The last time I was in Beirut was the fall of 2019, when Lebanon was in the throes of angry, hopeful protests. What started as street riots over a new tax had quickly ballooned into a national movement demanding an end to corruption and to the flagrant mismanagement of the country’s resources. It also called for sweeping away the entire Lebanese political elite, many of whom were the same warlords who had fought in the civil war of 1975–1990, had never been held accountable for it, and had gone on to entrench their power within the country’s deeply sectarian political system. The demonstrators, whose slogan was “All of Them Means All of Them” (i.e., get rid of all of them), rejected the mafia-like system in which the leaders of each religious community doled out favors, jobs, and public resources in exchange for loyalty while enriching themselves the most.

As it turned out, the protests were too little, too late. Lebanon was in the grip of an economic crisis that was about to get much worse. The exchange rate of the lira to the dollar was slipping on the black market; for years Lebanese banks had been offering unreasonably high interest rates to attract dollars in what many have described as a Ponzi scheme. By the end of 2019 the entire house of cards was collapsing. Banks set limits on how much money depositors could take out of their accounts, even as they allowed the country’s elite, who had hugely benefited from the shortsighted financial engineering, to move their fortunes abroad. The value of the lira plummeted, inflation soared, and the Lebanese thawra (revolution) stalled before it was halted by the advent of Covid.

By the following summer Beirut was exhausted. And then, on August 4, 2020, an enormous blast rocked the city. People’s first thoughts were of Israeli air strikes, of car bombs, of earthquakes. The truth turned out to be worse—an unimaginable, gratuitous, self-inflicted blow. Some portion of 2,750 tons of ammonium nitrate that had been stored at the port of Beirut for the previous six years—without proper precautions and unbeknownst to the public—had exploded, although the word “explosion” hardly describes what happened. In videos of the blast, one sees a plume of black then red smoke that suddenly turns into a white mushroom cloud expanding with incredible force. This is always the moment in which the camera or the person filming is knocked down and the video ends. The explosion was so intense that it was heard as far away as Cyprus; it gutted buildings, overturned cars, pulverized windows, knocked doors off their hinges, threw people across rooms. Hundreds were killed and thousands injured.

“Everyone within a two-kilometer radius of the port thought that the explosion was on their own street, in their own building,” writes Lamia Ziadé in her graphic novel My Port of Beirut. As that possessive pronoun makes clear, this is a partial, personal, impassioned account of a crime committed against the Lebanese people. As with other crimes—the civil war, the profiteering during postwar reconstruction, the political assassinations, the financial collapse—it has so far proved impossible to get a true explanation of it and to bring to justice those responsible.

Ziadé is an author and illustrator who grew up in Lebanon and now lives in Paris. Her previous books include the childhood and civil war memoir Bye Bye Babylon (2011) and Ô nuit, ô mes yeux (2015), a charming account of the lives of Arab divas. They alternate evocative, personal texts with illustrations whose bold, colorful style seems to hark back to hand-painted movie posters. The illustrations in My Port of Beirut are almost all reproductions of images that circulated following the blast and were shared and viewed compulsively by the Lebanese people as they collectively grappled with their shock, grief, and rage.

Ziadé’s grandmother, parents, brother, and sisters all lived near the port; their homes were destroyed, but they survived. Ziadé found herself, like so many in the Lebanese diaspora, agonizing over events from abroad. In Paris, she was distraught, horrified, sleepless, glued to her phone for updates. “I’m angry at myself for not returning to Beirut immediately after August 4,” she writes, “to support, shoulder, surround those who are there, bruised and traumatized.” And yet she was paralyzed, filled with dread at the thought of making the trip back to Beirut, a trip she had made many times before and that had become entwined with excitement and a dizzying fear. As a young woman, when she was a student in France, Ziadé returned to her family during every school break, even though the country was at war—a decision she finds insane now but that seemed natural back then. In one aside in the book, she tells of how in 1989 she flew from Paris to Cyprus, then took a ship that made its way under cover of night to the Lebanese port of Jounieh. As passengers were disembarking, the port was bombed by Syrian artillery. Two young girls, departing with their family in the opposite direction that night, drowned. Two days later the port authorities called to say that they had found Ziadé’s luggage, which had fallen into the sea.

