In 1977 the Taiwanese director Edward Yang (Yang Dechang) was nearing thirty and working as a computer designer in Seattle. As a young man he’d dreamed of making films, but to please his parents he studied electrical engineering in Taiwan and then became one of the thousands of young, upwardly mobile Taiwanese to study in the US, completing a master’s degree at the University of Florida in 1972. A semester of film school in Southern California the following year left him disheartened, and soon he dropped out and took a position at the University of Washington’s Applied Physics Laboratory, where he would remain for the better part of a decade. “On my thirtieth birthday,” he recalled in one interview, “I suddenly said to myself, ‘Damn, I’m getting old!’ I realized that I had to change my life.”

On a drive through downtown Seattle, Yang stumbled upon a screening of Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972), Werner Herzog’s epic about Spanish conquistadores searching for El Dorado in the Peruvian jungle. “I went in and that turned me around,” Yang said. Herzog’s film—shot entirely on location and with a minuscule budget—became a touchstone of the New German Cinema, a loose grouping of young filmmakers whose aesthetically ambitious and socially conscious works upended the West German film industry. In 1981 Yang moved back to Taiwan, where he helped initiate another cinematic new wave—what came to be known as the Taiwan New Cinema. Many directors associated with the movement went on to find success abroad, including Yang’s closest contemporary and occasional collaborator, Hou Hsiao-hsien, and younger figures like Ang Lee and Tsai Ming-liang. The films they made varied widely, but they shared a visual vocabulary of extended takes, long-distance shots, and largely stable cameras; a patient attention to everyday life; and a willingness to confront the divisions in their society, both past and present.

Yang completed seven features before his untimely death in 2007, at the age of fifty-nine, from colon cancer. Almost all of them are sweeping ensemble dramas set in the churn of Taipei. Yet a pair of retrospectives at Film at Lincoln Center in New York and the Harvard Film Archive in Cambridge demonstrate how dramatically their style and sensibility shifted over the decades, from the cool urban alienation of early films like Taipei Story (1985) and Terrorizers (1986) to the madcap comedy of his middle period to the quiet, philosophical weight of his last film, Yi Yi (2000), a family saga for which he received the Best Director Award at Cannes. The series also mark how decisively Yang departed from his peers. Unlike Hou, for example, who often depicted the effects of rapid modernization on Taiwan’s rural communities, Yang more often looked outward, at how Taiwan came to assume its distinctive place in the world.

He moved back to Taiwan at the beginning of a turbulent period. In 1979 the Carter administration formally recognized the People’s Republic of China on the mainland and withdrew its support from Taiwan’s authoritarian government, which had ruled the island ever since Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist forces retreated there in 1949, after the end of the Chinese Civil War. That shock was followed by a period of political liberalization, culminating in the lifting of four decades of martial law in 1987 and the first democratic election for president in 1996. Young Taiwanese filmmakers used this opening to consider previously taboo subjects, such as the Nationalists’ violent suppression of the local population (which comprised Hokkien- and Hakka-speaking Han Chinese immigrants who preceded the Nationalists, as well as the many indigenous groups that long preceded both). Yang’s body of work in particular follows Taiwan from authoritarianism into democracy, and then from the explosive economic growth of the 1990s into the identity crises that followed. His films approach these changes through everyday stories of love, work, and family as experienced by Taipei’s emerging middle class.

Yang was born in 1947 in Shanghai, where his parents worked for a state-owned bank; when the company evacuated to Taiwan two years later, he and his family joined the approximately one million soldiers, civil servants, and civilians displaced to the island. Many waishengren (or “mainlanders,” as those who arrived in Taiwan after 1945 came to be called) spent their first decades there in suspension, the government operating in constant military preparedness to retake the mainland. Their status lay somewhere between refugees and colonizers, and they found themselves resented by many locals for their perceived closeness to the regime.

Still, Yang felt “very lucky to have grown up in Taiwan,” as he said in an interview from 2004, given the diverse cultural resources available to him there. Having been occupied by Japan between 1895 and 1945, Taiwan retained the influence of its former colonizers; Yang was fascinated from an early age with Japanese manga, especially the works of Osamu Tezuka, the creator of Astro Boy, and remained a talented illustrator throughout his life, often drafting his own storyboards, costume designs, and character sketches. The US maintained a strong military presence in Taiwan throughout the cold war, with thousands of troops stationed across the island, and Yang became immersed in American rock music, frequently tuning in to the armed forces radio station. And in a bid to garner approval abroad, the Nationalists imported films from all over the world and screened them at dedicated cinemas during Yang’s childhood. “You could watch French, Italian, Japanese, American films every day of the week,” Yang remembered. “You could see virtually anything.”

