If there’s a star in the climate-driven energy transition, it’s certainly the electric vehicle (EV). The heat pump—the efficient replacement for both furnace and air conditioner—is generally squat and beige; the electric cooktop—the efficient replacement for the gas cooktop that emits greenhouse gases and may be giving your kids asthma—is less glamorous than the glowing Vikings and Wolfs made famous by a hundred sweating chefs engaged in TV battles. But the electric car and the electric truck are at least as sleek and glamorous as their internal combustion forebears. Last year’s Super Bowl was the coming-out party, with commercials for no fewer than eight different EV models from traditional automakers like Ford and BMW as well as lesser-known companies like Polestar.

Joe Biden did much to boost the industry’s future earlier this spring when his Environmental Protection Agency announced new emissions requirements that will more or less force Detroit to build mostly electric vehicles within a decade. But Biden also helped mightily with the best ad from his 2020 presidential campaign, featuring him at the wheel of his 1967 Corvette Stingray. “I like to drive; I used to think I was a pretty good driver,” he says before peeling out. When he stops, he gives viewers a tour of the car, under the hood and behind the wheel. “This is iconic industry,” he says. “How can American-made vehicles no longer be out there? I believe that we can own the twenty-first-century market again by moving to electric vehicles.” His plan seems to be working: the latest estimate from Bloomberg is that more than half of cars sold in this country in 2030 will be electric.

But the rush to electric vehicles has met with some powerful criticisms. The batteries that keep those machines speeding along need, for example, lithium, and researchers like Thea Riofrancos, a political scientist at Providence College in Rhode Island, have made persuasive arguments against the mining that will be required; as she points out, if we drove smaller cars we’d need less lithium, and many others have begun to work on reducing the human and environmental costs of all that extraction.

A transition this big can’t help but raise deeper questions about the automobile’s place in the world. Might not this moment, when climate science makes it clear that we need to give up on gasoline, also be the right time for a reappraisal of our love affair with the car? A few places—Paris perhaps most notably, but also Brussels and even Tucson—have used the pandemic as an opportunity to move aggressively toward a metropolis based on buses and bikes.

The two books under review here remind us that it’s not just the car that’s caused havoc, but also the two things that it absolutely requires: roads and parking spaces. The car has reconfigured the planet, with its carbon emissions melting the poles and raising sea levels. But it has also reconfigured almost every place on the planet as we have remade our landscape to accommodate its needs.

Ben Goldfarb, a writer I have known and followed for many years, won the 2019 PEN/E.O. Wilson Literary Science Writing Award for his first book, Eager: The Surprising, Secret Life of Beavers and Why They Matter. He makes a good case for the salutary effect that beavers, and especially their dams, have on our landscape; the book could be read as a tribute to small-scale and carefully sited engineering projects.

That’s not how you would describe the network of roads that humans have laid out—40 million miles across the earth, “from the continent-spanning Pan-American Highway to the hundred thousand miles of illegal logging routes” that slice through the Amazon. As Goldfarb writes in his new book, Crossings: How Road Ecology Is Shaping the Future of Our Planet, “when alien archaeologists exhume the rubble of human civilization, they may conclude that our raison d’être was building roads.” There are many reasons for humans to doubt this was a good idea, but Goldfarb’s focus in his wide-ranging and absorbing account is the effects on the rest of creation:

To us, roads are so mundane they’re practically invisible; to wildlife, they’re utterly alien. Other species perceive the world through senses we cannot fathom and experience stressors and enticements we hardly register. Bats are lured astray by streetlights, snails desiccate as they slog across deserts of asphalt, and seabirds crash-land on the shiny tarmac they mistake for the ocean. Consider the sensory experience of, say, a fox approaching a highway; the eerie linear clearing that gashes the landscape, the acrid stench of tar and blood, the blinding lights staring from the faces of thundering predators.

It turns out that almost since the Model T, biologists and other observers have been tallying the roadkill that cars have produced. As they have sped up and roads have improved, the carnage has grown: “The better the road, the bloodier.” If a car is driving below thirty-five miles per hour, few animals are struck; above sixty and the road turns into a killing ground. By 1995 deer were a factor in more than a million crashes a year, with two hundred human fatalities—making this gentle creature “North America’s most dangerous wild animal.”

