“Does Harry Smith really exist?” So the writer and filmmaker Jonas Mekas began his March 18, 1965, column for The Village Voice. “For years,” Mekas wrote, Smith had been “a black and ominous legend and a source of strange rumors. Some even said that he had left this planet long ago—the last alchemist of the Western world.” This hyperbole is bizarre but unsurprising. A tireless apostle of the movement he named the New American Cinema, Mekas had devoted much of 1963 to promoting Jack Smith (no relation), whose banned Flaming Creatures became a cause célèbre, then a good deal of 1964 to extolling Andy Warhol’s switch from Pop Art to underground movies. Harry Smith was a new film genius to support, albeit a difficult one. Smith is “very brilliant, very learned,” Mekas noted in his diary, but also “crazy, evil, nasty,” and even abusive. “I don’t know how I managed to make him show his films.”

Harry Everett Smith, who died at age sixty-eight in 1991, has officially arrived. His centennial was marked by two firsts: the publication of the first biography on him, John Szwed’s Cosmic Scholar, was complemented by “Fragments of a Faith Forgotten,” a half-floor exhibition of films, paintings, and artifacts at the Whitney Museum, the first major museum show devoted to his work. The title, a phrase sometimes used by Smith, comes from a book on gnostic texts by the British theosophist G.R.S. Mead.

At once famous and obscure, marginal and central, Smith anticipated and even invented important elements of the Sixties counterculture, most obviously with his idiosyncratic six-LP Anthology of American Folk Music, issued by Folkways Records in 1952, which provided a basis for the folk music revival of the early 1960s. Less known are the homemade light shows Smith contrived circa 1950 for a San Francisco jazz club. More general inspiration may be found in his abiding interest in Native Americans, arcane spiritual knowledge, and fondness for hallucinogenic drugs. The headline for the New York Times art critic Holland Cotter’s review of the Whitney show identified Smith as a “shaman,” and Szwed describes the tiny basement apartment in the Bronx where Smith lived in the early 1950s as something like the original hippie crash pad—“an atelier with DayGlo paint and black lights, ‘alchemical’ substances bubbling on the stove.”

Smith was also unique. The impossibly labor-intensive handmade animations that Mekas found so extraordinary—in particular No. 12, a sixty-six-minute series of animated hieroglyphs that suggests a vaudeville Jules Verne version of The Tibetan Book of the Dead as enacted by a cast of dismembered Victorian valentines and cutout figures from a nineteenth-century Sears, Roebuck catalog—are the products of a one-man counterculture. Before they made Harry (to steal a joke), they broke the mold.

Indeed, Smith is scarcely easier to characterize, let alone explain, than he was when Mekas took up his cause in the mid-1960s. An almost absurdly polymathic autodidact, generally self-medicated, supposedly sexually abstinent, this scholar/collector/artist/inventor turned amateur anthropologist was for much of his life indistinguishable from a derelict, surviving largely on handouts, tarot readings, and research gigs commissioned by fellow occultists. Szwed, himself an anthropologist and lover of jazz and the author of books on Billie Holiday, Miles Davis, and Sun Ra, has set himself a formidable task. In the introduction to Cosmic Scholar, he confesses thinking that he’d “never again encounter anyone as mysterious and undecipherable as Sun Ra.” Then “along came Harry.”

He was a product of the Pacific Northwest, raised on the shores of the Salish Sea, who zigzagged Zelig-like through a series of bohemian scenes: the Berkeley Hills, San Francisco’s Fillmore District, New York’s East Village, the Chelsea Hotel, and, late in life, Boulder, Colorado (where in 1988 Allen Ginsberg contrived to get him an appointment of sorts at the Naropa Institute). Periodically he would disappear into flophouses or take detours to hang out with the Kiowa in Oklahoma or the Seminole in Florida.

Smith was a natural fabulist. Szwed’s biography—drawing, in the absence of a substantial paper trail, largely on interviews with Smith’s younger friends and associates—has the quality of a tall tale. Paradoxically, however, Smith’s hitherto unknown youth has been illuminated by both Szwed’s research and that of Bret Lunsford, a musician based in Anacortes, Washington, where Smith lived from age nine to nineteen. Lunsford’s Sounding for Harry Smith, an obsessively detailed account of Smith’s boyhood and schooling, as well as his hometown, excavates a period of which Smith rarely spoke, save to maintain that his mother was or believed herself to be the lost Russian princess Anastasia Romanov, and that he himself was the illegitimate son of the magus Aleister Crowley.

