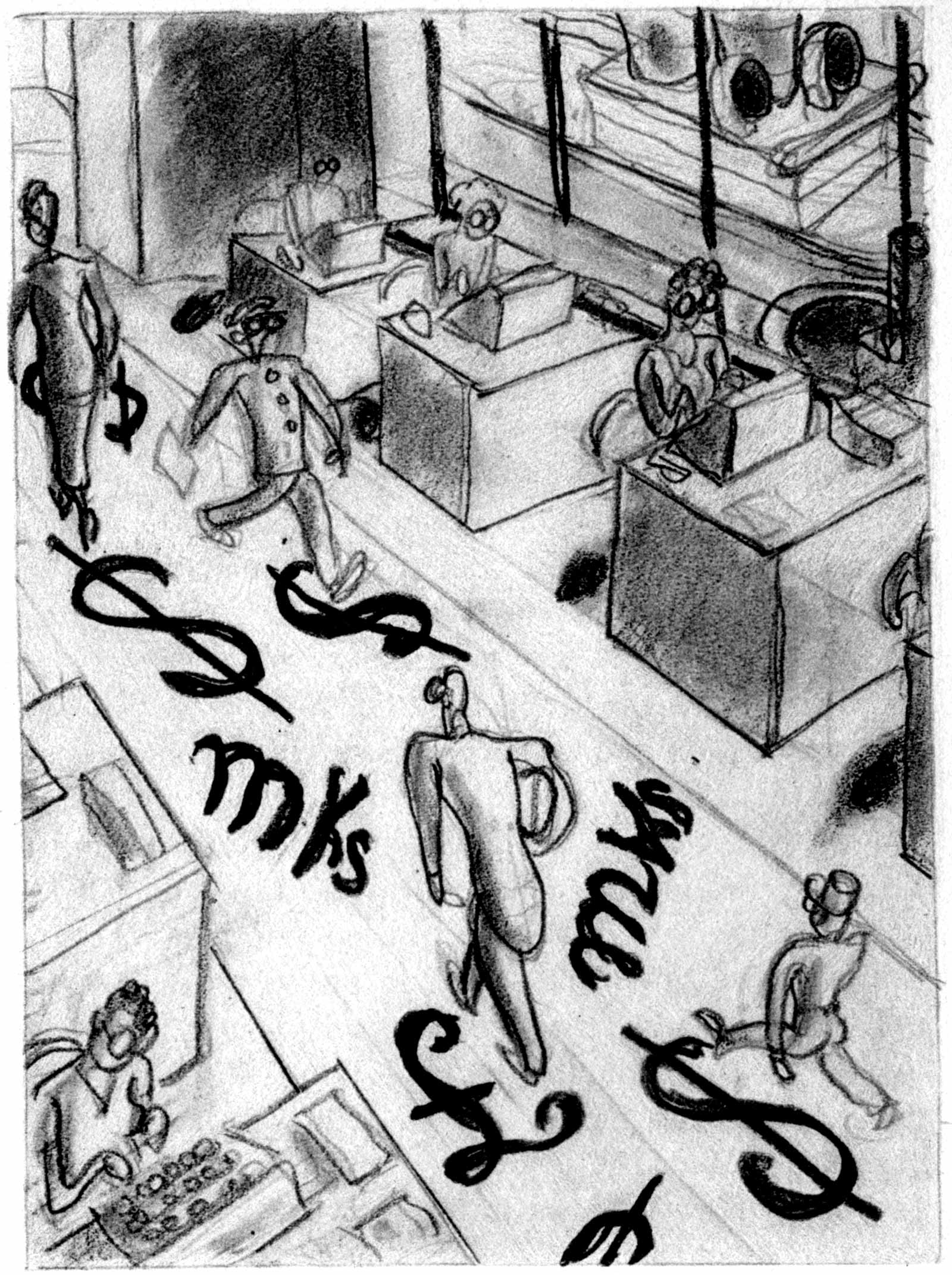

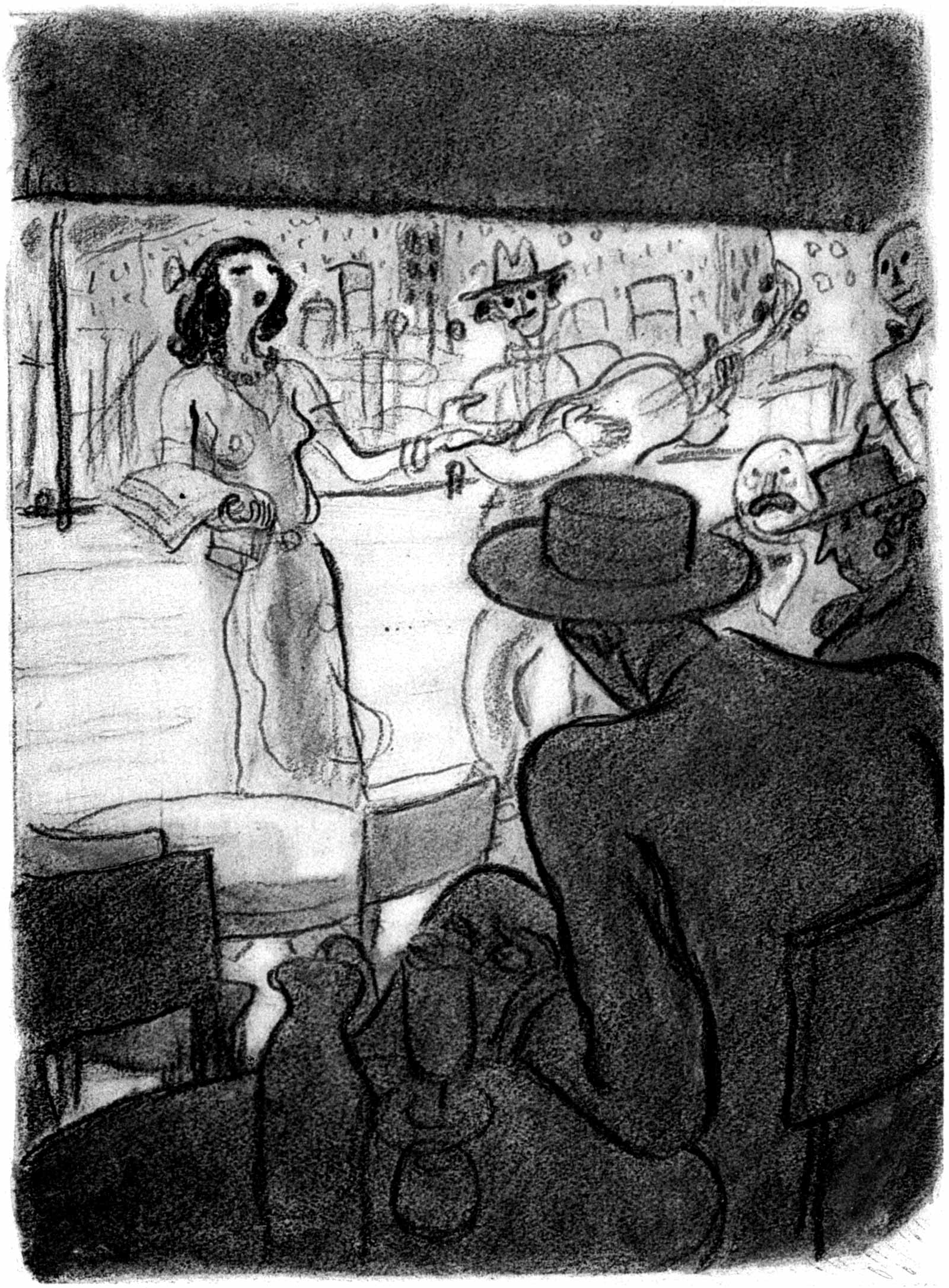

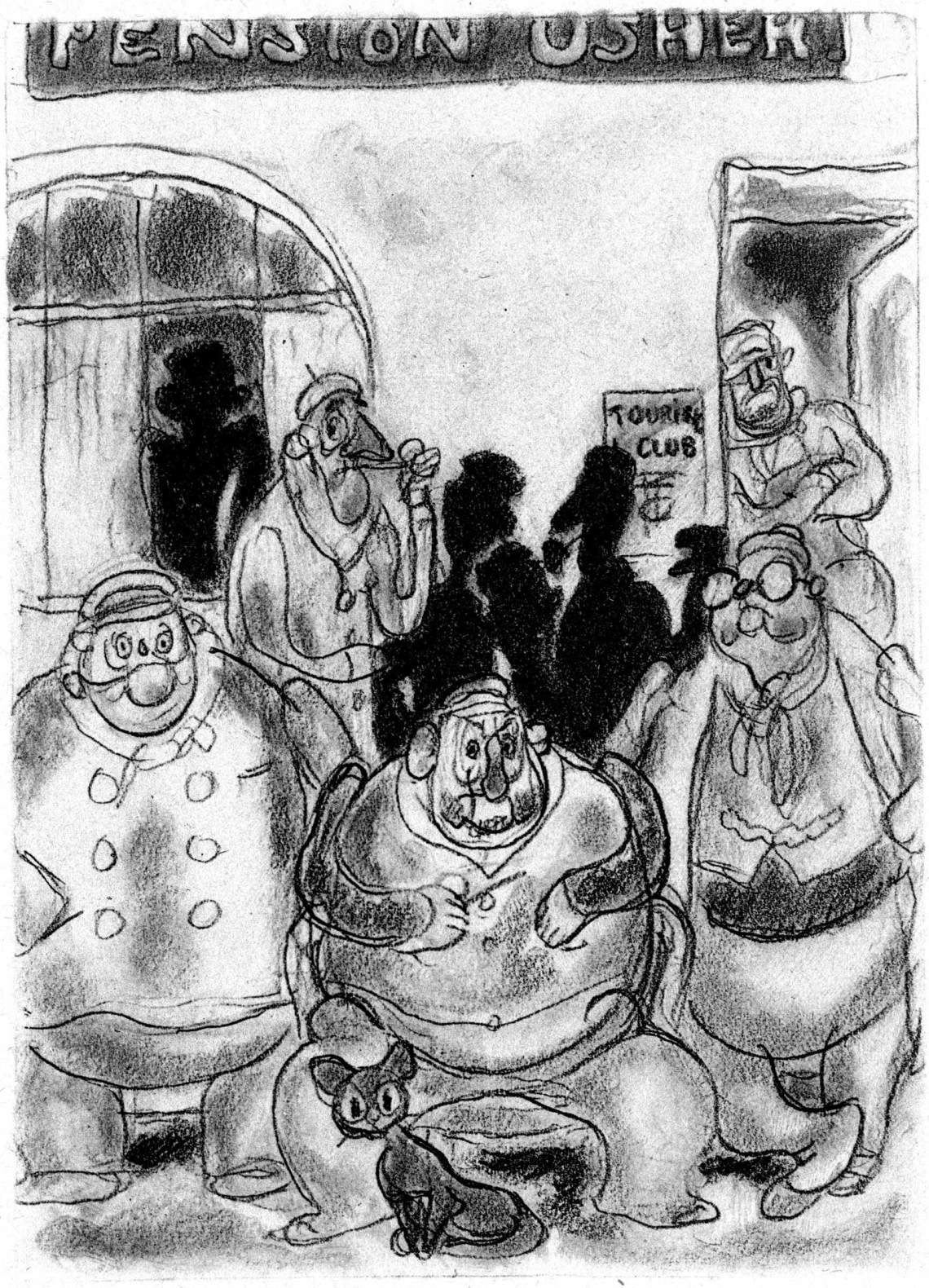

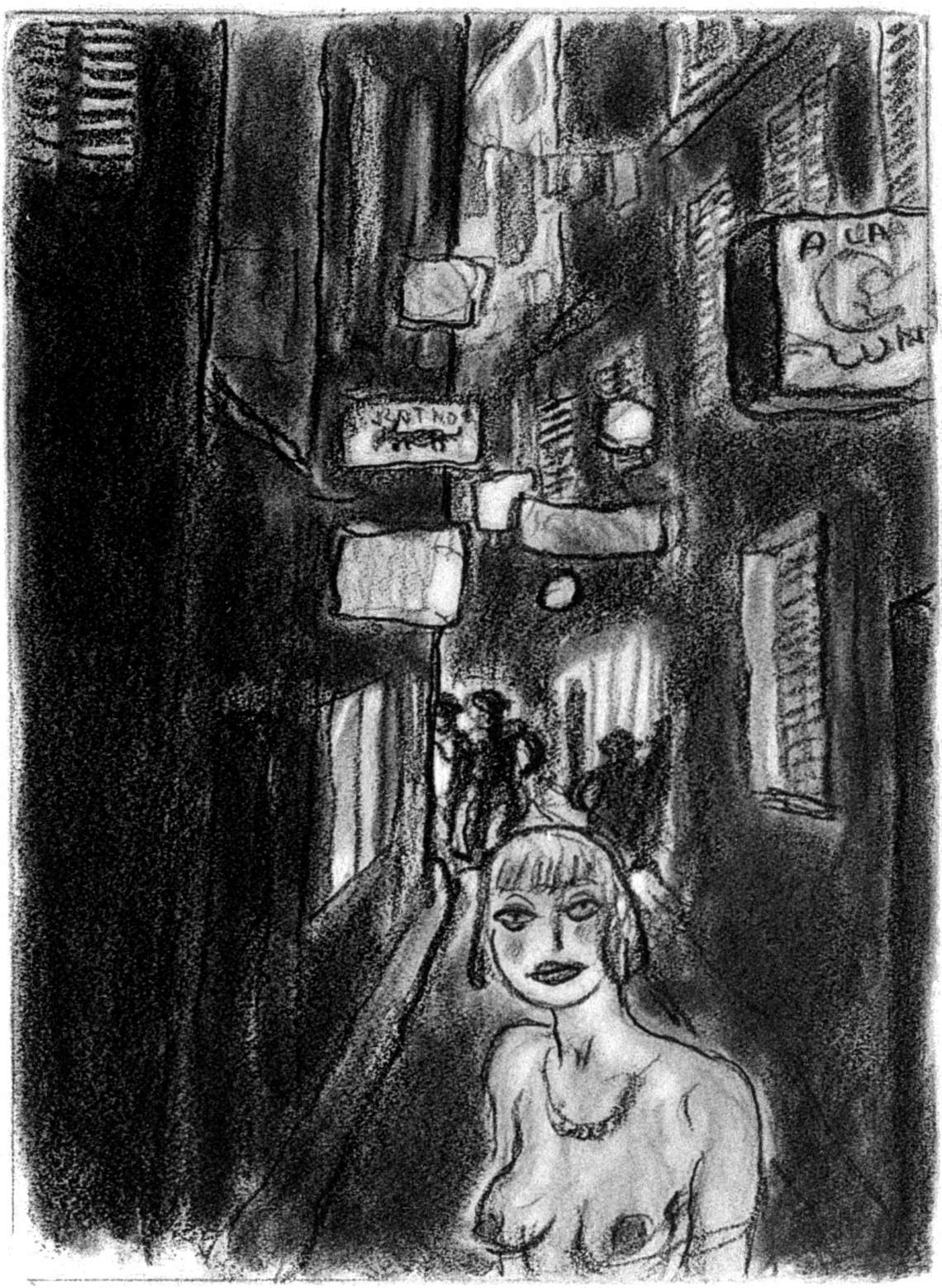

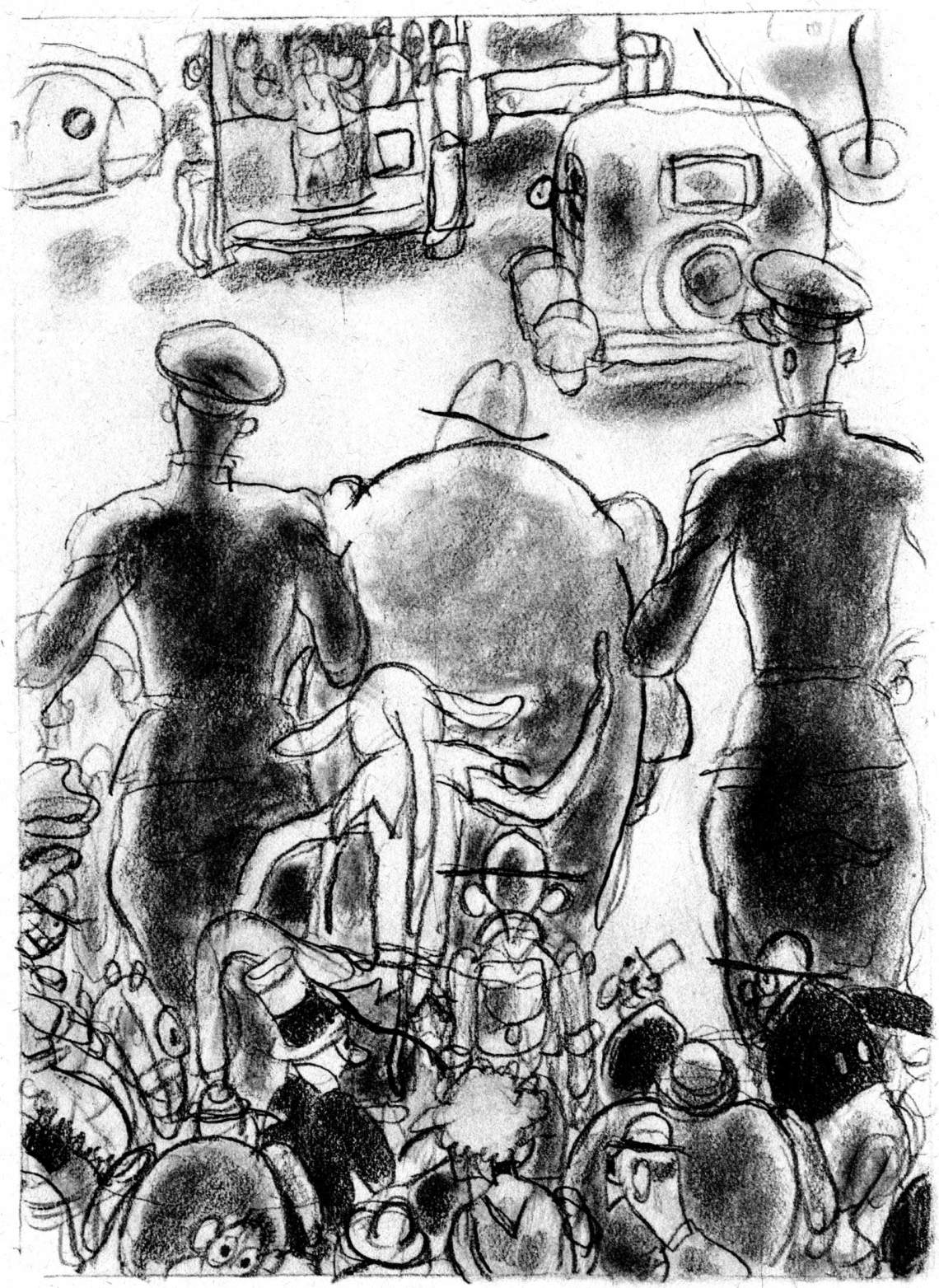

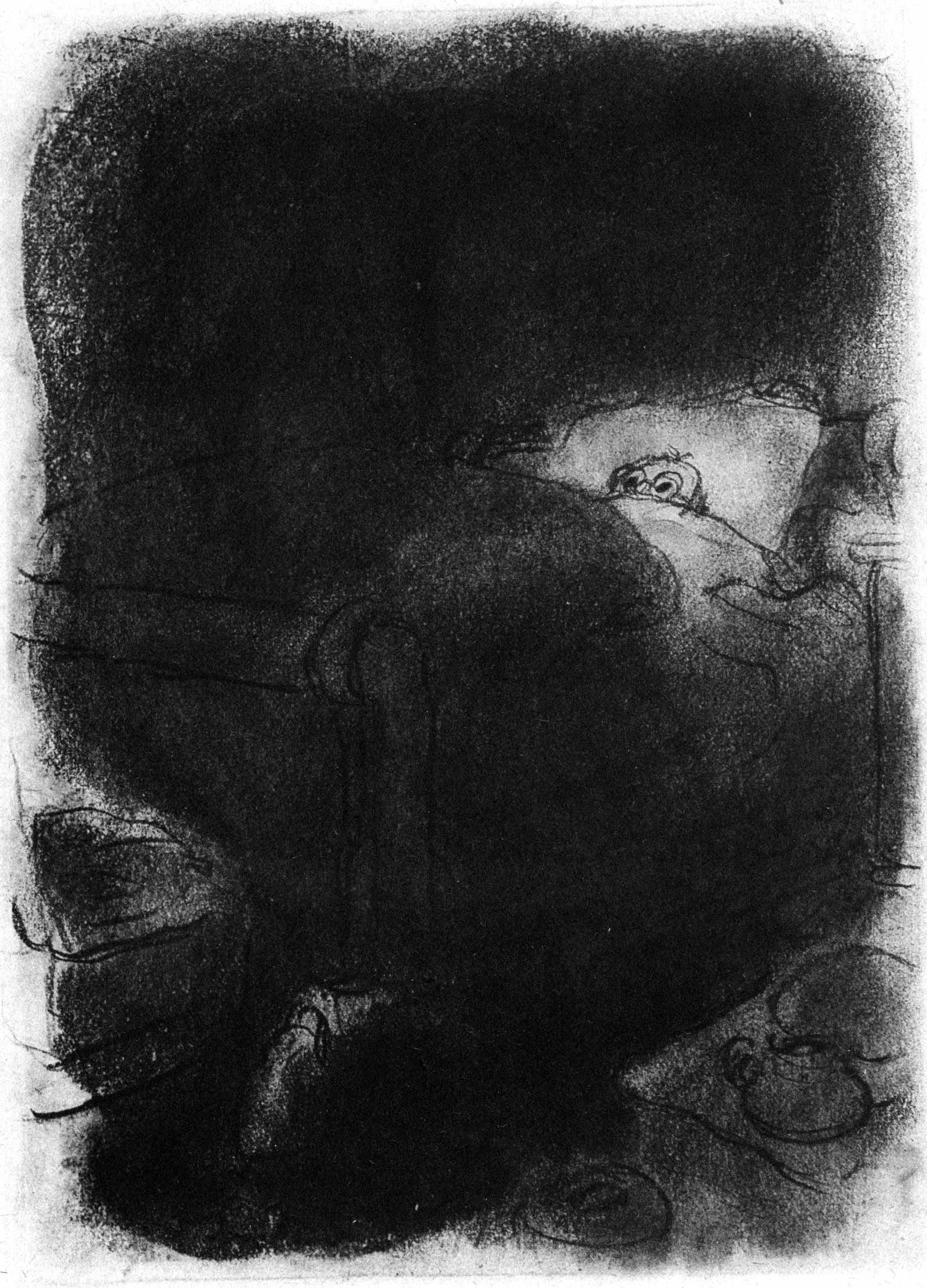

When the French artist Gus Bofa died in 1968, his obituary in Le nouveau planete described him as “a profound thinker… a bilingual philosopher who knew how to tell us about fear in words and images.” As an editor, writer, and illustrator, Bofa stands at a crossroads between numerous art forms: book illustration, comics, poster-art, aphorisms, and visual biography. Bofa’s drawings evoke the anxious spirit