This essay was delivered, in slightly different form, as a lecture at the Sixth Annual Stuart Hall Public Conversation in London on February 11, 2023.

In Familiar Stranger, Stuart Hall’s memoir (written in conversation with Bill Schwarz), which was published in 2017, three years after he died, Hall recalls a crucial sight on a London street in 1951, shortly after he had left Jamaica for Britain to take his place as a Rhodes scholar at Oxford. As he passes Paddington Station he sees “a stream of black people spilling out into the London afternoon…too poorly dressed to be tourists.” “Who were they,” he asks, “and what were they doing here?” It turns out they were the “advance guard” of the “black Caribbean, post-war, post-Windrush migration” that would transform the face of Britain. But the young black student feels no affiliation with these migrants who have arrived in the UK from a part of the world that he thought he had left behind, that he both sees and can no longer see—in fact has never truly seen—as his home.

Over the past few years the story of the Windrush—one of the first ships of Caribbean migrants to arrive in the UK, in 1948—has garnered attention as just one, albeit extreme, example of the racist cruelty of the British state toward migrants, welcome to its shores for only as long as their labor is required. More than fifty years later, many became targets of enforced deportation, regardless of whether they were born in the UK or arrived here as young children. This story is not over. In early January it was reported that Home Secretary Suella Braverman is set to abandon twenty-eight of the thirty recommendations made by the government’s formal Windrush inquiry, launched after the deportation scandal broke—for example, recommendations to increase the powers of the independent chief inspector of borders and immigration and to create the post of a special commissioner who would speak up for migrants. Independent scrutiny of the government’s dehumanizing migration policy and laws, insofar as it ever existed, will effectively be shut down. Migrants will have no voice, without which their ongoing claims for historical remembrance, for redress and compensation, are bound once more to fail.