As it turns out, Smith did have at least one semi-illustrious antecedent. His great-grandfather John Corson Smith had been a brigadier general in the Union Army and later lieutenant governor of Illinois. Harry’s father was a marine engineer who worked in different capacities at various Washington canneries; his mother was a schoolteacher from a family of schoolteachers (who had once taught at an Alaskan school for Native Americans located in a village founded by Russian colonists, hence the Anastasia connection). Both parents were readers with an interest in theosophy.

Advertisement

Harry was an isolated child whose growth was stunted by rickets; he was given art and music lessons, as well as a set of blacksmith tools that had been abandoned in his father’s cannery (and that, he would claim, came with a paternal injunction to turn lead into gold). Szwed describes Smith’s boyhood as one of “boundless curiosity, intense focus, and self-discipline.” A precocious ethnographer, Smith learned to record sound and devoted this skill to documenting the area’s Native American population. Still in high school and operating on his own, he attended spirit dances, interviewed tribal elders, conducted field studies, collected artifacts, and donated objects to the Washington State Museum. The cover of Lunsford’s book is a haunting photograph of teenage Harry in rapt concentration as he records a Lummi tribal elder.

Smith was also experimenting with photography and animation when he discovered a 1940 Bluebird 78 recording of “New Highway No. 51,” by the Delta bluesman Tommy McClennan—a raw, forcefully unintelligible performance that to a kid from Bellingham must have seemed like a message from an alien world. Smith immediately enlisted in another collector vanguard, amassing hundreds of 78s, mainly “race” and “hillbilly” records, which he appreciated for their weirdness. He briefly studied anthropology at the University of Washington in Seattle, then dropped out to work even more briefly in a Boeing defense plant, then made his way to Berkeley, where he took classes at the University of California and for the first time found a like-minded community of artists, oddballs, and record collectors.

Smith began painting, with an interest in visualizing music. He was impressed by Kandinsky’s late abstractions and theoretical writings, as well as by the abstract animations Composition in Blue (1935) and Radio Dynamics (1942), produced by the German refugee Oskar Fischinger. Along with Jordan Belson, another young artist interested in film (and a filmmaker credited with inspiring the “Star Gate” sequence of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001), Smith made nonobjective paintings and, more radically, animations created without a camera, produced by staining and scratching the film emulsion. (He was not the first to do so—Len Lye began making such films in London in the mid-1930s—but Smith developed his own laborious technique, using batik to create layers of color on clear 35mm film.) The films—percussive, pulsating organic shapes in a paint-flecked space—were shown at the San Francisco Museum of Art. Sometimes they were part of live performances. One 1950 program, Five Instruments with Optical Solo, explained that Smith’s film would “serve as the sixth instrument in a be-bop jam session…not as visualization of the music but as a basis for its departure.”

Baroness Hilla Rebay, the imperious first director of the Museum of Non-Objective Painting (now the Guggenheim) and a supporter of Fischinger’s work, visited San Francisco in 1948; Smith and Belson managed to attract her attention, and Smith secured a small grant to create three-dimensional abstract films. (None of these survived.) He was then living in a room upstairs from an after-hours jazz club in the Fillmore, San Francisco’s African American neighborhood. Smith painted the club walls with abstract motifs and projected his animations, using 78s by Dizzy Gillespie and Thelonious Monk as a soundtrack.

Eighteen years before Bill Graham took over the Fillmore Auditorium, Smith invented a form of light show that involved the projection of oils mixed on a mirror. Most likely he left this device behind when, hoping for patronage from the baroness, he departed California for New York, stopping off in Drury, Missouri, to meet with a twenty-five-year-old farmer, George C. Andrews, who shared his interest in marijuana, jazz, the occult, and UFOs.