of the early twentieth century, images of urban alienation and war but also of fantasy, a mixture he shared with his friend the novelist Pierre Mac Orlan. Words, either Bofa’s or others’, are central to his oeuvre. His drawings suggest the existential darkness that overtook a Europe defaced by war and modernization. The illustrations he made for Mac Orlan’s moody novel of espionage Mademoiselle Bambù—of spies, prostitutes, sailors, and drifters—compliment the tale of a web of interconnected characters as they circulated around Europe’s port cities, a depiction of the dark unease of the early twentieth century. Bofa’s contributions appear in rough black and white, sketch-like, as if somehow disappearing into themselves. In these drawings, his style is dark, almost resembling the aesthetics of film noir, though at times it is also goofy or playful.

Bofa himself has become as obscure as the shadowy figures that populate his drawings. Some of that can be attributed to the fact that toward the end of his life, when he could have consolidated his reputation, he withdrew from public life and became a virtual recluse. Another is the marginal place that a book illustrator receives in literary history. He has enjoyed a minor revival in France, where his books are now collectors’ items, particularly because of his influence on bande dessiné. In 2000, thirty-two years after his death, an exhibition about his collaborations with Mac Orlan was mounted at Musée de l’Abbaye de Sainte Croix at Les Sables d’Olonne, in western France. Throughout the last decade, Éditions Cornélius has reprinted a number of his books and published a biography of him by Emmanuel Pollaud-Dulian in 2013. Although, at first glance, Bofa’s work exists in the tidal zone between the French political cartoons of the nineteenth century and the bande dessiné of the twentieth, on closer scrutiny it has more affinity with modernist literature, a characteristic apparent in his collaborations with Mac Orlan, which also foreground a less examined aspect in Bofa’s work. Since his revival in France, Bofa’s influence on French illustration has been well documented; less has been written about his significance in the history of French literature.

Born Gustave Blanchot in 1883, Bofa was drawn from an early age to visual art and writing. He grew up in Bordeaux until his father, a military officer, moved the family to Paris, where the young Gustave finished his schooling. Around the time of the family’s move, Bofa started signing his childhood works with initials only, which he claimed stood for “Gus Bofa.” The name suggests boyish mischief: “gus” can mean “rascal” in the Niçoise dialect, which the critic Emmanuel Pollaud-Dulian suggests his mother may have spoken and thus Bofa may have heard as a child, while the phrase faire un bofa can mean “to be a failure.” After finishing his education, Bofa focused his attention on the visual arts, though he still read copiously. At seventeen, after knocking on the door of the editor of Sourire, Bofa began drawing for that weekly, still up to mischief by signing “G. Bofa.” By the time Bofa was in his mid-twenties, in 1909, Le Figaro described him as a “master.” That year, he also took on an editorial position at the illustrated popular weekly Le Rire.