Advertisement

Even when animals aren’t killed on roads, they’re often unable to migrate to the habitat they need on the other side. Practitioners of the new science of “road ecology” provide this rule of thumb: “Roads with more than 10,000 vehicles per day should be considered absolute barriers to most wildlife.” Road engineers, faced with this problem and the high costs that crashes impose on travelers, insurance companies, and local governments, have tried a variety of approaches. Fences don’t do much—animals find holes or follow them to the end and then die crossing. The earliest wildlife underpasses built beneath highways didn’t work either. The first ones in Wyoming, more than sixty years ago, were “ten feet wide, ten feet high, and several hundred feet long—dark, echoey crypts that could backdrop an ungulate horror movie.”

Over the years, trial and error showed that fences paired with underpasses that are short and wide enough to let animals see the other side could be effective. Even better (if pricier) are overpasses, such as the one in Banff National Park, in the Canadian province of Alberta. The Trans-Canada Highway—4,860 miles long—was built in the region in the 1950s, and “by the 1970s so many animals were dying on the Trans-Canada that conservationists called it the Meatmaker.” The usual prescription of fences and underpasses did reduce elk mortality, but grizzly bears—shier animals used to forest cover—stayed away. In the 1990s engineers started building wildlife overpasses with bushes and trees, and after a few years motion-detection cameras showed bears teaching their cubs how to cross.

In Goldfarb’s travels around the country and the world, he finds places—including on the vast network of logging roads operated by the US Forest Service—where authorities are decommissioning old and little-used roads. (Though this has become a part of the culture war: in Utah particularly, local politicians have crusaded to keep all roads open, no matter how disused and out of repair.) The sole road in Denali National Park is now open only to buses carrying tourists, in part to reduce the noise of cars. (EVs will be scant help here—above thirty-five miles per hour, it turns out, tires produce more noise than engines.) In the Upper Midwest, milkweed is being planted along roadsides to feed monarch butterfly caterpillars. In a Brazilian reserve, Goldfarb saw engineers building a “Rodovia Sinuosa” designed to slow traffic, “its bed rising and falling in waves, like a gentle roller coaster.”

But that Brazilian innovation, of course, is overshadowed by the ongoing attempt to punch ever more roads into the nation’s trackless forest, which damages wildlife and also the indigenous people of the Amazon. “The story of the rainforest’s unraveling is that of its highways, the ‘lines of penetration’ through which logs poured out and agriculture flooded in,” Goldfarb writes. Ecosystems “fell into disarray,” and so did civilizations, as “pathogens overwhelmed Indigenous immune systems. Within a year of the Trans-Amazonian’s construction, nearly half the population of a tribe called the Parakanã had perished.” Goldfarb continues, “As the world trickled in” along these new pathways, “Indigenous languages and customs were flattened by cultural bombardment. Anthropologists have found that linguistic diversity is lowest where South American road density is highest.”

Goldfarb rather brilliantly connects that easy to acknowledge Amazonian damage to the less well documented effects of roads on poor and vulnerable communities in our own country. He points out that one result of the federal government’s racist redlining policies in the early decades of the twentieth century was systematic underinvestment in Black communities and the creation of what came to be called “blighted” neighborhoods. And then in the postwar years, federal, state, and city governments used highway policy in turn to eradicate those neighborhoods: “If Black neighborhoods were nails, freeways were a convenient hammer…. General Motors, for one, proposed using freeways to displace ‘undesirable slum areas.’”

The construction of the interstate highway system, begun in the Eisenhower years, became “the erasers with which cities rubbed out Black communities and the walls with which they partitioned them from white ones.” In St. Paul, I-94 wrecked Rondo, a thriving middle-class Black neighborhood; Miami’s I-95 “drove out thirty thousand residents of Overtown, a cultural hub known as the Harlem of the South.” Moreover, Goldfarb writes,

Advertisement

Interstate 85’s course through Montgomery was plotted by Alabama’s “foremost segregation leader,” who plowed the freeway through the neighborhood of Oak Park to punish the civil rights leaders who called it home.

The destruction continues to this day, because living next to the highways that wrecked communities now wrecks bodies. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Black people are 40 percent more likely to live near a highway than whites, and Latinos 60 percent more likely; as a result,

the noxious by-products of internal combustion—sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, volatile organic compounds, and the vile gunk known as diesel particulate matter—are inordinately absorbed by Black and brown bodies.

