“I draw a lot of weird doodles on scraps of paper,” says the Canadian cartoonist Jesse Jacobs—true of most cartoonists, no doubt. But few cartoonists’ work is as suffused with the spirit of the doodle as Jacobs’s. The familiar forms are there on almost every page: a profusion of cubes and spheres, wiggly organic textures, vast fields of invented vegetation. They are more elegantly drawn than your average doodles, of course, cleaned-up and colored and carefully arranged, but the doodler’s mix of repetition and improvisation is unmistakable in each of his books, from the mountain landscapes of Even the Giants (2010) to the interstellar geometries of By This Shall You Know Him (2012) to the proliferating jungles of his newest, Safari Honeymoon. As a result, even at their wildest or most grotesque—a man with a toothy parasite in place of a tongue, for instance, in Safari, or a god-like being consisting of a non-Euclidean latticework filled with tentacles, in By This—his drawings are always warm and inviting, with their not quite perfect edges and soothing sense of a hand in motion.

But what is most impressive about Jacobs is not the attraction and inventiveness of his artwork, but his ability to shape those doodler’s inspirations into a story—a satisfying, affecting, often startlingly strange whole. By This Shall You Know Him is a riot of complex geometrical assemblages, swirls of spheres and tendrils, and lumpy organic surfaces. But it is also a sly retelling of Genesis, with a memorably rude, intimate version of the cosmos: Earth, the universe, humanity, and sin itself are all the result of rivalries within a sort of metaphysical writers’ workshop for creative deities; one omnipotent being creates the Earth and fills it with fluffy animals, another, jealous of their teacher’s approval, peoples it with lumpy proto-humans, and teaches them to kill.

Safari Honeymoon, Jacobs’s new book, is narrower in scope, but in many ways even stranger and more impressive. The title is literal: it tells the story of two newlyweds on a luxury getaway to a bizarre, unnamed wilderness, complete with hunting, luxury meals, and a hardbitten guide-cum-chef. Though Jacobs’s dialogue has a deadpan wit, this trio are never much more than stock types—the husband a condescending bigshot (“I am entitled to a clean wine glass on my honeymoon!”), the wife friendly and inquisitive, the guide stoical and competent. But that is beside the point. These characters are just an excuse for Jacobs to run through a fantastical set of variations on the theme of alien nature, and man’s encounters with it.

