The Danish novelist Harald Voetmann said in an interview last year that his most recent trilogy was inspired by a nightmare he had in Ascea, Italy. He didn’t describe the dream in the interview (or in any other public forum that I can find), but whatever darkness visited him that night seemingly persisted throughout the writing process. “I was very unhappy when I wrote both Awake and Sublunar,” he said, speaking of the first two books of the trilogy, which have recently been translated into English. “It came to a full stop while I was in the middle of writing Sublunar and turned into a real depression that made it impossible for me to write anything for about six months.”

Origin stories are notoriously suspect, especially those reported by writers, and my curiosity about the dream is probably misplaced. I mention it only because reading Voetmann’s slender, bilious historical novels is not unlike descending into a nightmare. This is in part because of their lurid lyricism—their pages are rife with piss and pus, mud and shit; there are stews stained with gull’s blood, embalmed giants whose desiccated corpses hang from hooks in the Roman gardens, and a peasant who freezes to death in the act of defecation; in one highly detailed scene, a legless man is coerced by a group of carousers to have sex with a prostitute for their amusement, which he does, using as leverage only the partial, deformed foot that grows from his buttock. But it is also because they prompt the irreducible fascination that is characteristic of nightmares, hallucinations, and mystical visions, in which horror approaches the sublimity of beauty and arrives with the force of revealed truth.

The horror in these novels is the cruelty of nature—her indifference to human aims, her perpetual cycle of change and decay—a subject that, like the use of the feminine pronoun, has been relegated to history and is plausible only in the realm of historical fiction. Awake is set in the early Roman Empire, and Sublunar in sixteenth-century Scandinavia, but their protagonists are prototypically modern: men of science who are intent on outrunning this primal nightmare. Both, crucially, are insomniacs.

Awake centers on Pliny the Elder, whose obsessive desire “to name and classify the world’s miseries” in his encyclopedic Natural History keeps him up at all hours. Throughout the novel he lies in bed with a nosebleed, wheezing, his nostrils stuffed with wool soaked in rose oil, dictating passages to Diocles, his slave and secretary. His narration drifts freely from scholarly observations (the distinctions between eagles and vultures, the soul’s role in digestion) to childhood memories of walking with his mother through the Gardens of Sallust, where street vendors hawked clay figurines and ivory miniatures, and where he once witnessed the brutal mating ritual of dragonflies. As the male mounts and appears to murder his mate (females often feign death to avoid unwanted sex), the child Pliny gets his first glimpse of life’s brutality. “I collected it in my hand,” he recalls of the dragonfly corpse. “It filled my palm. I could see a puncture on its neck. I shuddered more profoundly at the sight than I would at any of the later battles of beasts or gladiators my father and his peers let me watch from the equestrian seats.”

Awake is structured like an antique drama: episodes of action (or more often inaction; Pliny mostly remains in bed) alternate with excerpts from the Natural History, letters, and interludes devoted to ancillary characters. Several sections are narrated by Diocles, who suffers from nightmares and, when he is not transcribing, roams around the house seeking distraction, harassing the kitchen maid for sex. “Nothing is more depressing than to be filled with semen to the point of bursting,” he complains. Pliny is more than a little stifled himself, but unlike Diocles, the male dragonfly, and the bloodthirsty spectators of Roman entertainment, he has sublimated the masculine drive for domination into intellectual pursuits.

The best form of revenge against nature’s “sublime cruelty,” he concludes, is knowledge: “We must learn to enjoy the cruel game, and so be it that it is at our own expense. Learn each of the varied malformations she may inflict on us, relish the endless kinds of miseries imparted daily by her creativity.” The novel is acutely aware of the futility of this quest, and takes a certain delight in undermining it. During the day, as Pliny tries to nap, he’s kept awake by crowing cocks, barking dogs, and hissing cicadas—all the creatures his zoology strives to classify. His taxonomies, one senses, are a form of taxidermy, motivated by a desire to silence nature into the clean austerity of a system.