Advertisement

Before the 1980s, however, Taiwanese studios had made mostly martial arts pictures, romances, and the “healthy realist” films promoted by the Nationalists: melodramas depicting beaming farmers and promoting traditional values. But because younger audiences increasingly preferred movies imported from Hong Kong and Hollywood, the Central Motion Picture Corporation (CMPC), Taiwan’s main state-run studio, began to seek out new talent. Upon his return, after a stint writing a screenplay for a friend, Yang was recruited by the CMPC, first to direct a television drama and then to collaborate on an anthology film with other rising directors, released in 1982 as In Our Time and structured around the four stages of life: childhood, adolescence, young adulthood, and maturity.

The second chapter of the film, Yang’s Expectations, is a closely observed account of a teenage girl’s coming of age: she gets her first period, witnesses her elder sister’s dalliances, and feels a growing sexual attraction to her family’s new tenant. Perhaps as a result of Yang’s late start, a sense of assured unhurriedness permeates even this early film. The anthology ushered in an extraordinarily prolific and collaborative period for Taiwan’s new guard, with other anthologies soon following and solo projects granted to unproven directors, who congregated at Yang’s house for screenings of works by Nagisa Ōshima, Pier Paolo Pasolini, and other international auteurs.

Yang’s first three theatrical features—That Day, on the Beach (1983), Taipei Story, and Terrorizers—established him as one of the great filmmakers of urban space. For That Day, on the Beach, he gathered young stars like Sylvia Chang and hired the cinematographer Christopher Doyle, soon to be legendary for his work with the Hong Kong director Wong Kar-wai. A celebrated concert pianist, Weiqing (Terry Hu), returns to Taiwan from Europe for the first time in more than a decade and meets with her ex-boyfriend’s younger sister, Jiali (Chang). In the flashbacks that follow, we learn about the two women’s struggles against Taiwan’s paternalistic structures, including Weiqing’s rejection by Jiali’s brother, who opted for their father’s approved match, and Jiali’s own rejection of her family’s customs and her subsequent, faltering marriage to a college classmate.

Yang had at one point aspired to become an architect, and part of his genius, as early as That Day, on the Beach, was his ability to find counterparts to his characters’ domestic dramas in their surroundings—in this case the outdated Japanese decor of Jiali’s family home, or the telephone wire that bisects a shot of her and her soon-to-be-estranged mother against a hazy city backdrop. Doors, windows, and the grids of streets and buildings frequently orient his scenes; his signature shot is of two or more characters separated by a doorframe, their physical isolation from one another bespeaking larger social, romantic, or intergenerational chasms.

Taipei Story centers on Chin (the pop star Tsai Chin, who later became Yang’s first wife), a young Taiwanese woman who works for a real estate developer, and her longtime boyfriend, Lung (Hou, who also cowrote and helped finance the film), a former baseball player who has taken over his family’s fabric store. It opens with a long sequence of the couple touring an empty apartment and flitting impassively through its doorways, foreshadowing their impending separation. Over the course of the film they contend with Chin’s father’s mounting debts, try to revive their cooling relationship, and contemplate emigrating to Los Angeles. As Lung clings to a more familiar way of life, Chin turns toward the contemporary world.

Taipei itself reflects their struggle to reconcile tradition and modernity in the contrasts between the brightness of Chin’s apartment and the dimness of her parents’ house, and between her corporate office in the recently developed East District and Lung’s shop in the traditional West. New constructions rise throughout the city. “Look at these buildings,” Chin’s colleague, an architect, tells her as they gaze out over the landscape, busy with cranes and newly broken ground. “It’s getting harder for me to tell which ones I designed and which ones I didn’t.”

Advertisement

In Terrorizers these same buildings become increasingly impersonal settings for collisions among strangers. The film begins at dawn, with a shoot-out in the street between the police and what might be either a gang or a terrorist cell. A teenage photographer hears the gunshots, scrambles downstairs, and takes a picture of the one person who escapes from the altercation: a girl about his age, her leg broken. The next sequence shows a couple who seem unrelated to the previous scene: Yufen (Cora Miao), a novelist struggling with writer’s block, and Lizhong (Lee Li-chun), her aloof husband. The series of events connecting these disparate characters begins at random, when the girl, bedridden from her injury and making prank phone calls, rings Yufen, claiming to be Lizhong’s mistress.

