinks more and more heavily, keeps steering the conversation back to his sexual encounters with men. Cleary, who is queer, reminisces about the closet (“It was all such a fucking mess”) but struggles to respond to Tim’s aggressive bonhomie and obvious panic. The conversation lurches and sputters, circling around sexuality and denial, need and delusion, the way a friendship can go from being “my whole world,” as Cleary puts it, to this strained dance between near strangers. But they never quite figure out how to talk to each other. Tim weeps, briefly, in the men’s room. Cleary explains what a “weird night” it’s been to an attractive bartender. In the end, they just go their separate ways.

Parrish has said that they try to avoid “unnecessarily gendering” characters when drawing them. Everyone is “shaped like a person,” and the rest is often left ambiguous until signaled by a name, a pronoun, or a choice of clothing. (When Sasha puts on a skimpy outfit for a date with a client, it is clearly a costume, or even a uniform, with little relation to the body within.) In description this might sound a bit didactic, but in practice it is so natural it is almost invisible; only gradually does it dawn on you how different these depictions are from those in most other comics, with their unmistakable, unchanging breasts and lips and waists and biceps. Parrish’s books simply take for granted that gender is something the characters perform—or don’t—from moment to moment.

Their drawings also generally highlight body language instead of the subtleties of facial expression. In the space of three panels, a character might splay a hand out in greeting, dip it down to emphasize embarrassment, cock it on a hip to admire an outfit. The page near the end of The Lie and How We Told It in which Cleary and Tim say good-bye to each other is a small masterpiece of social choreography, hilarious and devastating: one goes in for a hug while the other reaches for a handshake, they both tighten up in chagrin, they try and fail again, this time in reverse, then finally manage an oddly tender left-handed clasp.

Conversation in Parrish’s work is a ragged improvisation, both inadequate and highly significant. Their comics are full of Uhs and Ohs and Haha reallys, lulls and evasions and false starts, the fleeting aggressions and misunderstandings of people trying to connect—and the joy and terror when something real does manage to break through. Early on in Men I Trust, Eliza, reaching for some way to help Sasha, tells her to try “the gratitude game”: “Basically you just write down everything you’re grateful for every night before you go to bed…. It can help with breaking up negative thinking.” Much later in the book, when Eliza vents to Sasha about her own life—“Being broke is almost as exhausting as it is humiliating”—Sasha responds, “Have you—I don’t know. Have you tried counting the things you’re grateful for?” It’s snide and callous (and she immediately apologizes), but in between these scenes we’ve seen that Sasha did, in fact, sincerely try to play the game, however platitudinous it seemed. Can hostility express gratitude? Are sympathy and condescension sometimes the same thing?

In many of Parrish’s earlier comics, their interest in duets went along with experiments in formal bifurcation. They played with a disjunction between image and narration, or a division into “before” and “after.” Tim and Cleary’s encounter, for example, is repeatedly interrupted by a story within a story, a comic book called One Step Inside Doesn’t Mean You Understand that Cleary (in a conceit somewhere between clunky and charming) finds in a bush. Parrish uses a minimalist, black-and-white style quite different from the rest of the book, with no speech balloons and just a single large panel per spread—it’s even printed on a different paper stock—but it too is a pas de deux. Its icy narration describes a brief, unsatisfying relationship between a stripper and a wealthy older man. “He’s as colorless as the sex,” she reflects as it ends. “My disgust has passed through rage and emerged as a militant indifference.”

Men I Trust replaces this kind of formal gambit with greater narrative complexity and an intense attention to the texture of the images. The relationship between Sasha and Eliza unfolds in a series of encounters, rising in intimacy and intensity before suddenly falling apart. But the scenes between them are broken up by other pairings and occasional larger groups: Eliza and her son, as she struggles not to give in to her weariness and frustration in front of him (or tearfully apologizes after she does); Sasha and her mother, who is reflexively critical, often a bit drunk, but also genuinely worried about her; Eliza and Justin’s deadbeat dad (on the phone); Sasha and one of her clients, an alcoholic TV host (mainly via text message); Eliza at her AA meeting.

The panels are unusually large, crammed together with no gutter in between—usually six per page, but occasionally even fewer. The colors are bright and hand-painted, sometimes naturalistic but more often decidedly not. Eliza’s skin is generally an orangish red, Sasha’s a pale yellow, but the exact hue varies from page to page and panel to panel. In many places the art is deliberately raw, with the brushstrokes clearly visible and some areas left unfinished—the face mostly filled in but not the hair, say, or the clothes but not the skin. Textiles and backgrounds sometimes become almost abstract, an opportunity to play with pattern and shading rather than an attempt to depict the world.

This makes what might otherwise be simple scenes of two people talking curiously energetic and unstable. Even the quietest moments have a wildness lurking within them, a sense of things being on the verge of going to pieces or bursting into life. In the book’s most vivid sequence, Sasha and Eliza walk to the subway together after another of Eliza’s readings and have a long, raw conversation as they wait for the train. Sasha is enthusiastic, almost cloyingly solicitous; Eliza lashes out at her and then, for the first time in the book, opens up. “I don’t like myself very much these days,” she says. “I don’t know when I became this person—this person that’s so angry.”

As they talk, the panels expand and contract. Our viewpoint moves toward the characters, away from them, circling around, reframing the space. The red of the floor tiles, the yellow of the warning strip in front of the subway tracks, the green grid of Eliza’s hoodie seem to take on a life of their own. The atmosphere is restless, uncertain, a little unsettling, vibrant with possibility. At one point Eliza stands right on the edge of the platform, looking down at the tracks. She’s too close, and a train is coming—Sasha calls for her to step back but at first she doesn’t respond. The last panel before Eliza finally turns away is one of the roughest in the book: the brushwork is ragged, and a large section of the image is left uncolored, as if the book itself were on the verge of calling it quits.

Like Acting Class, Men I Trust ends with a form of betrayal. Sasha convinces Eliza—who has done some sex work in the past—to join her on a date with Andrew, her TV-host client. “It doesn’t have to be anything more than dinner,” she promises, but it quickly becomes clear that isn’t true. They go up to his hotel room, where he’s already half-naked, drinking heavily, erratic. Sasha has told him that she and Eliza are a couple. “I guess I figured it might get him to pay more,” she explains, unconvincingly. When Andrew goes down to the lobby for more drinks, Sasha invites Eliza onto the bed, then kisses her. She claims she’s setting up a performance for Andrew to walk in on but tells Eliza that “there is something between us. Something special.” After Andrew returns and immediately disrobes, Eliza leaves.

She and Sasha have one last argument outside—harsh, emotional, final. It’s not clear if this night was just Sasha’s attempt to draw Eliza further into her life and into a sexual relationship, or an attempt to sabotage their newfound intimacy or her own happiness or even Eliza’s sobriety, or some combination of it all. It’s not clear if either of them knows. “I really hope you work out how to be OK, Sasha,” Eliza tells her. “It just can’t have anything to do with me.” As usual, Parrish avoids tidy resolution. We see brief scenes of Eliza and Sasha, separately, meeting other people. The last few panels of the book are sketchy, and then simply blank. The words Eliza recited just before they met—the words from the poem that caused them to meet, that drew them together—seem to echo back: “Always falling into a hole. Then saying ‘ok this is not your grave, get out of this hole.’”

-

*

For more on Drnaso’s previous work, see my “Savage Torpor,” Harper’s, August 2018. ↩