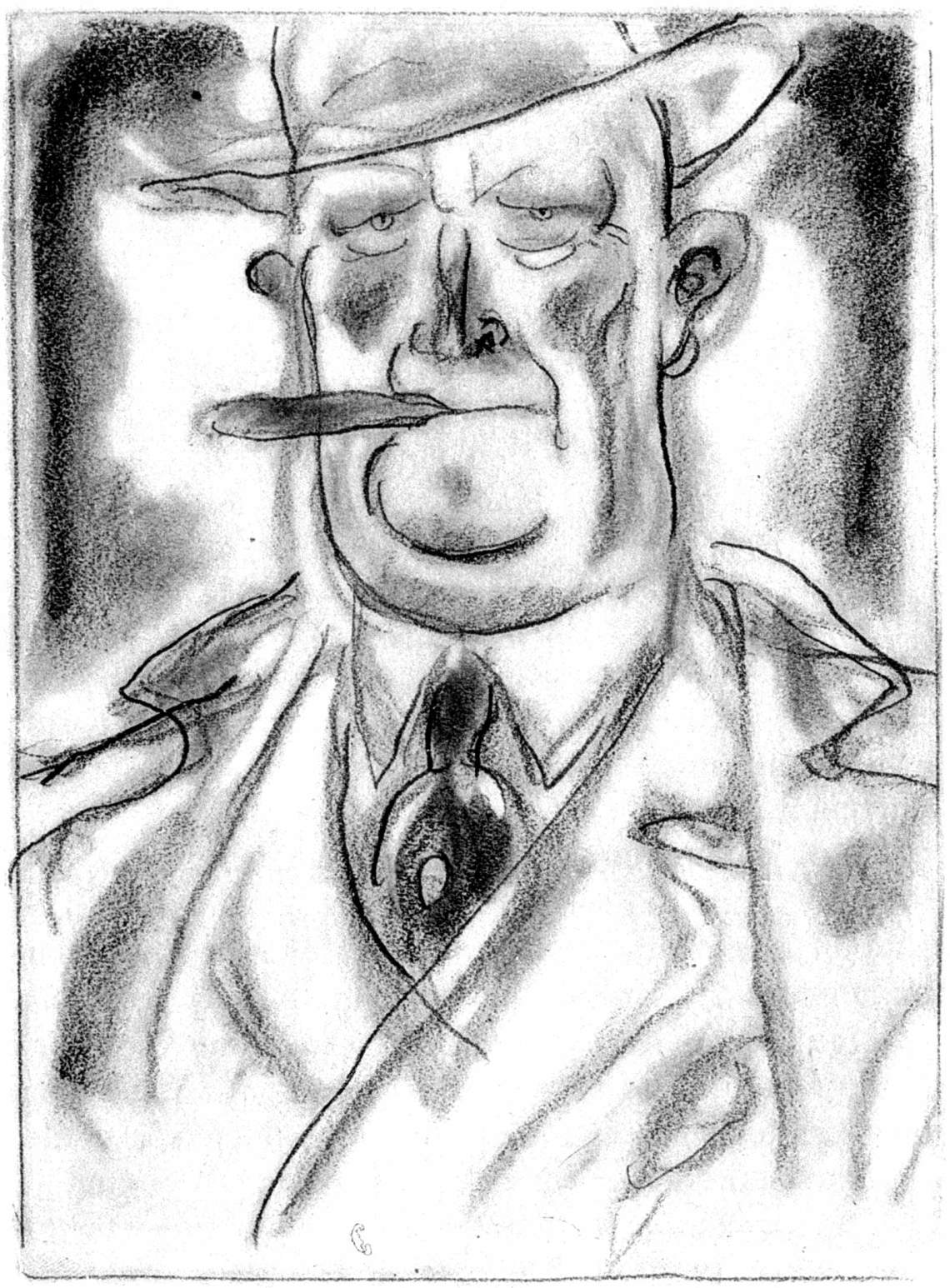

During the World War I, Bofa continued to further his reputation as an illustrator. For La Baïonnette, he drew satirical images of the front, where he was stationed until he was wounded and discharged. His drawings are frank, and do not conceal the brutality of war and its effects on soldiers. Afterward, he started publishing short books of illustrations with text, some written by him, such as Slogans and Synthèses Littéraires et Extra-Littéraires. Slogans, for example, paired aphorisms about human nature, often ironic, with comedic sketches, while Synthèses contained portraits of writers and other notables. He also started illustrating the books for which he would become best known, including those of Mac Orlan.

Bofa’s engagement with the author of Mademoiselle Bambù began with a kind of reversal. Hoping to sell some drawings to Le Rire, Mac Orlan approached Bofa. Instead of accepting Mac Orlan’s drawings, Bofa invited him to write for the magazine. Mac Orlan, who would later be described as “le Proust des pauvres,” would go on to publish novels that sit somewhere between avant-garde and potboiler, and which have been admired by Raymond Roussel and Guy Debord among others. Those works often track what the author called “the social fantastic”: the idea that the traditional tropes of fantasy such as magic and mythical creatures could not encompass the way modern life engendered its own monsters: serial killers, spies, con-men, drifters. Bofa’s visual style and sensibility was an ideal match; they produced more than ten books together.

Bande dessiné, as we now know it, did not exist when Bofa was making his most important work. Although significant, his association with “BD” has now overshadowed other aspects of his oeuvre. If not exactly a writer, Bofa is a modern artist whose work constantly crosses boundaries between the visual and verbal arts in idiosyncratic ways. His drawings suggest an alternative meaning for the dubious term “paraliterary”—a word that has, for other reasons, unfairly haunted the reputation of Mac Orlan as well, whose work has at times been miscategorized as escapist adventures. His mixing of media and his emphasis on mass-produced art were essential elements of Bofa’s modernism.

Bofa’s longstanding collaborations with Mac Orlan, on a variety of projects, extended his range. Mac Orlan praised Bofa as the ideal illustrator for “the social fantastic,” while Bofa once claimed that the two were so in synch that Bofa could draw as Mac Orlan wrote, his illustrations perfectly matching the subjects of Mac Orlan’s text.

