How did countercultures commune before the Internet? One quaint and underappreciated precursor to the information highway was the underground press that proliferated during the late 1960s. The medium was never more the message. Sprouting in cities and college towns across America, these rambunctious weekly or biweekly tabloids flourished for a half dozen years, a form of what, referring to the spontaneous development of jazz, Ishmael Reed—a cofounder of a quintessential such paper, the Lower Manhattan–based East Village Other, a.k.a. EVO—called “Jes Grew.” Thanks in part to the Underground Press Syndicate (UPS), a national network whose members were allowed to reprint one another’s work, these self-identified rags spread like kudzu—to take the name of a triweekly published in Jackson, Mississippi.

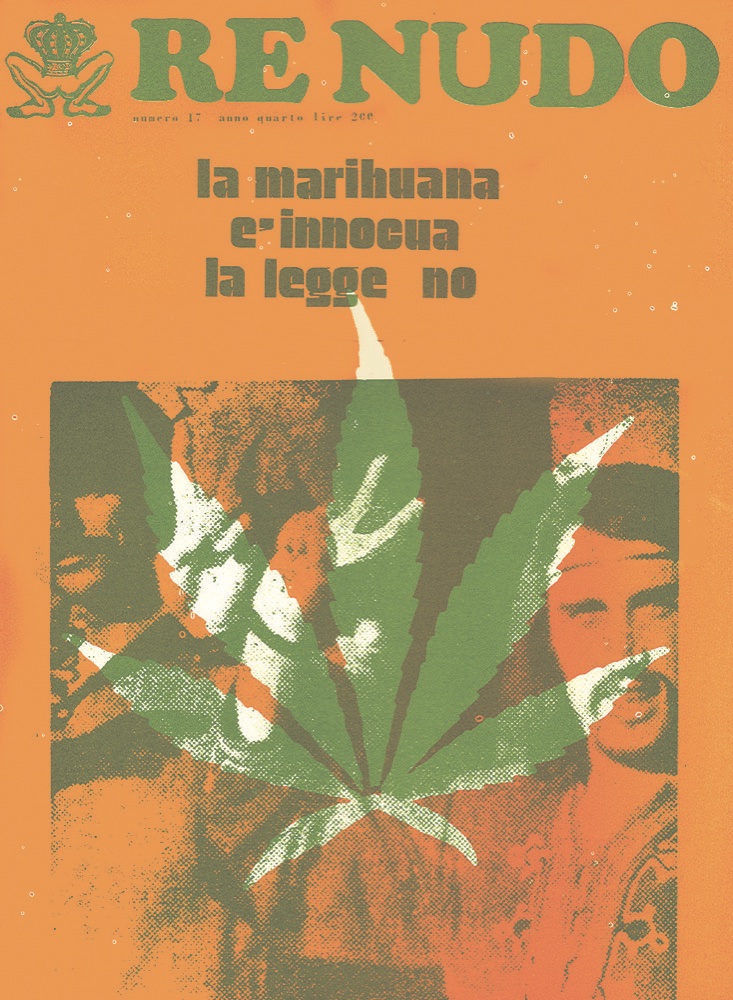

The vegetative metaphor was inevitable. According to Heads Together: Weed and the Underground Press Syndicate, 1965–1973, an artfully designed scrapbook curated by David Jacob Kramer, two entities propagated the underground. One was the UPS, which included five papers at its founding in 1966 and grew nearly fiftyfold over the next five years. The other was the popularity of marijuana. The UPS dissolved by degrees in the mid-1970s, whereas weed, fulfilling a fond dream of the underground press, has solidified its legality.

Thus Heads Together is something of a wonder tale. Kramer, an Australian writer and publisher, was born in 1980, well after virtually all of the major underground papers—the Los Angeles Free Press, Berkeley Barb, East Village Other, Austin Rag, Chicago Seed, and Rat Subterranean News among them—folded. (The great exception, Detroit’s Fifth Estate, once the province of the jazz poet and pot martyr John Sinclair, continues to this day as a militantly eco-anarchist triquarterly.) Kramer’s view of these chaotic publications is selective, subsuming individual writers and artists, as well as numerous issues, under the five-leaf symbol of the cannabis plant.