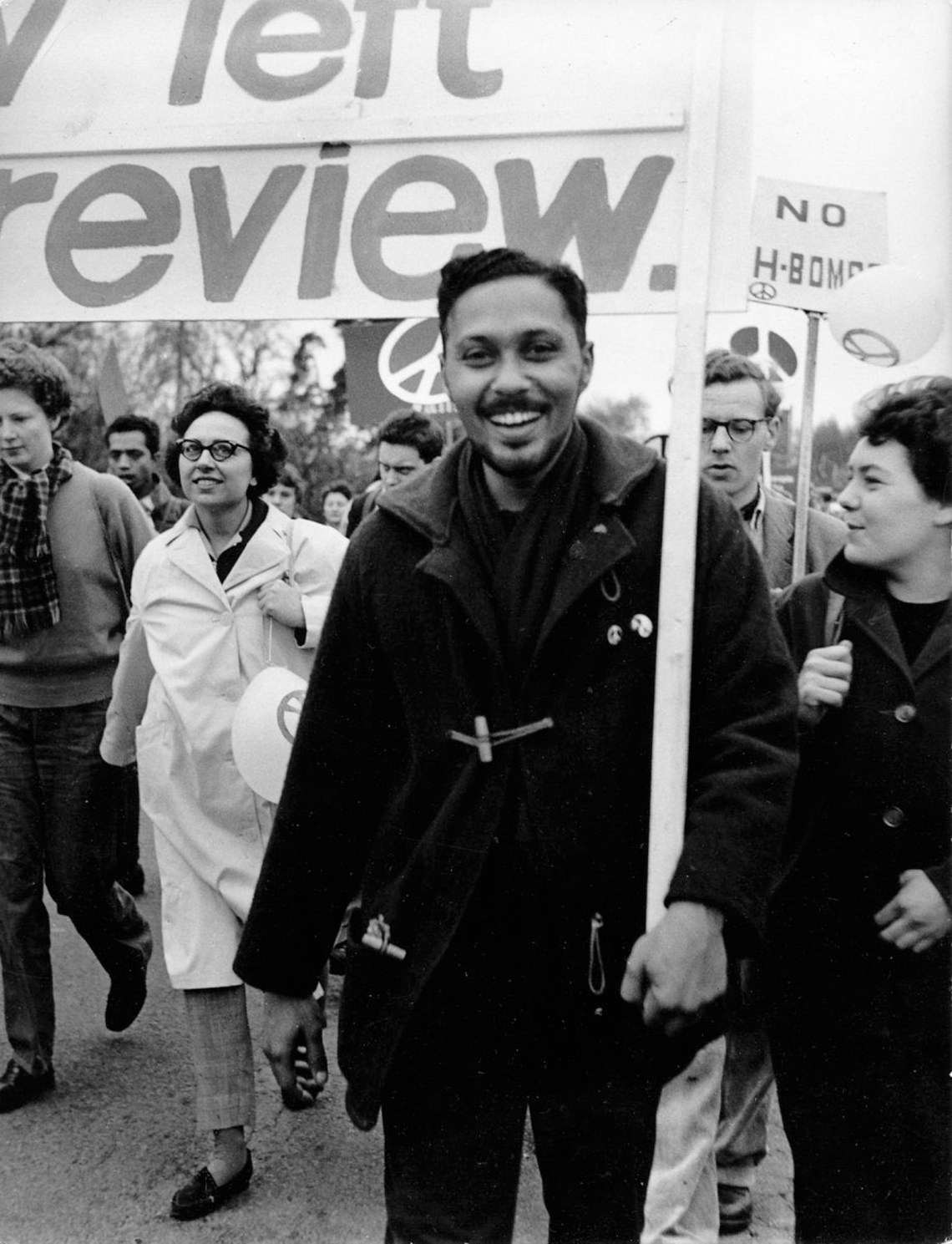

In many ways that kernel of experience on the London streets became Hall’s guide. (In Familiar Stranger he returns to it three times.) Hall is famous as one of the founding figures of cultural studies in the UK, relentless in his critique of capitalism while insistent on the political importance of popular cultural expression, from black music and film to street life and protest, giving each form its due status as a place where the worst of a historical moment is both registered and fought against. He was also one of the first such critics to recognize that no social analysis can afford to ignore the death-dealing and enduring effects of colonization and race. Hall was above all an essayist, preferring the form of writing that allowed immediate intervention into public intellectual life, and his prodigious output included the coedited collection Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State and Law and Order (1978), “The Great Moving Right Show” (1979), and The Hard Road to Renewal: Thatcherism and the Crisis of the Left (1988), to select a few of the most influential early works.

Since his death, the race to publish his writings has not ceased: Selected Political Writings (2017), Essential Essays (two volumes, 2019), the essay selection Race and Difference (2021), with more in the pipeline. Among other things, that early moment in his life allows us to take the measure of an often overlooked component of his work: his passionate commitment to understanding how social formations affect the deepest registers of the human mind. Hall experienced that 1951 encounter as revelatory: “For them and for me…a fateful moment of transition, frozen in time.” “What I thought I had left behind as an unresolved dilemma…had turned up to meet me on the other side of the Atlantic.” He had anticipated “all sorts of new beginnings” but had “never imagined London would secrete this explosive little time bomb from the past.” His world turned “inside out…as if the ‘real’ Caribbean which at home had remained beyond my reach had come to meet me in, of all places, England.”

This young man is haunted. It is the racial history of the Caribbean, its ongoing legacy of inequality and despair, that sent these migrants on their journey and that suddenly confronted him on the London streets. The Hungarian psychoanalysts Nicolas Abraham and Mária Török, émigrés to Paris in flight from persecution—Abraham on the eve, Török in the aftermath of World War II—created the term “transgenerational haunting” to describe how unspoken histories embed themselves in the most hidden recesses of the unconscious mind, first as an individual matter, when the next generation shows all the signs of having registered the psychic anguish of a previous generation, its secrets and lies, and then as no less part of collective life, when silenced or forgotten historical traumas slowly insist on being heard: the genocide of the Jews, which kept recurring in the stories of the children of Holocaust survivors, the patients whom Abraham and Török treated in Paris after the war; South Africa, in its failed struggle to lay the ghosts of apartheid to rest; and—we might add—Jamaica, whose denial of its slave-dependent history (the family of Hall’s mother owned slaves), its colonization by Britain, and its continuing investment in the forms of racial inequality and oppression endemic to both slowly enter the psychic consciousness of the young Stuart Hall.

