While our three most recent presidents have little in common as politicians, they do share one critical political skill—the ability to repurpose a pejorative, to take a bit of language deployed by detractors and then turn it to their own ends. Obama managed it with “Obamacare”: today, even in an increasingly red Florida, which leads the nation in Affordable Care Act enrollments, voters hostile to the former president still flock to insurance agencies festooned with familiar “O” logos. Trump did it with “fake news,” a dubiously useful phrase that once described largely Trump-friendly misinformation and now means any coverage he and his supporters find unflattering.

This summer President Biden pulled off a conversion of his own. For months, The Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times had been running pieces disparaging what they called “Bidenomics,” insisting that the administration’s domestic policy agenda had delivered little more to the American people than inflation and wage stagnation. “More Americans are working, but their standard of living isn’t rising,” the Journal’s editorial board wrote in April. “Bidenomics has been a bust for the middle class that Mr. Biden claims to champion.” Then, in a June address in Chicago, Biden seized upon the term “Bidenomics” as a label for all that’s gone right with his economy. “I didn’t name it Bidenomics,” he said, but “it’s a plan that I’m happy to call Bidenomics. And guess what? Bidenomics is working.”

It’s working, Biden has argued, not just in the sense that projects funded by his (foreshortened but respectable) legislative agenda are already underway, but also in the sense that he has managed to bring about a long-overdue break from the trickle-down economics that cut public investment and taxes on the wealthy and corporations. “I know something about big corporations,” he said in Chicago.

There’s more corporations in Delaware incorporated than every other state in the union combined…. I want them to do well, but I’m tired of waiting for the trickle down. It doesn’t come very quickly. Not much trickled down on my dad’s kitchen table growing up.

According to Biden, Bidenomics takes a three-pronged approach to reviving an active role for the federal government in setting the direction of the economy: substantially increasing public investment, involving the federal government more directly in the development of the workforce, and bolstering economic competition. Biden’s signal accomplishments this term belong mostly to the first plank: the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, worth about $550 billion in new federal spending on bridges and broadband; the shrewdly named Inflation Reduction Act, a $750 billion climate, health care, and tax bill in thin disguise; and the rather cloyingly named Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors (CHIPS) and Science Act, which put around $280 billion toward doing exactly what it says on the tin.

The phrase “trickle-down” may be more suited to Biden’s colloquial register, but the economic approach he described and has supposedly laid to rest is, plainly, neoliberalism. In a speech in April, his national security adviser, Jake Sullivan, described that approach as an elite consensus that “championed tax cutting and deregulation, privatization over public action, and trade liberalization as an end in itself.” Similarly, Bidenomics itself has a drier, wonkier counterpart in the phrase “industrial policy,” which has lately caught fire among policy analysts. “Rejecting the idea that the US has operated or can operate on purely free-market principles,” the Roosevelt Institute’s Todd Tucker wrote last fall, proponents of “affirmative industrial policy” insist that the government be active “in resolving questions like which industries rise and fall, how are they structured, and how they produce the goods and services our citizens need.”

There is nothing especially novel about this idea. Republican presidents and politicians since Reagan, for instance, have directed government interventions on behalf of favored sectors of the economy while espousing laissez-faire rhetoric. Giving fossil fuel companies tax breaks is industrial policy of a kind. So are the federal investments that putatively small-government conservatives are happy to make in expanding the military-industrial complex.

Really, federal policymakers have been debating the merits of industrial policy since the early days of the republic. To jump-start the young country’s economy, the Federalist and Whig Parties put protectionist measures and infrastructure investments at the center of their platforms. Rather ironically, they were opposed bitterly in those efforts by the political forces that would eventually form the Democratic Party: Jacksonian populists who strove to convince voters that making the economy work for the working class meant reducing economic centralization and the powers of the federal government.

The Democratic Party’s policy agenda has transformed several times in the nearly two centuries since. And yet the historian Michael Kazin, editor emeritus of the leftist magazine Dissent, argues that the Democrats have sustained a distinct and coherent ideological mission throughout. “The aims and methods of Democrats have evolved,” Kazin writes in What It Took to Win, his recent history of the party.