Advertisement

For Ziadé, as for many other Lebanese, the port explosion capped a lifetime of trauma:

My whole life, and that of those more or less close to me, has been steeped in violence. Always. I am alarmed by the amplitude and extent of this violence, which has become so familiar that it seems natural to me.

Her book is an attempt to come to terms, almost in real time, with the unfolding of yet another national catastrophe and with the questions, memories, and emotions it provokes.

On August 4 the first indication that something was wrong was the huge plume of smoke. At 5:54 PM, the phone rang in the Karantina fire station. A brigade of nine firefighters and one paramedic headed to the port. Among them was Sahar Fares, a twenty-seven-year-old firefighter whose smiling face, as she leaned out the window of a fire truck, became a national symbol. She and all her colleagues, who headed to the port with no idea of what was stored there, died within minutes of arriving. Her body was identified by her engagement ring.

Much of the book comprises portraits of the blast’s victims and its survivors—stories of heroism, blind luck, and tragic happenstance. People died because they had gone up to a roof to film the fire; others lived because they had opened a window, allowing the shock wave to pass through. A baby was taken out of its cot at just the right moment; a father who had traveled to Beirut to visit his sick daughter died in front of her, sitting on her hospital bed. People just missed each other, just found each other; strangers saved each other’s lives.

Pamela Zeinoun was a nurse at the Orthodox Hospital. Ziadé reproduces a press photo of her taken just after the blast. Zeinoun has extracted herself from the debris and taken three premature babies from their broken incubators. She is on the phone with her mother, telling her she is alive. She is about to head out of the hospital, carrying the three infants, and make her way through the devastated city to other nearby hospitals that have also been destroyed, and then onto the highway, where a car will stop for her and take her to a working maternity ward. The babies survived.

Ziadé’s portraits of her fellow citizens are a rebuke to the country’s leaders. Michel Aoun, the president at the time, is “so hated,” she writes,

that he didn’t dare go down to the port or to the most affected neighborhoods. He did not express regrets, apologies, condolences—nothing. Neither him nor any of the other politicians. No regrets and certainly no resignations.

In a TV interview, Aoun is asked a softball question:

“Mr. President, you have surely followed the events on television, the images broadcast on the news…is there a particular face that has stuck out to you among the victims? Are there certain names that have stayed with you?” The response comes immediately, the president frankly says no, he doesn’t really know the names of the victims.

To the callousness and cowardice of these leaders, Ziadé contrasts the ways that people went to one another’s aid with generosity and courage in the immediate aftermath of the blast, ferrying the wounded to hospitals on the back of motorcycles, in taxis, and in overcrowded ambulances: “The mutual aid in Beirut during the weeks after the explosion is as spectacular as the blast itself.” On August 5 people were out in the streets cleaning up the mess. They were also telling the international community not to send any aid through the government, which they didn’t trust to administer it. In the years since, it is local and international NGOs that have helped people repair their homes, replace doors and windows, and rebuild their neighborhoods.

But the damage of the explosion was immense. It destroyed buildings that had resisted “the two plagues that have blighted the city over the course of past decades: the war, and real estate development.” Three hundred thousand people were left homeless. The property damage to the neighborhoods near the port has been estimated at $15 billion. Months after the blast, survivors were still picking shards of glass out of their bodies; Ziadé’s sister tells her that her carpets shine with glass dust, impossible to remove.

Advertisement

There has been a port in Beirut since ancient Phoenician times. In the nineteenth century, when the city was part of the Ottoman Empire, its rulers hired a former French naval officer, Comte Edmond de Perthuis, to build a new port west of the ancient one. This port was expanded in the 1930s under the French protectorate, and again in the mid-1960s under President Fouad Chehab. Chehab, who had headed Lebanon’s armed forces, was a modernizing if autocratic leader. In 1970 he was expected to run for reelection, but in a famous speech he declared he would not, saying that the country remained under the sway of venal, feudal political leaders. Suleiman Frangieh, one such leader, was elected president by a single vote in a controversial parliamentary session. Ziadé sees this as a turning point in the country’s modern history:

A hazy and insidious process was begun in 1970, by a handful of men with no vision and no scruples, determined to preserve their privilege, power, and money, by placing at the head of government a mobster, the embodiment of feudalism and corruption, who, day after day, after day, after day, led Lebanon to the gates of hell. Several times to the gates of hell, and after fifteen years of war this mechanism that consists of removing, at every echelon, the most competent and upstanding men, the nuisances, for the profit of incapable corrupt men, is still the same today.