Advertisement

“I wonder,” he writes, “if inside my family life this displaced larger history was in some way being restaged, in its own theatre, with its own disturbing psychic properties.” “Though buried and repressed,” he elaborates in his 1982 essay “The Empire Strikes Back,” the traces of such a history “infect and stain many strands of thinking and action, often from well below the threshold of conscious awareness.” We have moved into the realm of the unconscious, where what cannot be spoken leaks into the internal world and spreads like an infection or a stain. Without necessarily realizing what was happening, Hall had set himself a lifelong task:

These childhood experiences represented for me a slow disentangling of threads, a process of disenchantment and disaffiliation, pointing towards a radically different path ahead: an unpleasant experience, replete with gaps, contradictions, evasive silences, guilt and rage.

He is describing a threefold trauma: the founding violence of slavery and colonialism; the subsequent denial; and the enraged, guilty, anguished process of memory itself. “Post-mortem terror,” an expression Hall takes from Richard Wright writing in the aftermath of Ghanaian independence, can cover all three.

The familial silence on Jamaican history, above all his mother’s accommodation with the drastic racial inequalities that are its legacy, plays a crucial part in his decision to leave. The stakes could not have been more serious. If he stays, he does not think he will survive. At one point, when he is packing his bags for the journey on which his mother will accompany him before returning home, she condones a British newspaper article arguing that blacks should be expelled from the UK. We are not told how she reacts when he points out that by moving to England, which for her represents a major social and racial ascent for her son, he is about to become such an unwelcome black himself. (Although he himself is not strictly a migrant, “every Jamaican,” he writes, “is the product of a migration, forced or free.”) It is then hardly surprising that the outpouring of impoverished migrants from Paddington Station onto the Bayswater streets should strike him with all the force of the return of the repressed: “this explosive little time bomb from the past.”

As I started to read and reread Hall’s writing I realized I had been utterly unprepared for how quickly and fully the vocabulary of psychoanalysis—amnesia, disavowal, misrecognition, fantasy—saturates the scene of politics. Before we have time to orient ourselves in his writing—certainly before he knows where or who he is—the building blocks of a psychoanalytic project are in place. We are talking about a radical disorientation of the subject, whose unraveling—not resolution—will become the core of his intellectual, political, and inner life’s work. These lines read to me very like a psychoanalytic manifesto:

My argument turns on what can, and cannot, be imagined. And on where the past enters consciousness such that it can, further, inform the historical present, and become worldly. In other words, it’s to create a collective mentality which, far from being paralysed by the disavowals of the past, would allow new generations to engage strategically with the past, to become a properly historical force and to reach out to the world.

It is hard not to read in these remarks an emerging commitment to psychoanalysis, or the version of it expressed in Freud’s famous dictum “Wo Es war, soll Ich werden,” which can be read either as a call to strengthen the ego’s control over the unconscious or as a move in the opposite direction (the patient must allow breathing space to the more troubled and unmasterable domain of unconscious drives). Crucially, for Hall, the aim is to create a “worldly” subject, attuned to past injustices, which would mean breaking the silence on race and colonialism that, until very recently, has for the most part prevailed in the analytic consulting room.

For Hall, this is a political task that involves immersing himself in the darkest core of the human mind. “I have never believed in snatching some simple good alternative out of the mess. I think we are always, always working on the mess,” he writes in his Pavis lecture on multiculturalism in 2000. Only if you confront the “mess” of things, delve beneath the surface, and let in the silenced voices of history clamoring at the gate is there the slightest prospect of understanding, let alone transforming, the nightmares of our contemporary world.

Advertisement

Hall is not idealizing the unconscious—he ends his 1987 essay “Psychoanalysis and Cultural Studies” with reference to the violence and aggression that psychoanalysis recognizes in us all. One thing is clear: negotiating this inner space is interminable. Hall offers no prospect of an identity at peace with itself. “I cannot become identical with myself,” he wrote in his 2007 essay “Through the Prism of an Intellectual Life,” words that Schwarz chose as one of the epigraphs for Familiar Stranger and that convey the fragile nature of the self-knowledge on which we think we can rely in order to orient ourselves. The other was Madame Merle’s question in Henry James’s The Portrait of a Lady: “What do you call one’s self? Where does it begin? Where does it end?” (James was one of the writers who had the greatest impact on Hall.) Identities that flounder, moments when we lose our way, contain psychic truth. They bear witness to both the infinite complexity of unconscious life and our deep implication in the ills of the world, through which we must continue to struggle.