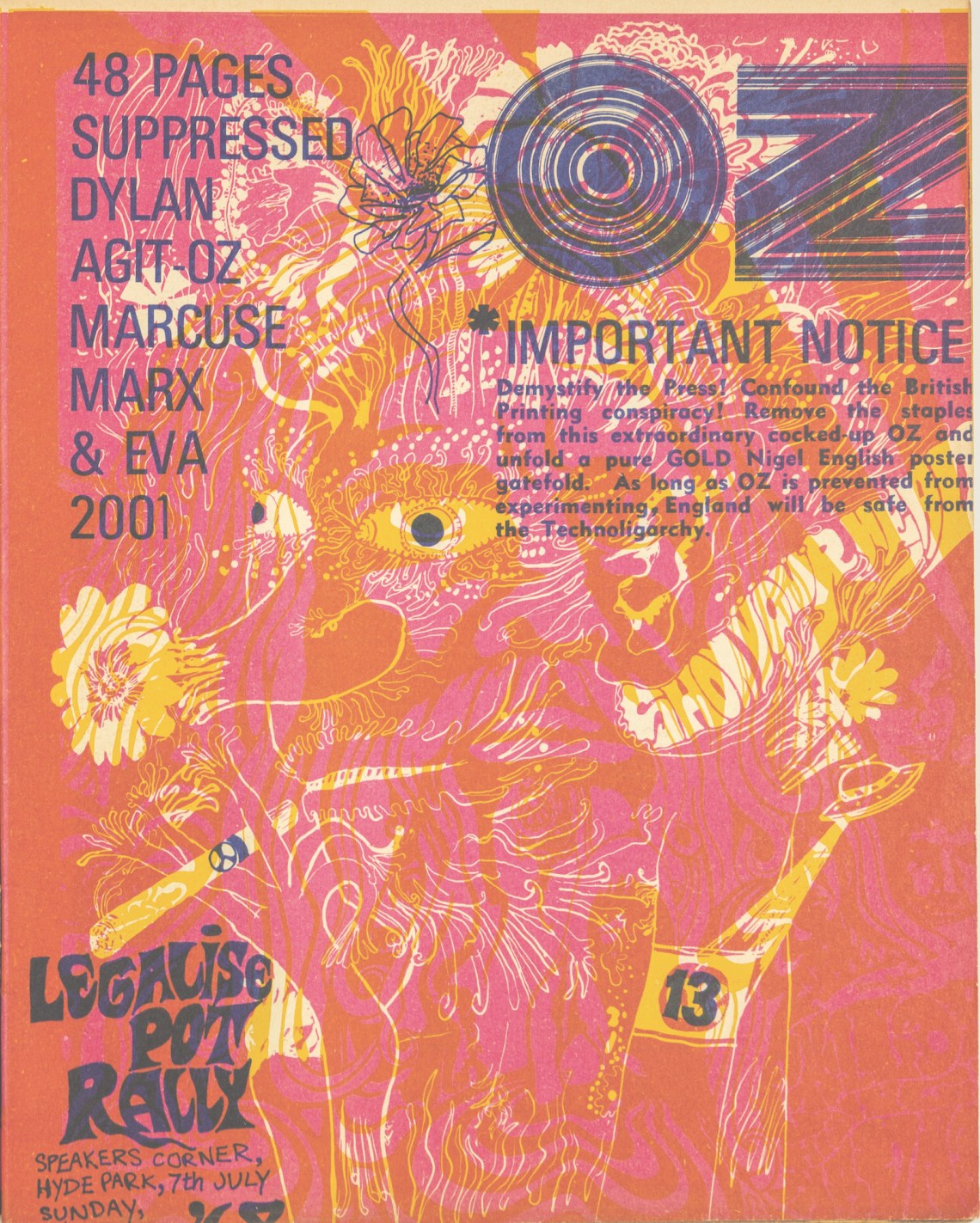

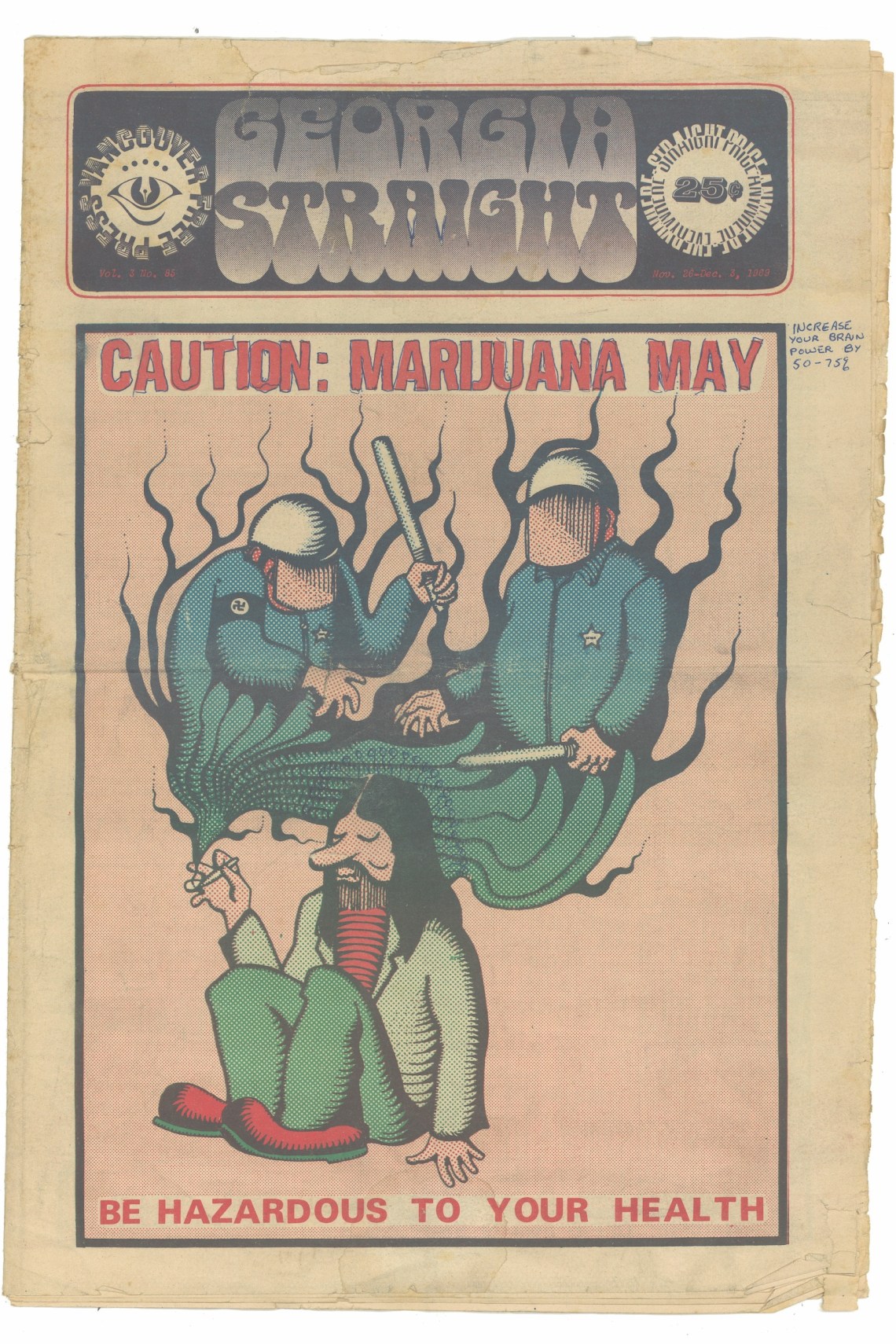

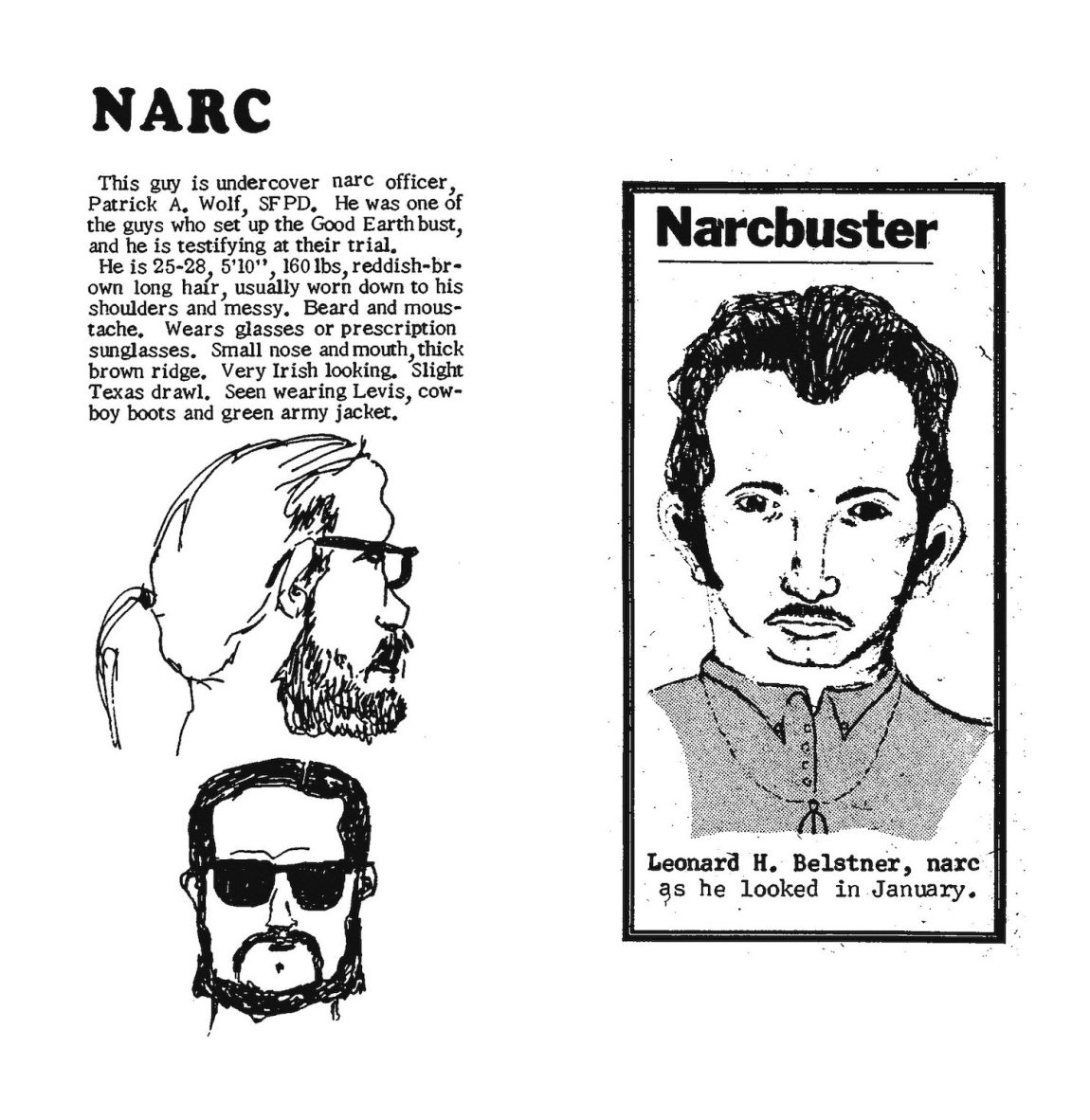

The mainstream media of the 1960s was unsympathetic to Black Power, youth culture, and the peace movement, as well as to smoking pot. The underground press advanced an alternative worldview. It was a public listserv in which a host of committed proto-bloggers reported or ranted on demonstrations and be-ins, exposed police spies, interviewed disaffected soldiers, cheered on teenage militants, publicized anarchist street gangs, pondered free-love communes, promoted exotic gurus, marveled at naked performance artists, profiled rock musicians, and discovered midnight movies. In lieu of Google it offered tips on treating VD, coping with bad trips, and dealing with the “pigs,” while providing a smorgasbord of outré comic strips, soft-core porn, Black Panther communiqués, and messages from the likes of Herbert Marcuse and William Burroughs. In 1968 New York City had three underground papers—EVO, Rat Subterranean News, and the New York Free Press—as well as the Beat era alternative weekly Village Voice, and a monthly “of, by, and for liberated high school students.”