Advertisement

But one theme has endured: they have insisted that the economy should benefit the ordinary working person, whether farmer or wage earner, and that governments should institute policies to make that possible—and to resist those that did not.

Kazin calls this idea “moral capitalism,” a term coined by the historian Lizabeth Cohen. “A thread of moral capitalism,” he contends,

stretches from Andrew Jackson’s war against the Second Bank of the United States to Grover Cleveland’s attack on the protective tariff, from William Jennings Bryan’s crusade against the “money power” to FDR’s assault on “economic royalists” to the full-employment promise embedded in the Humphrey-Hawkins Act of 1978.

As Kazin tells it, that thread was picked up again by Barack Obama, who in 2011 declared his reelection campaign “a make-or-break moment for the middle class,” then by Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, the party’s principal crusaders against corporate power and inequality. “In all these iterations,” he writes,

moral capitalism would be a system that balanced protection for the rights of Americans to accumulate property, start businesses, and employ people with an abiding concern for the welfare of those with little or modest means who increasingly worked for somebody else.

It favors, he writes elsewhere, “programs designed to make life more prosperous, or at least more secure, for ordinary people.”

“Ordinary people” is, of course, a load-bearing phrase. The party’s historical successes have been built upon radically different visions of who “ordinary people” are and how they ought to be helped. Kazin knows this; he is frank throughout the book about Democratic bigotry and its consequences. This makes it all the more surprising that What It Took to Win reads at times like an invitation to imagine that Obama and Jefferson Davis, whatever their differences, shared a commitment to the same project. “When Democrats restricted their egalitarianism to whites only,” Kazin writes, “they still espoused the ideal, even as they betrayed it in practice.” Might that be because the bare ideal meant as little as it cost to express? All mass parties argue that their principles and economic agendas stand to benefit the masses. No candidate has ever run on a promise to implement immoral capitalism. The devil is always in the details—of policy, yes, but also of the kind of messy coalitional politics Kazin so ably chronicles.

What It Took to Win proceeds in straightforward narrative fashion from the party’s origins in Martin Van Buren’s political machinations through the Civil War and Gilded Age and into the era of the New Deal coalition and its subsequent collapse. Over the course of that history, Kazin argues, the party has embraced a vision of moral capitalism comprising “two different and, at times, competing tendencies.” The first is an animus toward major corporations, the wealthy, and concentrations of elite power. It “envisions a society of small proprietors,” he explains, “or at least of a government that strictly regulates larger ones and often requires them to redistribute part of their wealth, usually through progressive taxation.” The second is support for organized labor, focused on uniting “wage earners and their sympathizers in every region.”

Conceptually, the two traditions aren’t mutually exclusive; progressives today don’t have any trouble demanding in the same breath the expansion of labor rights and higher taxes on the wealthy and corporations. But Kazin contends that the party has tended to emphasize one kind of moral capitalism at the expense of the other. “Historically,” he writes, “which theme Democrats emphasized led them to construct a particular kind of coalition.” For the party’s first hundred years “the anti-monopoly theme was the dominant one.” Then, in the 1930s, it was “largely replaced” by “the pro-labor theme,” which “defined the party’s message” through the 1960s. That shift, Kazin argues, contributed to the gradual softening of labor politics after World War II. Unions tried to secure their place within the Democratic coalition with a tacit agreement not to challenge the dominance of the biggest firms in the booming postwar economy, making “corporate capitalism seem as imperishable as the two-party system itself.”

That may have been so, but the fact that prolabor progressives have more recently begun pushing for action against corporate concentration underscores the trouble with moral capitalism as Kazin presents it. It may be more than just one idea; inarguably, it encompasses more than just two approaches. The Democratic Party’s pursuit of a capitalism that works for “ordinary people”—and the evolution of its perspective on which “ordinary people” matter—has transformed it time and again, not just tactically and not just through shifting emphases on elite power and labor rights.