Goldfarb grew up in Westchester County, and he notes that in the Bronx—divided by three expressways to ease the commutes of suburbanites—“residents are three times more likely to die of asthma than the national average.” He focuses, though, on another New York city, Syracuse, where the construction of I-81 in the 1960s destroyed the tight-knit but redlined Fifteenth Ward, bringing with it all the usual pollution and social disintegration. Now, finally, some of the damage may be undone; the elevated highway has started to corrode, and after much deliberation the state government has decided to replace it with “a radical urban overhaul,” a “street-level boulevard, graced with sidewalks and bike lanes and storefronts, that one advocate called the ‘Champs-Elysees of Central New York.’” Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg said that it was a chance to “learn from our past and do it better.”

In the course of his reporting trips to Syracuse, Goldfarb settled on one word to describe what planners were aiming for as they tried to take down freeways and rebuild actual communities: “connectivity…. Road ecologists and urban advocates are engaged in the same epic project: creating a world that’s amenable to feet.”

Henry Grabar settles more fully into this urban story in Paved Paradise: How Parking Explains the World. (Subtitle notwithstanding, it’s focused almost completely on the US.) Grabar, a staff writer at Slate, has been a finalist for the Livingston Award, given for excellence in reporting by journalists under thirty-five. He deserves it: the reporting in this book is rich and deep. It’s undermined slightly by an uncertain structure that an editor should have fixed. (In my mind’s eye, there is some charismatic guru roaming America’s MFA programs and advising young writers that chronological order is beneath them.) Nonetheless, readers will emerge from this book aware that a series of bad policy reactions to the advent of the automobile helps explain much about today’s landscape.

