The cavalcade of exhibitions marking the fiftieth anniversary of Pablo Picasso’s death in 1973 isn’t going to return him to the exalted position he long held as visionary, truth-teller, and troublemaker. It’s not only that some observers believe that the Spanish artist—dismissed now as an elitist, a sexist, a sadist, or merely one artist among a great many others—never deserved that lofty reputation. It’s also that the idea that any creative individual can almost single-handedly define the ambitions, ideas, and ideals of an era has been abandoned. Some say good-bye and good riddance—let a thousand flowers bloom. But this hasn’t happened. Picasso, a titan among the makers and shapers of modernity, has been eclipsed by a very different vision of the visual arts, with Andy Warhol now the defining figure for several generations that conceive of art as appropriation and replication. Warhol mocked and effectively dismissed the idea of the visionary genius embodied in figures as diverse as Picasso, James Joyce, Igor Stravinsky, and Virginia Woolf with the quip that “in the future everybody will be famous for fifteen minutes.” But Warhol’s fame—thirty-six years after his death—is only rising.

That is not to say that Picasso is no longer a figure to be reckoned with. This fall New York is hosting a few beautifully focused exhibitions, the most prominent of which are “Picasso: A Cubist Commission in Brooklyn” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and “Picasso in Fontainebleau” at the Museum of Modern Art. To some, the scrupulous art-historical and museological scholarship that these exhibitions represent may seem old-fashioned—an elitist throwback—at least when compared with the pizzazz of “It’s Pablo-Matic: Picasso According to Hannah Gadsby,” the show that the Australian comedian organized at the Brooklyn Museum. Gadsby set works by Picasso within a feminist critique that began with a blast of posters and broadsides produced by the Guerrilla Girls in the 1980s and 1990s.

The focus of “It’s Pablo-Matic,” which isn’t on Picasso’s achievement but on Picasso as a cultural phenomenon, points to what I would call the Warholization of Picasso—a process that in ways both subtle and not so subtle has dramatically altered our understanding of the artist, his work, and his place in the world. I feel the same process at play in the opening line of Looking at Picasso, a new overview of his career by the respected art historian Pepe Karmel. “Picasso,” Karmel announces, “looks like a movie star in his 1919 Self-Portrait.” The only reason to refer to the undeniably good-looking fellow in this drawing as a movie star is to Warholize him—to suggest that Picasso has some of the aura that Troy Donahue or Warren Beatty has in Warhol’s paintings from the 1960s.

The shift that I’m referring to—Picasso out and Warhol in—began a generation ago in the 1980s at no less an institution than the Museum of Modern Art, where Picasso had by many estimates been the dominant figure since the late 1930s. In 1980, seven years after his death, MoMA said good-bye with a retrospective that filled the entire museum. Then, in 1989, two years after Warhol’s death, MoMA embraced the new dispensation with a retrospective that filled two floors and was, The New York Times reported, “the most ambitious solo show at the Modern since the Picasso retrospective in 1980. The scale is not so much a canonization as a recognition that the canonization has already taken place.” The catalog of “Andy Warhol: A Retrospective” may well have been designed as a new reference book for a new age; it had the same massive dimensions as the catalog of “Pablo Picasso: A Retrospective.” The essays in the Warhol catalog were spritzed with comparisons between the two men. “Warhol,” the art historian Robert Rosenblum opined, “may end up rivaling Picasso himself in providing to all comers the most daunting breadth of approaches.”

Rosenblum wasn’t wrong. Blake Gopnik, at the conclusion of Warhol, his huge biography published in 2020, declares that “it’s looking more and more like Warhol has overtaken Picasso as the most important and influential artist of the twentieth century.” What exactly Gopnik means by this remains unclear. Is he simply saying that Warhol now receives more attention than any other artist? Or is he making a statement about artistic evolution and succession, arguing that just as Picasso’s innovations at some point may have become more important and influential than Cézanne’s, so Warhol’s contributions, such as they are, have rendered Picasso’s less important, less influential?

Whatever Gopnik is trying to say—I suspect it’s a bit of both—Warhol’s sky-high status now has an aura of historical inevitability, as if the brute facts (exhibitions, sales, attention) are what really matter, and whatever one thinks about the intricacies of artistic practice and philosophy is of secondary importance. Warhol’s supporters are inclined to go further. From the brute facts they derive aesthetic arguments. Because he’s outrageously famous, it follows that he’s profoundly original. That is what aesthetics come down to in the Age of Warhol.