I think it is this founding history and its afterlife that make it possible for Hall to be so alert to aspects of British politics that fall outside the remit of the traditional left. He himself traces his political awareness to the Suez Crisis and to the Soviet occupation of Hungary, both in 1956, which laid bare the ills of empire on its two antagonistic, militarily invasive flanks. A year later, in one of his first essays, Hall described how “the disorderly thrust of political events disturbs the symmetry of political analysis.” Something escapes our understanding. He was already attuned to the ungraspable dimension of politics, which led to his startling and widely influential analysis of Thatcherism as a form of collective insanity, or a world in thrall to the logic of the dream. For Hall, Thatcherism—a term he helped popularize—would fully submit only to an analysis willing to broach the innermost psychic components of political identity. How did such a damaging ideology and program manage to exploit so deftly the “diffuse and often unorganised social fears and anxieties” of the British people? How could Thatcherism lead vast swaths of the public, including the working class, to vote for policies so manifestly against their social and economic self-interest? In 1983 the Conservatives gained 43.9 percent of the popular vote, a percentage never seen before and that, despite the past ten years of dismaying electoral victories, has not been matched since.

Though Hall does not go so far as to deploy Freud’s concept of the death drive, he was offering an analysis of political self-destruction in no uncertain terms. Many on the left would never forgive him for dispensing—once and for all, one might argue—with the form of Marxism that pinned its hope on the revolutionary consciousness of the working class, and with the concept of economic or class determination that upheld it. His suggestion that class could no longer be relied on to secure political party affiliation was met with outrage. In a 1959 piece entitled “The Big Swipe,” which he wrote as an Oxford scholar for Universities and Left Review (the precursor of New Left Review, of which he was the first editor), he politely, or impolitely, suggested that if his most vocal critic, the Marxist historian E.P. Thompson, “got out on the knocker instead of on to the shop-floor”—meaning went out in the streets and knocked on people’s doors—“and said to the first head that came round the corner, ‘Vote Labour,’ he would see what I mean.” “Because ideas do not spring out of thin air,” Hall commented, “the left tends to believe they do not matter.” Giving them their due means recognizing, way beyond the concept of relative autonomy, the subjective factors of any political moment and their internal dynamics. (The mind is its own place, the mind has a mind of its own.) This is a domain that, without ever having to name it, the right has always best known how to manipulate.

If Thatcher tilled this terrain to perfection, the ground had been well prepared throughout the 1970s by a creeping Conservative authoritarianism wedded to the state apparatus of constraint, which Hall described as the steady move toward “a kind of closure in the apparatuses of state control and repression.” This is something that today’s proposed legal clampdown on protests and on strike action in the UK is repeating, indeed exceeding: protests will be banned before they even happen, strikers who refuse to supply a government-imposed minimal service in areas of the economy deemed essential will face the sack. Under Thatcher, the social market values of competition became untouchable, alongside the enemies of competition: overtaxing, welfare coddling, handouts by the state—each one accused of undermining the idea of an autonomous, self-centered political subject who proudly takes care of themselves at the cost of pretty much everyone else. It was a heady mix of authoritarian populism—a term used by Hall to indicate a process irreducible to state power—combined with an idealized capitalism, sabotaging the postwar social democratic consensus.

As the project struggles on long after Thatcher’s demise, Hall marvels at its enduring ability to couple virulent free marketism with a “massive dose of social revanchism masquerading under the umbrella” of Little Englandism and the family. Since the 1950s “a profound historical forgetfulness” had overtaken the British people. Only a militant nationalism that projects its own past violence onto hatred for the indigenous and migrant nonwhite population could entrench itself with such unremitting force.