One of the competent and upstanding men in Ziadé’s story is her great-uncle Henry Naccache; he is also a link to the port itself. As a leading member of the Executive Council for Major Projects, he oversaw the port’s expansion and many other public works in the 1960s under Chehab. After Chehab left power, Naccache and others were accused of corruption and politically sidelined. He was working as a volunteer high school teacher when he was assassinated at a checkpoint in 1976.

Meanwhile, the port was being managed by a private concession granted to the Lebanese businessman Henri Pharaon. During the civil war, parts of it were destroyed and seized by the Lebanese Forces, a Christian militia. As the war came to an end, the Lebanese government formally took control of the port. The country’s different factions all wanted a piece of the lucrative site. They included the political parties that represented Lebanon’s many religious communities, including Christians, Druze, Sunnis, and Shias, who have found their champion in Hezbollah, the powerful Iranian-backed militia that has fought Israel in the south of the country. Despite being enemies in the civil war, these groups found accommodations with one another afterward.

In the early 1990s a “temporary committee”—on which all factions had a seat—was appointed to run the port. But the committee’s responsibilities and the ownership of the port remained undefined, its activities unregulated, its books unaudited. In 2019 the port handled 78 percent of Lebanon’s imports and 48 percent of its exports, totaling some $20 billion in goods. An estimated $1.5 billion in customs went uncollected. As the local news site The Public Source noted in 2020, “For years, it has been an open secret that the Port of Beirut is characterized by institutional corruption and smuggling.”

Ziadé mentions the investigative journalist Riad Kobaissi, who has been exposing corruption at the port for years. In an interview last year, Kobaissi explained that the customs authority there is “the microcosm of Lebanon.” The country’s political parties “accuse each other of being thieves and then again, they form the government together.” In the same way, at the port each political party has its men and gets its share of the many illicit activities going on. No one wants to be held accountable for the explosion or to face public scrutiny. But the truth, says Kobaissi, is that

someone put a gigantic bomb in the middle of Beirut. They did it out of stupidity or meanness, on purpose or because they had other things on their mind or because they were only thinking about money. All reasons are the same. This is our Chernobyl.

The ammonium nitrate (a chemical that is used to make fertilizer and explosives) arrived in the port in 2013 aboard a Russian-owned vessel flying a Moldovan flag and headed from Georgia to Mozambique. It made an unscheduled stop in Beirut, reportedly hoping to pick up extra cargo; port officials deemed it unseaworthy and impounded it for not paying port fees. A judge ordered the cargo brought ashore in 2014, and in 2018 the ship sank in the port. The cargo sat in Hangar 12 for six years, improperly stored next to flammable materials: twenty-three tons of fireworks and a thousand car tires.

The director-general of Lebanese Customs, Badri Daher, was detained following the explosion, as were a number of lower-level port and customs officials. But investigations have now revealed that many high-ranking government figures—including then prime minister Hassan Diab and President Aoun—as well as civil servants and military and security officials were aware of the presence of the chemicals. Customs officials at the port sent at least six letters from 2014 to 2017 alerting authorities to the danger and asking for instructions. A Lebanese State Security report revealed that one letter sent in July 2020 recommended securing the chemicals in the hangar immediately.

The official explanation has been, almost from the start, that a team of Syrian welders, who were sent on August 4 to work on several doors at the hangar, accidentally started a fire that ignited the ammonium nitrate. They left before the explosion took place. But an investigation by Forensic Architecture and the Egyptian news site Mada Masr—based on photographs of the conflagration and the condition of the hangar’s skylights—produced a “unique heat map of the interior of the warehouse” that suggests that it is unlikely that the fire originated near the doors on which the welders were working.