Advertisement

This line of thought, embraced by art critics and historians since around the time of the MoMA retrospective, has now reached the United States Supreme Court, in the form of Justice Elena Kagan’s long dissenting opinion in Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts v. Goldsmith, which was decided in May. At the core of all artistic activity there is an act of transformation, and by Kagan’s lights one of the great masters of transformation is Warhol, a figure she compares to a couple of the masters of the Italian Renaissance. The confidence with which Kagan makes her argument, a layman’s assertions bolstered by a half-century of art criticism and art history, only demonstrates how horribly debased the general understanding of artistic processes has become in recent years. A generation ago members of the educated public may have found themselves daunted by the fractured forms of Picasso’s Cubism—or the babel of language in Joyce’s Finnegans Wake or the astringencies of Stravinsky’s Agon—but they accepted the titanic transformations those works involved as a challenge to be explored, debated, approached with a healthy skepticism. For Kagan and other members of the educated public there may be some relief in the immediacy of Warhol’s effects, which a museumgoer can grasp without thought, reflection, or struggle of any kind. After Warhol, confronting Picasso’s enigmas may seem as retro as taking a car trip without GPS.

Kagan, joined by Chief Justice John Roberts, obviously believed that she was taking the high road in this case, which involved a photograph by Lynn Goldsmith of the musician Prince that Warhol used as the basis for a series of works, one of which landed on the cover of a special edition Condé Nast magazine without Goldsmith receiving any acknowledgment or payment. The issue before the Court was what is known as fair use. Had Warhol altered Goldsmith’s photograph to such an extent that he came up with an entirely independent work of art? In which case Goldsmith would have been unable to claim protection for her photograph under the copyright laws. I have no interest in engaging with the complex questions that surround fair use and copyright, except to say that these are questions that have involved court dates for a number of artists—including Richard Prince and Jeff Koons—who have followed Warhol’s lead in their wholesale appropriation of other people’s images. What does interest me here is the eagerness with which Kagan has chosen to speak on behalf of Warhol, not only as a judge but, ex officio one might say, for the sophisticated museumgoing public.

What Kagan salutes as “the dazzling creativity evident in the Prince portrait” amounts to nothing more than the recropping of a photograph and the replacement of the modulated grays of the original with some bright, hard-edged color shapes. She’s on firm ground when she asserts that there is “expert evidence” to support her assertion. But Kagan isn’t content to demonstrate that some sort of artistic process has taken place. She wants to make sure that Warhol has a place in the Great Tradition. She complains that the majority, by concluding that Warhol has indeed infringed on Goldsmith’s copyright, “stymies and suppresses that [transformative] process, in art and every other kind of creative endeavor.” She’s not making an argument for Warhol as some sort of modernist or postmodernist. She’s saying that he does what all the great artists have done. She compares him with Giorgione, Titian, and Manet, artists who “engaged with a prior work to create new expression and add new value,” as if that were what Warhol was doing when he slapped some bright colors on a photograph of Prince. Wasn’t there anybody around the Supreme Court willing to warn Kagan that she risked absurdity when she mentioned Giorgione and Titian in the same pages as Warhol?