Voetmann likes to reiterate in interviews that Pliny once called nature “humanity’s evil stepmother.” “I was intrigued to find such an aggressive and hateful voice at the root of Western natural philosophy,” he has said. Readers of Pliny may be bewildered by this characterization of his work—or suspect Voetmann of projecting onto it some of his own psychic darkness. The Natural History clearly contains less rage than wonder. Its pages spill over with ornate arcana, exotic mirabilia, and those delightful follies our more dogmatic age insists on calling “misinformation”: the assertion that goats breathe through their ears or that hyenas change from male to female. “It is thought to bring good luck to spit into urine immediately upon discharging it,” reads one Pliny line quoted in Awake.

Advertisement

Voetmann, of course, is well aware that the biases of the present often color and distort the past. Throughout the novel he intersperses these actual excerpts from the Natural History with fictional commentary by Pliny’s nephew, “the Younger,” whose voice is more urbane and detached, and who steps in to correct his uncle’s errors—often with errors of his own. When the Elder insists that stars have appeared on earth, forming “a halo around the javelins of soldiers who guard the camp at night” (a passage believed to be about St. Elmo’s Fire), the Younger snidely remarks that his uncle is “confusing stars with fireflies or something.” When the Elder insists that there is no relationship between human affairs and the stars, the Younger notes some exceptions: “A bright new star was born in the sky upon the death of Caesar, and upon the enthronement of our mighty emperor Trajan a new star was observed, heralding the immortal glory awaiting him.”