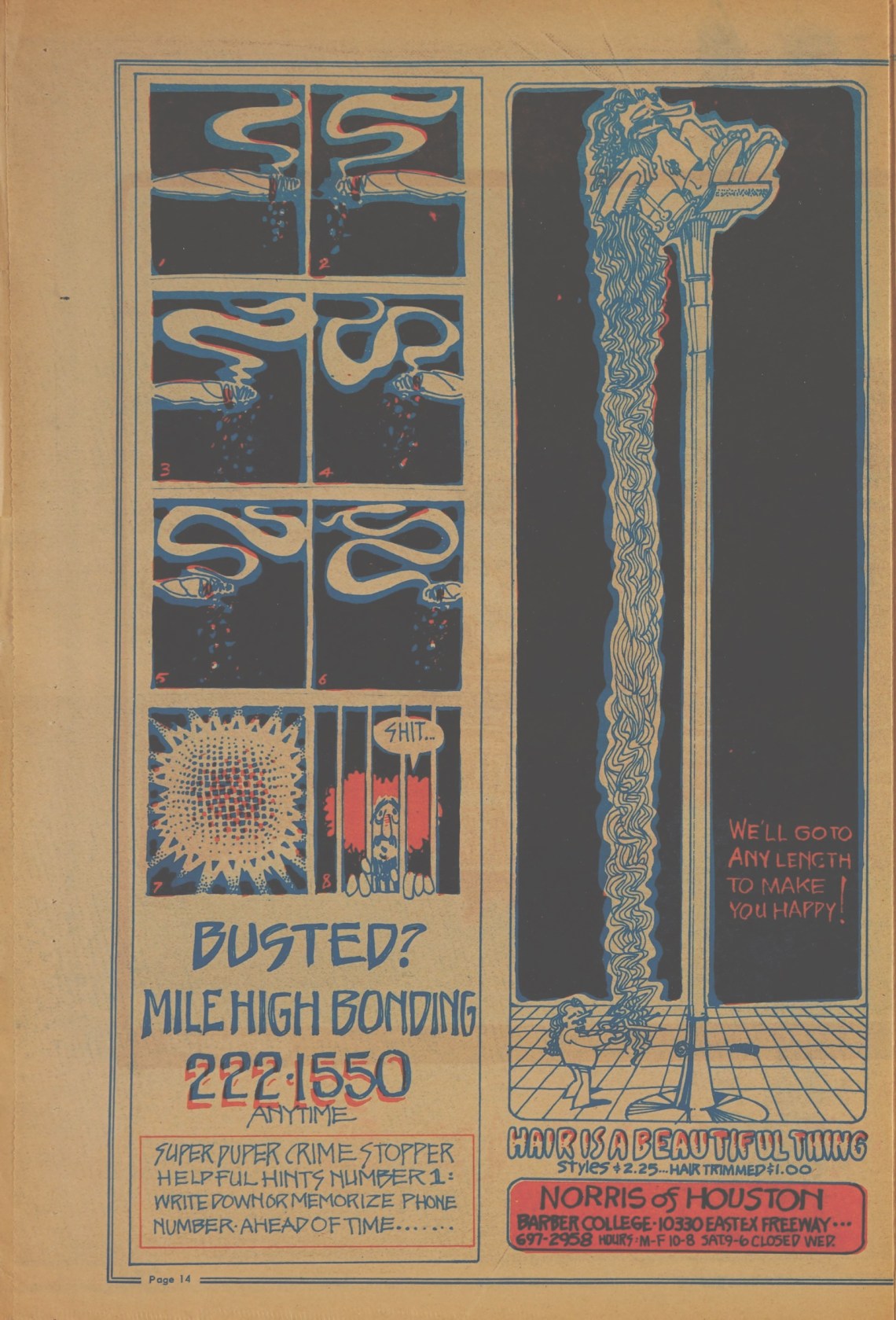

To the degree that the underground press was anti-authoritarian—by 1969 papers were glorifying guns and publishing recipes for Molotov cocktails in addition to advocating for drugs—it was subject to both official and unofficial harassment. Papers had their offices trashed and sometimes bombed.1 Like the Internet, the underground press encouraged conspiratorial thinking and engaged in its own form of harassment. The papers, it cannot be denied, could be inordinately male supremacist. At best a nerdy locker-room atmosphere prevailed. At worst, the rags were smugly objectifying in their drooling representation of “chicks” and “old ladies.” (Nor was homophobia unknown.)

Payment was minimal or nonexistent, although the underground press did provide entry-level opportunities for would-be writers. (I was one, first published in EVO’s short-lived successor, the New York Ace.) Underground papers needed movie and music reviews to support the ads that, along with salacious classifieds, were their economic support system. The week after Richard Nixon’s first election, Columbia-CBS Records bought a full-page spread in college and underground papers across the country depicting seven dudes hanging out in a dorm room–cum–jail cell, absurdly captioned BUT THE MAN CAN’T BUST OUR MUSIC. Soon after, the FBI discouraged big record labels from such patronage.

Art design was erratic, although the splendiferously trippy, Art Nouveau–meets–Tibetan Buddhist San Francisco Oracle (1966–68) was a masterpiece of hippie modernism. Political cartoons could be savage and artless enough to shock George Grosz. But the print forms the counterculture truly pioneered were bawdy underground comix and less creative soft-core porn. In 1969—the same year EVO published eight issues of the short-lived all-comix Gothic Blimp Works, another masterpiece quite different from the Oracle—the New York underground press was outflanked and outsold by the new sex tabloids, most infamously Al Goldstein’s Screw. EVO put out a marginally less tasteful competitor, Kiss, while the New York Free Press became the “tony” New York Review of Sex. Crude sexual display in ads as well as editorial content contributed to a staff revolt at Rat, the most political of New York’s underground papers, where a feminist collective purged the men and took over the publication.

Advertisement

*

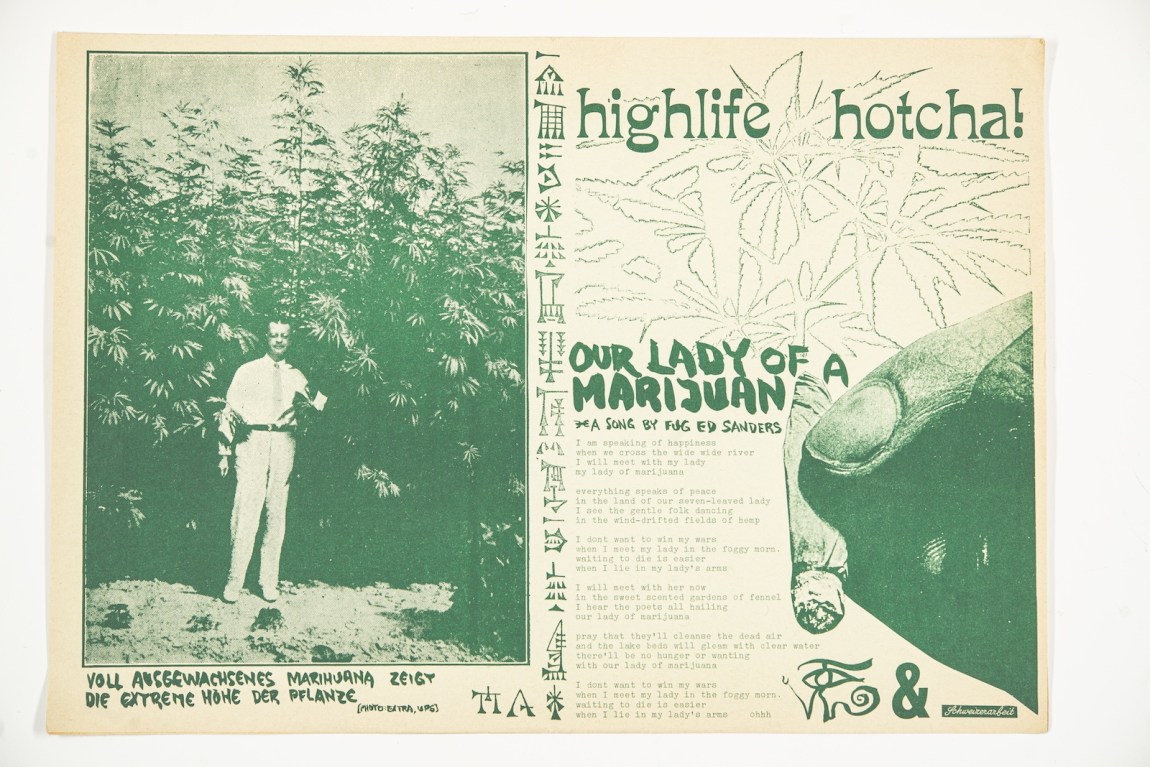

Kramer’s focus on the importance of weed to the underground press may seem reductive, but the relationship was real. Rags were not infrequently bankrolled by dealers. Thomas Forçade, who built up and ran the UPS and later founded the glossy magazine High Times, was a major importer of Mexican and Colombian marijuana. EVO’s greatest home-grown cartoonist, Kim Deitch, recalled being paid with pot. Politicos saw an opening. The Weather Underground’s first communiqué, issued in 1970 and disseminated throughout the counterculture by the UPS, attempted to make common cause. “Dope is one of our weapons,” the revolutionaries declared. “Guns and grass are united in the youth underground.”