Advertisement

Kazin’s own account of the party’s history reveals at least four distinct iterations of moral capitalism. The first was white racial populism. For early Democrats, making the economy “moral” for the white common man was a matter of combating not only concentrations of financial wealth but also the federal government. Its powers, they argued, were best limited and confined to securing more land for farmers and settlers through Native genocide and to facilitating the slave trade, which enriched the southern Democratic elites issuing jeremiads against the ill-gotten gains of corrupt and wealthy northerners.

As Kazin recounts, this economic program was sustained during Reconstruction by men like South Carolina’s Benjamin Tillman, a wealthy one-eyed landowner and militiaman who founded the Farmers’ Association, an agrarian populist group that, Kazin writes, “quickly took over most Democratic clubs in the state.” In 1890 Tillman ran for governor and, in Kazin’s words,

ghost-wrote a widely circulated manifesto that attacked the governing elite as a cabal of “aristocrats” who used their money and servile newspapers to prevent any true “champion of the people” from defying their power.

He won the election just as a nascent left, represented by the People’s Party and labor organizations like the National Farmers’ Alliance and Industrial Union, was beginning to make its presence felt in the state. Hoping to retain the support of the farmers who’d brought him to victory, Tillman made appeals to advocates of looser currency and temperance and deployed the rhetoric of white solidarity. In one speech, Kazin notes, he promised to lead lynch mobs against black men accused of raping white women. These appeals worked. He was reelected in 1892, and in the presidential election that year the People’s Party did worse in South Carolina than in any other former Confederate state.

The left had a greater influence on the Democratic Party’s second, more familiar, and more defensible pass at moral capitalism—the progressive movement led by figures like three-time presidential loser William Jennings Bryan, who inveighed loudly against the swelling power of corporations and the wealthy and defended the growing labor movement. Bryan’s “early support for such progressive measures as the direct election of senators, a graduated income tax, public ownership of the railroads, federal insurance for bank deposits, and a more flexible monetary system,” Kazin writes,

enabled Democrats to shift their image from a party that gazed backward toward its antebellum glories to one that allied with many of the reform movements that matured in the early twentieth century—and sought to turn their wishes into law.

Under Woodrow Wilson, who finally broke the party’s presidential losing streak in 1912, the progressive agenda was carried forward with policies including the creation of the Federal Trade Commission and the revival of the federal income and estate taxes—less out of any deep ideological commitment on Wilson’s part than out of a desire to gain and retain the support of Bryan’s allies.

The expansion of the Democratic Party’s ambitions from the second moral capitalism of the Progressive Era to a third iteration of moral capitalism during the New Deal and Great Society eras—with their sweeping government programs, interventions, and experiments—was made possible in no small part by the growing economic and political might of organized labor. FDR was elected in 1932 on promises to fight the Great Depression by leveraging the power of the federal government on behalf of struggling workers, though his Democratic platform made no direct reference to unions. But a wave of organizing after the passage in 1935 of the National Labor Relations Act, which secured the right to union formation and collective bargaining, strengthened organized labor as a political constituency and elicited Roosevelt’s support in rhetoric and in deed. In return, the labor movement, led by an outfit amusingly dubbed Labor’s Non-Partisan League, backed the Democratic Party with thousands of rallies and other mobilization efforts in the 1936 election. Within two years of Roosevelt’s reelection, union membership doubled. And when the Smith-Connally Act, passed over Roosevelt’s veto, banned union contributions in federal elections in 1943, the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) got around it by inventing the political action committee.

The political infrastructure that labor built underpinned what would eventually be called the New Deal coalition: unionized blue-collar workers, minorities, and southerners. But it also catalyzed that coalition’s downfall. Kazin follows the political scientist Eric Schickler and others in showing that the CIO’s activities during the 1930s and 1940s—in particular its insistence on organizing black workers—fueled antilabor sentiment in the South and helped turn the region away from the Democratic Party, well before the backlash against the Civil Rights Acts of the 1950s and 1960s and the GOP’s adoption of the “southern strategy.”