In Taipei—a city that has been transformed from indigenous settlement to Qing outpost, Japanese model colony, provisional capital, and finally hypermodern global metropolis—the effects of history show themselves readily yet also hide beneath the surface. Yang’s characters often sit in the backs of taxis or drive themselves around the city, where they might occasionally pass Chiang’s gleaming visage or a remnant of the city’s Qing-era walls, razed by the Japanese to make way for Haussmann-derived boulevards. So many of Taipei’s buildings look alike because they were built in a hurry, between the 1970s and 1990s, when the Nationalists tacitly abandoned their plan to retake the mainland and made Taiwan their permanent home, culminating in the demolition of the shantytowns and soldiers’ villages set up as impromptu residences and their replacement with high-rises. The city has stood ever since as both a repository for nostalgia and a monument to forgetting.

After Chiang Kai-shek’s son, Chiang Ching-kuo, lifted martial law by presidential order in 1987, Hou’s A City of Sadness (1989) became the first Taiwanese film to address the February 28 incident of forty years earlier, when Nationalist troops massacred Taiwanese who had risen up against the newly arrived regime. Hou’s success at the Venice Film Festival, where A City of Sadness won the Golden Lion, marked the Taiwan New Cinema’s debut on the world stage. Yang soon followed with his own project revisiting the past.

A Brighter Summer Day (1991) is not just Yang’s only historical film but also his most autobiographical, a four-hour-long epic set in late 1950s and early 1960s Taipei that evokes the atmosphere of his childhood under martial law. It follows a group of teenage delinquents as they attend night classes, get into scraps with other street gangs, and obsess over American rock music: Frankie Avalon, Ricky Nelson, and above all Elvis Presley. At the film’s center is Xiao Si’r (Chang Chen), the youngest in a family resembling Yang’s own: Shanghainese émigrés who fled the mainland alongside the Nationalists.

“For any urban youngster, the atmosphere of the society was very oppressive,” Yang told the New Left Review in 2001. “You didn’t have to have any particular political ideas to feel this—it was all around you: rules and regulations, attitudes and institutions were authoritarian at every level.” Xiao Si’r’s night school is run by tyrannical teachers who mete out arbitrary punishments. Many of the mainlanders have been bivouacked in houses previously occupied by the Japanese colonialists, where they find samurai swords and mementos of ritual suicides. Military vehicles and uniforms are ubiquitous. “The typical phenomenon,” Yang explained, “was outward conformity and inner rage.” The turf wars among young people reflect the sanctioned violence of the state: in a sequence that plays out during a typhoon, Yang cuts between a gangland massacre and the interrogation of Xiao Si’r’s father during the White Terror, the Nationalists’ extrajudicial persecution of dissidents and critics.

In this suffocating climate, the only escape is American pop music. An extraordinary scene shows a band of teenagers performing “Why?” by Frankie Avalon and “Angel Baby” by Rosie and the Originals at the local ice cream parlor. There’s a Buddy Holly look-alike on guitar, a greaser front man named Deuce, and the diminutive, falsetto-voiced Cat, who needs to stand on a crate to reach the microphone. A Brighter Summer Day encapsulates Yang’s own conflicted feelings about American influence: the music in which he found liberation came from the same country that spent decades propping up Chiang’s despotic anti-Communist regime. In the band’s earnest performance you can hear both misplaced nostalgia and an unwillingness to be relegated to any sort of periphery. Even as the film marches toward violence—its story focuses on the first murder committed by a teenager in Nationalist Taiwan, an incident that shocked the island—songs of love and longing give it a bittersweet soundtrack.

“Curiously you could say the 70s and 80s were in some ways a better time than the 90s, when formally Taiwan became a democracy,” Yang noted ruefully. It was also the decade in which Taiwan’s economy—like those of South Korea, Singapore, and Hong Kong—boomed, borne along by its prized semiconductor industry, and the island reinvented itself as a fixture of the American-led global economy. As many of his college classmates became tech moguls, Yang, who had begun working in the theater, started pillorying the lifestyle of a newly rich society in plays like Growth Period (1993), a seven-act send-up of Taipei’s urban bourgeoisie. Invited to Hong Kong by the experimental troupe Zuni Icosahedron, Yang staged additional plays there, including a King Lear in which Lear’s daughters are replaced by a girl pop group.

