W.E.B. Du Bois, the African American sociologist and historian and a cofounder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, was fond of the Latin phrase Semper novi quid ex Africa (out of Africa, always something new). Although of Greek origin, the phrase is most often associated with the Roman philosopher Pliny the Elder, who included it in his Natural History (77 CE). For Pliny, Africa was a place of strange and unusual creatures. For Du Bois, however, the continent was most remarkable for its contributions to human development. “It is probable that out of Africa came the first civilization of the world,” he insisted. From his publication of The Negro in 1915 until his death in 1963, in Ghana—where he was at work on an ambitious Encyclopedia Africana—he wrote against the conception of Africa as what Hegel called the place without history.

Du Bois’s project was twofold. He first sought to show that Africa did indeed have a history. From its “dark and more remote forest vastnesses came…the first welding of iron, and we know that agriculture and trade flourished there when Europe was a wilderness,” he wrote. Second, he aimed to explain how African achievements had been erased by the processes that produced European global dominance. The depiction of Africa as the place without history was the product rather than the cause of the enslavement and forced migration of over 12 million Africans, followed by the colonial conquest of the continent. In the course of this historical drama, he argued, “‘color’ became in the world’s thought synonymous with inferiority, ‘Negro’ lost its capitalization, and Africa was another name for bestiality and barbarism.”

This twofold pursuit was not unique to Du Bois. Beginning in the nineteenth century, African American intellectuals, understanding that their political fates were tied to depictions of Africa, had written counter-histories. They did so in fiction and poetry, from Pauline Hopkins’s Of One Blood (1902) to Countee Cullen’s Heritage (1925); by repurposing the colonial genre of the travel narrative, as in Martin Delany’s Official Report of the Niger Valley Exploring Party (1861) and Eslanda Robeson’s African Journey (1945); and by covering political developments on the continent in newspapers like The Chicago Defender and the Pittsburgh Courier. Scholarly publications like The Journal of Negro History, founded in 1916 by the pioneering African American historian Carter G. Woodson, and Black institutions like Howard University incubated the field of African studies. The first issue of the Journal carried an article entitled “The Mind of the African Negro as Reflected in His Proverbs,” which made the case that “a deeper and more extensive reading” of folk literatures “strengthens our belief in the ancient saying ‘Out of Africa there is always something new.’”

Howard French’s Born in Blackness: Africa, Africans, and the Making of the Modern World, 1471 to the Second World War continues this intellectual tradition. French, whose essays appear often in these pages, is the former New York Times bureau chief for West and Central Africa as well as the Caribbean and Central America. In Born in Blackness, he draws on his travels throughout the African continent and the wider Atlantic world and on extensive research in the primary sources and secondary literature to reconstruct Africa’s place in history.

Unlike Du Bois, who in The World and Africa (1947) argues that ancient Egypt is the African origin of human civilization, French starts in the fifteenth century, when new connections were formed among Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Americas. While Europeans are often the central actors in this story, Born in Blackness casts Africans on both sides of the Atlantic as the “prime movers.” Before the Atlantic slave trade, African societies shaped global commercial networks centered on gold and enjoyed political and economic parity with other states. In the age of the slave trade, African labor was of fundamental importance to the development of settler societies in the Americas and the broader global economy. Then, from the brutal conditions of chattel slavery, Africans universalized the idea of human emancipation, recast Blackness as a political identity, and laid the foundations for Pan-Africanism.

French writes not only to correct the historical record but to urge readers to understand how their world has been made by Africa’s contributions. Born in Blackness is therefore an entry into a larger debate about how to reckon with the past. In the United States, conflicts over the nation’s fractious history—including debates about Confederate statues, The New York Times’s 1619 Project, and school curriculums—have reached a frenzied pitch. French seeks to provoke a full-scale reconsideration of who we are as Americans. He writes in the book’s closing pages:

I believe that the sooner denial about the large and foundational role that slavery played in creating American power and prosperity is put to definitive rest, the better Americans as a people will come to understand both themselves and their country’s true place in world history.