Imperial decline coupled with recession gave racism its cue. People had been “scared” over to Conservatism, he argued in “The Great Moving Right Show”: “The great syntax of ‘good’ versus ‘evil,’ of ‘civilised’ and ‘uncivilised’ standards, of the choice between ‘anarchy’ and ‘order,’ constantly divides up the world…into its ‘appointed stations.’” Hall is pinpointing the unconscious grammar of state-sanctioned violence against the excluded other, justified by an ideology that places whites at the forefront of a “particular, unique and uninterrupted progressive history,” “an ‘advanced’ civilisation crowned by a worldwide imperium.” It is surely no coincidence that these thoughts about imperial greatness, whose fantasy lingers long after the reality has died, arise when he returns once more in Familiar Stranger to reflect on that founding Bayswater scene. Those Caribbean migrants had no idea what they were in for.

To say Hall’s interpretation was unorthodox on the left is, therefore, an understatement. What drives nations “crazy” (his word) is the dissolution of past glories. Chauvinism in its Little England form is “deeply irrational, largely unconscious, defensive and abreactive.”* At the time he was writing, Brexit was still a pipe dream of the far right. But this did not stop Europe from becoming “the fetish, the displaced signifier, the repository into which all those dark and unrequited elements of the British psyche have been decanted: the hatred of all foreigners, not just black or brown ones.” For Hall, only the Conservative Party knows how to exploit “this heady ensemble,” this ugly mix, the one “popular current of feeling in the country into which a disaggregated party of the right can tap.”

Today, of course, the far right is more vocal than ever. It has also chalked up a chilling set of electoral victories across the globe, from Hungary to Turkey to India, from Italy to Sweden. Hall could have been talking about the world of Jair Bolsonaro and Donald Trump, whose removal from office in no way signals the collapse of the political realities they crafted out of hatred, nor of their political ambitions.

Thatcher’s genius was to personify and secure the “linkage” between an “inchoate surge of feeling in the country and the main thrust of policy in government and the state.” It was a vast and obscene co-opting of unconscious forces in the name of state power, what Noam Chomsky famously described as “manufacturing consent.” “Obscene” is again Hall’s word, this time for what the Tories did to the National Health Service. (One can only wonder what word he would have come up with to describe what is happening to the NHS today.) For many, among whom I include myself, the radical potential of psychoanalysis is its critique and disruption of what passes for the norm. Under Thatcherism—indeed, this is the very heart of Hall’s analysis—the forces tapped by psychoanalysis are instead conscripted into service of the norm.

It was one of Hall’s unique gifts to offer analysis of the moment as it unfolded before our eyes. I am sure I am not alone in having found his talks exhilarating in ways I could never quite understand, given that the news he relayed with such energy was almost unremittingly dire. Hall offered his readings as interpretation and self-commentary, tracing his own intellectual path. It is the task of theory to keep track of both political life and itself. Psychoanalysis was, as he saw it, an “interruption” in the study of popular cultural expression and activity, insofar as psychoanalysis foregrounds the question of the unconscious, something about which, in its first stages, cultural studies had had absolutely nothing to say—no more than it did on the issues of sexuality and gender at the heart of feminism. Indeed, as Hall writes in “Psychoanalysis and Cultural Studies,” “it walked and talked and looked at and attempted to analyse a culture, a human society as if it had no sexuality in it, as if the subjects of culture were unsexed.” (Since he is one of the founders of cultural studies, I think it is fair to say that the person he is criticizing here must also be himself.)

On the other hand, purely sociological accounts of human motivation and behavior, which focus on the social determinants of our actions, leave no room for complex psychic processes through which we try to secure the contours of the mind, such as when we project onto others the most hated parts of ourselves, others whom we then feel licensed to destroy. For Hall, the question of subjective identity is foundational to understanding agency and politics. But without the idea of a disruptive unconscious, we have no explanation for the fact that identities, often fraught and at odds with themselves, are not so easy to fix in place. “Identities are sliding,” he writes in “Fantasy, Identity, Politics” (1989). “You have to come to a full stop, not because you have uttered your last word, but because you need to start a new sentence which may take back everything you have just said.”