The grass connection outlived the revolution. No less than the violent New Left, the underground press was a transitory phenomenon. By the mid-1970s counterculture rags had mutated into or been replaced by less outrageous alternative weeklies, which have themselves since been rendered largely obsolete—ghost towns bypassed by the information superhighway. (And yet industry observers noticed the ad bounce enjoyed by alt-weeklies in Colorado and Washington after those states legalized recreational cannabis in 2012.) Heads Together is pegged to the nationwide trend toward what we might call “dispensarization”—the transition of the pot economy from dealers to state-licensed vendors—yet somewhat ambivalent regarding the loss of marijuana’s outlaw status. Its final pages are an irate collection of tweets on the embourgeoisement of dispensary cannabis and the exploitative nature of Big Weed.

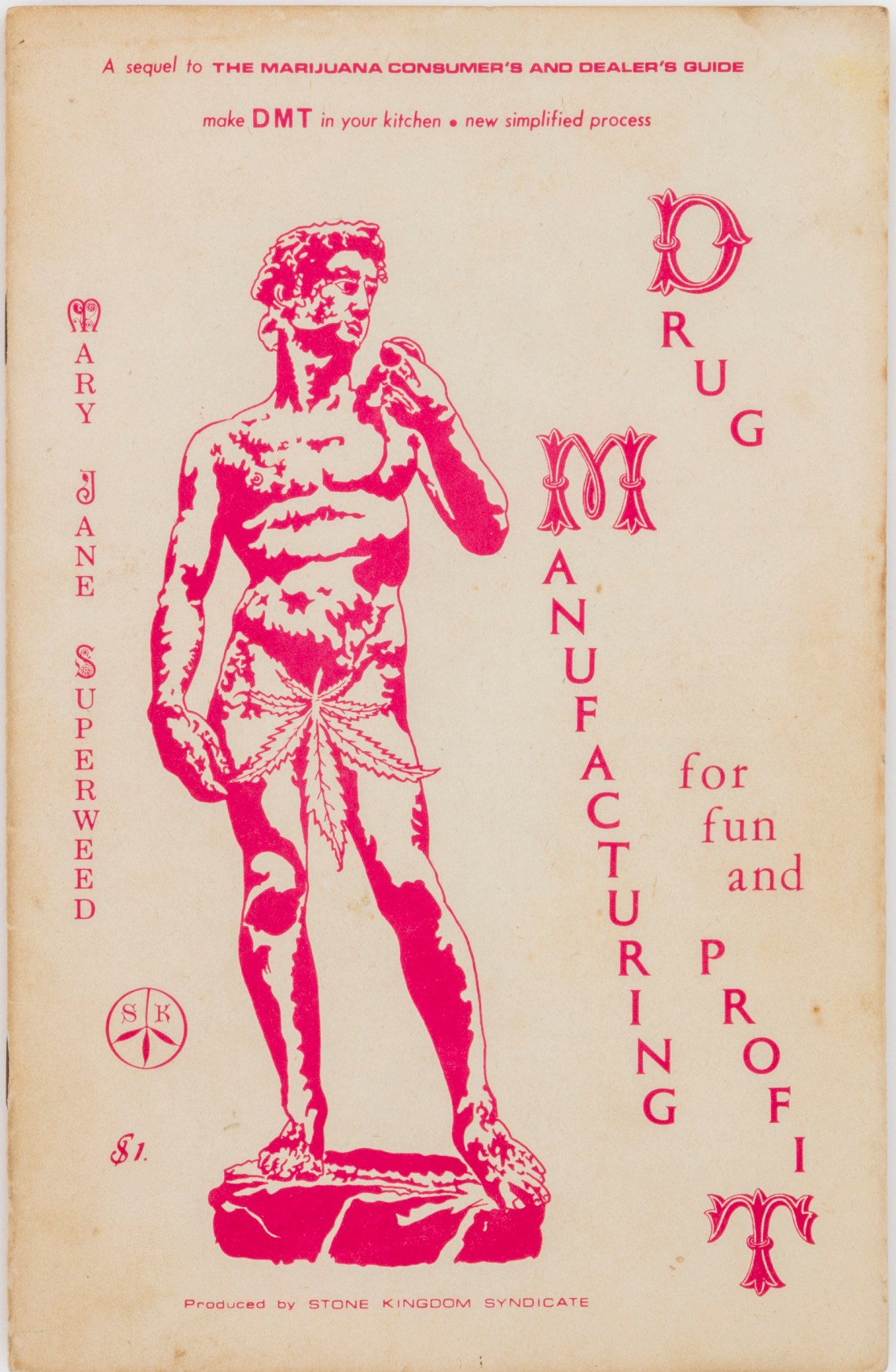

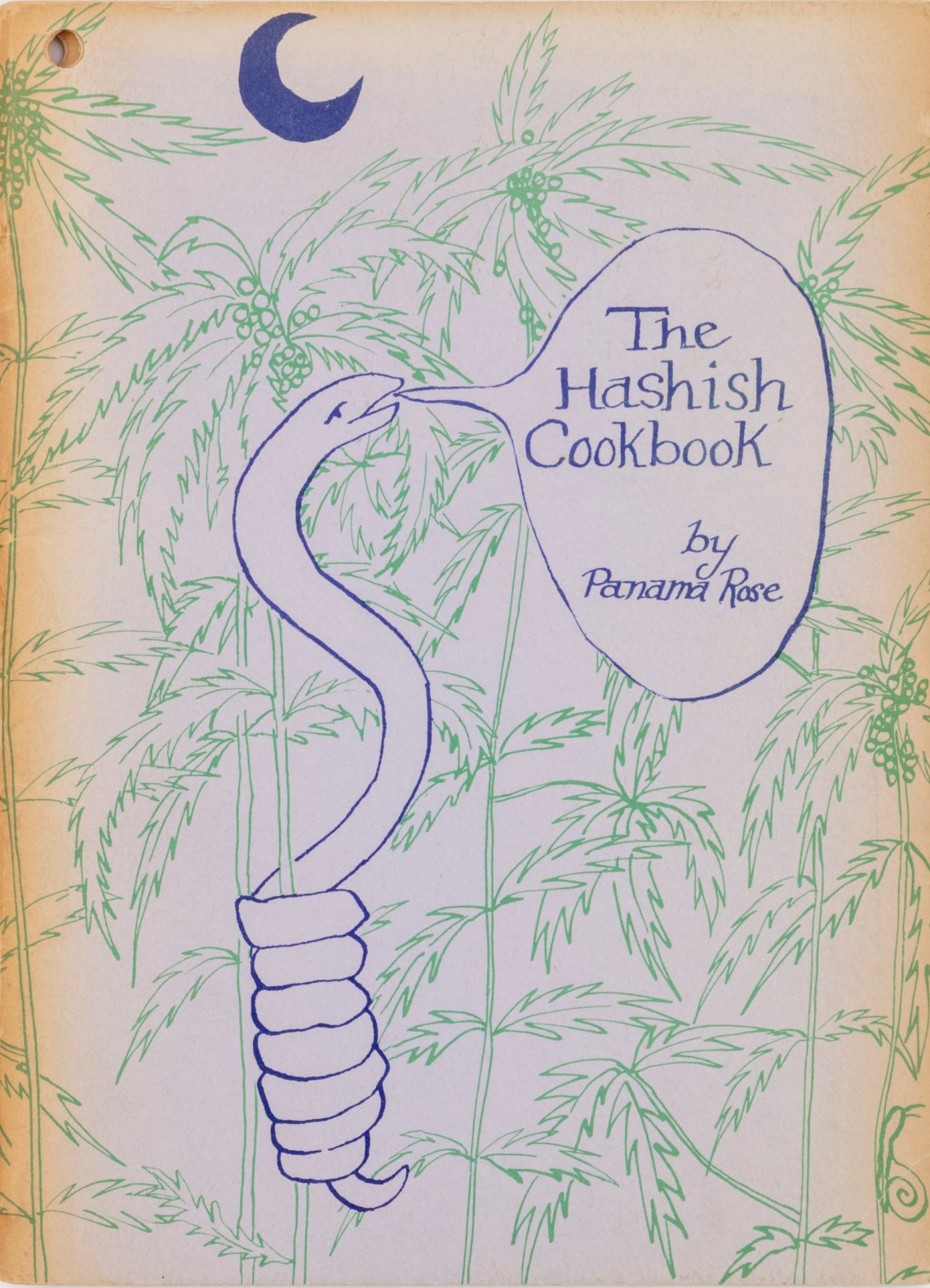

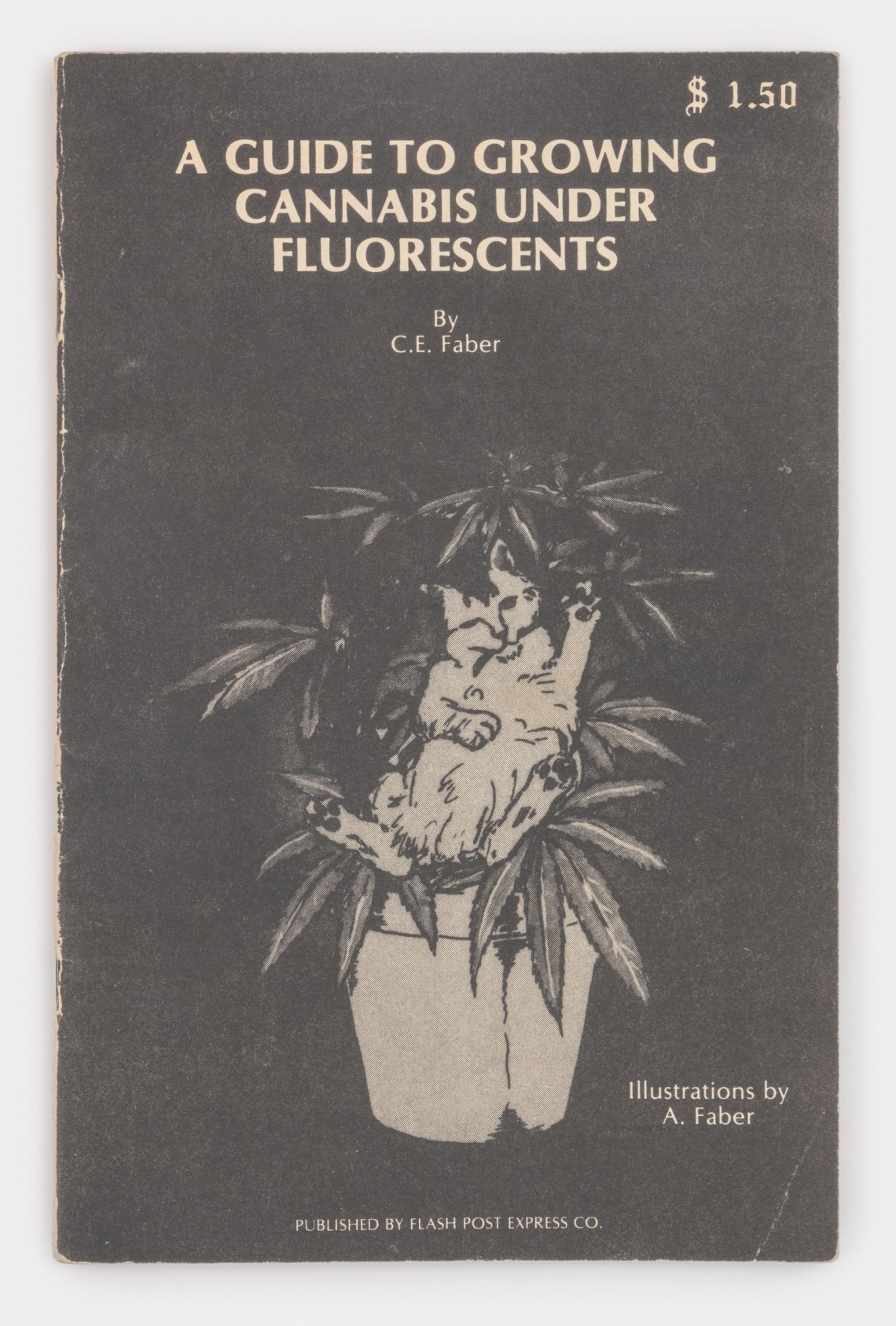

While no one’s idea of a Rizzoli-type coffee-table tome, Heads Together would not look out of place on the sort of scavenged orange crate that once furnished crash pads and student hovels—it’s a spiffy version of a late 1960s rag. The trim is compact. The page count (around 560) is generous. The binding is forgiving. Most important, the Munken Print Cream paper is friendly to newsprint. The original raggedy images are dynamically cropped or enlarged, sometimes bleached or tinted. The layout is considered, albeit more immersive than informative—though Heads Together does acknowledge that the underground press was an invaluable source of information, not least on marijuana cultivation. It devotes sixty-six pages to illustrated grower’s guides.