Smith arrived at Penn Station and walked some fifty blocks uptown, presenting himself at the apartment where the twenty-seven-year-old poet-scholar-mystic Lionel Ziprin lived with his future wife, Joanna—Andrews had provided the introduction. Smith crashed with the Ziprins off and on for as long as he could, initiating a fifteen-year series of alliances, projects, and mishaps that rivals the scene-mapping plotlines of William Gaddis’s The Recognitions or Thomas Pynchon’s V.

Smith soon discovered that Rebay had lost interest in his work (as well as in her position at the Guggenheim). Unable to keep a job, without money or prospects, he drew on his formidable record collection, offering it to Moses Asch, the son of the Yiddish writer Sholem Asch and proprietor of Folkways Records. Asch had recorded Woody Guthrie and Lead Belly, released Sounds of a Tropical Rainforest, and was by then reissuing old jazz 78s. He gave Smith a small advance against royalties, a corner in his cramped midtown office, and, he said, a supply of peyote buttons to create the eighty-four-song Anthology of American Folk Music.

Advertisement

The Anthology was at once cabalistic and canonical, a collage of found material organized and annotated according to Smith’s enigmatic principles and design sense. (He spoke of it as an “art object.”) It was composed almost entirely of commercial recordings made between 1927 and 1933, a period when record companies looking for new markets recorded banjo pickers, gospel sermons, and jug bands. Relatively few copies were sold. Still, the Anthology exerted a profound influence on folk revivalists like Dave Van Ronk and John Cohen, who for years suspected “Harry Smith” to be a pseudonym (some for the musicologist Alan Lomax), and through them the young Bob Dylan, who put new words to the melodies (and vice versa).

So siloed were Smith’s accomplishments that his folkie admirers had little sense of his other work, while those familiar with his films were astonished when, now supported by the Grateful Dead’s Rex Foundation, Smith was presented with an almost posthumous Grammy in 1991. Since then, the Anthology has been several times reissued and the subject of no small amount of academic commentary. Not simply a compendium or even a taxonomy, the Anthology is an epic, intricately cross-referenced narrative played out over dozens of songs, beginning with an Appalachian murder ballad and ending with a cheerful blues song about going fishing. Like Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera or Fernando Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet, it is modernist assemblage that still seems far from understood.*

After finishing the Anthology, Smith spent his days doing research, paid and unpaid, in the New York Public Library and his nights at Birdland, where, at least at that time, his preferred drink was milk. Together with the Ziprins, he briefly went into the hip greeting card business. He also busied himself for several years recording Ziprin’s grandfather Rabbi Naftali Zvi Margolies Abulafia, a fount of Sephardic Jewish liturgical music. Smith gave Asch enough of this material for a fifteen-LP set, but for a variety of reasons Folkways was unable to clear the rights. At the same time, Smith completed his first eleven films and embarked on No. 12.

