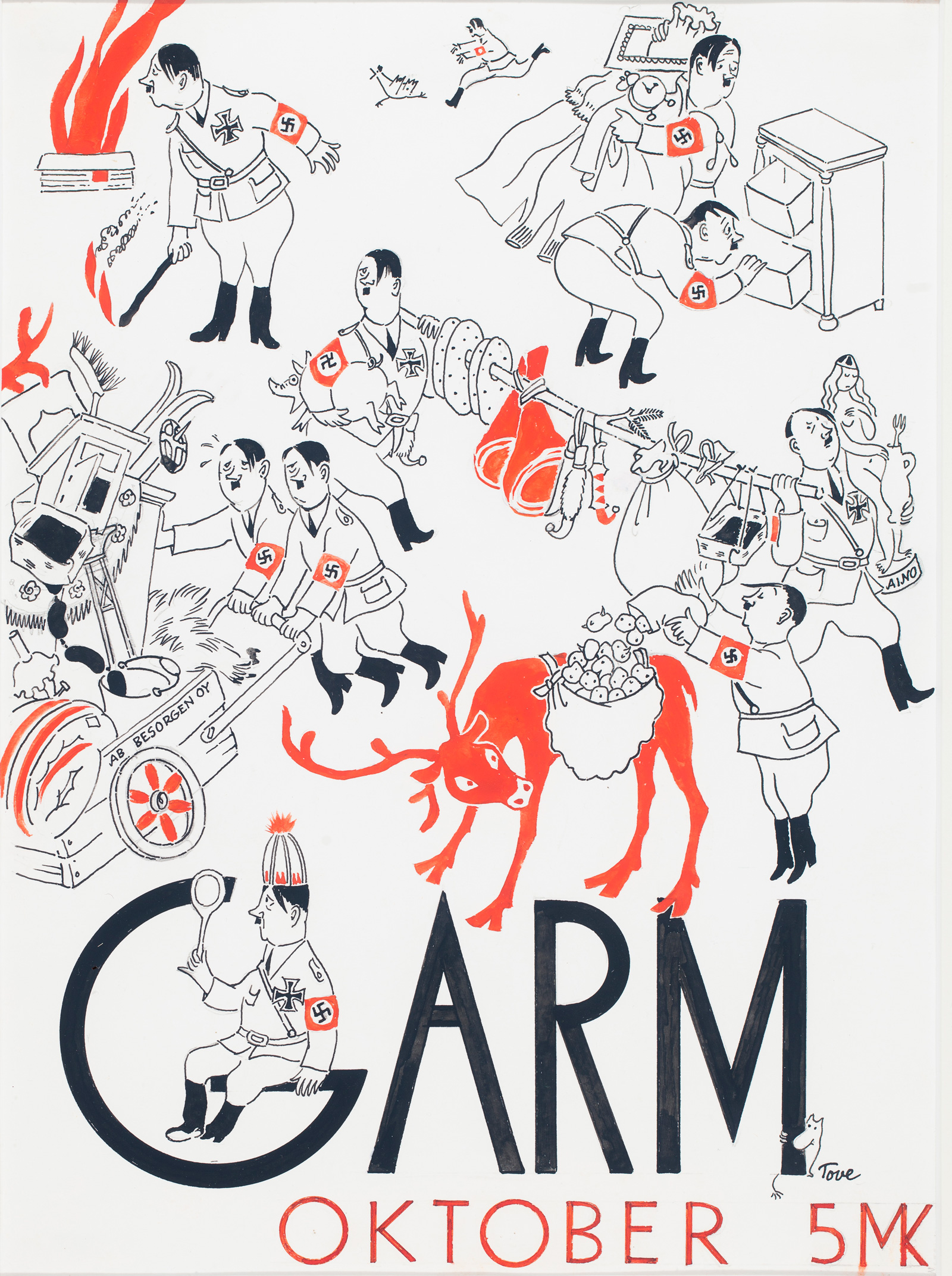

In October 1944, Tove Jansson drew a cover for Garm, a Finnish satirical magazine, showing a brigade of Adolf Hitlers as pudgy little thieves. In one corner of the page, they rifle through someone’s drawers, in another they shovel possessions onto the back of a cart, and at the top a lone Führer sets fire to a house. Caricatures like this were not unusual for Jansson, who had been belittling Stalin and Hitler in the magazine since the early days of the World War II. Newer, though, was the tiny pale figure with a long nose peeking out at the chaos from behind the magazine’s title. This was one of the earliest appearances of a Moomin.