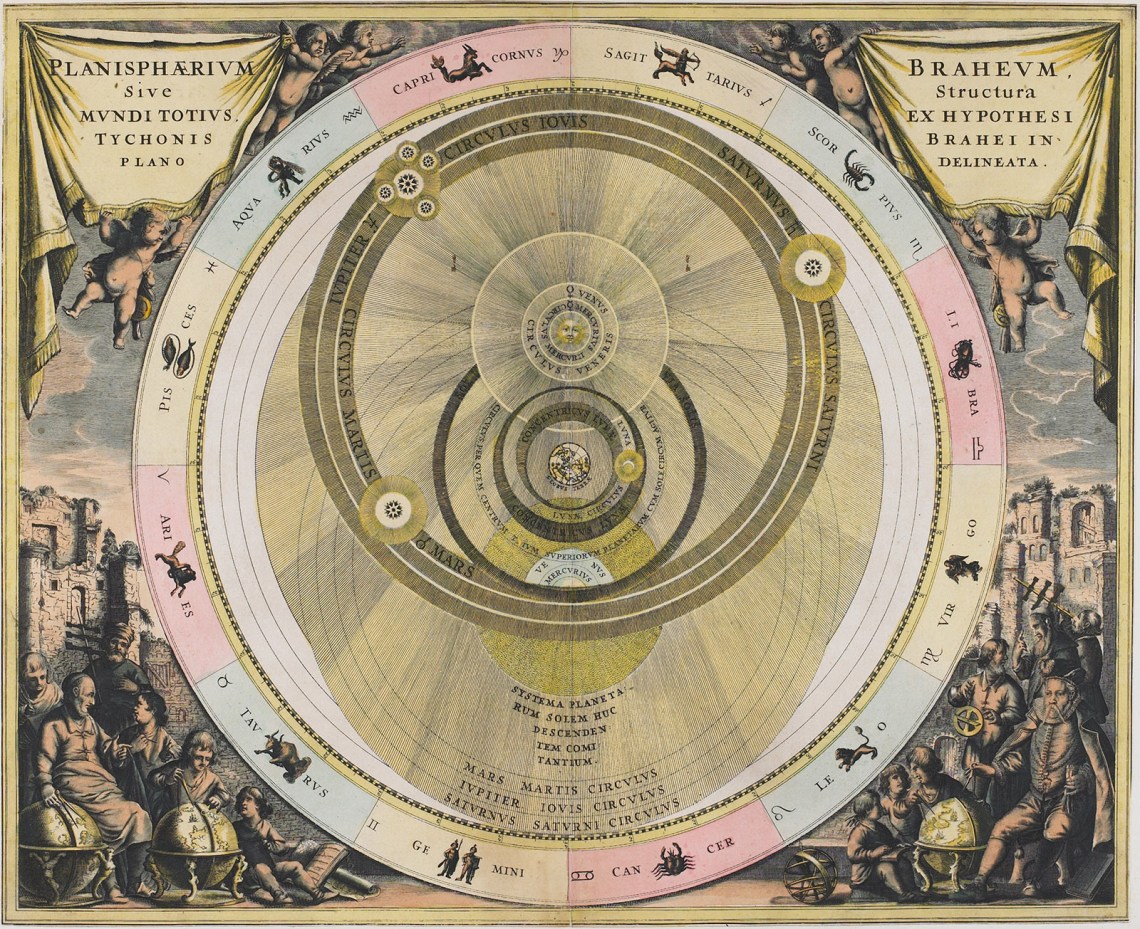

Awake and Sublunar are like neighboring constellations—two clusters of themes and patterns whose borders overlap—and it’s fitting that stars serve as their ligature. Pliny the Elder was among the first to propose that “the stars we think are fixed actually move,” citing Hipparchus’s documentation of a new star in Scorpius in 134 BC. It was not until 1572 that another stella nova was spotted, above Denmark. The astronomer and nobleman Tycho Brahe saw it one November night while walking home from his uncle’s laboratory. He did not believe his eyes, and called over some peasants to confirm that he was not deluded.

The very notion of a new star was heretical to Christian doctrine, which insisted that all change and decay were confined to the sublunary realm—the fallen, sin-stricken earth. The sky belonged to the eighth sphere, the realm of eternity and cosmic perfection. Tycho spent the next fifteen years in the throes of manic sky watching, inventing new and more exact instruments, trying to understand the meaning of this new star. His quest was enabled by King Frederick II, who funded Tycho’s astronomical research on the island of Hven, where he built the whimsical Uraniborg, a sandstone castle equipped with an underground laboratory and a tower from which he and his attendant scholars could observe the sky.

Sublunar, the second novel in Voetmann’s trilogy, follows the life of Tycho and his assistants at Uraniborg as they document the stars and struggle to ignore the ground shifting beneath their feet. The scholars stay up all night conducting stationary observations of the clouded sky, measuring parallax with their compasses and sextants. (The telescope had not yet been invented.) “No other place on Earth has such poor visibility,” Tycho complains. Sweden, “this soup tureen of a country,” as he calls it, is surrounded by fog, mist, and marshy vapors. At night he dreams that the fog has permeated his castle, blurring the boundaries between rooms, erasing his meticulous tables and charts: “Every page of my logbook is blank, every coordinate has been wiped away.”

There is a strain of dramatic irony here for readers who grasp the historical context: it was not fog and poor visibility that obstructed Tycho’s understanding, but his own intellectual prejudices. Although his data clearly proved that Earth revolves around the Sun, he remained unwilling to accept this conclusion; it would be left to Kepler to make that leap. In Voetmann’s telling, Tycho’s dreams suggest that his unconscious has begun to grasp the truth his waking mind resists—that there is no longer a clear boundary between heaven and earth, that the snow globe of medieval cosmology has already fractured into the Pascalian terror of infinite spaces and eternal silence.

The jacket copy of Sublunar refers to Tycho as “the most illustrious noseless man of his time,” a nod to the fact that he lost part of his nose in a duel. When a physician suggests recreating the nose with a graft from his arm, Tycho rebuffs the offer, recalling that Pythagoras had a thigh made of gold. “So why would I want a snout made from worthless arm flesh?” Instead he wears a wax prosthetic. It’s another link between him and Pliny, with his wool-stuffed nostrils. Smell is the most primal animal sense, and its obstruction in both men literalizes science’s fear of physicality.

Advertisement

For Tycho, as for Pliny, the desire to transcend the sublunary world of sense and physicality is fundamentally aggressive and misogynistic, with nature imagined as essentially feminine and science as an instrument of domination. Uraniborg was named after Urania, the muse of astronomy, whom Tycho dreamed of imprisoning in the dungeon of his castle. “To watch the immaculate heaven from below without any malice is difficult,” he admits. The confession is addressed to his unborn twin, whom Tycho calls “brother of my heart” and “native of Heaven” in a series of letters scattered throughout the novel. (The real Tycho once published an ode narrated from the perspective of this brother, who had died in infancy.) So intense is Tycho’s longing to transcend this realm, he believes that his twin enjoys the preferable fate, having been shuttled directly from the womb to the amniotic warmth of eternity.