Kazin, like most progressives, argues that the collapse of the New Deal coalition was fatal to the project of making the economy work for working people, and he follows many commentators in characterizing the shrinking and reshaping of the party’s ambitions as a tragic and confused reaction to the rise of the right—a consequence of its failure to develop a coherent and politically galvanizing update to moral capitalism in response to the social and economic crises of the late 1960s and 1970s. “The party as a whole never seriously tried,” Kazin writes. “Instead, most of its leaders, elected and otherwise, either acquiesced to or promoted austere budgeting and market-based solutions, elements of the policy agenda later known as ‘neoliberalism.’” In doing so, he argues, they lost the opportunity “to forge a new coalition of working- and lower-middle-class people of all races who shared, despite their mutual suspicions, a desire for a more egalitarian economic order.”

The trouble with this account is that Democrats did build a winning multiracial, largely working-class political coalition with appeals to a novel vision for a more egalitarian economic order. It was this coalition that brought southerner Bill Clinton presidential victories in 1992 and 1996. Kazin mostly attributes those victories to George H.W. Bush’s “stumbles and misfortunes” and the spoiler candidacies of Ross Perot. But even if one believes that Perot’s candidacies handed Clinton the White House—and it’s not obvious they did—it seems relevant to any evaluation of Clinton’s political record that he remains the last president from either party to have spent most of his time in office with majority approval.

Behind the presidential politics that dominate Kazin’s story, Democratic politicians across the country, from rural communities in the South to the North’s urban centers, spent the last decades of the twentieth century building public support for a policy revolution that rivals the New Deal in scope and enduring impact. A commitment to tax incentives, deregulation, and privatization; paeans to entrepreneurship and technological innovation; an abiding faith in personal responsibility, skill development, and education, preferably through schools engaged in a simulacrum of market competition, as solutions to long-standing structural inequities: understood properly, the Democratic Party’s turn toward neoliberalism wasn’t a rejection of moral capitalism at all. It was another, popular instantiation of it—the fourth.

As the Claremont McKenna historian Lily Geismer argues in Left Behind: The Democrats’ Failed Attempt to Solve Inequality, the party’s neoliberalism was much more than a strategic response to the electoral successes of Ronald Reagan and others on the right. Clinton and other Democratic leaders built a serious, sincere, and expansive policy program, one “based on a genuine belief in the power of the market and private sector to achieve traditional liberal ideals of creating equality, individual choice, and help for people in need.” Out of that belief, the party’s leading figures came to “focus on economic growth and the tools of the private sector rather than on direct government assistance and economic redistribution as the main means to address persistent poverty and structural racism.”

With more fervor than their counterparts on the Reagan right, neoliberal Democrats insisted that businesses could be nudged into productive cooperation with the government for the common good. Jimmy Carter, Gary Hart, and other early advocates spread that message nationally in the late 1970s and 1980s. But the vision would be expanded in state and local policy experiments throughout the Democratic South, including in Clinton’s Arkansas, where struggling and especially minority workers were encouraged to believe, with spotty and mixed results, that making capitalism work for them was nothing more than a matter of gaining access to capital and nurturing an entrepreneurial drive.