This piece, which is shown in the first room of a new retrospective of Jansson’s work at the Dulwich Picture Gallery in London, represents a turning point in her career and life. Born in Finland, Jansson (1914–2001) contributed her first illustrations to Garm as a precocious fifteen-year-old, and alongside her magazine work she developed a successful career as a painter. Then, in 1945, she published The Moomins and the Great Flood, the first in a series of nine children’s books about a family of hippo-like creatures living in Moominvalley, a place of forests and rivers on the coast of Finland. The books, in which Jansson intersperses her stories with simple line drawings of the Moomins and their adventures, have been translated into forty-four languages and have sold over fifteen million copies, in addition to which Jansson drew a Moomin cartoon strip syndicated to 120 newspapers around the world. The popularity of the Moomins spawned an empire of television shows, films, and theme parks, as well as all manner of merchandise from plastic toys to crockery.

But over time, Jansson came to feel exhausted by the Moomins and that their success had obscured her other ambitions as an artist. In 1978, she satirized her situation in a short story titled “The Cartoonist” about a man called Stein contracted to produce a daily strip, Blubby, which has generated a Moomin-like universe of commercial paraphernalia—“Blubby curtains, Blubby jelly, Blubby clocks and Blubby socks, Blubby shirts and Blubby shorts.” “Tell me something,” another cartoonist asks Stein. “Are you one of those people who are prevented from doing Great Art because they draw comic strips?” Stein denies it, but that was precisely Jansson’s fear.

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in Jansson’s work beyond the Moomins. Much of this has focused on her novels for adults, which she began writing in the late 1960s and include short, crystalline works like The Summer Book (1972) and The True Deceiver (1982), which have been reissued in English since her death. Less attention has been paid to her range as a visual artist—something the Dulwich exhibition aims to rectify. The first room contains paintings made during the 1930s and 1940s, along with a case of her wartime political cartoons. The next room displays canvases from the 1960s and 1970s, by which time Jansson had given up the Moomin cartoon strip. These are followed by rooms dedicated to her illustrations for children’s classics like The Hobbit and Alice in Wonderland, for the Moomin books and, finally, her Moomin cartoons. The exhibition’s progression has two somewhat contradictory results. On the one hand, by opening with unfamiliar parts of Jansson’s oeuvre it emphasizes her breadth. On the other, it gets that out of the way before moving on to better-known material. Its momentum ends up flowing toward the Moomins rather than away from them.