Like Awake, Sublunar borrows a form—the Renaissance almanac—native to the era it dramatizes, and is a bricolage of poems, letters, and excerpts from an unfinished alchemical treatise. Roughly half the book is structured as a weather log (one that is loosely based on Tycho Brahe’s real meteorological journals, kept by various assistants on Hven from 1582 to 1597) written by a melancholy scholar who dutifully notes changes in precipitation, cloud cover, wind direction, and the position of the stars—a task that irresistibly tilts into lyricism:

Dark the whole day and night, fairly southwest. Sea, sky, and island are leaden, even in the light there is something saturnine, a dullness maybe, or a heaviness. All colors appear to be a thin smear of luster, a fire film covering the gray which is the true matter, as though the brush of a finger might wipe the colors away.

We learn very little about this anonymous assistant—his origins, his biography—apart from what he observes of daily life on Hven. Throughout the long Nordic winters, the assistants sleep beneath wolfskin, eat liver loaves and bird pâtés with their fingers, and occasionally look up to see a peasant staring at them through windows hoary with frost. Visitors are always arriving and departing, princes and dukes, bands of musicians from Elsinore and Copenhagen. Evenings are given over to lavish banquets during which the young guests vomit in the herb garden and are entertained late into the night by Jeppe, Tycho’s dwarf. The plague has already descended upon Europe, and one of the scholars learns from a letter that his mother’s groin has broken out in boils. The assistant tries to distract him by taking him to see a prostitute in town, but she refuses “to whore on Easter Sunday.”

Although he is tasked with watching the stars, the assistant’s eye is hopelessly drawn to the fallen earth. He writes of peasants beating to death a porpoise that had washed ashore and an old dog that had already begun to die. “Her hunting days are behind her and she showed little interest in her surroundings; pain has driven her deep into herself.” Unlike Tycho, with his cyborg nose, the young scholar cannot stop the world from infiltrating his body: his log is full of the pungent whiff of pigsties and hay, of alchemical gold that reeks of vinegar and mold, of the salty stench of mist and mud pools. “Brine and loamy earth pervade our every breath,” he writes. Much like Pliny’s slave Diocles, the assistant serves as a tragic counterpoint to his master’s longing for Platonic perfection, bringing the novel’s gaze back to nature’s perpetual cycles and the impossibility of transcendence. “Each day the dead pile up under our feet but we are brought no closer to the stars,” he observes.

History may not have favored his pessimism—Tycho is now celebrated as one of the fathers of modern astronomy—but Sublunar gestures toward those darker truths that are often obscured in celebratory accounts of the Enlightenment. The star Tycho spotted was not in fact the birth of something new, but the death of something very old: novae stellae, today known as supernovas, are dwarf stars at the end of their life cycle, their brilliance the product of their impending death. That this dying star initiated the birth of modern astronomy appears, from our vantage, largely accidental, and Tycho in any case did not live to see his discoveries bear fruit. An undercurrent of futility similarly runs through Awake, whose final chapter dramatizes the tragic fate of Pliny: the man who insisted on conquering nature was killed by the eruption of Vesuvius. The human drama, the novels suggest, lacks the novelistic arc we moderns have imposed on it and is instead one perpetual cycle of hybris and nemesis, a tragicomedy in which Mother Nature always has the last laugh.

I read Voetmann’s trilogy during an interminable summer of heat, drought, and wildfire smoke, a season in which the novels’ garish imagery permeated my dreams. I woke each morning to vague memories of horror—disembodied limbs, animal skulls, bloodstains—and a phrase from Beyond Good and Evil looping through my mind: “We, whose duty is wakefulness itself…” The alertness that Nietzsche prescribes is not the “awakening” often associated with scientific knowledge but, on the contrary, an attentiveness to truth as fluid and chimerical. It’s time, he announces, for humanity to finally abandon the “nightmare” of dogmatism that runs through Christianity, Hegelianism, and empirical science, which has tried in vain to reduce life to a system of inflexible rules. It’s the same passage in which he remarks that truth is a woman—fickle, variable—and that the futility of human thought stems from the fact that most philosophers don’t understand women.

Voetmann’s trilogy contains more than a trace of this Nietzschean critique, dramatizing the follies of masculine genius as it tries in vain to subdue the elusive and indifferent goddesses—Nature, Fortune, Truth. The men who dominate the novels similarly fail to understand women or to see them as anything more than vehicles for their often violent sexual desires. The female characters in the two books are largely limited to prostitutes, peasant women, and distant mothers. (Sophia Brahe, Tycho’s sister, makes a brief appearance in Sublunar, but the novel declines to elaborate on her contributions to his scientific achievements.) Presumably the cruelty inflicted on women is thematically purposeful, mirroring the way science is driven by the toxic male desire to conquer nature.