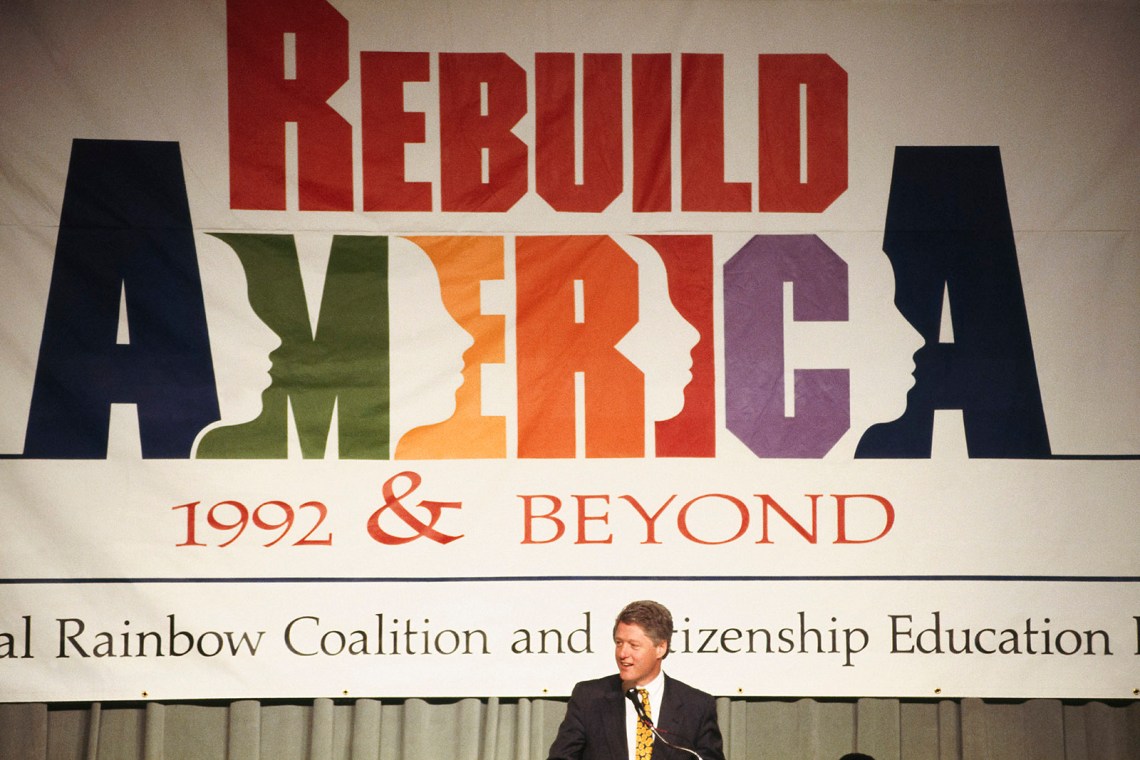

As Clinton began mounting his bid for the presidency in 1992, he carried himself as though he’d discovered the key to the future of his party and the country: a meritocratic ethos that, as an array of cherry-picked success stories suggested, also offered market-friendly solutions to racial inequality. Near the end of the Democratic primaries in June 1992, he made an appearance before Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition to spread the new gospel—a conference address that briefly touched on the riots that had gripped Los Angeles that spring. “One of the most striking things I heard when I was in Los Angeles, three years before the riots and three days after the riots,” he said,

was the unanimous endorsement of community leaders at the grassroots for bold new steps to bring in money from the private sector, public sector, venture capital, small business loans, startup finances. Most people I talked to in Los Angeles didn’t want more big government. They wanted more jobs, and they wanted small business.

This was his segue into a proposal for a “national network of community development banks” that would revitalize struggling neighborhoods by offering “small amounts of money and large amounts of know-how” to budding entrepreneurs with little capital or experience but “a lot of drive and determination.”

And yet struggling minority communities had spent the weeks since the riots, spurred by Rodney King’s savage beating at the hands of city police and the subsequent acquittal of those officers, with much more on their minds than access to small business loans. The rapper and activist Sister Souljah, a panelist on the conference’s previous day, had told The Washington Post the month before that the riots broke the routine, internecine violence that was for so long concentrated in impoverished black neighborhoods. “White people, this government and that mayor were well aware of the fact that black people were dying every day in Los Angeles under gang violence,” she said. “So if you’re a gang member and you would normally be killing somebody, why not kill a white person?”

In what remains one of the most celebrated moments in the history of the modern Democratic Party, Clinton brought up Souljah’s comments and compared her to David Duke at the end of his speech to the Rainbow Coalition. Souljah, he said, had been “filled with the kind of hatred that you do not honor today and tonight.” As jarring as his rebuke might have been, it was of a piece, as Geismer notes, with the policy proposals that preceded it. Clinton hoped to convince white voters that the new Democratic politics would cost them little—both culturally and financially. What minority communities in Los Angeles and across America really needed, he insisted, were the kind of opportunities that had supposedly been delivered successfully in Arkansas: private capital made available to the right minorities, ones who might serve as role models, rather than public funds and programs serving anyone who needed them.