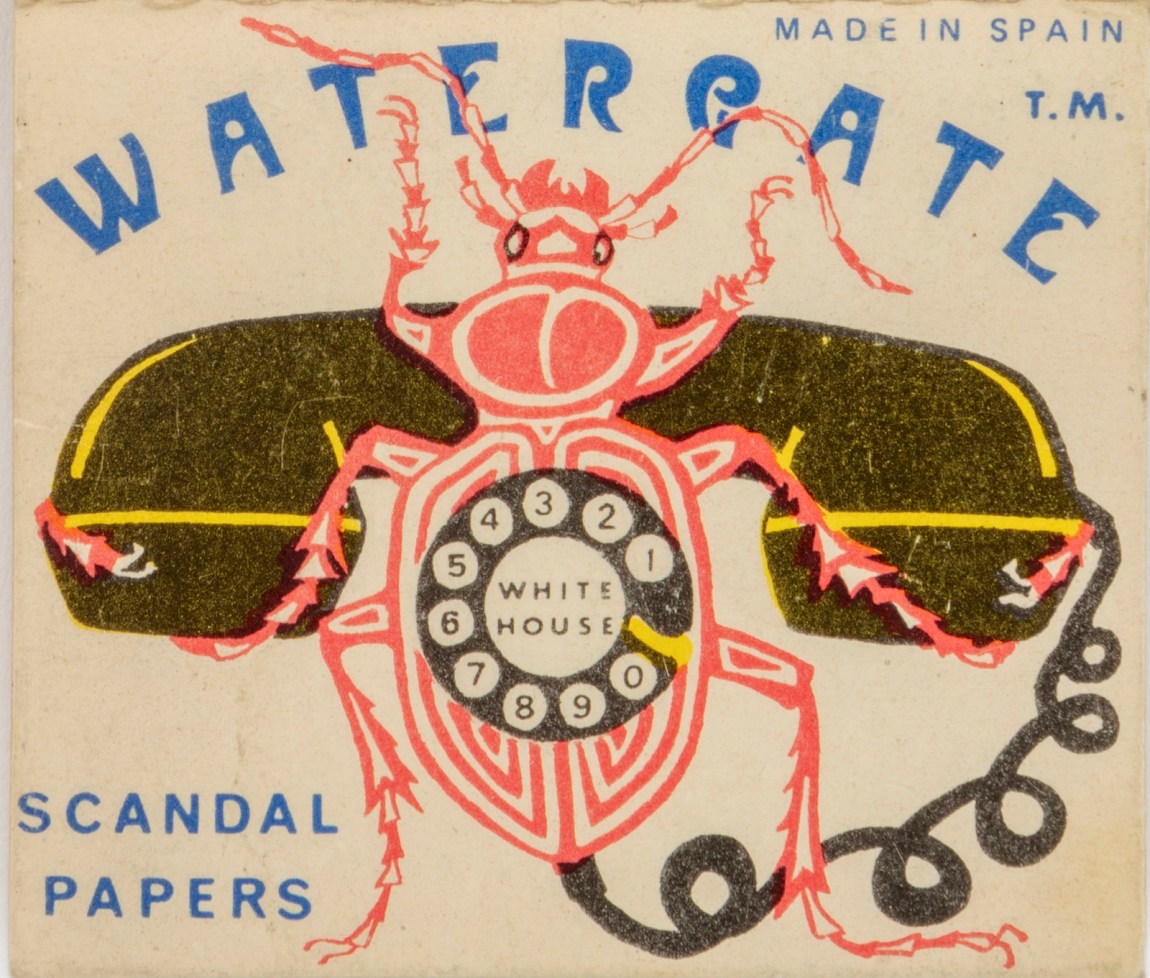

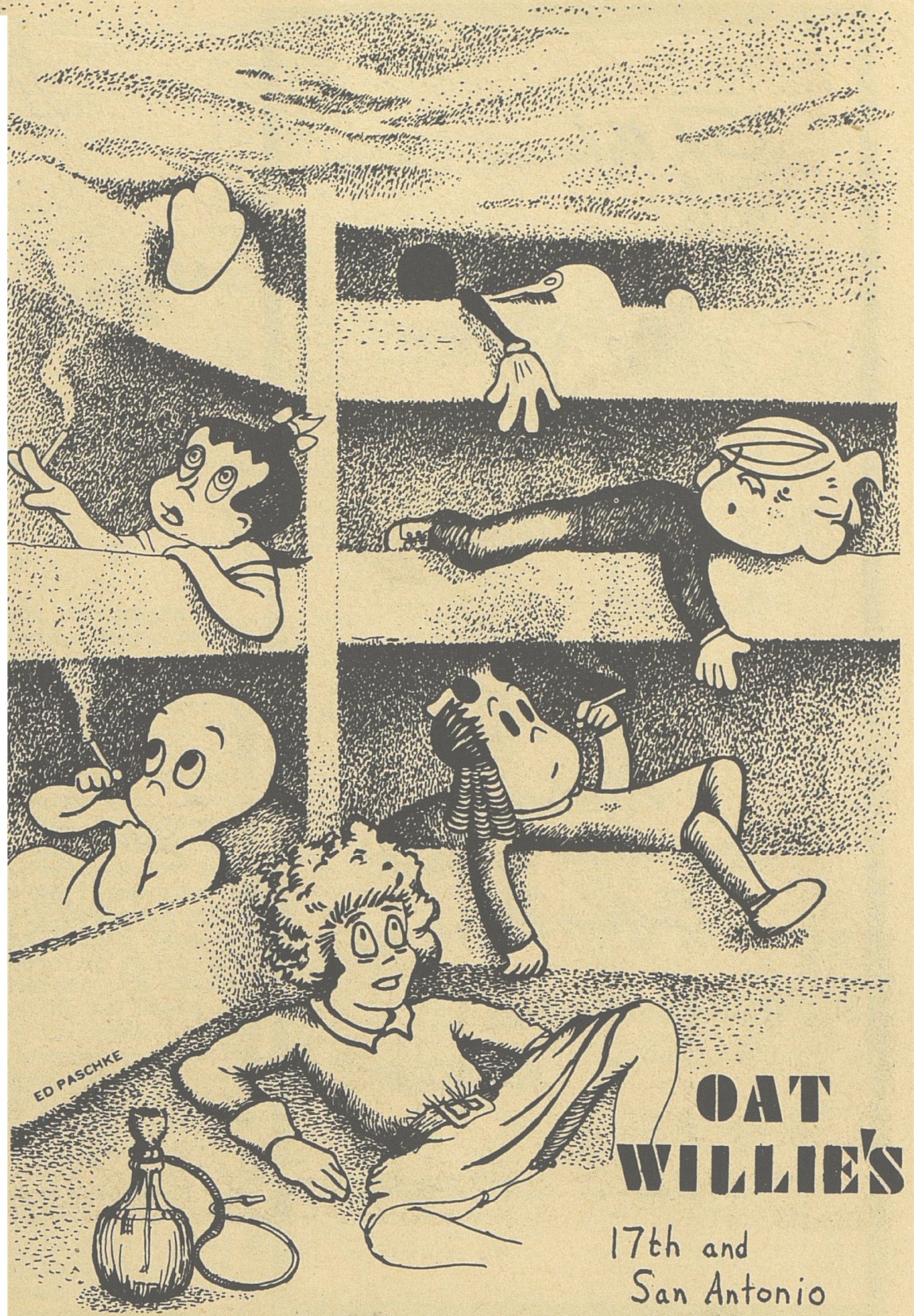

As much as anything, the book reinvents underground newspapers as repositories of folk art. The spot illustrations of marijuana plants might be prison tattoos; the public-service cartoons of actual, police-informing narcs could have been drawn on a paper napkin. The five-leaf permutations are many. The most glorious color section is the eighty-page gallery of decorative rolling papers from Spain, the US, and France. Ephemera is lovingly preserved.

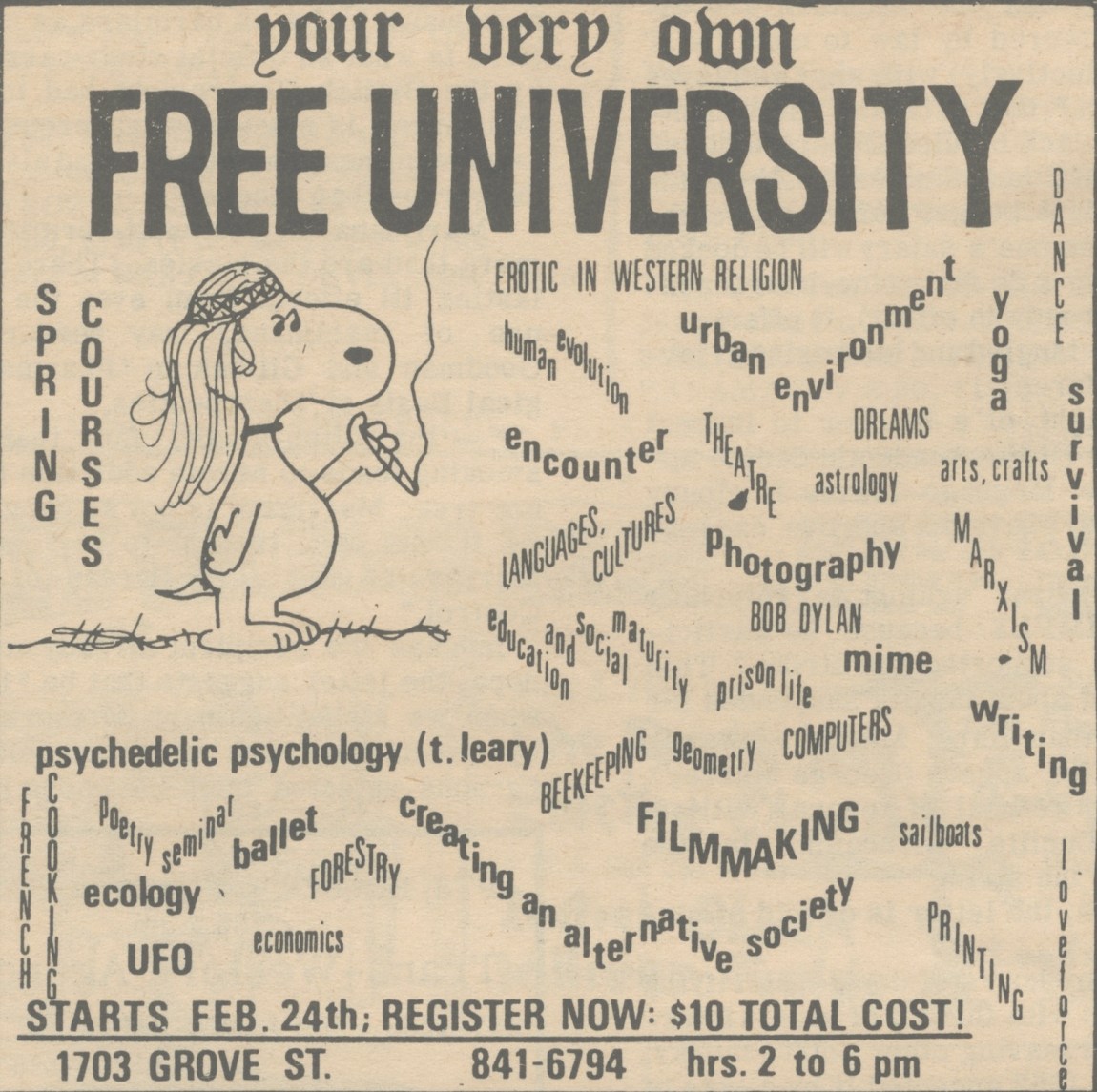

Heads Together represents the counterculture but repackages it. Political insanity and prevailing sexism are considerably toned down. There are no Slum Goddess pin-ups or Up Against the Wall Motherfucker exhortations, no “ironic” racist or pedophilic comix. Photos of four-year-old kids posed puffing on joints—one from the cover of the Berkeley Barb, the other from that of San Francisco Express Times—might be discomfiting, but far more attention is given to the press’s detournement of official culture: Snoopy with hippie headband holding a doobie; Donald Duck getting high with Uncle Scrooge; Little Orphan Annie, Little Lulu, Dennis the Menace, and Casper the Friendly Ghost zonked in an opium den; Elmer Fudd taking up the gun to free martyr John Sinclair, jailed for laying two joints on an undercover agent.

“I wanna get high but I never know why.” So sang David Peel, the sometime Catullus of Tompkins Square Park, over fifty years ago on his first LP, Have a Marijuana. It’s not a question that Heads Together attempts to answer—but then, to be fair, it’s not a question the book feels obliged to ask.

Advertisement