James Wong Howe had a talent for making things darker. In the early 1920s, the orthochromatic film used in Hollywood was oversensitive to blues, resulting in features like washed-out skies. Mary Miles Minter, a leading actress of the silent era, had bright blue eyes which would appear blank when filmed. As a twenty-three-year-old camera assistant, the young Wong Howe hit on the first of many innovations that would define his long and fruitful life in show business: framing the lens in a curtain of black velvet, so that Minter’s eyes would reflect the darkness. Word got around that Minter had “imported herself an Oriental cameraman—he hides behind black velvet and he makes her eyes go dark,” as Wong Howe later recounted. Soon, every blue-eyed actor and actress was requesting his services.

This breakthrough inaugurated a career that would span fifty-eight years and more than one hundred and thirty films. Often named as one of the greatest cinematographers of all time—and certainly the most versatile and expressive of the black-and-white era—Wong Howe worked with directors including Howard Hawks, Victor Fleming, Fritz Lang, Martin Ritt, and John Frankenheimer, and shot leading stars from Spencer Tracy and Cary Grant to Myrna Loy and Barbra Streisand. He pioneered the use of techniques like deep focus and high-contrast lighting; his dexterity at sculpting scenes of rich chiaroscuro garnered him the nickname “Low-Key Howe.” Weathering changes in Hollywood from the advent of sound to color to widescreen, Wong Howe won two Oscars (for 1955’s The Rose Tattoo and 1963’s Hud) and was nominated for eight others.

The fact that a Chinese cameraman—Wong Howe was only naturalized in his forties, after the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1943—had such a large hand in shaping the fantasies of the American public was surely lost on audiences who did not look for the cinematographer’s credit. Part of this omission can be attributed to a lack of understanding about the role of the cameraman, who exerted a control equal and often superior to that of the director in defining the look of Golden Age films. Yet another factor was Wong Howe’s versatility. Unlike other cinematographers of the era, such as John Alton, Wong Howe was never associated with one genre, as adept at noir and westerns as at musicals and comedies. He adapted his style to suit the needs of different directors and scripts, to the point where an undiscerning viewer might deem it more assimilative than personal.

A timely, illuminating retrospective at the Museum of the Moving Image—which has brought together nineteen of Wong Howe’s works, many in luscious 35mm prints—will assert without a doubt that he was an artist in his own right. Whether audiences knew it or not, they were seeing things as Wong Howe saw them.

*

James Wong Howe was born Wong Tung Jim in Guangdong in 1899. At five, he was brought to Pasco, Washington, where his emigrant father worked his way up from laboring on the Pacific railroads to running the local general store. As one of the few Chinese in town, Wong Howe wore a Qing-era queue and bribed neighborhood children to play with him. His first teacher resigned rather than teach a “Chinaman”; his second helpfully anglicized his name, when she mistook his father’s given name, “How,” for his surname.

Wong Howe’s early ambitions were to be an aviator or a prizefighter, professions he would memorialize in works like Howard Hawks’s Air Force (1943) and Robert Rossen’s Body and Soul (1947). One can imagine the young Wong Howe confronting petty prejudices and considering fight or flight. Instead, he settled on photography, landing a job in a Los Angeles photo studio, finagling his way into Famous Players-Lasky (the studio that would become Paramount Pictures) as a janitor, and eventually holding the slate for Cecil B. DeMille, who was reportedly amused by the five-foot-three Wong Howe, wearing a Hawaiian shirt and smoking a fat cigar during takes. Often the last to remain on set, Wong Howe would spend his nights on Gloria Swanson’s stage bed and practice cranking a camera with a coffee grinder.

In the 1920s, the cinematographer was a powerful position. The Hollywood studio system had by then come to function like a factory floor, with the cameraman its chief technician: in charge of large teams of electricians and operators, all of the lighting, and often the lens choices, angles, and camera movement as well. Given the mercurial technology, successful cameramen were also distinguished by their ability to experiment, and Wong Howe’s penchant for imaginative solutions—coaxing a canary to appear to sing by sticking gum to its beak, darkening Minter’s eyes with velvet—would land him his first gigs as chief cameraman, on the Minter features Drums of Fate (1923) and The Trail of the Lonesome Pine (1923).

Advertisement

Wong Howe gained a reputation as a glamour photographer—one that would remain throughout his career, given his ability to shoot actresses at their best with minimal intrusions from diffusive effects—but from his early films that ability to glamorize was tempered by an easy realism. In Victor Fleming’s Mantrap (1926), an agreeable farce about a fur-trapping town, Wong Howe’s approach to shooting the many outdoor locations produced elegant, almost impressionistic sequences. On a trip to China in 1929, however, Wong Howe missed the disruptive transition to talkies, and when he returned to Hollywood he was unable to find a job. The sound man was the new boss in town.