Hall is trying to let as much air and movement into our political and psychic lives as is humanly possible, which might also do as his definition of culture. It then falls with renewed urgency to culture itself to make that more open and flexible reality the impetus of change and a cause for celebration. Rivington Place, the first art gallery in the UK dedicated to diverse art, opened officially in 2007. It was his brainchild, for which he secured the funding and which he championed from the outset, and it became a brilliant and unique showcase for black visual artists.

Hall’s critique of the left in the name of more mobile forms of identification was therefore his bid for freedom. If every component of our social and political being hung unfailingly together, there would be no room to maneuver, no point. His commitment to cultural activity was at the very core of his politics. For Hall, psychoanalysis offers a vision of the human psyche as entrapped by its own histories, and also as the site of creativity that challenges the mind’s worst intentions for itself.

His critique of reactionary discourse on the family and sexual normativity surely follows. “The idea that, at the end of the twentieth century, after the revolution in the position of women and in sexual attitudes we have passed through,” Hall wrote in “Parties on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown,”

it would be possible to advance the “modernisation” of British society by an ideological commitment to the monogamous nuclear family as the only credible and stable family form, gives “modernity” such a deeply conservative inflection that it hardly deserves the name.

He was critiquing the legacy of Conservative government but also Tony Blair, on the path to his first election victory in 1997, whose positions on family values, one-parent families, and sexuality hardly conformed to the progressive image he was so keen to promote. Cuts to benefits for one-parent families was one of his first parliamentary moves, from which he was later forced to retreat.

I suspect there are many who, as the crises of our times unfold, find themselves thinking: if only we could hear what Hall has to say. If I now turn to migration and sexual difference, it is because in both cases, as I see it, the parameters of his thinking are so clearly at play, as mobility is confronted by dogmatism in new and disquieting ways. We are living in a moment when, to use Hall’s own words, “a disturbing truth, which seems to arise at the margins of society, somehow floods the mainstream, changing all perceptions as it goes.”

The first of these issues—borders between peoples across land and sea—presses daily on public attention as a flailing UK government, along with other European nation-states, attempts to retrieve credibility and electoral support by tightening the screws. People on “immigration bail” in the UK are to be tracked via fingerprint scanners, criminalizing the whole bunch. Activists have noted—though in fact this clearly has not played even the smallest part in government deliberations—that such a move will be disastrous for those who have been tortured or trafficked.

On the Greek island of Lesbos, twenty-four NGO volunteers went on trial for assisting migrants fleeing the Syrian civil war—another criminalization, this time a “criminalization of solidarity,” which is part of an assault on rescue missions across Europe. Along the borders of Hungary, Croatia, and Romania, defiance of EU law and UN conventions means that migrants are being left to freeze in no-man’s-land. All attempts to create a refugee-sharing mechanism across the European member states have failed.

In the UK, the government repeats its mantra that “illegal migrants” in small boats will be stopped by any means necessary from landing on British shores. When it is pointed out that there is no such thing as an “illegal migrant” under international law, they are redescribed as “irregular,” although what a “regular” migrant would look like is unclear. (In fact the bill is still today referred to as the Illegal Migration Act, which at least presents a wondrous ambiguity about whether it’s the migrants or the bill itself that falls outside the remit of just law.)

This is the border that hardens at the first hint of social anxiety, as those struggling to cross it find themselves scapegoated for disruption inside the nation. Already in 1992 Hall witnessed what he described as “one of the largest forced and unforced mass migrations of recent times,” when

those displaced by the destruction of indigenous economies, the pricing out of crops and the crippling weight of debt, as well as by poverty, drought and warfare, buy a one-way ticket and head across borders to a new life in the west.

(Again, he could be talking about today.) Ten years later he returned to the question as “tens of thousands who can no longer survive at the margins of the system are loosed from their moorings and sent drifting across the world.” They are caught in what he described as the “double helix”—the collapse and entrenchment—of modern nation-states. Migration, he wrote, is the “dark side…the unacknowledged underbelly…of globalization, where everything moves—capital, goods, élites, images, currencies—and only people and labour are supposed to stay put.” Migration then gets blamed for the fact that “unfortunately” things don’t “seem to stand still and be recognisable anymore”—as if they ever were.