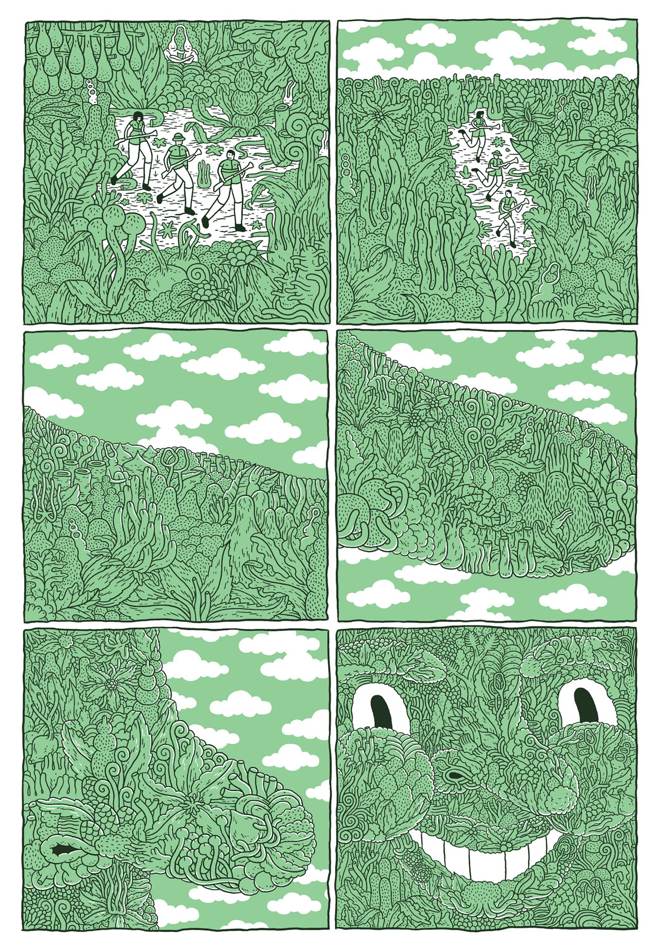

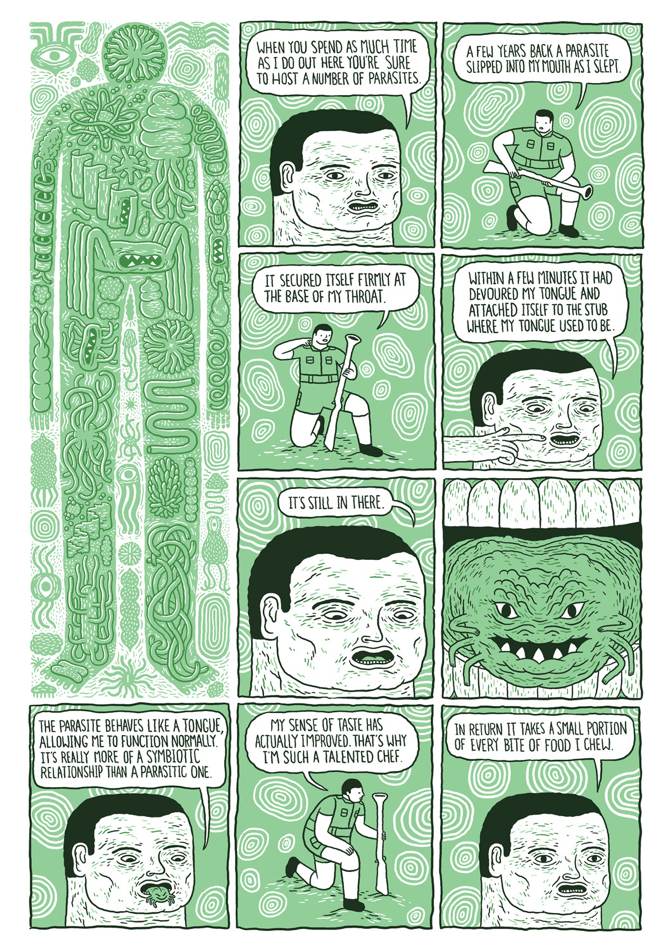

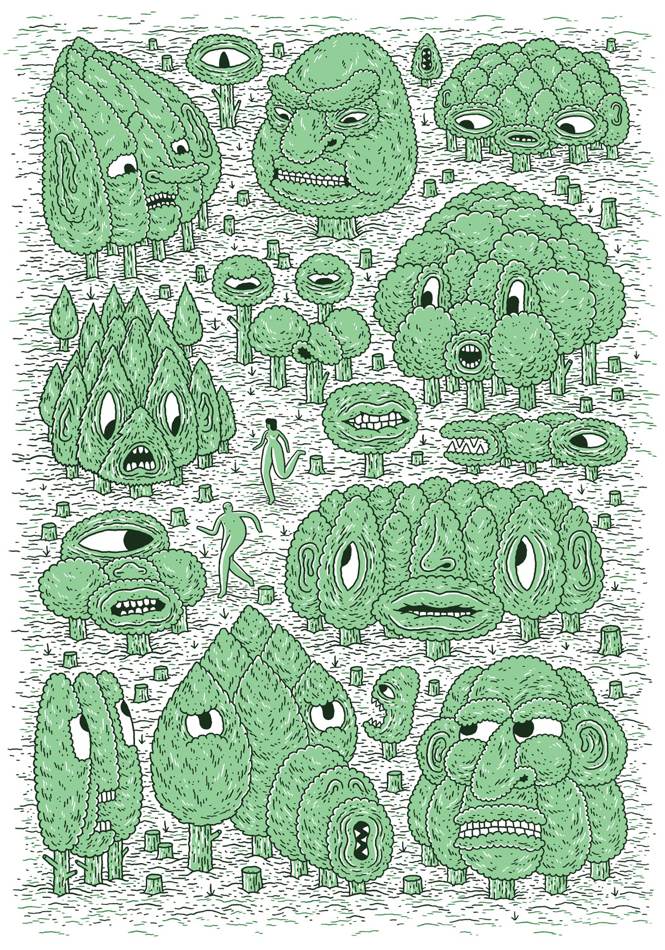

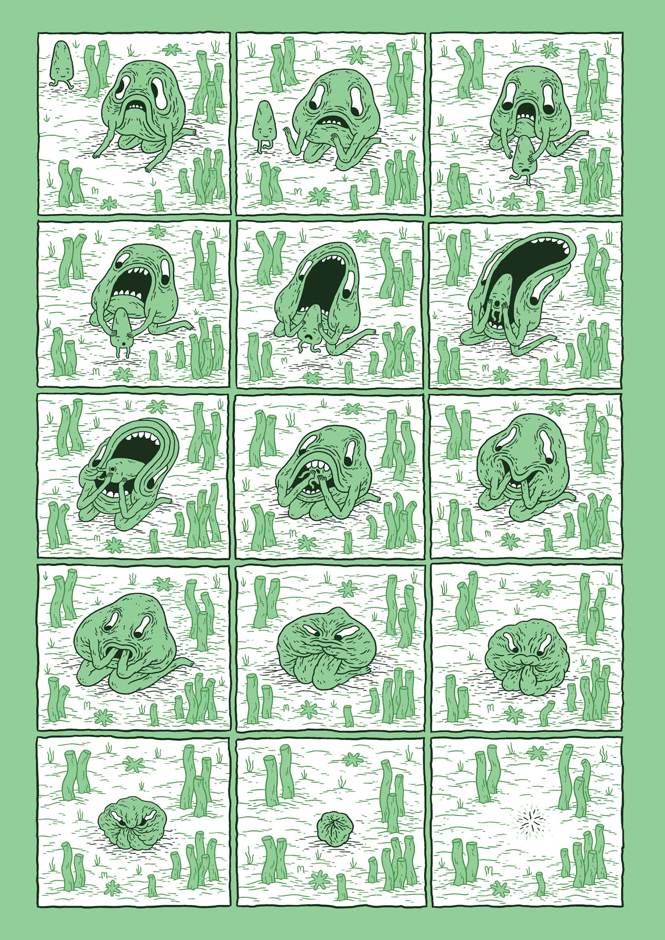

The three humans wander through forest and scrub, through “pockets of temporal distortion” and a sort of lake so subtly underwater the newlyweds only notice they are submerged when the gun won’t fire. They hunt (“That was rather exhilarating!” says the husband, knocked over by his own recoil), and are hunted in turn—menaced by a mobile, anthropomorphic forest grove, swallowed by a furry, almond-shaped monster with a very yonic mouth, chewed on by a four-legged, bodiless cyclops. Parasites threaten their orifices—the guide pulls a hissing worm out of the husband’s ear, but is later infected himself—and ethereal, telepathic “forest apes” watch them from afar. At one point Jacobs suddenly pulls back to show that the whole forest is actually the face of a maniacally grinning giant, a “revelation” that is never returned to.

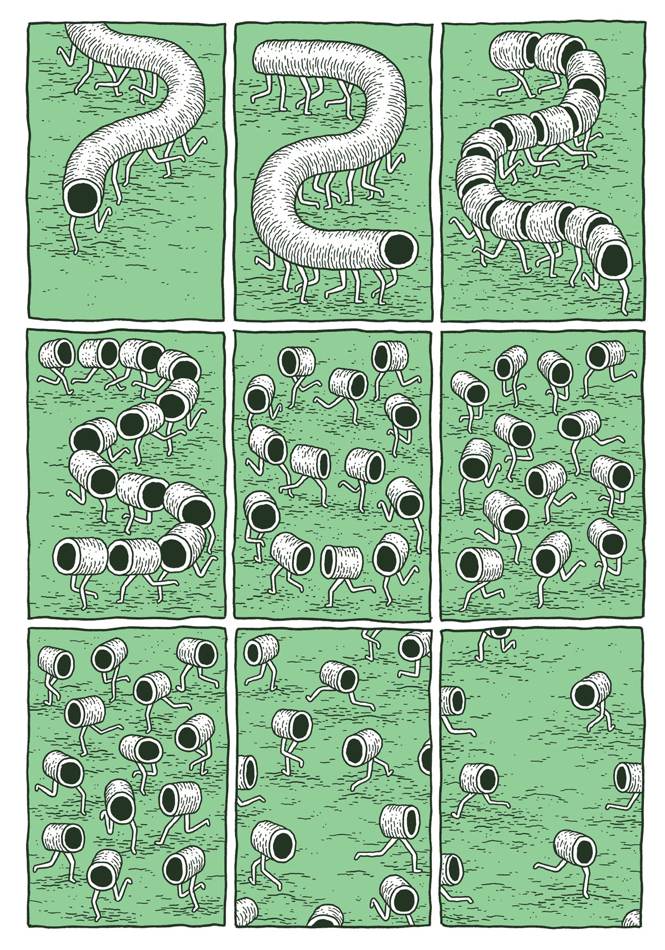

The story is told with a syncopated, off-kilter rhythm. Pages featuring the progress of the main characters are interrupted by wordless drawings of fauna, and of their gourmet meals, by gnomic advice from the humanoid trees (“Predetermined patterns of thinking are inadequate. Your thoughts are nothing more than meaningless clouds passing across an endlessly blue sky”), by explanatory interludes on the life-cycle of the parasites and the training process for guides. It is a structure that keeps the reader both amused and off-balance, and allows for a very unusual mix of tones. Comedy, horror, and wonder are intermingled throughout, and calamitous events are resolved with unsettling happiness. “Everything,” the narration informs us in the opening pages, “at some point is reduced to its most primitive state,” and by the end of the book Jacobs almost seems to be telling the story of Eden in reverse—or perhaps that’s just another joke.

Jesse Jacobs’s Safari Honeymoon is published by Koyama Press.