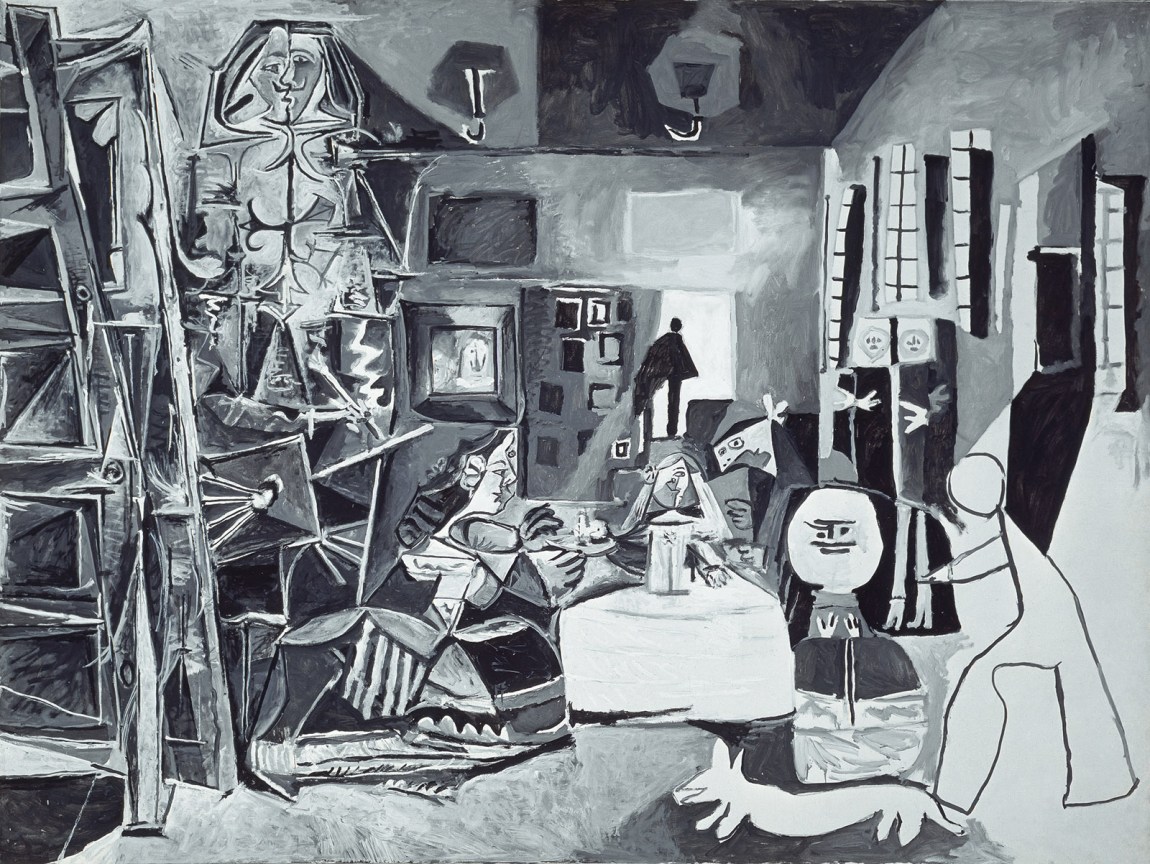

Warhol was up to something with the Goldsmith photograph, but what was involved was an operation, not a transformation. To grasp the critical difference there is no better figure to turn to than Picasso, who in the mid-1950s, only a few years before Warhol began making his paintings of Campbell’s soup cans, dollar bills, and movie stars, confronted the old masters with two groups of paintings. The variations that Picasso produced on Delacroix’s Women of Algiers in 1954–1955 and Velázquez’s Las Meninas in 1957 may not be among his very greatest works, but they are among the twentieth century’s greatest examinations of the possibilities and perils of artistic transformation. In her memoir Picasso Plain, his friend Hélène Parmelin recalls staying with the artist and Jacqueline Roque, soon to be his second wife, while he was working on the Velázquez variations. In a chapter entitled “The Battle of Las Meninas,” she records Picasso’s struggles to wrest something of his own from a seventeenth-century masterwork, and writes that those struggles involved what she refers to as the “grammar of construction.”

Advertisement

The “grammar of construction”—which Parmelin mentions almost causally, as if it were something everybody takes for granted—is essential to understanding the difference between an operation and a transformation. The grammar of any art—whether visual, literary, or musical—is a system of signs, symbols, and relationships that is always subject to reshaping and renewal. Picasso was aiming to explore and maybe even reconceive Velázquez’s approach to pictorial grammar when he turned his attention to Las Meninas; over a period of four months he produced almost five dozen meditations on it.

Las Meninas is a house of mirrors of a painting, and Picasso in the first and largest of his variations magnifies the mirror—at least certain aspects of it. Velázquez painted himself in the process of painting Philip IV and his queen, Maria Anna of Austria (who are seen in a mirror), while the king’s daughter, the Infanta Margarita Teresa, and her entourage take center stage, simultaneously subjects and spectators, seeing and being seen. Picasso—by recalibrating lights and darks and foreground and middle ground, which are among the rudiments of a painter’s grammar—shifts the focus from the infanta to the artist himself. But he refuses to leave it at that. He utterly transforms the figure of the painter, whom Velázquez conceived as a dark, sobering sight, into an explosion of sharp edges and shifting shapes that reaches from the bottom to the top of the canvas. Picasso’s slashing chiaroscuro, which suggests a grammatical extension of Velázquez’s painterly touch, climbs higher and higher, until the seventeenth-century master becomes a saturnine jack-in-the-box lording it over the royal family. Picasso is telling us that the artist is king.