The twenty-first-century challenge of global migration “will not be met,” The Guardian wrote in its leading editorial on January 13 this year, “by brutally battening down the hatches”—which does not mean, of course, that many European nations will not continue to try. “Could Europe be a home for some of the homeless and hopeless?” Hall asked, once again with uncanny prescience, twenty years ago. Or, he continued, “as it lowers its frontiers within, is it proving only too effective at raising them, fortress-like, to face the new, straggling armies of the night?” He was referring to the migrants who were “nightly hurling themselves at passing Euro-star trains at the mouth to the Channel.” Faced with such a reality, that image of migrants from the Caribbean pouring out of Paddington Station in 1951 starts to feel like a lost dream.

Illegal or irregular, economic migrants or refugees, black or European (meaning Syrians and Ethiopians and Yemenis pushed back at the border, versus blond, blue-eyed Ukrainians who have been welcomed with open arms)—we are witnessing a politics of definition, where life-and-death decisions are being made on the basis of a single word, and where the state claims a monopoly of meaning, telling people desperate for their lives not only where they are from but also who and what on earth they might be.

Clinching the definitions feels like both a means to an end (reducing the numbers) and an end in itself (a vocabulary of unfreedom in a foreign tongue). I would call this the curse of naming—what Hall, as we have seen, termed the syntax or grammar of politics. In Familiar Stranger, he calls up the famous moment from Frantz Fanon’s writing when he was a young child walking the streets with his mother and another child, white, called out, “Tiens, Mama! Un nègre!” (Look, Mother! A Negro!) The word was enough, a word from which Fanon will never escape. Language must be arrested if we are to hold on to a racist world. (As Hall pointed out, the encounter occurred at the time of Windrush.)

It then follows that the more that race, appealed to as a biological fact justifying inequality and injustice, is exposed as an empty category, as lacking scientific credibility—there are no “pure” races in the world—the more vehemently it is invoked in the vain hope, Hall writes, “that it will bring the argument to a close.” Like sexual difference, race as a category makes its fraudulent appeal to anatomy or physiology to “wind up” the question. One thing is clear: invoking either race or sexual difference as a physiological or moral absolute (often both together) is, to his mind, simply a way of bringing all discussion—including the need to acknowledge that, especially in politics, we are mostly wrong—to a standstill.

The border of sexual difference is at the forefront of the so-called culture wars today, provoking vitriol so toxic that it is indeed effectively shutting down all debate. There is no “seamless category of women,” Hall insisted in 1996. If there is one thing that trans experience has brought irreversibly to the surface, it is surely that the argument about what constitutes sexual difference, like the internal process of uncovering your sexuality, never stops—although you would be forgiven for thinking otherwise when politicians refuse trans people the right to self-define their genders, when certain kinds of health care are banned in the US, when gender surgery is banned in Russia, and when the category of women is presented as an absolute to which trans women have no right to appeal or belong.

As with the refugees being called out as “illegal” or “irregular,” it is the vocative voice—“I will tell you who you are”—that is for me the underlying message of these forms of intolerance and the crime, surely at odds with any political battles being fought in the name of freedom. What also gets lost in these debates is the psychoanalytic insight that we all start with a polymorphous bisexuality and a diffuse eroticism that, at great cost, has to be crunched into shape. Instead, it is claimed that men and women are distinct, from the beginning and forever. The echoes of the fear directed at migrants who threaten the world’s illusory safety by refusing to stand still are unmistakable.

Let us compare that way of thinking with Hall’s appeal for a more flexible, unsettled, and changeable way of thinking and a more transformable world:

Because it is relational, and not essential, can never be finally fixed, but is subject to the constant process of redefinition and appropriation: to the losing of old meanings, and appropriation and collection and contracting of new ones, to the endless process of being constantly resignified, made to mean something different in different cultures, in different historical formations at different moments in time.

Or, in the words of a friend in New York who has recently transitioned from female to male: “I am just so happy to be able to live another life in this life we are living.” I don’t think you can get more open-ended than that. “Another life in this life”—or world—“we are living” must surely today be what we are all aiming for.

This Issue

September 21, 2023

The Life of the Party

Playing with the Past

Why Aren’t Cops Held to Account?

-

*

All terms taken from Hall’s 1995 essay “Parties on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown.” ↩