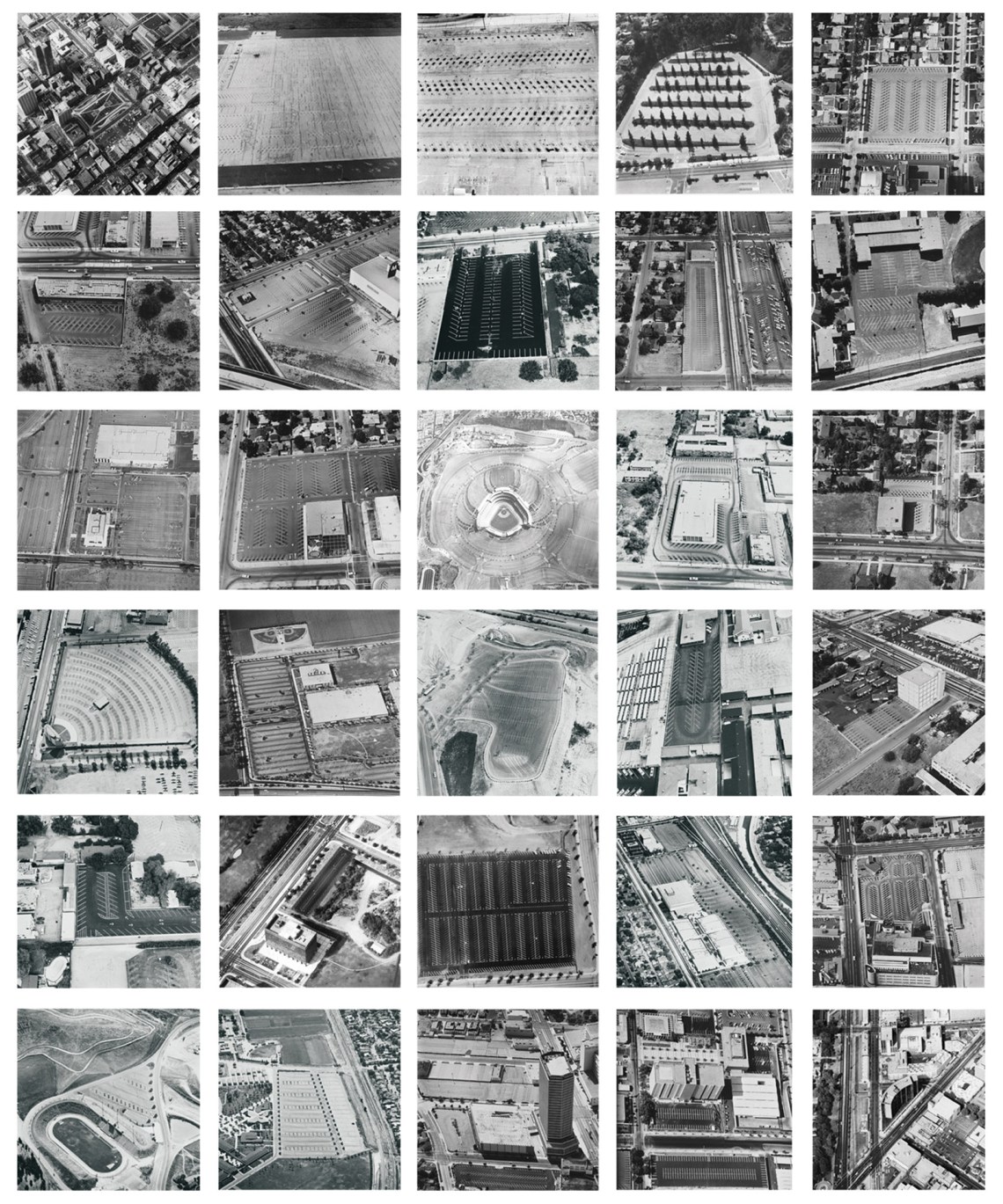

As suburbs began to flourish, and in particular as the shopping mall emerged as a threat to downtown retail districts in the 1950s, city centers reacted by trying to increase the amount of parking; before long, parking lots had replaced much of what had made those downtowns attractive. According to Grabar, Phoenix now has 12.2 million parking spaces, or three per person; Des Moines has twenty parking spaces per household. Little Rock, Newport News, Buffalo, and Topeka devote more land to parking lots than to buildings. By square footage, there is more housing for each car in the US than there is housing for each person.

This devotion to the storage of automobiles comes with many costs—Grabar dutifully summarizes the research about, for example, the effects of runoff from impervious surfaces after rainstorms. And it comes as well with many fascinating stories—for instance, of how Chicago leased all its parking meters to a group headed by Morgan Stanley for seventy-five years and now must pay the investment bank for lost revenue whenever the city, say, wants to close off a street for a music festival. But Paved Paradise is fundamentally an account of how the requirement of a certain number of parking spaces per occupant has distorted building patterns across the country.

These “parking minimums,” which came into effect in the postwar years, mandated that developers build a stupendous amount of parking spots. In Detroit, the building code requires “one off-street parking space” for every “tumbling apparatus” at a gymnastic center, pool table in a pool hall, and four seats in a theater, not to mention for every hundred square feet in a substance abuse facility, beauty shop, or golf course clubhouse. These codes are everywhere: Grabar quotes a planner in Corvallis, Oregon, who explains that because the town had expanded its community center, it was forced to pave over a baseball field to create more parking. Shopping centers are instructed to size their parking lots based on retail traffic on the Saturday before Christmas. The 1985 Parking Generation Manual, supplied by the Institute of Transportation Engineers, was

where America’s bad parking ideas were codified and disseminated. The book of parking requirements is long and boring, but the premise is simple: every type of building creates car trips, and projects should be approved, streets designed, and parking constructed according to the science of trip generation.

In 2005 the UCLA economist David Shoup published a 733-page book called The High Cost of Free Parking, which led to the emergence of a growing band of antiparking evangelists who are beginning to win important battles. Shoup’s central insight is that we all pay for supposedly free or low-cost parking. It’s just that the cost is hidden, in Grabar’s words,

in the rent, in the check at the restaurant…. It was hidden on your receipt from Foot Locker and buried in your local tax bill. You paid for parking with every breath of dirty air, in the flood damage from the rain that ran off the fields of asphalt, in the higher electricity bills from running an air conditioner through the urban heat-island effect.

All this amounts to a subsidy to drivers in the hundreds of billions of dollars.

If cities charged appropriately for currently free or cheap parking, almost everyone would benefit. Shoup’s UCLA grad students roamed the nearby Westwood section of Los Angeles, where street parking was mostly free and where parking garages were fairly expensive; as a result, at the peak hour of demand, 96 percent of curb spots were occupied and 1,200 garage spaces were vacant: “This single neighborhood, with its fifteen blocks of 470 underpriced meters, was generating 3,600 extra miles of…driving every single day.” When cities like San Francisco began adjusting their meters, “curbs opened [and] garages filled…. Price changes reduced the time San Franciscans spent looking for parking by 43 to 50 percent in pilot areas.” Double-parking dropped by 22 percent, and “the total amount of driving in the pilot areas fell by 30 percent.”