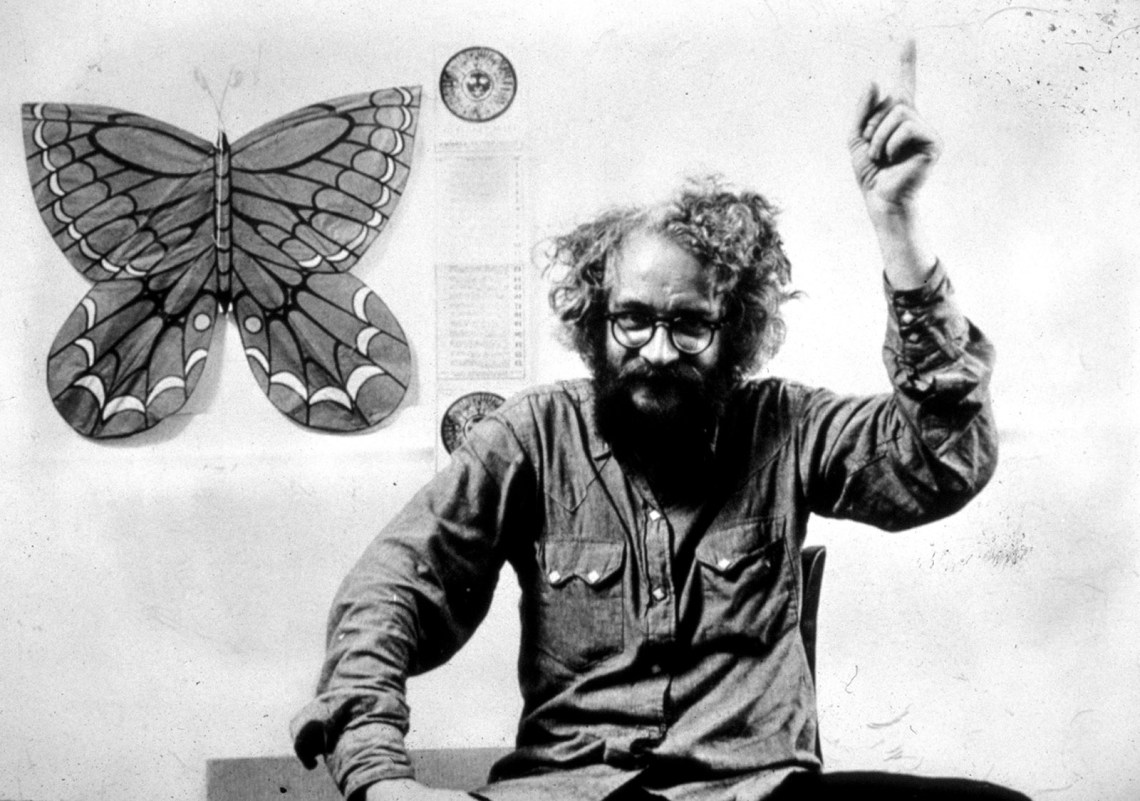

In the summer of 1958 he met Allen Ginsberg, who along with Jonas Mekas became his most loyal supporter at the Five Spot, a Bowery bar that was the hippest of downtown jazz clubs. Smith was there taking notes, attempting to ascertain how often Thelonious Monk played behind or ahead of the beat. Ginsberg was intrigued, and the two became friendly—Ginsberg enjoyed smoking pot at Smith’s tiny Yorkville apartment and looking at Smith’s movies projected on the wall, accompanied by cuts from Monk’s LP Misterioso.

Impressed with the abstract animations, Ginsberg had his mind blown by Smith’s latest, the cut-and-paste collage Film No. 12, which Smith, always in need of money, sold to him for a small sum. In 1961 Ginsberg—then friends with LSD proselytizer Timothy Leary—organized a screening for Leary’s wealthy friends to fund Smith’s latest project, an animated version of The Wizard of Oz. The principal investors included Elizabeth Taylor, the supermarket heir Huntington Hartford, and a young millionaire, Henry Ogden Phipps, whose April 1962 overdose effectively ended the project. Discovering that after a year only nine minutes of full-color cell animation had been produced—Smith was using a multiplane camera of his own design, most likely under the influence of LSD—the backers withdrew. (A tantalizing fragment is included in the Whitney show: it places W.W. Denslow’s original drawing of the Tin Woodsman, moving as though a Balinese puppet, in a luminous, somewhat lurid deep space.)

The failure of this project did not improve Smith’s disposition. He began to drink heavily. Still, offers came his way. In early 1964 he became involved in the production of Chappaqua, a psychedelic vanity project directed by and starring the twenty-nine-year-old cosmetics heir Conrad Rooks. Smith went with Rooks to Oklahoma and almost immediately ran afoul of the law: he was held for a week in the Anadarko jail for public drunkenness and suspicion of stealing guns. While in jail he met and befriended several Kiowa, who introduced him to their peyote rituals, which he taped for Moses Asch. On returning to New York, having pawned his borrowed film equipment to purchase a train ticket, he found that his landlord had evicted him in absentia and thrown his belongings—including paintings, films, books, and records—in the trash. The chronology is murky, yet it seems that, thanks to Ginsberg, No. 12 and other film material had been entrusted to Mekas before Smith left town, and by the time he returned from Oklahoma, Mekas had had a chance to look at his films. Soon after, Smith brought his special projector—a “huge contraption” Mekas called “a wooden Trojan Horse” that incorporated two slide machines as well as a movie projector, with carriages for filters and knobs to regulate the screen format—and moved into Mekas’s lower Park Avenue loft, the offices of the Film-Makers’ Cooperative.