Picasso is always navigating between a then, what he knows of earlier art and culture, and a now, his own moment. There was hardly a time or a place—ancient Greece and Rome, seventeenth-century Spain and the Netherlands, the brothels of nineteenth-century Paris and Tokyo, the icons and idols of Africa and the South Seas—that didn’t engage him and embolden him, but everything he touched he reconceived. In “Picasso and the Spanish Classics,” a small show this fall at the Hispanic Society Museum and Library, organized by Patrick Lenaghan, we see him focusing on a collection of the lyrics of the Spanish Baroque poet Luis de Góngora, for which he produced a series of prints. In his portrait of the poet Picasso stays close to the dramatic naturalism that Velázquez adopted for his own portrait of him, while to accompany the sonnets he time-travels, reimagining Góngora’s beloved as a woman of his own time and place. Perhaps most extraordinary are Picasso’s renderings of the poems in his own calligraphic hand. In the show, where his calligraphy is juxtaposed with examples of seventeenth-century handwriting, we see how he channeled the earlier script and in the process reimagined it as a modern expressionist graphic art. Picasso dug deep into an earlier visual language and found himself speaking it with new accents and new implications.

Warhol’s supporters, perhaps arguing that he rejected the grammar of construction as hopelessly old-fashioned, will say that he was responding to everything that was artificial, dissociated, impersonal in our world. Kagan is suggesting something along these lines when she salutes Warhol’s “commentary on celebrity culture.” Richard Meyer, an art historian at Stanford University, backing up Kagan in an op-ed in The New York Times, observed that “Warhol’s slightly off kilter, Day-Glo brilliant pictures change the way we look at celebrity and consumer culture. His work, at its best, transforms us.”*

I’m not sure where to begin. By shifting the transformative process from the artist to the audience, Meyer may feel that he’s broadening our perspective on Warhol; what counts isn’t so much the quality of his imagination as his impact as a provocateur. But even if we accept that Warhol is a provocateur, isn’t it naive to imagine that he’s telling us much that we didn’t already know? Warhol’s admirers believe that he’s bringing out the ironic undercurrents of popular culture when he produces repetitious, revved-up images of Marilyn Monroe, Elizabeth Taylor, and Troy Donahue. But haven’t we always known that the appeal of the Hollywood stars is layered, paradoxical, complex? They’re doubles—both individuals and icons.

Monroe’s greatness has everything to do with the comic complexity—the shadings and ironies—that she brought to her natural beauty. Does anybody who’s watched Gentlemen Prefer Blondes or Some Like It Hot think that Monroe didn’t know what she was up to? Warhol understood her genius. In his best early paintings he underscored it, bringing an easygoing wit to some of his Marilyns. But those who claim that Warhol brings fresh insights to our experience of celebrity are underestimating how layered the appeal of popular culture has always been. The Americans who flocked to see Merle Oberon and Laurence Olivier in Wuthering Heights in 1939 had no trouble understanding that these stars were simultaneously acting their roles in a nineteenth-century drama and winking at the audience, playing at stardom and sex appeal and all the rest of it in the present.

Anyone wondering what an artistic transformation really looks like need go no farther than the two major Picasso exhibitions mounted in New York this fall. “Picasso: A Cubist Commission in Brooklyn” focuses on the early days of Cubism, by many accounts the most thoroughgoing transformation of the grammar of painting since the beginnings of the Renaissance. “Picasso in Fontainebleau” zeroes in on the artist in the summer of 1921, when he was investigating more traditional pictorial grammars. Museumgoers who take in these two exhibitions and then turn to Warhol—whether his early Marilyns or his later regurgitations of Leonardo’s Last Supper, some with an overlay of camouflage patterning—will find themselves facing an intellectual and artistic desert.

The Metropolitan show explores a site-specific project that Picasso began but never completed; it has remained something of a mystery, challenging the efforts of formidable scholars, including William Rubin and John Richardson, to determine what the commission actually involved, exactly what Picasso had in mind, and how much of the work was completed. Hamilton Easter Field, an American painter whose prosperous family owned a large house in Brooklyn Heights, moved in some bohemian circles in Paris in the years before World War I. It was probably in 1909 that he commissioned from Picasso a series of paintings to decorate the library of the house at 106 Columbia Heights, apparently eager to see how Picasso’s fractured forms and kaleidoscopic arabesques would look as domestic décor.