After a year without work—Wong Howe’s biographer, Todd Rainsberger, describes him pushing his Duesenberg roadster down hills to save gas—he made his comeback with the 1931 Transatlantic, in which he used deep focus a decade before Gregg Toland employed it so famously in Citizen Kane (a film Wong Howe found showy). For this murder mystery set on a cruise ship, Wong Howe created an air of claustrophobia with ceilinged sets and rocking cameras, as well as what would become his signature aesthetic: dramatic shadows cut through with beams of light.

In the 1930s and 1940s, Wong Howe used this low-key style to tremendous effect, first for Fox and MGM, then for Warner Brothers. Despite studio-mandated restrictions, he accentuated the setting of pictures like The Thin Man (1934) and The Prisoner of Zenda (1937) with lighting that presaged the noir films of the 1940s, with torch- and gas-lit compositions, pools of light, and dark, ominous nooks and crannies visible in the frame. (In Zenda, Wong Howe even gave the latter a touch of special effects, with a double exposure allowing the same actor to play two roles and shake hands with himself.)

Wong Howe considered mood paramount, and often consulted before a shoot not only with the director but also with the art director, set designer, and even costume designer. This perfectionism comes through in the atmospheric camerawork of films like Kings Row (1942), in which Wong Howe used dense shadows and expressionistic angles to reveal a picturesque midwestern town’s hypocrisies and the madness and sadism hiding underneath them. (Ronald Reagan’s line in that film, after his legs are needlessly amputated—“where’s the rest of me?”—would help make him famous, and furnish the title of his 1965 memoir.)

Wong Howe’s biographers and interlocutors often note his reticence to talk about race or his political views. Rainsberger, in his exhaustive and insightful—if oddly restrained on these matters—1981 study, even claims that Wong Howe was largely apolitical. Yet the limitations of Wong Howe’s world were inescapable. Many crew members refused to work under a Chinese cinematographer. During World War II, Wong Howe was forced to wear a pin declaring himself Chinese, not Japanese. Although he was offered a job in John Ford’s documentary corps in the Pacific, his citizenship status rendered him ineligible for it. After the war, he found himself “graylisted” by the House Un-American Activities Committee on suspicion of his political leanings and his friendships with figures including James Cagney, John Garfield, and Rossen, many of whom would ultimately be blacklisted.

The combination of acceptance and exclusion, invisibility and notoriety that Wong Howe suffered throughout his career fashioned his lens. One can see it, for example, in the many films that Wong Howe made with Garfield, from the boxing flicks They Made Me a Criminal (1939) and Body and Soul to the B-noir He Ran All the Way (1951). How he shot Garfield’s working-class hero—both pugilistic and honorable, animalistic and sensitive—and the characters around him, mired in the corrupting influences of money and greed, make it clear on which side Wong Howe’s camera lies.

In 1947, Wong Howe’s contract with Warner Brothers ended, and he would freelance for the rest of his career, choosing his own projects. If there is a James Wong Howe style, it comes across most clearly in this intensely productive period of the 1950s and 1960s.

*

Wong Howe had a deep mistrust of the prettified glamour of studio films. Rather than countering with a pedantic naturalism, however, his style more closely resembled a poetic realism: a faith in simplicity coupled with a qualified embrace of artifice. This often involved a documentary instinct, as in Body and Soul, where he famously entered the ring with roller skates and a handheld camera to embody the toll of a fight. He indexed the styles of contemporaries like the Italian neorealists and precursors like the German expressionists, while formulating them into one unmistakably his own. His wife, Sanora Babb, said that his admirers called him a “poet of the camera.”

Advertisement

Much insight into Wong Howe’s style can be found in his long marriage to Babb, the leftist activist and writer whose reports on Oklahoman refugees may have supplied material for John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, and whose own Dust Bowl novel, Whose Names are Unknown, remained unpublished until 2004. The two were unofficially married in Paris in 1937, but were unable to be legally recognized until anti-miscegenation laws were repealed in the state of California. Theirs was an equal partnership, in matters artistic (collaborating on unrealized scripts), commercial (running a Chinese restaurant in Los Angeles), and even combative (when two men dumped Wong Howe and Babb out of their chairs at a dinner Wong Howe was giving for the Italian star Anna Magnani, Wong Howe slugged one while Babb jumped on the other’s back). They shared a belief in the necessity of starting from one’s own observations. “If I do a thing one way, it does not follow that it is what John Seitz, or Karl Struss, or George Barnes would do,” Wong Howe wrote in an essay for the 1931 Cinematographic Annual. “It does not follow that my way is the only way: it is simply the method that my experience and my personal inclinations suggest.”

