In the first volume of his memoirs, Forbidden Territory (1985), the Spanish novelist Juan Goytisolo describes a moment in Paris in the late 1950s when he and some friends were watching news and documentary films about the Spanish Civil War, including footage of the aftermath of the aerial bombing of Barcelona by fascist forces on March 17, 1938. “In the foreground,” he writes, “the camera slowly pans the victims’ faces and, soaked in cold sweat, you suddenly realize the harsh possibility that the face you fear may suddenly appear.” Goytisolo’s mother, Julia Gay, had gone to visit her parents in the city on the morning of the bombing and had been killed. In Paris two decades later, he rushed from his seat, drank “a glass of something,” and managed to “hide [his] emotion from the rest and discuss the film with them as if nothing had happened.”

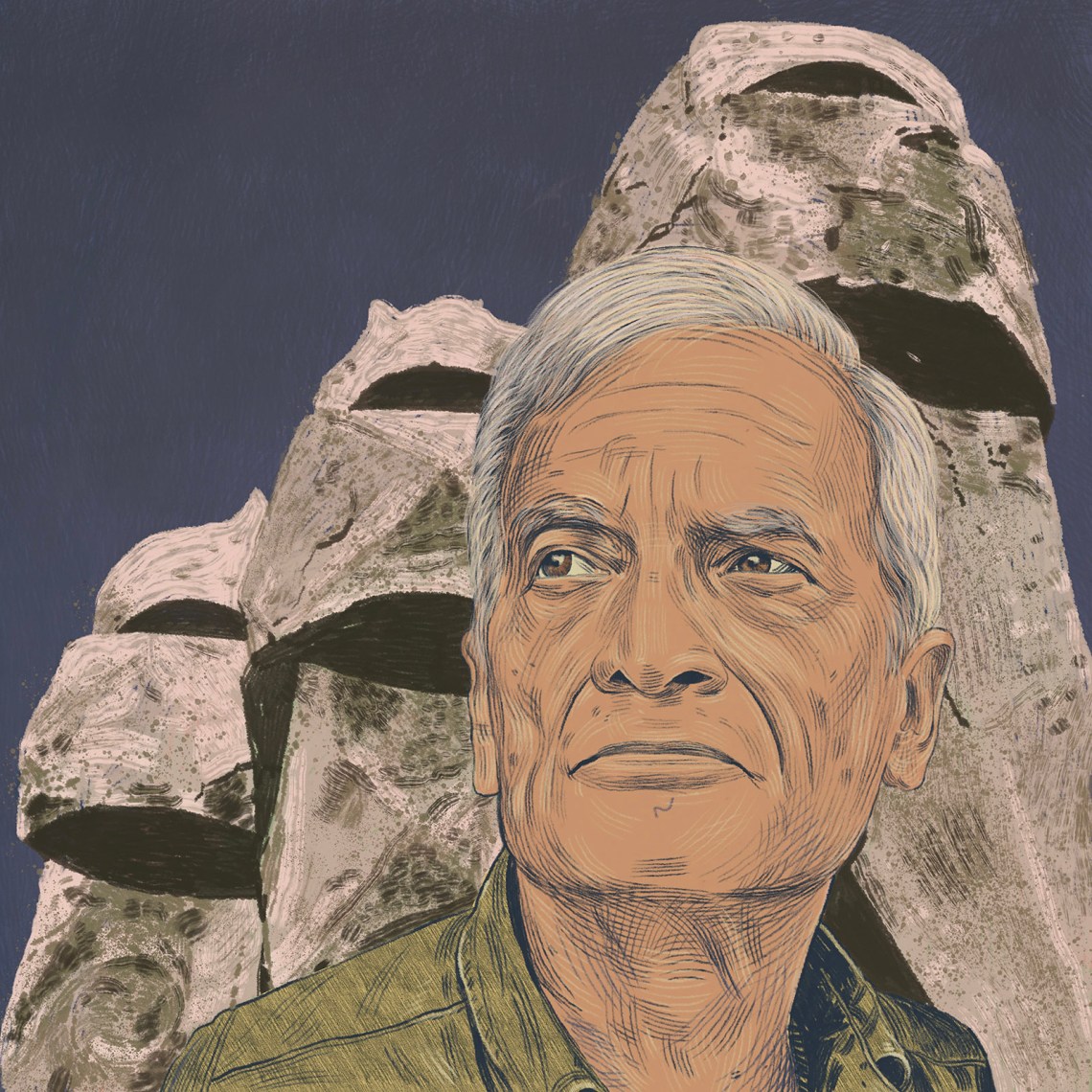

Three of Julia Gay’s children became writers: José Agustín, born in 1928, was one of the most admired poets of his generation; both Juan, born in 1931, and Luis, born in 1935, grew up to be important Spanish novelists. (Juan won the Premio Cervantes, the most prestigious prize in the Spanish-speaking world, in 2014. Luis became a member of the Royal Spanish Academy in 1995.)

Although in Forbidden Territory Juan wonders about “the tricks that memory and its fictitious recreations play,” he is nonetheless sure that he actually saw his mother depart on the day that she was killed: “It is a real image and for some time it filled me with bitter remorse: I should have shouted to her, insisted that she give up the visit.” José Agustín dedicated his first book of poems, El Retorno (1955), “A la que fue Julia Gay” (to she who was Julia Gay). He later published a collection called Elegies for Julia Gay. Like Juan, he imagined how it might have been otherwise. In an early poem, he wrote about his mother’s grave “right here/where you wouldn’t be/if that beautiful morning with the music of flowers/the gods hadn’t forgotten you.”

Reading works by the three brothers is close in ways to reading James Joyce’s Ulysses along with the two books by his younger brother, Stanislaus Joyce—My Brother’s Keeper and The Dublin Diary—and seeing the artfulness beside the raw material. The difference is that none of the Goytisolo brothers wrote in the others’ shadow. Each of them set out to create works of pure individuality and high ambition.