Anna Jozefacka and Lauren Rosati, in association with the Leonard A. Lauder Research Center for Modern Art at the Metropolitan, have done some exemplary research. They’ve brought an unprecedented level of detail and clarity to their discussion of what the room for which the paintings were intended looked like and where they might have hung. And they’ve brought together for the first time six paintings associated with the project. What seems clear is that at least for a time Picasso was eager to see if the Cubist syntax that he and Braque were developing, cast in the somewhat larger dimensions and exaggerated vertical and horizontal formats the commission demanded, would bring new shades of lyricism and mystery to centuries-old traditions of mural painting.

In the major Cubist works that may have been intended for Brooklyn Heights—they include Reclining Woman on a Sofa (1910), Pipe Rack and Still Life on a Table (1911–1912), and Still Life on a Piano (1911–1912; see illustration at beginning of article)—the lights, darks, volumes, and voids essential to the grammar of European painting since the Renaissance are recapitulated but transformed so completely as to force us to see everything anew. The handle of a cup, the keyboard of a piano, and the bend of a woman’s leg emerge unexpectedly from the jagged chiaroscuro, giving old realities a new allegorical power. The quotidian is interrogated but not quite abandoned; in one instance the letters “CORT” (they probably refer to the pianist Alfred Cortot) are stenciled onto the canvas, thereby reasserting a literalism that the painter’s speculative spirit threatens to obliterate. Never have materiality and immateriality confronted each other with more poetic brinksmanship than in the paintings that Picasso and Braque were making in the years leading up to World War I. The known world dissolves, but the palpability of our experience remains, restored through dramatic brushstrokes that echo the painterly sfumato of Corot and even Rembrandt. Picasso risks shredding art’s grammar but pulls back, the language shaken but intact.

“Picasso in Fontainebleau,” curated by Anne Umland, focuses on work done a decade after the paintings in the Metropolitan show. Picasso was still pursuing the discoveries of the Cubist years but now pushing them in divergent directions. In certain paintings, including MoMA’s Three Musicians and the version of the same composition from the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Cubism’s atmospheric grisaille is abandoned in favor of hard-edged, clearly colored elements from which Picasso forms the three musicians, as striking as heraldic devices, who many believe represent him and two great poet friends, Guillaume Apollinaire and Max Jacob. In other works, including MoMA’s Three Women at the Spring and a version of that composition from the Musée Picasso in Paris, the Cubist monochrome remains, now reimagined with a pre-Cubist solidity to create a neoclassical monumentality.

The Château of Fontainebleau, in the town not far from Paris where Picasso spent the summer of 1921 and made all these paintings, had become in the sixteenth century under Francis I a creative center where Italian and French artists and craftsmen forged new variations on the Greco-Roman tradition. Picasso was emboldened by what he saw and more generally by the history that Fontainebleau represented. The two versions of Three Musicians and of Three Women at the Spring, however radically different Picasso’s treatment of the twelve figures they include, are all variations on closely related themes: the trio or threesome as a kind of community; the monumentality of foursquare figures enclosed in a foursquare space; the concreteness of sharp-edged flat color shapes versus the concreteness of clearly delineated volumes.

But the stylistic range that Picasso embraced in the summer of 1921 hasn’t always found a receptive audience. The catalog of the MoMA show contains an essay entitled “Where Is the Real Picasso?” In the years around 1920 there were critics who worried that he was abandoning the rigors of Cubism in favor of an easygoing eclecticism calculated to appeal to a growing public for modern art. Some of Picasso’s old friends saw a rejection of the avant-garde in his marriage to Olga Khokhlova, a dancer with Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, his move to an elegant apartment on the rue la Boétie on the Right Bank, and his appearances at fashionable soirées. “One remains perplexed by the dexterity and the ingenuity of this artist,” a writer complained in Le Populaire de Paris in 1921. “Here is a man who can do it all, and undo it all, a Proteus. One admires it, but also distrusts it.” What the curators of “Picasso in Fontainebleau” don’t make clear is that in one form or another this critique has only gained traction as time has passed. For some observers, what they regard as Picasso’s embrace of a stylistic pluralism calculated to appeal to a pluralistic public paved the way for Warhol’s vision of modern art as mass market art.