The first public screenings of Smith’s early animations were held in October 1964 at the Washington Square Art Gallery, where Andy Warhol had recently premiered Blow Job, although there were also a few private screenings of Heaven and Earth Magic (as No. 12 was now called). Smith was impressed with Warhol, less for his films perhaps than his seeming ability to monetize them. The poet Carol Bergé saw Heaven and Earth at the East Village poetry hangout Le Metro Café and reported on it in Mekas’s journal Film Culture:

Smith, eyeglasses broken, irascible, nervous, says it was made from 1940-1960, roughly. He runs his own odd projector, mumbles clearly to the audience of mostly poets:“…this all takes place on the moon.”

Wherever it takes place, Heaven and Earth Magic pushed collage animation to the outer limits of possibility. To call the film “obsessive” scarcely does justice to the work’s fantastically hermetic quality and paranoid underpinnings.

“Consequent to the loss of a very valuable watermelon,” per Smith’s description, the heroine of the film—a Victorian woman with piled hair and a full skirt—suffers a toothache, undergoes dentistry, and ascends to heaven. Filled with rotating cogs and Rube Goldberg contraptions, this ethereal realm has a steampunk feel avant la lettre. Heaven is something of a machine—although one continually on the verge of careening out of control. At some point Smith added a soundtrack that suggests a Coney Island spook house enlivened by barking dogs and croaking frogs as well as, briefly, a carnival barker. As the heroine herself seems to lose parts of her body, a dancing homunculus attempts a series of operations to put her back together. Ultimately both are devoured by the giant head of Max Müller, a nineteenth-century philologist and editor of The Sacred Books of the East. This is the climax of the heroine’s trip: that the anesthetic has worn off is signaled by her dreamy descent to earth, watermelon—which sometimes develops a third eye or a mouth—regained, passing through a cosmos of flying salamanders and enormous snow crystals in a roomy nineteenth-century elevator.

Mekas waited until April 1965 to announce Smith’s presence on the scene, scheduling a benefit screening for the “legendary” filmmaker at the City Hall Cinema, a 576-seat house in the no-longer-existent New York Tribune Building. Thus began Smith’s brief period as a semipublic figure.

Around this time Smith found another patron, the filmmaker Shirley Clarke, who guaranteed his rent at the Chelsea Hotel. He resided there from 1965 through 1977, alienating some guests and befriending others, including Patti Smith and Robert Mapplethorpe. His room was a miniature museum housing his various collections (Ukrainian Easter eggs, string figures, and paper airplanes found on the street) and his extensive library of artbooks and occult literature. While at the Chelsea, Smith began work on a film based on the 1930 Kurt Weill–Bertolt Brecht opera Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny. By his own account, he had been listening to the 1956 German recording for years but, coincidentally or not, began talking about making a film around the time that, in a notorious fiasco, the opera was briefly staged in the East Village. He sometimes described the work as a commentary on Marcel Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even, and said that it was designed to be projected on a screen fashioned from torn newspapers or a wall of billiard tabletops.

Smith was still working on Mahagonny when he was evicted from the Chelsea and relocated to a welfare hotel on Broadway and 29th Street. Few ever expected to see the film but amazingly, supported by several arts grants, it had its premiere in March 1980 at Mekas’s Anthology Film Archives in SoHo as a two-and-a-half-hour, four-projector piece accompanied by the German recording. “To call it puzzling is an understatement,” I wrote then in The Village Voice. At a loss to decode it, I described it as “a kind of magic assemblage—subject to its own recognizable but baffling laws, incorporating Brecht’s vision of corruption into its own hermetic system of fetishes.”

Mahagonny, which was projected continuously at the Whitney’s “Fragments of a Faith Forgotten,” is Smith’s most obviously structured film. The screen is divided into quarters. The images, which sometimes mirror each other, mix New York street scenes with country landscapes, a topless dancer, Smith’s Chelsea Hotel friends, occult gesticulations, and animated objects that include Thai sticks, licorice candies, and torn dollar bills. Predicated on a hypnotic use of symmetry and repetition, it is essentially an object of contemplation, an altarpiece. As such it holds its own as the central element in the exhibition—drawing energy, if not necessarily meaning, from the drawn zodiacs, string figures, paper airplanes, and stereo greeting cards that surround it.