It is nonetheless fascinating to place Forbidden Territory, which includes an account of Juan’s Barcelona childhood, beside the first volume of Luis’s novel Antagony, which covers some of the same events. This allows us to understand more clearly the strategies Luis used to elevate, transform, and transcend his background. Antagony is made up of four books: Recounting, published in Mexico in 1973 and in Spain two years later; The Greens of May Down to the Sea (1976); The Wrath of Achilles (1979); and Theory of Knowledge (1981). “Its broad outlines,” Luis explained, “crystalized in a matter of a few hours one day in May of 1960” while, as a young militant Communist in Franco’s Spain, he was being held in solitary confinement in Carabanchel Prison in Madrid.

Toward the end of Recounting, however, his protagonist, Raúl Ferrer Gaminde, does not see his notes written “on squares of toilet paper” in prison as crucial elements of his growth as a writer. Instead they

came to seem to him like those notes one takes upon waking up in the middle of the night, because the ideas seem to be extraordinarily important, but which in the morning, if they seem to make any sense at all, never usually mean what they did before.

This refusal to locate easy significance gives Goytisolo’s narrative a kind of energy. He writes that there are

moments in a man’s life which, for their metaphorical strength, come to be a summary or compendium of all his conscious and unconscious perceptions, the concentration, one within another, of all implicit experience…a time vastly superior, in its elasticity and amplitude, to chronological time.

But this is just a passing thought; it does not mean that his novel has to take such moments too seriously or deal with them much.

Instead Goytisolo is concerned with surfaces. He uses prose rhythm rather than events or plots as his engine; he likes long, snaking, metaphor-laden sentences; he favors accumulation and addition rather than culmination or concentration. He offers total immersion, creating a tone that is flexible enough to take him anywhere, away from Raúl’s life or his family or his arguments about politics into lengthy considerations of the Catalan character or a disquisition on the niceties of Catholic ritual or vivid and detailed descriptions of Barcelona. These are not asides or breaks in the main story. The novel’s shape is provisional enough to integrate them fully.

Advertisement

Antagony is almost garrulous; many of its paragraphs are probably too long. Sometimes there is a flatness or too much striving for effect. And yet the narrative, in Brendan Riley’s translation, has a way of carrying the reader forward. At its best, the novel soars, using virtuoso imagery and bravura textures.