But ultimately, the trilogy is not satirizing science so much as systems themselves (the third novel, Visions and Temptations, not yet published in English, is about medieval Christianity) and the dominating impulse that, much like the male dragonfly, tends to murder what it loves. The human desire for knowledge begins with mystery and awe—the bestiary, the lapidary, the saint’s mystic vision—and calcifies into dogma: scientific logs, religious doctrines. “I think if you look at the three books together,” Voetmann said in 2022, “they might…be about the different systems of thought we construct: philosophical, religious, scientific, and our lives within these systems. We tend to build them and they always tend to crush the humanity out of us.”

Yet the novels suggest other ways of knowing. While systems operate from the top down, imposing rules on chaotic reality, there are also those convictions that arise from the ground up: the sudden insights that arrive in nightmares and visions, the associative patterns of augury and alchemy. It’s telling that the only character in Sublunar who understands the implications of the new star is Falk Gøye, an alchemist. “The spheres of heaven can no longer be called unchanging and eternal,” Gøye writes in his commentary on the apocalypse, a fictional alchemical treatise that constitutes the middle portions of the novel. The cellar of Uraniborg was in fact given over to mystical rituals (Tycho, like Galileo, dabbled in alchemy), including attempts to transmute gold in its sixteen furnaces, known as “the sixteen gates of hell.”

Voetmann is alert to the symbolism embodied in the castle’s design: the star-watching tower is a monument of Apollonian rationalism, while the laboratory’s basement functions as a synecdoche for the human unconscious. As the scholars meticulously chart the heavens in their logbooks, Gøye kneels before cellar furnaces, chanting Latin verses about rising phoenixes and mythological kings, “grunting the famous words of Paracelsus, that everything of benefit to mankind will be reborn in flames.” Unlike the dream of eternal perfection—the stars fixed in their eternal place—alchemy allows for the necessity of transmutation, and is perhaps more reflective of nature’s restlessness, which is always changing one thing into another and is difficult to predict or control.

Given the slender line that once separated astronomy from astrology and chemistry from alchemy, it’s arguable that these two epistemologies are not inimical but complementary. The American philosopher Edwin Arthur Burtt claimed that the most remarkable and exasperating feature of the scientific revolution was that “none of its great representatives appears to have known with satisfying clarity just what he was doing or how he was doing it.” Just as Columbus discovered the New World while searching for India, so the exact laws of modern physics emerged from the brume of Pythagorean mysticism that preoccupied men like Tycho, Newton, and Kepler (the last of whom stumbled upon universal gravity while trying to prove that the universe was a harmonious whole comprised of crystal shapes or perfect chords made in the image of God).

It’s a conclusion that similarly guides Arthur Koestler’s history of astronomy, The Sleepwalkers (1959). The haphazard, accidental way that most fundamental discoveries were arrived at, Koestler argues, “reminds one more of a sleepwalker’s performance than an electronic brain’s.” It’s an insight that feels enduringly relevant—or it did to me, at least, throughout that summer of smoke and dread, when particulate matter obscured the sun and the headlines were full of warnings about AI systems whose opacity and unpredictability had garnered comparisons to alchemy.

Can we ever escape the Joycean nightmare of history? Or has our awakening amounted to a series of lucid dreams that accident and luck have led us to trust? Voetmann has noted that Ascea, the city where he had the nightmare that inspired the trilogy, is not far from Elea, home to the pre-Socratic philosopher Parmenides, and Awake begins with a quote from his work On Nature: “It is the same to me where I begin for I shall go back there again.” In the march of progress, perhaps the divergent paths of measurement and mysticism lead, in the end, to the same destination, which starts the journey all over again. Stars blaze and burn out; theories are born, die, and rise again. The eternal truth, what Parmenides called “Being,” appears in flashes and eludes our attempts to outsmart its destructive potential. As Voetmann puts it, more succinctly, “We are still deep in the shit and our science has not saved us.”