In 1965, just as Pop Art was taking off, the English Marxist John Berger published The Success and Failure of Picasso, a book that was widely read and has continued to have an impact. Berger’s basic argument is that over the years Picasso became more and more interested in using his genius—a genius Berger never denied—as an attention-grabber. The turning point, he argues, was during the period that MoMA has focused on with “Picasso in Fontainebleau.” “For the first time,” Berger writes, “we see the modern artist serving, despite his own intentions, the bourgeois world and therefore sharing a position of doubtful privilege.” Among the works Berger takes aim at is Three Women at the Spring, which he believes “caricatured the classic ideal” and was “like a performance by an impersonator of genius. The performance is too skillful to be considered a mere joke. Yet there is certainly an element of mockery.”

Berger calls this pastiche. What he mistakes for pastiche is the wit in Picasso’s tradition-consciousness. Picasso was right to see an undercurrent of metaphysical comedy in the way that Poussin—in Rebecca at the Well, a painting Picasso has to have been looking at when he was working on Three Women at the Spring—emphasized formal echoes between the shapes of vases and women’s bodies. Berger presents a complex and at times subtle argument, but throughout there’s an insistence on Picasso as a performer on the social stage. “Picasso,” he writes,

is the typical artist of the middle of the twentieth century because his is the success story par excellence…. Art, and especially “experimental” art, has now become a prestige symbol, taking the place, in the mythology of advertising, of limousine cars and ancestral homes. Art is now the proof of success.

I don’t believe that Picasso ever became the artist that Berger has in mind. The artist he’s describing is Warhol, who purveyed “experimental art” (fake experimental art) as a prestige symbol and became the success story par excellence.

There is always a sense in which the conditions of the present color the past, and at a time when contemporary art has become a business bringing in billions of dollars a year, Picasso’s willingness and even sometimes eagerness to put himself before the public can seem Warholesque. The aging artist who in 1958 allowed the photographer David Douglas Duncan to put together a book of pictures, The Private World of Pablo Picasso, in which he puts on funny masks and dances around his studio, might be said to be halfway to the Warhol world. Certainly it’s true that there were times when Picasso’s hunger for a public—a public that had been denied to so many avant-garde artists when he was young—became something closer to a hunger for publicity. But I doubt that anybody, in their eagerness to make Picasso our contemporary, could imagine him announcing, as Warhol did on the occasion of his first show in Paris in 1965, “I thought the French would probably like flowers because of Renoir and so on. Anyway, my last show in New York was flowers and it didn’t seem worthwhile trying to think up something new.” Warhol’s admirers will argue that this is ironic and that I’m being insufficiently lighthearted. I think Warhol was absolutely on the level when he said that his work was all appropriation, all replication.

Warhol became a star by refusing to believe that there was anything private about the artistic imagination. As he put it in the beginning of POP ism: The Warhol ’60s, the book he wrote with Pat Hackett:

I was never embarrassed about asking someone, literally, “What should I paint?” because Pop comes from the outside, and how is asking someone for ideas any different from looking for them in a magazine?

An art that comes from the outside is by its very nature socially driven and socially defined. Fifty years after Picasso’s death a lot of people are inclined to see all art in those terms. That is why Hannah Gadsby could declare, at the opening of “It’s Pablo-Matic,” that the “‘transformative power of [Picasso’s] oeuvre’ has an engine that has nothing to do with the objects themselves. The seed of ‘Picasso power’ lives in his self-manufactured ‘mythology.’”

“It’s Pablo-Matic,” which Gadsby put together with the help of a group of curators at the Brooklyn Museum, was not a favorite with the critics. I think that’s because the show made embarrassingly explicit a thoroughgoing contextualization and politicization of art that many in the museum and gallery world have accepted but would prefer, at least for the time being, to sugarcoat with a little chitchat about beauty. There was no sweet talk in “It’s Pablo-Matic.” The show included some significant Picassos—paintings from the Musée Picasso and some drawings and prints from the Brooklyn Museum’s own distinguished collection—but they were surrounded and challenged by dozens of contemporary works, all of them by women and some more sexually explicit than just about anything the supposedly sex-crazed Picasso ever did.