Raúl in Recounting has no real interior life. We do not see him in deep reverie and solitude, as we do, say, Stephen Dedalus in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Rather, Raúl is what he does. And much of the time he drifts. In the 1960s in Barcelona, many offered support to the Communist Party because it was one of the very few ways of actively opposing the Franco regime. It is not as though Raúl, from an upper-middle-class family, has a sudden political awakening or an acute awareness of the dialectic. His involvement in politics is both passionate and amateur. His arguments with his friends about communism lack depth; it is an aspect of Goytisolo’s genius that he can still make these long discussions interesting. Sometimes this is achieved by parody, deliberate banality, or comic monotony, as when a comrade of Raúl’s expounds on the subject of the working class, calling Raúl by his nom de guerre, Daniel:

The working class is not one worker, Daniel, but rather the proletariat considered as a whole, a whole that is different from the sum of its parts, and therefore not simply theoretical data, but, similarly, eminently operative in the terrain of praxis.

Although Raúl and his comrades get arrested, their families are often able to have them quickly released. Raúl’s friend Federico, for example, notes how the police, having detained him,

suddenly changed their behavior…It must have been when my parents started using their influence. It seems that they showed up at the Headquarters and, since they wouldn’t let them see me, they got the governor to intervene or I don’t know what. Like a gentleman, I’ve come out like a gentleman.

If Raúl is a submerged, unwilling hero, the novel’s real center of energy is Barcelona itself. As he considers the city’s topography, Goytisolo writes of

streets and plazas that, unlike the streets and squares of Dickens’s London or Balzac’s Paris or even, at a stretch, the Madrid of Pérez Galdós, had not found and perhaps would never find a faithful chronicler for their grandeur and misery.

Part of the reason for this is outlined some pages earlier, when Goytisolo describes the rebirth of Catalan as a literary language “after almost four centuries of silence.” Many date the rebirth to 1832, when the poet Aribau published his “Oda a la Pàtria.” Goytisolo notes that the subsequent flowering in Catalan literature was mainly in the form of poetry. And he goes on to record “another new fact: the appearance of writers born in Catalonia who write in Spanish,” who have the advantage of coming from “a city, Barcelona, particularly open, restless, and reformist, among all the cities of Spain, and into a social class, the middle class, objectively more progressive than the sclerotic Castilian feudalism.”

Goytisolo and his two brothers were part of that group. They came from Barcelona but wrote in Spanish. They were insiders in the great teeming city and outsiders in its language, Catalan. In Antagony, it is possible to feel the strain as a sort of impulse toward making the language—the one he has chosen to inherit—seem molded and lifted high, nothing taken for granted.

In The Greens of May Down to the Sea, Goytisolo offers the early death of his mother as another reason why he, or his narrator, might have favored Spanish over Catalan, or how his soul might fret in the shadow of his mother’s language:

I’m referring here to my curious rejection…of my mother’s family’s language, Catalan…the inhibition which kept me from using it…despite, logically, my understanding it perfectly; the clumsiness which seemed to hinder my expressive fluidity on such occasions however much of an effort I made.

Descriptions of Barcelona emerge in Recounting like a refrain. Goytisolo names the streets in which Raúl and his friends congregate and then charts and lists “the working class townships and districts, Barceloneta, Pueblo Nuevo, San Adrián, San Martín, La Segrera, Santa Coloma, El Clot, San Andrés, Horta, Collblanch, Sants, Hostafranchs, Hospitalet, El Port, Casa Antúnez,” as though he were making a map or creating a panorama or composing a cantata as much as writing a novel.

Advertisement

Hardly any street in the old city is unlisted, undescribed. The narrative returns a number of times to the cathedral,

the lofty naves, like leafy palms or cedars, lightly visible above, vaults deepened by the tenebrous transparency of the stained-glass windows, enhanced by their Gothic ribs, ribs which, as they meet in tight knots, at the bottom of the column, turn shadowy and join together.

Antoni Gaudí’s unfinished Sagrada Família looms large, with its

growing avalanche of lobed, dripping, frond-like forms, like secretions and adherences of flower or bivalve, like ice floes and flower petals, stars configuring the zodiacal plane of the sky in that dark night of Bethlehem, of messianic destiny, Gaudian delight, a pleasure that so soon disappears and once gone gives pain, for no rose grows without thorns.