It has been equally difficult to ascertain who, behind layers of shell companies, owned the ship and its contents. According to an Al Jazeera report, the shell company that owned the ammonium nitrate is linked to three Syrian businessmen who are under US sanctions for links to the Bashar al-Assad regime; they are also connected to a bank in Cyprus that was shuttered as a result of US sanctions. It was accused of money laundering, being used by Hezbollah, and facilitating the acquisition of chemical weapons for the Syrian government.

While survivors and relatives of the dead have continued to protest and call for an independent, international investigation, the leaders of Lebanon’s sectarian system have closed ranks. Having at first promised that those responsible for the blast would be brought swiftly to justice (in “five days,” a special committee formed by the government said), they have obstructed and obfuscated at every turn, making it abundantly clear that the last thing they want is an impartial, in-depth investigation. They have refused to be questioned or to lift the legal immunity their political positions give them. They have removed one judge from the investigation and hamstrung the current judge, Tarek Bitar, by initiating endless lawsuits against him.

The men whom Bitar has sought unsuccessfully to call in for questioning and charge with criminal negligence span the political spectrum. They include the security officials Tony Saliba and Abbas Ibrahim and the former ministers Ali Hassan Khalil, Ghazi Zeaitar, Youssef Fenianos, and Nohad Machnouk. Earlier this year, after a long pause in the investigation caused by legal complaints, Bitar announced that he would resume his work and issued new warrants. The country’s public prosecutor, Ghassan Oweidat—who has himself been charged in the case—challenged Bitar’s jurisdiction, and the investigation once again ground to a halt. Lebanese politicians have accused Bitar of being politically motivated, vengeful, crazy, and following orders from the US. Hezbollah has called for his dismissal.

In the midst of all the stonewalling and conspiracy-mongering, questions have proliferated: Why were the chemicals stored in the hangar? Had some of them already gone missing before the explosion? (An assessment by the FBI reportedly concluded that just 550 tons of ammonium nitrate had exploded.) Was the ammonium nitrate destined for Hezbollah or perhaps the Assad regime? How did it ignite in the first place? Was it an accident or an act of sabotage?

“Many questions and few definitive answers, but one thing is sure: Hezbollah and the politicians in power are undeniably responsible,” Ziadé writes. “The rage, the hatred, the anger of the Lebanese people assumed a single target from that point on—the mafioso regime that led us here, that knew.”

And yet all this righteous fury has not been enough to dislodge the country’s leaders, to whom many Lebanese are still loyal, or at least to whom they can see no viable alternatives. Ziadé wrote her book in the four months after the blast, “in the heat of the moment, with urgency, rage, and despair.” Toward the end of this period, she sums up the situation: the same leaders are still in place,

the thawra is savagely repressed, the economic situation is catastrophic, several assassinations have taken place, visibly linked to the port explosion, whose investigation is a great farce. The Lebanese people are distraught, hopeless.

Her conclusion is that “the system is stronger than a quasi-nuclear explosion.”

This remains true today. The country’s political parties and strongmen remain in power, clinging like barnacles to the sinking ship of state. A caretaker government is in place while they argue about who the next president should be. Negotiations on an IMF bailout have stalled over the authorities’ unwillingness to carry out economic reforms. The head of Lebanon’s central bank, Riad Salameh, is the target of a French investigation that has led to an international warrant for his arrest on charges of embezzlement. The Lebanese lira has plunged from 1,507 to the dollar to nearly 100,000, three quarters of the population are unable to meet their basic needs, and public electricity production has shut down, forcing people to rely on private generators.