But parking policy didn’t just distort the driving experience; it fundamentally shifted what and where developers built. If you want to understand fast-food outlets and big-box stores, think for a moment about what kind of architecture parking minimums essentially mandate. Grabar joined a Los Angeles lawyer named Mark Vallianatos for what he called a “Forbidden City” tour of Angeleno neighborhoods: the “familiar houses and apartment blocks of neighborhoods like Hollywood, Koreatown, and Mid-City,” the duplexes and triplexes, the “Hollywood apartment towers, with their schlocky appropriations of French châteaus or Chinese pagodas,” “elegant, Bauhaus-inspired midrise apartment buildings,” all the “glamorous and the mundane, essential” buildings. And all of it would now be illegal, because none of these buildings came with enough parking spaces to meet current requirements. Los Angeles, as Grabar notes, had “banned itself.”

And all across America, that’s what happened—you could build Walmarts and you could build “high-density, high-value properties like offices, hotels, malls, and condos that could afford to build structured (or even subterranean) parking garages.” But nothing in between:

Parking requirements helped trigger an extinction-level event for bite-sized, infill apartment buildings like row houses, brownstones, and triple-deckers; the production of buildings with two to four units fell more than 90 percent between 1971 and 2021.

When Los Angeles lifted the parking-minimum requirements in its failing downtown at the turn of the twenty-first century, developers responded. “One vacant building after another was reborn as apartments,” Grabar writes. “New residents supported little businesses downstairs, like video stores and restaurants.” And these neighborhoods are nicer, “precisely because they offer access to places where car ownership is optional.”

With the backing of pro-housing activists, new urbanist architects, preservationists who want to see old buildings find second lives, leftists “enraged by the hurdles to low-income housing,” and rightists angry at “laws that told you what to do with your property with dubious justification,” the movement against parking spaces is beginning to change America’s building codes. It won’t be easy—some jurisdictions have clearly used parking requirements to keep out low-income and racially mixed housing. And—culture wars again—some on the right have decided that calls for a “fifteen-minute city,” where residents can find all they need within an easy walk, are part of a George Soros–led globalist conspiracy.

But the trend lines are moving in the right direction. Manhattan’s temporary plazas in places like the Flatiron district and Times Square have proved hugely popular; the pandemic helped people see that there were far better uses for the curb than storing cars. In Paris, the remarkable mayor Anne Hidalgo has added new bike paths and bus lanes, and she plans to get rid of half the curbside parking—70,000 spaces—by 2025.

And so we return to the question with which we began: How swiftly can we end the reign of the car?

Changes in city-center parking regulations aren’t a panacea for a century of bad development; among other things, as poorer people are displaced to suburbs, they become more car-dependent. And those suburbs—where most Americans of all classes live—are so doggedly designed around the car that it’s hard to imagine them shifting very fast. Progress is underway. In greater Boston, for instance, suburbs served by the MBTA mass transit system are now required to figure out how to build multifamily housing alongside the driveway-and-backyard manors. And there are some game-changing technologies emerging: the e-bike, for instance, is already helping to transform some of our ideas about mobility.

But it will take a while: almost 90 percent of passenger miles traveled in America are in cars and trucks. So you could double or triple the number of people on bikes and in buses and they would still be a minority. Dealing with the imperative of climate change likely demands a generation or two of electric vehicles, but hopefully their somewhat lower range, even with all the charging stations now under construction, will serve as an asset more than a drawback, by helping reorient people to more localized travel. Someday in the not impossibly distant future, if we manage to prevent a global warming catastrophe, you could imagine a post-auto world where bikes and buses and trains are ever more important, as seems to be happening in Europe at the moment.

You can sense the possibilities at the end of Goldfarb’s book, an account of a visit to the newly constructed wildlife overpass in the wilderness alongside I-90 at Snoqualmie Pass, in Washington State, where he saw nursery-grown seedlings—“snowberry, wild rose, maple”—that had taken root and whole herds of elk, “cows nursing calves and bulls jousting as trucks hurtled beneath them.” Goldfarb imagines the tree canopy on the bridge thickening,

firs scraping the sky. The black bear padding through in fall, bound for a den in the volcanic debris of a distant mountain…. Lives not on the road but over and beyond it, a road that animals would never meet, a road the land would never notice.

This Issue

October 5, 2023

Ukraine’s New Normal

Storyboards and Solidarity