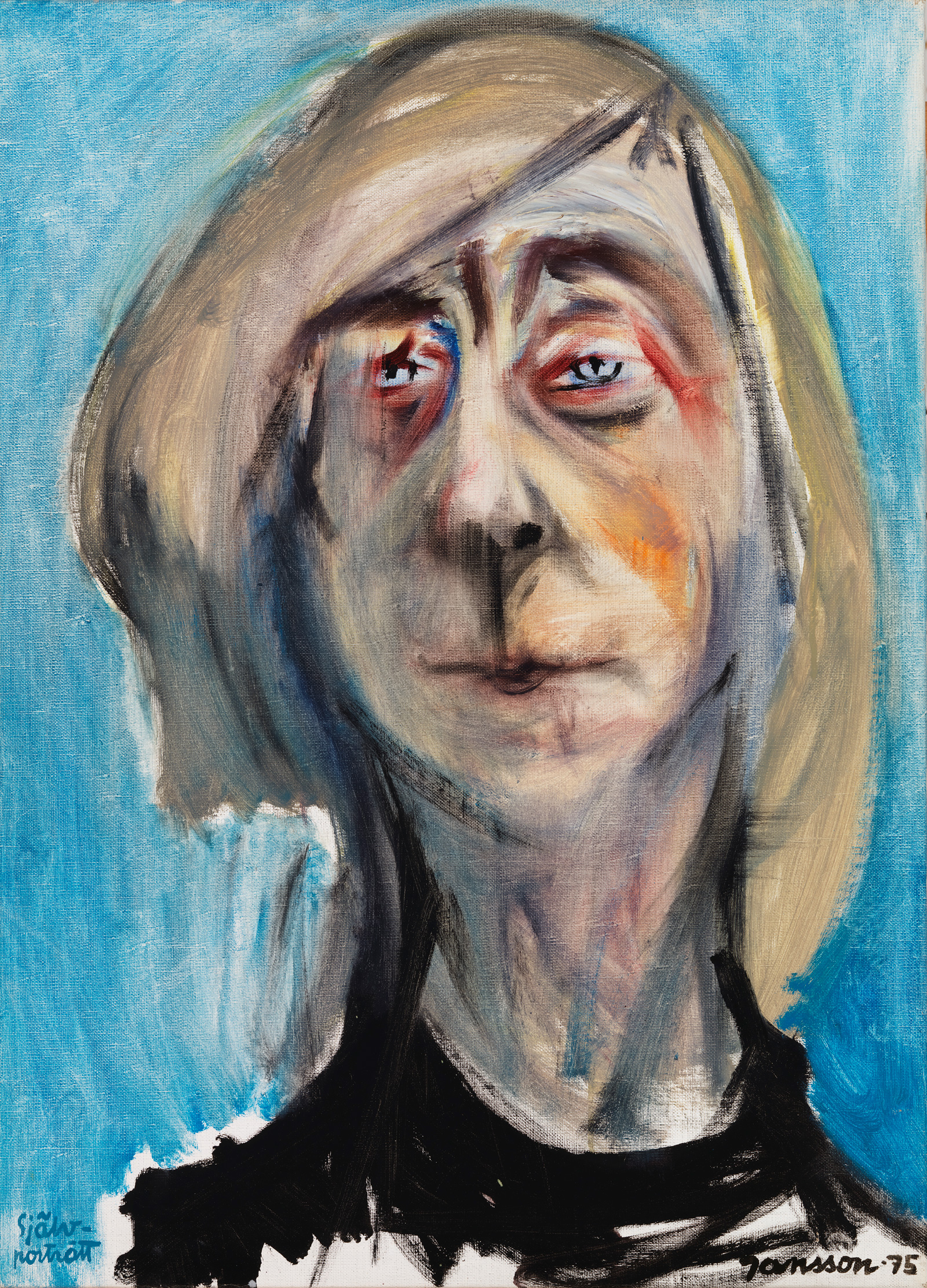

For anyone familiar with Jansson from the Moomins alone—with their spontaneous, scratchy, pen-and-ink sketches and atmosphere of beneficence—the most surprising pieces will be her early self-portraits, five of which are shown. When she was sixteen and under the influence of the impressionists and Matisse, she had begun studying fine art in Stockholm. Later, she moved to the Ateneum in Helsinki, which she left after a few months—having had trouble with male tutors who dismissed her ambitions as a painter. In pictures like Smoking Girl (1940) and Lynx Boa (1942), loosely painted with short impressionistic dabs of color, she answers back, showing herself as a defiant young woman with an almost contemptuous look on her face. The expression of hauteur shows up again in Family, a picture from 1942, in which she stands imperiously over her mother Signe and her father Victor—both successful artists but neither, the picture seems to say, as successful as Tove will be.

Advertisement

Alongside the realism of these pictures runs another, more fantastical, vein. In the 1930s, she made a number of paintings in gouache which have the quality of dark fairytales. In Sleeping in the Roots, eight creatures, halfway between pigs and puppies, lie curled up in the hollows at the foot of a tree, their air of cosy contentedness threatened only by the roots themselves, which strike into the red earth like forks of lightning. In other pictures from this period, the gloominess is more overt and the mystery more pronounced. In Midwinter Wolves, a dark tornado swirls over the sea as a ghostly figure in the foreground is stalked by a pack of black canines, while in Landscape a group of figures looking utterly lost in a vast landscape sit among imaginary trees whose flowers resemble, variously, candle flames and plumes of smoke.

One of the pleasures of the exhibition is being able to trace the origins of the moods and styles that would show up later in the Moomin books. The original cover of The Moomins and the Great Flood featured a picture, also in gouache, showing Moominmamma and her son Moomintroll making their way through a forest lush with outsized flowers and haunted by black figures watching their progress from behind the trees. In Comet in Moominland (1946), a comet threatens to destroy Moominvalley. Jansson draws Moomintroll and his friends Snork, the Snork Maiden, Sniff, and Snufkin sleeping peacefully on a mat surrounded by low-hanging jungle fruit while the comet looms in the sky above them. It’s an image that is at once magical and doom-laden.

The mix of disaster and gentle naïveté that runs through the Moomin books can also be traced back to Jansson’s political cartoons, which often captured the violence of war as seen through a child’s eyes. On the cover of Garm from July 1941, Santa Claus prepares to descend with his bag of gifts to a landscape strafed by fighter planes, helped down by a cherub and a quartet of fearful angels. Like the Moomin hiding from Hitler on her 1944 cover, these childhood figures act as a chorus of confused but indomitable innocents. Their persistence during a time of crisis contains a promise of rehabilitation, of the kind that Jansson depicted in a set of public murals commissioned after the war, which are included in the exhibition’s catalogue. This optimism is carried through in Moominpappa at Sea (1965), where the Moomin family, after traveling to a remote island that turns out to be rocky and weather-beaten, is shown drenched but hopeful, having a picnic in a driving squall.