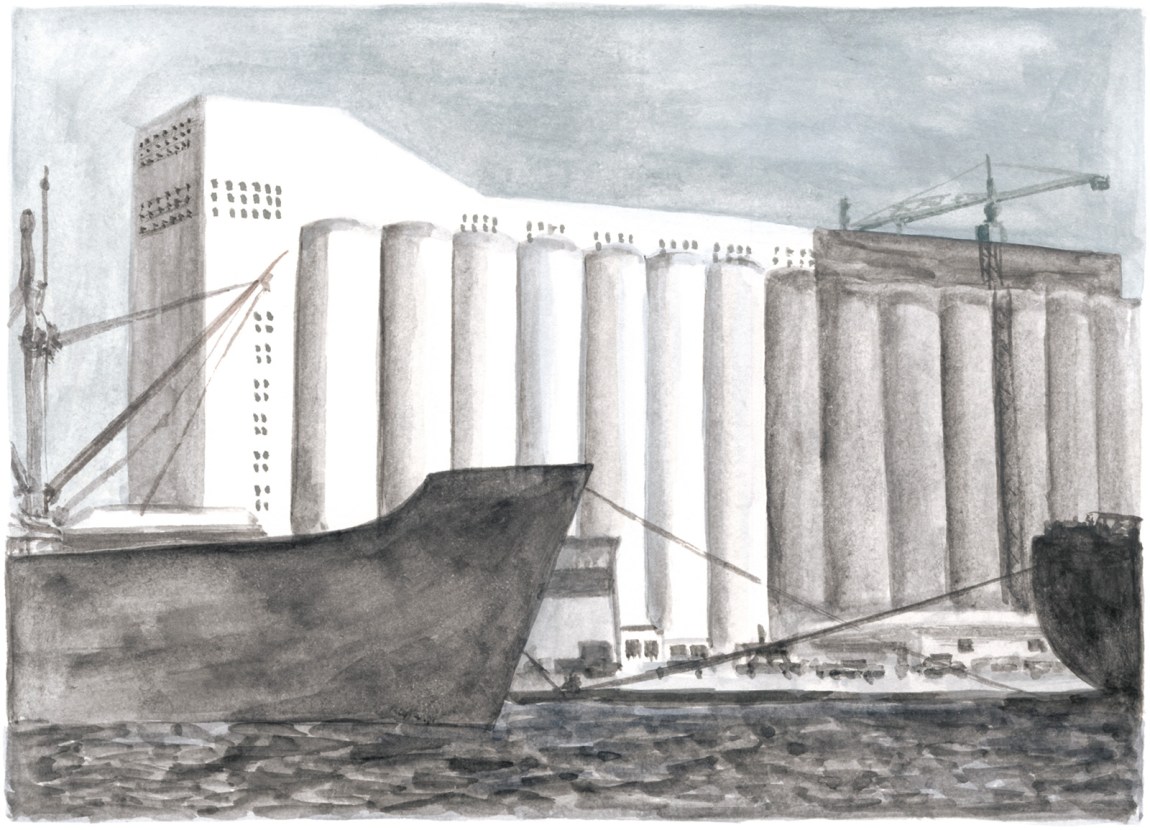

Ziadé was born in 1968, seven years before the beginning of the civil war, and the same year the port’s enormous grain silos, which store the wheat the country needs to import, were built. The silos, she writes, have always struck her as

the most unshakable symbol of Beirut, barely scratched during the fifteen years of war, standing so tall, so white, in the prodigious light of the port, as majestic as snowy Mount Sannine towering over them in the distance.

They absorbed the force of the explosion, protecting the buildings beyond them and sparing many lives. At the end of My Port of Beirut, Ziadé returns to the silos, which are devastated but still standing:

Since August 4, the silos have been photographed from a single angle, the side of the explosion. They are a gaunt, disfigured, mutilated, monstrous carcass. Seen from the other side, the west side, they are still very white and very straight, mostly intact. I see it as another symbol, that all is not lost. All the more so because the west side is the side that catches the light. The light that comes from the sea. The light of the setting sun.

Since Ziadé finished her book, more of the silos have collapsed. The government plans to tear down what remains of them as part of the port’s reconstruction. But others argue that they should be preserved as a memorial to the blast’s victims, a reminder of this outrageous calamity, and a promise to end the impunity that has sunk the country so low. As the urbanists Mona Fawaz and Soha Mneimneh have written, Lebanon’s political class shouldn’t be allowed “to erase yet another one of its crime scenes.”