As president, Clinton built this iteration of moral and moralizing capitalism into a new national moral infrastructure, crafted to remold the behavior not of the wealthy and powerful but of the most downwardly mobile Americans: education reform initiatives to foster a competitive drive among teachers and students in struggling communities, work requirements for welfare to fight sloth, prisons that, with the support of most black voters at the time, would punish those who fell through the cracks with increasing severity. If working Americans wanted a greater slice of the economic pie, Clinton insisted, they’d have to fight for it. But not alone—Democratic policy would whip them into shape.

That promise, however, was undermined elsewhere in the Democratic agenda. The enactment of NAFTA at the start of 1994 exacerbated the trend toward deindustrialization that had made a new economic plan necessary in Arkansas to begin with; the deregulation of the financial industry handed working Americans, and minority borrowers in particular, a ticking time bomb. As much good as policies like community development banks and the expansion of the Earned Income Tax Credit might have done, the first decades of this new century offer a plethora of evidence that Clinton’s changes to the American policy landscape made the rich richer and the poorest poorer, and did little to ease the mounting economic pressures on the middle class. “These programs,” Geismer writes,

do not have the capabilities to eradicate the root causes of poverty or comprehensively combat problems of capital disinvestment and structural inequality. Instead, they have all too often provided a means for politicians, philanthropists, and corporations to avoid taking accountability for such problems and [finding] more comprehensive and redistributive solutions.

Clinton’s apologists and heirs are given to describing the party’s turn toward a neoliberal moral capitalism as a shrewd and hard-nosed concession to political realities. For detractors like Kazin, it was a cynical misstep. But Geismer makes a convincing case that Democratic neoliberalism is best understood as a fantasy that was founded on earnest hopes—an economic worldview shaped by a remarkable naiveté about the very forces it attempted to harness.

If it holds, the Democratic Party’s recent turn toward industrial policy may well amount to moral capitalism, take five. At a distance it resembles the third instantiation—that grand stretch from FDR to Johnson—in attitude if not in scale, though this generation of Democrats has no truck with the kind of exclusionary compromises that still mar the New Deal’s legacy. In 1935 the National Labor Relations Act and the Social Security Act infamously omitted the largely black and Latino agricultural and domestic workforces from their provisions and protections. Today, seemingly every economic policy proposal from the party comes appended with an assurance that it stands to benefit minorities in particular; the Biden administration and Democrats in Congress have made subsidizing and supporting the domestic “care economy” a high priority.

In recent months a debate has broken out within Democratic circles and the progressive press over whether the new industrial policy might, in fact, be too accommodating. Liberal pundits have argued that it risks burdening necessary public investments by requiring subsidized projects to satisfy too many progressive commitments, from diversity and equity requirements to stringent environmental standards. Meanwhile, commentators further left have made just about the opposite critique—that the new industrial policy’s social commitments and administrative strictures are essentially window dressing, especially when it comes to labor rights. For instance, union neutrality provisions that Biden once promised would be a condition of federal investment—requiring subsidized firms not to contest votes to organize—were absent from CHIPS, the Inflation Reduction Act, and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

In general, nothing about empowering the state to make critical investments necessarily implies empowering the workers manning those projects or labor at large. Taking this critique seriously could produce yet another moral capitalism, in a guise and policy combination not yet tried. But one can also see in it the seeds of a radical turn, perhaps toward what we might call economic democracy: redistributing at least a meaningful share of the power to control economic investments from company executives, bankers, investors, and public sector technocrats to workers themselves. A turn, in other words, away from capitalism as we’ve known it altogether.

Nothing in Kazin’s history makes it seem especially likely or obvious that Democrats, as buoyed and emboldened by Bidenomics as they might be, will follow their critics on the left down that path. But the party’s future remains, as ever, fascinatingly and frustratingly uncertain. In 1914 the New Republic cofounder Herbert Croly—a progressive and a Republican back when the partisan loyalties of liberal reformers were still contested—likened the Democratic Party to a bacterium. “It can not only subdivide without losing the continuity of its life,” he quipped, “but it can temporarily assume almost any form, any color or any structure without ceasing to recognize itself and without any apparent sacrifice of collective identity.” That mutability all but ensures that the world’s oldest political party will grow much older still.

This Issue

September 21, 2023

Playing with the Past

Why Aren’t Cops Held to Account?