Yet the history recounted in Born in Blackness contains lessons for Africa and Europe as well. French addresses Americans, but his book views the history of slavery and race here as one episode in a global drama. In this way, Born in Blackness counters the domestic perspective of the 1619 Project; what launches his story is not the settlement of the US and the arrival of Africans on these shores, but the fateful encounters between Portuguese traders and African empires. And rather than concentrating on the “peculiar institution” of American slavery, French tracks the development of plantation slavery from the island of São Tomé to the Caribbean and Brazil before he turns to the US.

Advertisement

A focus on our own national myths obscures slavery’s international scale. It offers too simple an answer to the question, What do we want history to do for us now? For Du Bois and his generation, historical narratives vindicating Black agency mobilized the past in service of revolution, drawing a direct line from what was before to an emancipation that will be. Our own history wars cannot offer such assurances. But by presenting Africa’s place in the world from the fifteenth century to the twentieth in unflinching, extraordinary detail, Born in Blackness offers a guide to how to answer this question.

The fifteenth century was the Age of Discovery. In our standard account of the period, Africa was first and foremost a roadblock to Europeans searching for easy access to the spices and silks of Asia—as in Christopher Columbus’s search for a westward path to the East or the circumnavigations of Bartolomeu Dias and Vasco da Gama. Only later, according to this line of thinking, did Africa become important, as the supplier of the enslaved women and men whose labor sustained the plantation economies of the New World.

Not so, says French. “The first impetus for the Age of Discovery was not Europe’s yearning for ties with Asia,” he writes, “as so many of us have been taught in grade school, but rather its centuries-old desire to forge trading ties with legendarily rich Black societies hidden away somewhere in the heart of ‘darkest’ West Africa.” The history of Iberian explorers begins on the west coast of Africa. European interest in the Americas and Asia was only a later development.

To understand why Portugal’s sights were set on West Africa, which was referred to as the “New World” before 1492, French again shakes up the conventional story. Rather than starting with the forces driving European exploration, he begins with the empires of Ghana, Mali, and Songhai. Ancient West African cities like Djenné (in present-day Mali) were part of far-reaching trade routes. (For instance, archaeological digs have uncovered glass beads from there as far away as Han China.)

The region’s prominence was based on gold. In the tenth century the Ghana Empire came to be known as the “country of gold” throughout the Mediterranean because it controlled the entrepôts where gold from the south was traded for salt and other essential goods from the north. Mali, which succeeded Ghana in the thirteenth century, controlled the nexus of three important river valleys—the Senegal, the Gambia, and the Niger—and had by the fourteenth century an estimated population of 50 million. Like its predecessor and its successor, the Songhai, the Mali Empire built its power on trade in gold and slaves, whom it used as laborers but also sold in North Africa.

In 1324 Mansā Mūsā, the ruler of Mali, arrived in Cairo with a spectacle of largesse, cementing Mali’s association with gold and slavery. Mūsā traveled with a delegation of 60,000 people, including 12,000 slaves, each of whom reputedly carried a fan made of four pounds of gold. (His camels and horses also carried hundreds of pounds of gold dust.) As impressive as the gold was, it was the number of slaves, French writes, that “may have reinforced sub-Saharan Africa’s reputation through the Near East as an inexhaustible source of Black bondsmen and women.”

Here French, like Du Bois before him, seeks to refute the idea that first Arabs and then Europeans, rather than Africans, brought the continent into global commercial networks. But even as he shares in this vindicating project, French has a different aim. He argues that if we recognize the complex state formations and global connections that characterized West Africa in the fifteenth century, we can better understand the encounter between Europe and Africa. The inequalities we are so familiar with today were not preordained, French insists; they were produced through exploitation and extraction as old as the modern world.