Then there was a video of Gadsby explaining that high art is “bullshit,” declaring “I hate Picasso,” and mentioning his “ballsack.” People were laughing as they watched Gadsby’s spiel—laughing, I think, with some relief, because they’d been given permission to dismiss whatever imaginative imperatives might have shaped Picasso’s Minotaurs and muses. In a press release Gadsby is quoted declaring,

If Picasso, in all of his misogynistic and narcissistic glory, must be remembered as “the greatest artist of the twentieth century,” let’s also remember that it was that century which carried us into this dumpster fire of a world where absolutely nobody is happy.

Is Gadsby suggesting that Picasso has some responsibility for income inequality and global warming?

In one wall label Gadsby informs museumgoers that there are seven sets of “cocks and balls” hidden in The Sculptor, a painting of the artist in his studio that Picasso made in 1931. A friend of Gadsby’s, we’re told, had a question: “Is it fair to ask me to separate the man from his art when he couldn’t even separate himself from his art in his art?” You can dislike the painting (I don’t think it’s top-tier Picasso), but how does somebody know what they think about the painting when they refuse to distinguish between the artist and the art? A museumgoer who approaches this painting with an open mind and a little patience will see that Picasso is exploring and playing with echoes and parallels between male and female anatomies, the like and unlike taking on a labyrinthine, phantasmagorical quality in a painting in which the artist himself, far from lording over things, is on the point of dissolving into a puzzle of erotic shapes. But to look at The Sculptor in such a way takes us beyond polemic and ideology, which is where Gadsby wants to keep us.

Part of what may fuel Gadsby’s anger (or maybe it’s just cheerful annoyance) is the seriousness of Picasso’s play. There’s a gravitas about his tangled, private mythologies. How can anybody who visited “It’s Pablo-matic” not have responded to the almost baroque solemnity of Minotauromachy (1935), with its daring collage of Greco-Roman and Christological images and ideas? Picasso always aims to engage us, to convince us, and that can feel like an imposition if not an embarrassment to an audience that’s become comfortable with Warhol, whose images are meant to be taken with a “whatever…” informality. There’s a lot of comedy in Picasso, sunk deep in the work, but there’s no irony. That renders him incomprehensible to Gadsby, whose own routines are all irony, all winks, jabs, and insults, delivered with snarling good cheer.

I don’t know what Gadsby thinks of Warhol, but Warhol, too, is all irony—a deadening, depersonalized irony. At “Andy Warhol: Thirty Are Better than One,” an exhibition that filled the Brant Foundation in the East Village over the summer, an entire wall was devoted to a group of his portraits of Chairman Mao, flanked on adjoining walls by his Mona Lisas and Flowers, everything presented in the same take-it-or-leave-it spirit. You might imagine that the liberals who make up most of the audience for contemporary art would cringe at Warhol’s gleeful presentation of Mao, a totalitarian murderer. But no. The glib chic of Warhol’s images lets Mao—and Warhol, and maybe even us—off the hook. Who could be offended by what amounts to a colorized version of a photograph?

There’s no danger of offending in the way that Picasso can offend with his impassioned draftsmanship. That was what happened in 1953, when Picasso made the horrible misstep of producing a gently sympathetic portrait drawing of Stalin shortly after his death that was published in one of the French Communist newspapers. People are still arguing—and arguing passionately—about Picasso’s drawing of a man who slaughtered millions. The impersonality of Warhol’s work puts his Maos beyond the reach of such discussion. Since Warhol has kept Mao at arm’s length—all he’s done is crop and color a photograph, more or less exactly what he’s done with Campbell’s soup, Marilyn, and Goldsmith’s photograph of Prince—nobody can imagine that he’s making any kind of judgment.

Warhol’s output, celebrated by his admirers for holding up a mirror to our consumer society, has left too many sophisticated museumgoers imagining that all artists are essentially social animals, not only in their careers but also when they’re in their studios. Warhol’s insistence that art not only ends but also begins in the public sphere—“Pop comes from the outside”—has altered, perhaps irrevocably, the understanding of earlier art, and certainly of Picasso. Art has been externalized; it’s now a matter of branding, marketing, consumption. And Picasso, in our Me Too era, is regarded as a compromised brand. In her widely discussed book Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma, Claire Dederer brings a playful intellectual swagger to her ambivalent feelings about Picasso’s brand—as well as the reputations of a number of other creative individuals, including Woody Allen, Roman Polanski, Joni Mitchell, and Doris Lessing (the women abandoned their children). I’m put off by the memoiristic coziness of Dederer’s polemic. But nobody can deny that she’s saying what a lot of people are quietly thinking, namely that it’s OK to like the artist’s work even though you dislike the artist.