Yang brought the intricate social choreography he developed in the theater, as well as a number of actors, to his next two films, A Confucian Confusion (1994) and Mahjong (1996), both newly restored. These features exchanged the detached, measured compositions of his earlier work for tighter medium shots and frenetic pacing. They might be called globalization farces, taking as their subject the yuppie class forming in Taipei during its swift ascent. One revolves around a TGI Friday’s, the other Taipei’s first Hard Rock Café; characters adopt English names as status symbols and pepper their dialogue with English words—in one film mainly “shit,” “who cares,” “pub,” and “fired.”

A Confucian Confusion (“The Age of Freedom” in the original Chinese) examines the business and romantic travails of a group of friends and lovers: Molly (Joyce Ni), the founder of a “culture company”; Akeem (Berson Wang), her hapless fiancé and her firm’s financial backer; Qiqi (Chen Shiang-chyi), her loyal employee and best friend; Ming (Wang Wei-ming), Qiqi’s long-term boyfriend; and a number of lackeys, foils, and stooges, including Molly’s brother-in-law, a writer who has abandoned the accessibility of his earlier, best-selling works in favor of weighty treatises, including one in which Confucius returns after a two-thousand-year absence only to be bewildered by the society he has created. In Mahjong, two sets of characters come to mirror each other: a gang of amoral Taiwanese punks and the equally amoral European and American grifters who have descended on Taipei in search of easy money. “In this world, no one knows what they want. They’ll thank you when you tell them,” Red Fish, the leader of his gang, says to his acolytes, a sentiment later echoed by Markus, a tall Brit with a receding hairline.

The merciless satire of these films is striking after Yang’s quieter and more restrained earlier work. One senses his frustration with the driftlessness of the mid-1990s, soon before the rising Asian economies imploded under the pressure of maintaining unchecked growth. Yang dubbed his own voice over that of the actor who plays Red Fish’s father, a reformed con man who advises his son that “what you want is the thing that money can’t buy.”