Advertisement

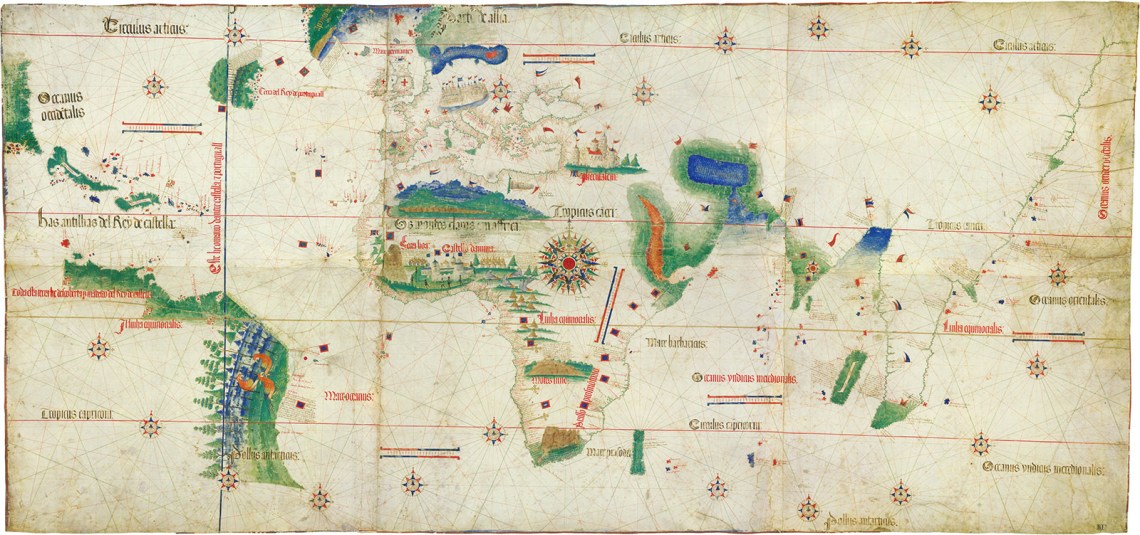

Mansā Mūsā’s arrival in Cairo generated feverish efforts to locate and better understand his mysterious kingdom and its wealth. One of the most important surviving maps from the European Middle Ages, the Catalan Atlas of 1375, identifies Mali and depicts its king, French writes, as “unambiguously Black.” He is described as “sovereign of the land of the negroes of Gineva [Ghana],” the “richest and noblest of all these lands due to the abundance of gold that is extracted from his lands.” His Blackness, though prominently represented, did not obviate his parity with European sovereigns.

In the early 1440s Portugal occasionally raided the African coast for slaves to offset the cost of its search for gold. By 1448 Prince Henry ended the practice in order to establish diplomatic relations with African rulers. “Although one rarely hears about it,” French writes, “mutual recognition of sovereignty and the full and complex range of statecraft…would dominate European relations with sub-Saharan Africa well into the seventeenth century.” These relations, he goes on, “involved the dispatching of ambassadors, the creation of alliances, formalized trade arrangements, and even treaties.” Gold from West Africa increased the availability of capital for new investments in the Iberian Peninsula and led to the creation of a new gold coin. These developments stimulated urbanization and social mobility across Europe.

Portugal’s monopoly on the gold trade in the Gold Coast propelled Spain westward from the Canary Islands in search of gold and silver. In 1494 the Treaty of Tordesillas divided the newly discovered lands of Africa and the Americas between Spain and Portugal; Spain was granted territories more than 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde Islands except for Portuguese Brazil, and Portugal everything east. Portugal thereby relinquished control of much of the New World. Many historians have seen this as being to Portugal’s disadvantage, but French writes that “this is clearly not how the Portuguese themselves experienced the breakthroughs of this period.” Having secured control of the Elmina trading post in what is now Ghana, João II of Portugal “began celebrating West Africa as the ‘Portuguese Main,’ and proudly appending Lord of Guiné to his other titles.”