Voetmann, too, seems to work from the ground up. Although Awake and Sublunar might be called novels of ideas, Voetmann’s intellectual concerns are not forcefully imposed upon fictional dramas arbitrarily designed to illustrate them, but rather arise from particulars that are irreducible. Each page of the books contains a richness of detail and a depth of attention that has all but vanished from the contemporary novel—or, for that matter, any other mass-produced object. His narrators frequently pause to admire a fine piece of craftsmanship: a golden ring with an engraving of a slithering snake; ivory miniatures in walnut shells, for sale in the Roman market, on which you can have your entire ancestral history carved in Greek or Latin; a codpiece adorned, on the front, with a depiction of Jonah in the whale, and a bathing Susanna painted on the underside.

The novels themselves—each scarcely more than a hundred pages—are miniatures that appear to have been less written than chiseled. Images glow in stark relief against the somber backdrops and recur with slight variations, as though guided by a Fibonacci sequence. Amid the guts and gore, there are moments of quiet splendor. In Sublunar, the assistant pauses one morning to describe a group of young Courlandians (that is, Latvians) bathing off the shores of Hven:

Their long cloaks and gowns floated around them on the surface so that at a distance both men and women looked like colorful waterlilies that together formed a changing and interlocking pattern—at one point close to a spiraling chain of pale nobles framed by bright petals, the Duke himself at the center, inside a circle of undulating golden cloth. Next year some of them will be dead, as will some of us, and even if this pattern, or parts of it, could be re-created exactly, there may not be anyone alive who has seen it, from this height and distance. Only God in Heaven, for whom the Courlandish spiral may be a significant symbol, could readily appreciate it.

After a century or so of proclamations of its death, it’s difficult to recall that the novel is, as its name announces, a stella nova, a form that is by its very nature devoted to novelty, the new, the modern. Walter Benjamin argued, in a 1936 essay, that the form had replaced the patient craftsmanship of the storyteller, who passed traditional tales down from one generation to the next, and who lived more comfortably with the idea of eternity. He quotes Paul Valéry speaking fondly of these storytellers of yore, who were inspired by the slow-cooked works of nature, “flawless pearls, full-bodied mature wines, truly developed creatures,” all of which were “the precious product of a long chain of causes similar to one another.” It’s this older, slower kind of workmanship that makes Voetmann’s novels feel decidedly unmodern, and which Valéry attributes to the storyteller’s alignment with nature:

This patient process of Nature was once imitated by men. Miniatures, ivory carvings, elaborated to the point of greatest perfection, stones that are perfect in polish and engraving, lacquer work or paintings in which a series of thin, transparent layers are placed one on top of the other—all these products of sustained, sacrificing effort are vanishing, and the time is past in which time did not matter. Modern man no longer works at what cannot be abbreviated.

This more generous understanding of nature—as an artist and a creative source—is largely absent in Voetmann’s portrayal of Pliny and Tycho, who cannot see beyond the world’s cruelty and their own desire for conquest. Their historical counterparts were not so single-minded, and the one blight on Voetmann’s novels stems from his failure to grant his characters the complexity of vision that is evident in their own work. The notion that nature was a patient artist, guided by the principles of cosmic balance, appears throughout the Natural History, which was not only an encyclopedia but the first work of art history in the Western tradition. Pliny’s discussion of marble, crystals, agate, and fossils inspired countless Renaissance goldsmiths and engravers who sought to emulate this geological craftsmanship. The naturalist’s famous line about nature being mankind’s evil stepmother is given not as a proclamation but as an open question: “Her very many gifts,” he writes, “are bestowed at a cruel price, so that we cannot confidently say whether she is a good parent to mankind or a harsh stepmother.”

Gifts that come at a cruel price: artists and alchemists have always understood this better than men of science, whose fundamental error is the belief that you can get something for nothing, that progress, transcendence, and beauty do not exact devastating costs. The rotting fruit produces the full-bodied wine. The painful grain of sand engenders a perfect pearl. The suffering of the artist is transmuted in the furnace of the creative process. Voetmann noted in an interview that midway through writing Sublunar his depression worsened and then eventually subsided. He didn’t disclose how he escaped the dark night of the soul, but his novels are evidence of the fundamental mystery of this process, which occasionally forges gems out of that which it does not destroy. “I was lucky,” he said. “I found a way out.”