Goytisolo relishes also the seedy city; he lovingly lists the names of the streets in the recreated nineteenth-century Barcelona, and he notes the ugliness of the new buildings erected in the 1950s. He registers small details, like the bookshops on Calle de la Paja, the pastry shops on Calle Petrixol, the Christmas market near the cathedral, and even l’ou com balla, the egg that seems to dance on top of the waters of a small fountain in the cloister of the cathedral on the feast of Corpus Christi.

In Joyce’s Dublin, the city is generally peopled; the streets matter because of who walks in them. In Antagony, the streets matter in themselves; they have the force of character. Raúl and his friends spend time in them, but then the streets break loose from their setting, streets that have been listed get listed again, and buildings such as the Liceo opera house and the city museum that houses the underground remains of the old Roman city and the bars in the Plaza Real and other bars off the Ramblas all get described as though Goytisolo is not merely compensating for the paucity of nineteenth-century novels set in the city but attempting to imagine a new sort of novel in which urban topography can face its destiny as a character or as a family once did.

Luis Goytisolo was lucky that his brother Juan went into exile in Paris in 1956, around the time this novel begins, leaving Barcelona for him to describe. In Recounting, Luis must have enjoyed giving his protagonist a single brother, Felipe, who is not a writer but a priest. (When his brother gives him his watch, “the band on Felipe’s watch smelled of priest.”) While Juan was also committed to ending the dictatorship, he writes best about it from the perspective of exile, beginning the second volume of his memoir, Realms of Strife (1986), for example, with an account of a plan in 1956 by opponents of Franco in France to assassinate the dictator at a bullfight: “A foreign-looking crack marksman could sit in a nearby box without alarming anyone, shoot and then melt into the crowd.”

It is perhaps too easy but also too tempting to study what was erased by one of the brothers or described in detail by another. In Carme Riera’s introduction to a collection of José Agustín’s journalism, she looks at the question of fact and invention among the Goytisolos. In her conversations with the poet, she writes, he told her how he and his younger brother Juan created their own newspaper as children. And then she notes that there is no account of this in Juan’s memoir Forbidden Territory, “but that does not mean that it did not exist,” she adds, since “human memory is, as we know, fickle and false.”

Julia Gay was killed on Luis’s third birthday. While his older two brothers write about her death openly, she is almost missing in Luis’s novel Recounting. The family of Raúl Ferrer Gaminde—including his father—is dealt with in rich detail, and we slowly realize but are never emphatically told that there is no mother. For much of the book, she is simply not there. She is not a palpable absence, a woman much missed or a ghost; rather she is a name that can hardly be said.

Raúl’s father laments her loss, stating that losing his wife “marked the start of my misfortunes, it was the true tragedy of my life.” But it is not explained how she died. Later, when Goytisolo outlines the way in which old people get used to death, he writes

just like the child whose mother dies when he is too young to even understand the meaning of the word death, and will only understand that she has left him, without managing, however, to comprehend the brutal motivation for such behavior.

Thus it comes as a shock when, on page 515, Raúl is contemplating the old family house and uses the word “Mama”:

And his grandparents’ room, and Felipe’s room, the dampest ones, smelled like emptiness. And the attic, filled with dusty piles of disassembled furniture from the conjugal bedroom Papa once shared with Mama, smelled like old clothes and stale silk.

Within a few pages, Raúl will be married and have a son and will evoke the landscape of the Costa Brava, north of Barcelona. In the last few sentences of the book, questioned by his wife, he says:

I had spent a summer around the other side of the cape, in Port de la Selva. Before the war. I don’t remember anything, of course. But there’s a photo of me there. I must have been just a little more than a year old.

A pebble beach, with boats. And I’m on a boat, and she’s holding me…. It might be the last photo of her. She’s looking at the camera, smiling more with her eyes than her lips.

The war is the Spanish Civil War. The “she” is the mother, a version of the dead Julia Gay. It is only in these last sentences of the book that Raúl invokes her directly.