As its title suggests, there’s a reliquary aspect to “Fragments of a Faith Forgotten.” The show is filled with traces of nonexistent works and stand-ins for works, like the Anthology, that don’t lend themselves to exhibition. The facsimile ethnographic slides are artifacts of artifacts. Some of the half-dozen film installations—like the sensational remnants of the Oz project—speak for themselves. But even these are also, like the drawings and animation slides, clues to what once was or might have been.

Smith explained that his films had a basis in “the interlocking beats of the respiration, the heart and the EEG Alpha component.” The same might be said of his jazz paintings. Now existing only as slides made by Jordan Belson, these were intended to be seen while listening to specific records, Dizzy Gillespie’s “Manteca” and Charlie Parker’s “Koko.” In a sense, they are static movies. They were painted between 1948 and 1951, during the ascendence of Abstract Expressionism, yet save for a tenuous connection to Kandinsky, their multiple frames, squiggly lines, dense tessellations, and shallow illusion of depth seem outside art history.

Despite this, and although The Anthology of American Folk Music and Heaven and Earth Magic are crank art masterpieces, Smith was in no way an outsider artist. Rather, he was outside the art world, at least as it has come to be recognized. Like the filmmaker–performance artist Jack Smith, Harry seems closer to the eccentric personalities of fin-de-siècle Paris, Alfred Jarry and Raymond Roussel, than to any notion of professional artist. There is nothing resembling a career. It would never have occurred to him to copyright any of his inventions. Smith had a flurry of public film screenings in San Francisco around 1950, then not again until the mid-1960s. Although he thought of himself primarily as a painter, there is no record of his paintings’ being exhibited, let alone purchased.

His tantrums rival the more purposeful acts of the 1960s movement known as Destruction Art. When denied a request for money or otherwise thwarted, Smith ripped up his drawings or trashed his rare books. He once unspooled a 16mm film on which he had labored for years down the middle of Broadway. Most famously, in 1965 he hurled the special projector he created for Heaven and Earth Magic out the fourth-story window of the Film-Makers’ Coop. At once creator and destroyer of his own personal cosmos, Smith was inseparable from his work. As noted by Susan Sontag in her 1966 essay “Film and Theatre,” he made “each projection an unrepeatable performance.”

He routinely—but not always—created difficulties for his audiences, insulting them, insisting that his films could be appreciated only when spectators were drunk or stoned. Perhaps this is why the Whitney provided a spacious collection of futons on which museum patrons might recline to dig Mahagonny. Hadn’t Smith told his exegete P. Adams Sitney, in the course of an uproarious, chaotic interview broadcast over WNYC in 1977, that “the best response to the film is if the audience goes to sleep”? That interview resulted in the cancellation of Sitney’s program, although he did, some years later, publish the transcript. Impossibly erudite, tossing off references to Claude Lévi-Strauss, Noam Chomsky, the Liverpool Codex, and the reggae movie The Harder They Come, Smith also regularly careens into outlandish territory (predicting, for example, an impending eruption of the Matterhorn). This wildly free-associative spritz could be taken for a Bowery bar rant or an elaborate put-on. While both are possible, the interview serves to illuminate Smith’s mental processes. So does “Fragments of a Faith Forgotten.” There are unexpected symmetries and correspondences everywhere.

From early youth, Smith was a student of cultures, whether Kiowa peyote rituals or kids’ paper airplanes. His collections as well as his identification with alchemy reflect an interest in discovering affinities, underlying structures, and formulae. In his final chapter, Szwed quotes the musicologist Peter Goldsmith, who, having interviewed Smith for Making People’s Music, his 1998 biography of Moses Asch, noted that “Harry’s mind works much too fast for his mouth to handle the output.” Writing to the Baroness Rebay in 1950, Smith described his second animation as “an investigation of the rhythmic organization of man’s mind” and a recording of the “daily changes” in his brain. Trapped in the prison of his own sensibility, he perhaps sought above all to organize that feverish mind and in so doing reorganize the world.

This Issue

March 21, 2024

Who Should Regulate Online Speech?

Laugh Riot

Small Island

-

*

See Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music: America Changed Through Music, edited by Ross Hair and Thomas Ruys Smith (Routledge, 2016). ↩