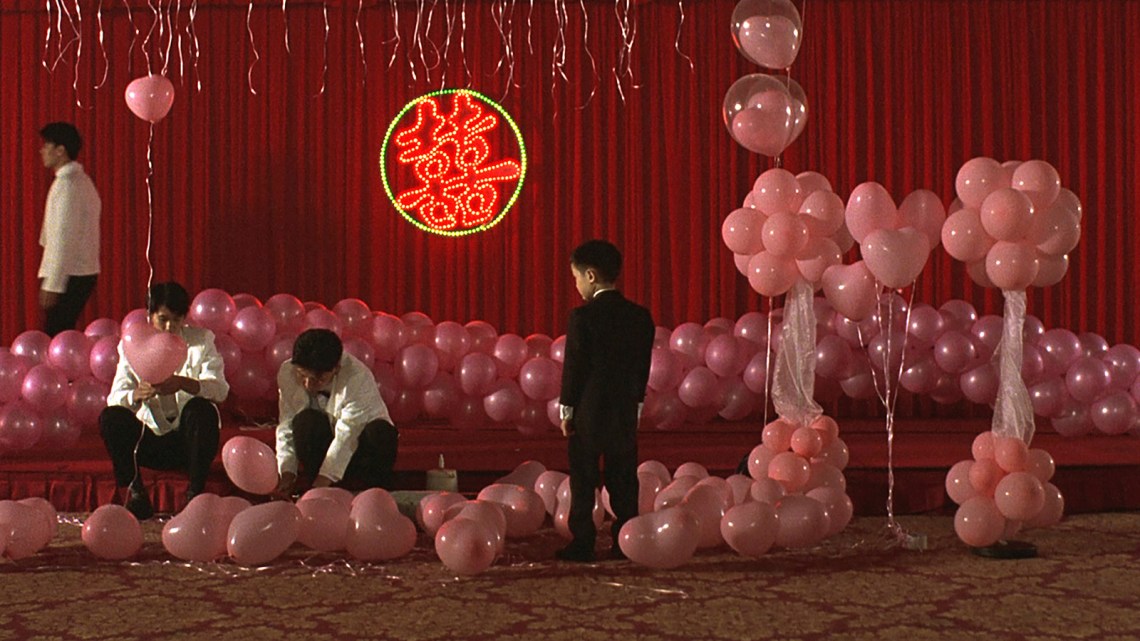

The clearest summation of Yang’s philosophy can be found in Yi Yi. The richly plotted film, which spans three hours and includes a large ensemble cast, begins at a wedding, ends at a funeral, and takes in much of life in between. It concerns three generations of the Jian family: NJ (the screenwriter and director Wu Nien-jen), a decent but beleaguered father, who reunites with an old flame while his computer company is struggling; Min-Min (Elaine Jin), the mother, who experiences a spiritual breakdown and moves into a monastery; Ting-Ting (Kelly Lee), their teenage daughter, who becomes involved in a neighbor’s relationship troubles; Yang-Yang (Jonathan Chang), their eight-year-old son, who has an artistic awakening; and Min-Min’s mother, who suffers a stroke at the beginning of the film. Doctors direct the Jians to continue speaking to her even though she can’t respond, and as each family member unloads their private burdens at her bedside, Yang shows how our lives can intersect but never fully overlap even with those of the people closest to us.

He does this by intimately following each character’s trajectory, preserving the privacy of their interactions with long-distance shots, and giving the actors space to express themselves in extended takes. (The film is anchored by immaculate performances by Lee and Chang, both nonprofessional actors in their first roles.) Even separate lives spill into each other. Sounds from one scene wash into the next: a computer programmer predicting the course of artificial intelligence over an ultrasound of a fetus, or NJ’s nostalgic reunion with his first love overlapping with Ting-Ting’s first murmurings of romance and heartbreak. The film is preoccupied with repetitions and doublings; many of its scenes are either shot through translucent glass or captured on reflective surfaces, as when Min-Min gazes out at the city at night, a red light flickering over her heart. In Chinese, the film’s title—roughly translated to “A One and a Two” in English versions—consists of two strokes of the character for the number one, “一”. When placed directly above one another, they form the character for two, “二,” indicating how a larger meaning can arise from isolated parts.

What results is a composite portrait of Taipei as it prepared to enter the twenty-first century. One remembers Yang’s background as an engineer, not only in NJ’s profession but also in the very structure of the film, which carefully fits disparate pieces into a complete whole. Even when Yang’s eye is detached, however, it is never dispassionate. At one point the precocious Yang-Yang asks his father how we can be certain that we’re sharing the same world as other people. If “I can’t see what you see, and you can’t see what I see,” he wonders, “can we only know half of the truth?” When NJ doesn’t provide an answer, Yang-Yang embarks on a project to photograph the backs of his friends’ and relatives’ heads. “You can’t see it yourself,” he explains, “so I show it to you.”

Despite its success abroad, Yi Yi did not receive a theatrical release in Taiwan until 2017. Throughout his career Yang chafed at his domestic reception, which he attributed partly to the public’s commercial inclinations and partly to his outsider status. “A lot of people have tried to brand me as a mainlander, a foreigner who’s somehow against Taiwan,” he said in 2001. “But I consider myself a Taipei guy—I’m not against Taiwan, I’m for Taipei.”

Some of that oversight was rectified by an extensive exhibition at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum last year (cocurated by the museum’s director, Wang Jun-jieh, and the film scholar Sing Song-yong) and organized alongside the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute, where Yang’s widow and frequent collaborator, the concert pianist Kaili Peng, deposited his vast archives in 2019. The exhibition included unpublished letters and diaries, unfinished screenplays, and souvenirs from various productions. What came across immediately was the scope of Yang’s influences. Remarkably, nearly half the documents displayed were in English. Featured were his sizable collection of records (Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Jimi Hendrix, Elvis) and photographs of Yang in the sports paraphernalia (49ers hats, Seattle SuperSonics jackets) that he would wear until the end of his life.

Viewing the exhibition, I wondered why Yang returned to Taipei when he decided to become a director. His work is packed with the consequences of coincidence, the specters of paths not taken; Yang, who became an American citizen during his decade in the US, might have stayed in the country and become a filmmaker here. Yet one senses that, like Yang-Yang, he felt a greater need to document the back of things. “There are many like me in New York, or San Francisco, or Seattle, or Gainesville, Florida; there are also many more in Tokyo, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Seoul,” Yang noted to the film critic John Anderson in 2001. “We are not Americanized; before we are anything, we are just human beings living in the twenty-first century. We have open arms, to receive as well as to give.”

This Issue

March 7, 2024

Circuit Breakers

‘She Talk Her Mind’

Ready to Rumble