In The Greens of May Down to the Sea, there is no central character. Goytisolo has resorted to his own imagination, following wherever it will take him, and loosened his tone accordingly. His first subject, the Costa Brava that reaches toward the French border, may be a sort of rocky unconscious. It is generally invoked as a lost place, destroyed by tourists and development, a coast that was once a paradise of coves and hidden beaches and beautiful old fishing towns that now are sad memories. “Which hill to climb to contemplate the town if this hill now forms part of the town?” he asks, noting “building sites, construction projects where there once stood a cork oak forest…perfectly aware that neither the town nor the surrounding area could ever be the same,” and wondering if he had come to this “Florida on the Mediterranean” for the “deliberate purpose of finding an objective correspondence to our own transformation.” His tone moves from the regretful to the lyrical to the crudely hortatory:

My personal advice is that you hasten to buy your own parcel [of land on the coast], any of them, because they are all sure to enjoy the same advantages, every single one of them will offer you the opportunity to arrive at your future residence by the mode of transportation you deem most preferable…. Your lifelong dream, yes, now within reach, keys in hand, through an affordable down payment and easy mortgage installments.

There are novelists who would cut this passage, but Goytisolo is concerned in this volume with giving his narrative a kind of plenitude, using any material that comes to hand, including the tone of a travel writer or an indignant citizen of Barcelona dismayed at what has been done to a precious piece of coast.

His characters are a disparate bunch, interested in drinking and sex and sailing. Names come and go. The Raúl of the first volume is named only once, but he gets a speaking part. Others are part of the broken landscape. One of them, called Xavier, distinguishes himself by taking a large amount of time to vomit in the bathroom of a nightclub. This is described, indeed enacted, in a sentence that is close to five hundred words long. It begins graphically enough—“Xavier letting fly with the nether violence of his gathered intestinal forces”—but then it begins to rise up, comparing poor Xavier’s vomiting to the discharges of a whale:

a barbarous diarrheal evacuation…eruptions which little by little must settle from one extreme to the other, from the vaginal vertigo of the throat to the vulval reliefs of the very last rectal rings.

This does not help with the plot, as there really is no plot; nor does it add texture to the character of Xavier, as Goytisolo here is not interested in character. Instead he wishes to free himself of constraints and see what might happen. He wants to set images loose and find sentences to match them. He seeks to project the self-delighting imagination at work, darting from one subject to another, indulging himself, writing superbly and then overwriting, keeping the voltage high at the expense of subtlety or narrative discipline.

In Recounting, Raúl’s early sexual encounters with Nuria, his girlfriend, are written with exemplary candor and clarity. The sex scenes in The Greens of May Down to the Sea, on the other hand, are more graphic, much cruder, often puerile. It is a novel that moves freely between the aleatory and the deliberate, and some sex scenes are offered as something approaching parody.

There is a brilliant description in Recounting of Raúl and his friends doing their hated military service. The dialogue is perfect; the sense of time and energy being wasted and the clash between Catalan exceptionalism and Spanish authoritarianism are captured with accuracy and verve. There is also a lack of solemnity and heavy-handedness, despite the serious political implications.

Recounting was seized by the Spanish Court of Public Order in 1973 and not distributed in Spain until 1975. Since The Greens of May Down to the Sea appeared in 1976—Franco died in November 1975—its author might have felt more free to deal with pressing public matters. But it is as though the promise of freedom included the freedom not to have to bother too much with politics. Instead of going on marches or joining political parties, the people in The Greens of May Down to the Sea go cavorting on the coast. The author cavorts, too. There is a current of self-assertion in his book, a sense of pure individual will in its style, that might represent the spirit of Catalonia in 1976 more than a novel dealing with the niceties of the transition to democracy.

The Wrath of Achilles, the third novel, is narrated by Raúl’s cousin Matilde Moret, a lesbian writer based in Cadaqués, the most fashionable resort on the Costa Brava. She writes in a style that Goytisolo has made deliberately irritating—all attitude, snobbery, and secondhand opinion. Because the tone is so cliché-ridden, it presents a particular problem for the translator. “Maybe I’m being too blunt about it but the truth is that I find women’s verbal diarrhea exasperating,” Matilde says. And later she finds herself bemoaning both “the everlasting braying of the lower classes” and how “impossible the town [Cadaqués] is becoming, vulgar, overrun by snobbish bad taste, with a reputation for debauchery that only attracts riffraff.”