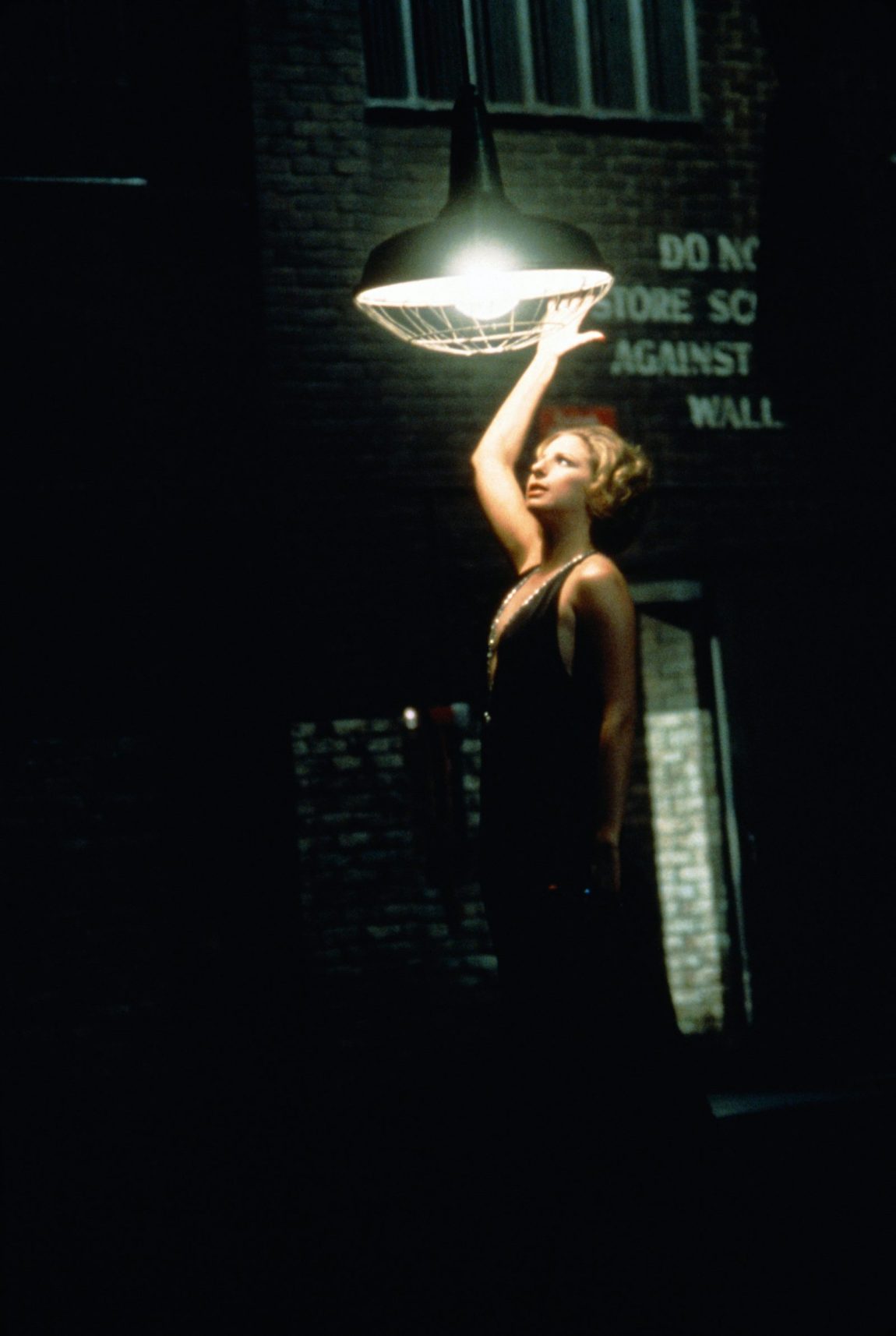

What made Wong Howe a consummate artist was his ability to cohere his experiences into a visual style, to make a viewer feel as he felt, especially in later works like Hud (1963) and Sweet Smell of Success (1957). For the moody, psychologically complex western Hud, he erased any trace of clouds to arrive at the bleakness of an empty Texas sky. In Sweet Smell of Success, perhaps Wong Howe’s most lasting and influential film, his frantic, high-contrast depiction of New York resembled the tabloid photographs of Weegee, conjuring a hungry, uncaring city suited to the film’s story of a power-hungry gossip columnist and his unscrupulous sidekick. Wong Howe oiled the walls to make them shine and shot Burt Lancaster’s columnist, the bespectacled J. J. Hunsecker, with his eyes recessed in shadows. He painted settings that could train glaring lights on you in one moment, and then smother you in darkness at another.