The trade in gold launched an era of major economic expansion. But those shimmering riches did not compare to what lay ahead, when the prized commodity Africa offered was human beings. The transition to a period in which slave traffic dominated engagement between Europe and Africa was slow but consequential. It began when the Portuguese entered the inter-African trade in people, buying slaves from further down the coast in Benin to exchange with Akan communities for gold. Slavery had long supplied the Akans with laborers for agriculture, public works, and its military. They would typically be assimilated through manumission and marriage as a strategy of expanding the population. Before the introduction of Indian textiles into the African market, the goods the Portuguese offered were not coveted by the Akans; only slaves were.

Benin’s ruler soon ended the practice of selling war captives to Europeans, however, fearing that his power would be gradually eroded by the loss of people. This decision, and Portugal’s shift to the colonization of the island of São Tomé, contributed to the emergence of the full-scale transatlantic slave trade. French argues that if the Elmina trading post, “as a purchaser of slaves from elsewhere in Africa,” was “important as a catalyst for what became the Atlantic slave trade,” São Tomé “deserves an equal, if distinct renown—or infamy.”

At São Tomé, the modern sugar plantation was born. Large-scale sugar production had already been introduced in the Canaries and Madeira, but the São Tomé plantations were even bigger and more industrial in their highly specialized tasks for workers. Most significantly, they were the first to rely entirely on African slave labor. On São Tomé, the transformation of sugar into a mass commodity went hand in hand with the chattelization of African women and men. Here was the model for the New World.

The rise of the plantation economy predicated on African slavery, first in São Tomé and then in the Americas, illuminates the double valence of French’s title, Born in Blackness. First, the new Atlantic economy set in motion the “great divergence” between Europe and the rest of the world. Slave labor supplied the sugar, cotton, tobacco, coffee, and indigo that transformed European life. Sugar, which is high in calories, made it possible to feed more Europeans at lower cost. The wide availability of coffee facilitated the rise of the bourgeois public sphere, organized around the era’s new institution, the café. Slave-grown cotton fed the textile boom of the Industrial Revolution.

The Atlantic trade also reshaped the economies and politics of Europe. To purchase slaves, traders from imperial centers could not rely on the meager goods produced domestically and instead depended on suppliers across the European continent. As a result, French writes, trade with Africans stimulated “circuits of exchange within Europe” and “helped propel European integration.” And if, as the sociologist Charles Tilly argued, European state-making depended on war-making, the Atlantic world gave Europe a bigger stage and greater resources for building stronger, more organized states.

As Europe’s fortunes rose, Africa’s declined. Rather than creating strong states in West Africa, the slave trade “set into motion forces of heightened chaos and political destruction.” Selling rivals and captured enemies into the trade became a costly and brutal means of self-preservation. Amid new waves of international displacement, African states developed larger militaries and expanded the practice of slavery.

Political destabilization coincided with economic dependence. When Dutch traders flooded the Gold Coast with cheap, mass-produced foreign cloth, “local textiles were largely squeezed out of the market,” French writes, “leaving the Gold Coast more and more dependent on the export of raw natural resources.” What had begun as a relationship of approximate parity, with African states possibly having the upper hand, shifted toward a steep trade imbalance. It favored the Europeans.

Perhaps the most consequential effect of the slave trade in Africa was the “demographic and human catastrophe” it unleashed. Along with the 12.5 million Africans who survived the Middle Passage, another 6 million were trafficked to North Africa, to the Red Sea, and across the Indian Ocean. Historians estimate that about 12 million died en route to the Americas, either on the Atlantic or on the journey from the interior to the coast. Even before the onset of the transatlantic slave trade, Africa was comparatively underpopulated due to higher death rates from tropical disease. The unprecedented movement of people during the Atlantic slave trade, however, exacerbated this problem. As Britain and other parts of Europe experienced a population boom, which accelerated economic growth, Africa experienced a decline.

As for the second meaning of the title Born in Blackness: the categories of Africa, African, and Black as names for a political community did not precede the transatlantic slave trade but were invented during the experience of slavery. On the slave ships and plantations, enslaved Africans from diverse linguistic and ethnic communities forged solidarity and generated creole cultures. These connections spurred a tradition of Black resistance.