Even when she enjoys life, there is a great banality apparent in her style: “I ate lunch in the sun, on the terrace, dark glasses shading my eyes from the sparkling sea, blown smooth by the Tramontana. And like the Tramontana, so too my mind, lucid, diaphanous, crystalline.” In his translation Brendan Riley manages to capture something of both the deliberate dullness and the mild preposterousness of the original.

Matilde also includes a section of a novel she wrote under a pseudonym in 1963 and had printed privately. It is an account of the antics of a group of people—mainly Catalans—in Paris in the early 1960s. It goes on for some eighty pages and has many characters, or many names for characters, but it is often hard to tell them apart. Slowly it becomes apparent that all of the problems in this novel of hers are deliberate: it is a sort of parody of a bad novel about young people in Paris. As the story, such as it is, begins to center on a young man called Luis who has been arrested in Barcelona for being a Communist, we realize how close this is to the story of Raúl in Recounting.

And then Raúl himself appears; he has now become “a famous writer.” Having read Matilde’s book, he writes her a letter insinuating that her novel is a roman à clef. She denies that Raúl has anything to do with the fictional Luis, even though they both have been arrested in Barcelona, one in the first novel, written by Goytisolo, and the other in the novel-within-the-novel, written by Matilde. But they are, she adds, “creatures, that’s right, drawn with lines inspired by reality, taken from real people, from myself in the first place. As in all novels, I suppose.”

Thus the novelist Luis Goytisolo writes a novel, using aspects of his own experience that he gives to his character Raúl. These experiences are also used by Raúl’s cousin Matilde—a fictional character who writes a novel under a pseudonym—in the creation of her character Luis. The outlines of Luis’s life in Matilde’s book are recognized by Raúl as his own. Raúl, by this time, has become, like the original Luis Goytisolo, a famous writer.

Matilde, meanwhile, has managed to become more serious, more thoughtful. In a sort of argument with Raúl about the nature of fiction and what reading and writing mean, she takes on a new eloquence: “Not the text but the reading of the text. Not the content of the message itself but rather the impact it makes. Not the bullet but the gunshot wound.”

The fourth novel in the tetralogy, Theory of Knowledge, begins with a narrator called Carlos, a young man in Barcelona who keeps a diary and muses tediously on his own sexual desires and on sexuality in general, including what he calls “the monosexual” (he means “the homosexual”):

Arguing about whether it’s a congenital defect or an induced deformation strikes me as simple-minded nonsense that only serves to accentuate the phenomenon, to provide the monosexual with new alibis.

He has equally fatuous views on Nietzsche:

Marx doesn’t interest me. For what it’s worth, I prefer Nietzsche, who’s not in fashion however much people say he is, nor do I think he ever can be, although, honestly, the influence that he has over certain morons, to the point of making them believe themselves supermen, remains worrisome.

And we also hear about his dislike of cabbage and the reasons why.

Goytisolo is enjoying himself here, creating his narrator as he created Matilde, asking the reader to accept a version of bad writing that, in its own long-windedness, enacts the very process it seeks to undermine. The problem, as in The Wrath of Achilles, is the sheer length of it all, the feeling that Goytisolo the puppet master may have stolen the vices of some of his puppets.

Carlos’s diaries are found and read by a friend of his father’s, an architect called Ricardo Echave, whose notes, in turn, are found by a subsequent character. Echave analyzes the style of the diaries. “It’s not difficult,” he writes, “to discover the influence of Luis Goytisolo: those long series of sentences” with

new extended metaphors, secondary metaphors that, more than centering and sharpening the initial comparison, expand it and even invert its terms, not without first laying the foundation for new subordinate associations, not without first establishing new conceptual relationships not necessarily similar to one another, new associations with the same colloidal appearance as the mercury and brimstone that alchemists mix together.

The reader, whether of the diary itself or Echave’s notes, might be inclined to agree with this description of Goytisolo’s style; perhaps the author too might see the truth in it, whether the author be the writer of the diaries, or he who penned the notes on the diaries, or even, if the idea is not too far-fetched, the actual writer who wrote the brilliant, uneven, daring tetralogy, and whose name appears on the copyright page.