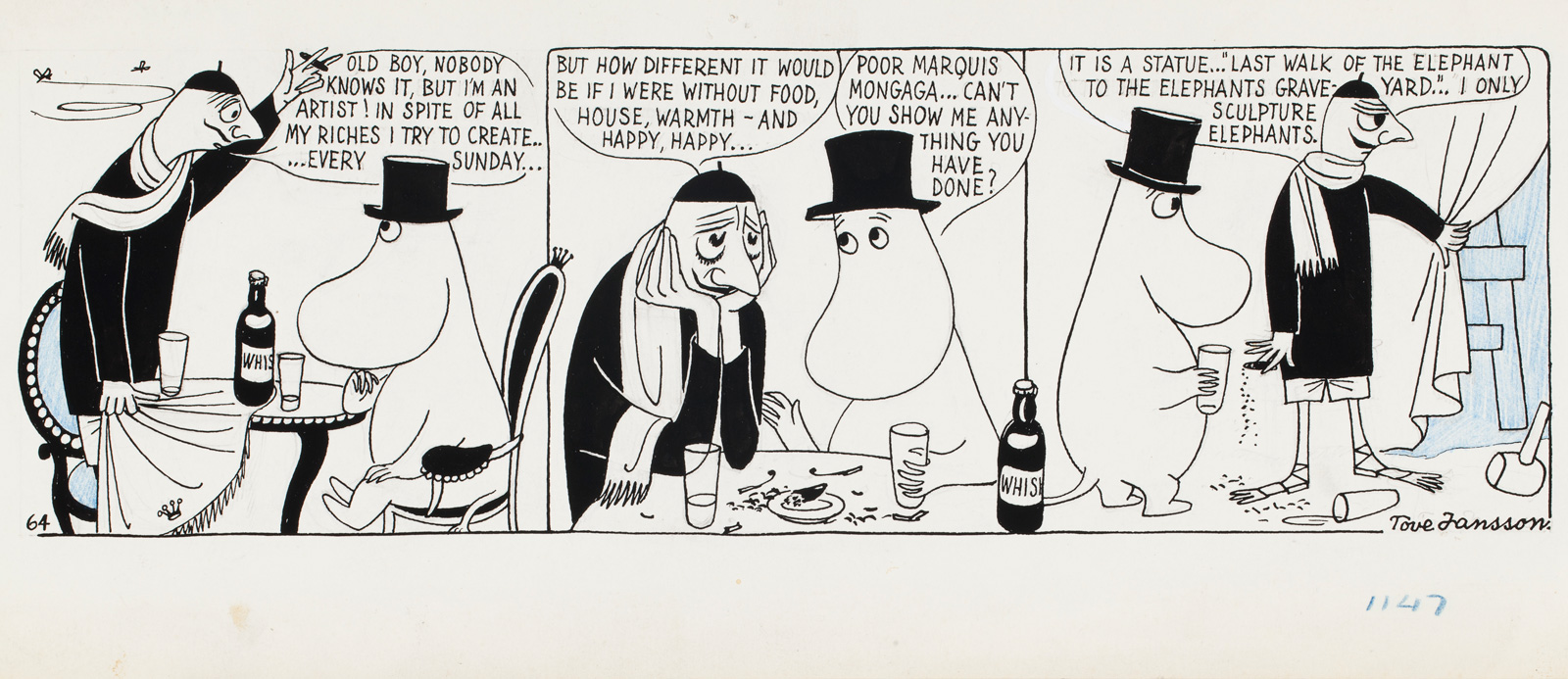

At several points in the exhibition, the curators have displayed multiple versions of the same image next to each other to show Jansson refining her drawing until it’s just right. On a single strip of paper, for example, she reworks the figure of Moominpappa, crouching expectantly, trying to extract the last drops of paraffin from an empty can. On a pair of adjacent sheets, she depicts him opening the front door during a storm to find a soaking wet muskrat outside. In one version, the rain comes down in a misty wash; in the other, it pours in long, incessant streaks. There is a stylistic as well as an atmospheric connection between Jansson’s paintings. Like her paintings, her drawings show her debt to impressionism. The dense arrangement of short lines creating shadow, cloud, or heavy weather is a technique borrowed from Van Gogh, who did the same thing with oils in pictures like Evening Landscape with Rising Moon (1889).

By the time Jansson returned to painting later in her life, hoping to resurrect the career she had started before the war, abstraction was in vogue, and there was little appetite for her work. A trio of abstract seascapes from the 1960s, the wild water sketched in with rough slashes and blocks of paint, show her adapting her style to the times. But the critics were unenthusiastic about the paintings, and had her pigeonholed as an artist for children. A late self-portrait, from 1975, has an air of defeat about it, of timorous, red-eyed exhaustion a long way from the confident figure of thirty years before. And yet, walking through the show, you are left feeling that while the Moomins may have given Jansson less time than she would have liked to work on her other material, she was wrong about their relationship to it. Rather than being a distraction from her proper work, they were a distillation of it.

Advertisement

“Tove Jansson (1914-2001)” is at the Dulwich Picture Gallery through January 28, 2018.