Dederer’s argument would be even stronger if she didn’t so often insist on seeing the artist as a social product. She writes:

The fact that Picasso embodies our image of the genius is not an accident—or maybe it is an accident of history. Picasso’s rise was contemporaneous with the explosion of mass media. Picasso became the image of art itself…. His image and his persona were perfectly matched to the moment.

Dederer is too acute an observer to imagine that genius is nothing more than a social phenomenon. But there are risks involved in focusing on the consumers of culture rather than culture itself. Genius isn’t a social contract. Genius is an extraordinary quality of mind and imagination. We recognize genius not through a person’s conduct in the world but through the quality of the work that the person produces, whether Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway, Einstein’s theory of relativity, or Picasso’s Ma Jolie.

On the cover of Monsters there’s a photograph of Picasso standing bare-chested on a beach, his head entirely covered with a mask in the shape of a bull’s head. To a reader of Monsters this photograph might represent the essence of Picasso—the macho man, the bully—although Dederer probably wants the informality of the snapshot to add a bit of an ironic wink. What’s actually happening here is that Picasso, by putting on a little act for the photographer, is reminding us how dramatically different the man standing on a beach is from the man in the studio who produced the bull that dominates Guernica and the bull-headed figure in the Minotauromachy.

Some fundamental unwillingness or inability to distinguish between the artist’s career and the artist’s work now shapes much of our intellectual life, and that can be true even where it’s clearly not intended. I don’t imagine that Hugh Eakin, a journalist who’s written incisively about controversies involving the antiquities trade, imagined that he was turning Picasso into a figure out of Warhol’s world when he wrote Picasso’s War: How Modern Art Came to America. But to a certain extent that’s what he’s done.

Eakin set out to tell the story of Picasso’s reputation in the United States, from Alfred Stieglitz’s daring show of Cubist drawings in 1911 through Alfred H. Barr Jr.’s efforts, as founding director of the Museum of Modern Art, to establish the Spaniard as something like the central figure in the modern movement. But despite the title, Picasso’s War has little to do with Picasso. It’s a book about the marketing of modernism. What interests Eakin is reputations, sales, crowds—the Warhol effect, only before Warhol emerged.

Readers who aren’t familiar with Barr—or the great American collector and connoisseur John Quinn, who dominates the early chapters of the book—will be interested in their formidable attempts to find a responsive audience in the United States for art that everybody acknowledged was challenging. As for Picasso, he could be almost diffident when it came to advocating for his work, though some of that was obviously the slyness of a salesman who was a brilliant self-publicist when it served his purposes. More often than not, however, Picasso is offstage in Picasso’s War. When he does appear it’s sometimes to give the cold shoulder to even his most ardent advocates, the most famous case being Barr, who didn’t find him easy to deal with. Picasso was a manipulative man—there’s no question about that. What Eakin can’t explain is why. That’s because so much of Picasso’s manipulation had to do with protecting himself. What really mattered to him were the transformations that were taking place in the privacy of his studio, not out in the world.

To measure the distance between what went on in Picasso’s studios and what went on in the place where Warhol worked—what he called the Factory, with its ever-shifting cast of superstars, worker bees, and hangers- on—you have only to turn to Picasso Plain. Parmelin and her husband, the painter Edouard Pignon, were among a small group of people who were close to Picasso in the postwar years, when he and Jacqueline were living in relative solitude in the South of France, a peace interrupted only by visits to the bullfights that he adored. Parmelin was keeping Jacqueline company while Picasso, sequestered in an upstairs studio for hours and days on end, was immersed in his versions of Las Meninas. “What an appalling business!” he exclaimed when he took a break from his work. His versions, according to Parmelin, “were his furies.” “People think it’s easy,” he told her, “I really don’t know how people can think it’s easy.” For Warhol it was easy, but that’s because he wasn’t changing anything, wasn’t transforming anything. Each Picasso—Still Life on a Piano, Three Women at the Spring, Three Musicians, Minotauromachy, the variations on Women of Algiers and Las Meninas, the list goes on—is a work of art to which Picasso gives a life of its own. As for the Warhols—the Campbell’s soup cans, the Marilyns, the Maos—they’re all the same. They’re just Warhols.

-

*

“The Supreme Court Is Wrong About Andy Warhol,” The New York Times, June 5, 2023. ↩