The birth of the modern plantation in São Tomé, French notes, also gave rise to the first large-scale slave revolt. In 1532, 190 slaves aboard the Misericordia rose up and murdered almost the entire crew. According to one story, following a 1554 shipwreck off the coast of São Tomé, enslaved men and women swam to shore and escaped into the thick forest. (Whether a revolt had taken place aboard is unclear.) The victors as well as those who escaped the plantations came to constitute a community of free Blacks, the Angolars, unknown to the Portuguese. In 1574 they launched a surprise attack and destroyed São Tomé city. Their early rebellion, French suggests, might be considered “one of the first acts in a long history not just of revolt, but in pursuit of a nascent if tentative Pan African ideal.”

French attributes this Pan-Africanism to the São Tomé revolt and its successors—from the 1760 Tacky’s War in Jamaica and Haitian independence in 1804 to the daring 1811 uprising led by Charles Deslondes on the German Coast of Louisiana. This is not how rebel slaves would have understood their actions; “Pan-Africanism” as an ideology and political project arrived later. But for French, these rebellions of enslaved African people point toward the ideal. They “drew people together around expanding ideas of shared Blackness.”

This early Pan-Africanism revolved around new political identities and remarkable information networks that radiated from large port cities like Kingston and Havana, crisscrossed oceans, and traversed plantations. Word of the Haitian Revolution, for instance, traveled on what the historian Julius Scott called the “common wind” of these Atlantic circuits, inspiring uprisings like the ones in Louisiana.* Future president John Adams marveled at the “wonderful art of communicating” that freed and enslaved Black people cultivated among themselves: “[News] will run several hundreds of miles in a week or fortnight.”

French wrote Born in Blackness to counteract the “symphony of erasure” that has obscured and denied Africans’ contributions. In this he echoes Du Bois’s aim in The World and Africa to overcome “the habit, long fostered, for forgetting and detracting from the thought and acts of the people of Africa.”

Published the year of India’s independence and a decade before Ghana’s, The World and Africa was a historical reconstruction that looked toward a future of decolonization. In the book’s last chapter, “Andromeda”—titled after the daughter of Cepheus and Cassiopeia, king and queen of ancient Ethiopia in Greek mythology—Du Bois concluded that

the fire and freedom of black Africa, with the uncurbed might of her consort Asia, are indispensable to the fertilizing of the universal soil of mankind, which Europe alone never would nor could give this aching earth.

He believed that, as Africans freed themselves from colonialism’s shackles, a truly universal humanism would be born.

Seven decades after Du Bois’s confident assurance, the prophecy of Andromeda can no longer be sustained. But in the absence of revolutionary possibility—or perhaps due to this absence—the writing of history has become the focus of intense political struggles. Many of these struggles have been less a search for usable pasts than an effort to expose the history of slavery and colonialism that has been hidden in plain sight. When Black Lives Matter protesters threw the statue of the slave trader Edward Colston into Bristol Harbor and defaced statues in Belgium of King Leopold, who once owned the Congo as his personal territory, they were asserting that colonialism and slavery were not merely part of the past. They insisted on seeing these cruel forces at play in the present.

Born in Blackness is also part of this contemporary conjuncture, and thus marks a new phase in the African American tradition of writing African history. It undoes the marginalization of Africa in our versions of the past and denaturalizes Africa’s contemporary inequalities. It asks what it would mean to memorialize the 1574 São Tomé revolt or the many forgotten instances of African agency and resistance. For French, transforming the way we perceive ourselves as citizens of the most powerful country in the world, and transforming how we understand the part Africans played in building it, are necessary steps toward justice and equality.

-

*

Julius S. Scott, The Common Wind: Afro-American Currents in the Age of the Haitian Revolution (Verso, 2018); reviewed in these pages by David A. Bell, December 19, 2019. ↩