The advent of color was difficult for Wong Howe. “Color gives a certain falseness to me,” he told an interviewer late in his career. “You see it concentrated and emphasized on the screen, unlike life.” Early color films tended toward unrealistic brightness. Wong Howe was able to use color fruitfully in Picnic (1955), however, when the newcomer director, Joshua Logan, gave him license over the visual decisions. A small town in Kansas is shaken up by the appearance of the swarthy William Holden, and one can sense every eye on the stranger. Wong Howe gave his portrayal of Americana a sunset palette, in the shots of a Labor Day picnic’s orgy of whiteness (pie-eating contests, three-legged races) and of the film’s denouement, on a lakeside wharf lit by paper lanterns (a decision made singlehandedly by Wong Howe).

Perhaps Wong Howe’s most striking work was on John Frankenheimer’s psychological horror film, Seconds (1966), about a disaffected suburban banker enticed by a shadowy organization to receive plastic surgery, fake his own death, and emerge into a new life. Wong Howe used body-placed cameras, extreme wide-angle lenses, and high contrast to evoke an eerie, out-of-body disorientation, no doubt drawing on his own experiences of disassociation (and likely the star, Rock Hudson’s, as well, as the world would discover when he died of complications from AIDS in 1985).

Although Wong Howe often collaborated with directors who knew what they wanted, like Hawks and Ritt, he produced much of his best work with ones who gave the cameraman free rein on set. His relationship with Frankenheimer was productive, if testy, largely because Frankenheimer augured a new generation of directors who attended film school and involved themselves intimately in the camerawork. “John Frankenheimer is a young, brilliant director; but he hasn’t gotten away from this fascination with the camera and his eagerness to use it,” Wong Howe told Alain Silver in Silver’s 1969 oral history (published in 2010 as The Camera Eye). The director had become the “auteur” of a film, although no major Hollywood studio would let a Chinese-American direct for many more decades. The irony of Wong Howe’s career was that he could only have risen to prominence in a pre-auteur world; his genius, and limitation, was to slip in his own perspective through the guise of the technician. “Secretly he knew he was a lot more than a technician,” Babb recalled. “I tried to tell him it wasn’t a disgrace to be an artist. I think he was just embarrassed!”

*

Until his death in 1976, Wong Howe dreamed of making a film in China. On a preliminary trip in the 1920s, he filmed documentary scenes which would make it into Josef von Sternberg’s Shanghai Express (1932). In 1949, he was shooting in Beijing when the Communists took over. For that film, a planned adaptation of Lao She’s social realist novel Rickshaw Boy (1937), he had intended to observe rickshaw pullers directly. “There are many fine stories just waiting to be put on film,” he told an interviewer,

stories of the folk who live on river boats and spend their lives drifting down the waterways of China, stories of the farmers living close to the land and drawing life from the soil. We will film stories like these, not on sound stages with artificial sets and props, but in actual locales where we can capture realism and the flavour of the country itself.

That film was never made. One can sense the palpable lack of interest in the American public for watching a film that documented the “flavour of the country” with clarity and tact. This was, after all, the same era as whitewashed productions like Dragon Seed and The Good Earth, Charlie Chan and Fu Manchu. In his later years, Wong Howe tried to produce a film about San Francisco’s Chinatown, which similarly ran out of backers and funding.

His sole feature-length directorial credit was for Go, Man, Go (1954), a film about the Harlem Globetrotters and the team’s founder, Abe Saperstein, playing at MoMI in a rare print. Although that film, written by the soon-to-be blacklisted Alfred Palca, has its moments of grace, such as a scene with the eccentric musician Slim Gaillard, one can sense Wong Howe chafing at his own reputation for efficiency (which likely contributed to his being asked to direct the film in twenty-one days and on a budget of $130,000). He surely identified with the Globetrotters, never taken seriously despite, or because of, their showmanship. (Their race is never explicitly mentioned in the film, even though it is the obvious reason why they are kept out of the national league.)

Wong Howe was never given the chance to write a script; he rarely edited his own work. In the brief documentary he made for his own short-lived independent production company about the Chinese-American watercolorist Dong Kingman, one can sense Wong Howe’s envy of the painter’s freedom, his ability to finish a painting, untroubled, in the comfort of his own home and to color it as he wished. Yet if we now recognize the “otherized” depictions of the Chinese in films of the era—the hypersexualized women, the eunuch men, the pidgin English, the whitewashing—as reflections of the desires and delusions of their creators, then Wong Howe accomplished something much rarer: changing the perceptions Americans had of themselves, by reflecting them back the way he saw them.