An avid reader throughout his life, Bofa also contributed book reviews in the 1920s and 1930s to Le Crapouillot; these include essays on André Gide, Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner, Louis-Ferdinand Céline, and Blaise Cendrars. Though unremarkable, Bofa’s literary criticism reveals his sympathy for modernist writing, even when he was critical of it, in the case of Faulkner’s Sartoris, or in his critique of Gide’s Soviet sympathies. More importantly, Bofa became renowned during this period for illustrated editions of literary classics—Thomas De Quincey’s On Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts, Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, Baudelaire’s translations of Poe, and Cervantes’s Don Quixote. Of these, Bofa’s brilliantly colored Quixote is considered a masterpiece of book illustration.

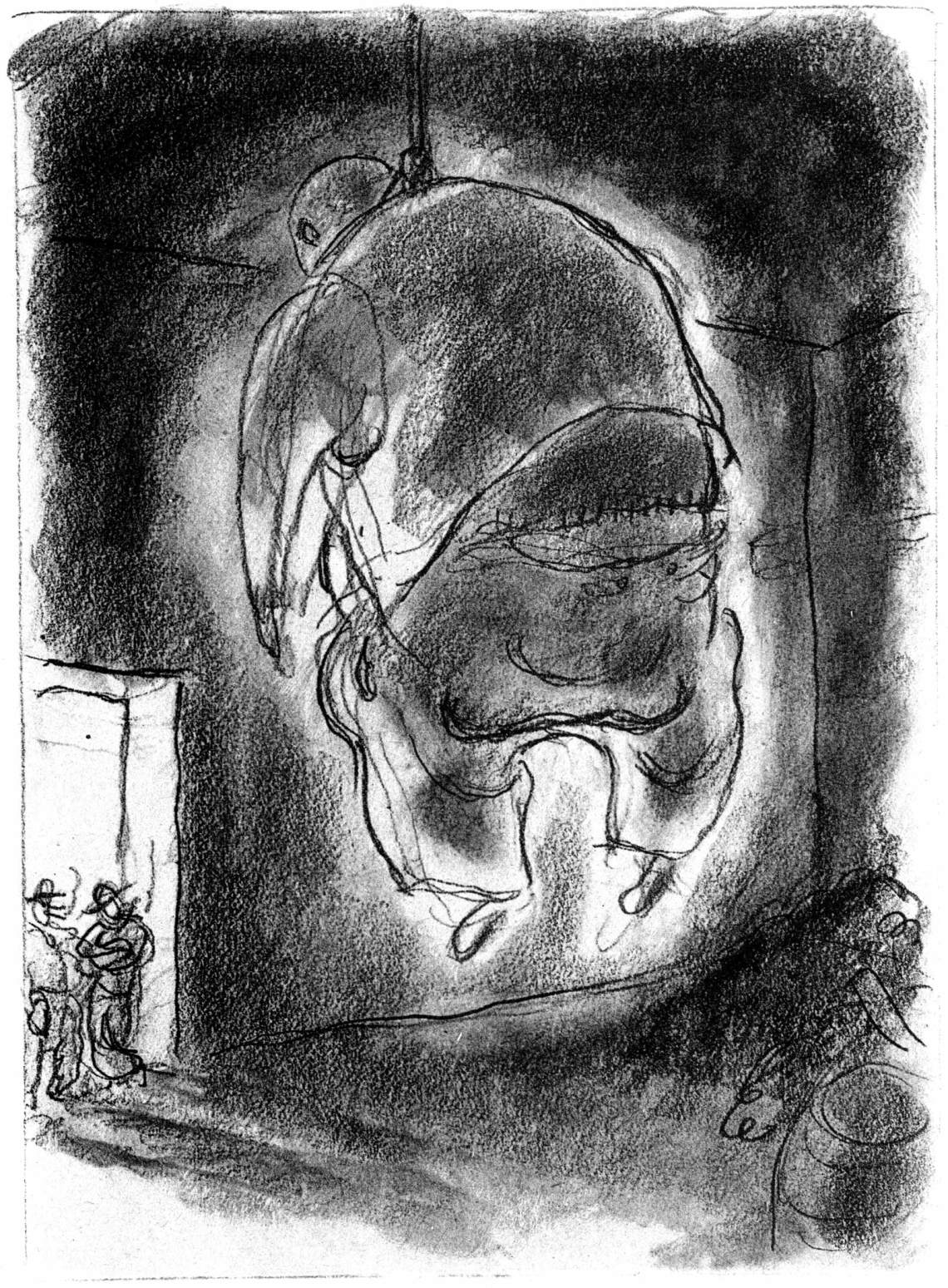

Much the way he chose to keep a nickname he’d given himself when young, Bofa preserved a childlike quality throughout his oeuvre that walks side-by-side in many of his illustrations with a very adult fear. In one cartoon-like rendering of Père Barbançon, one of the central characters of Mademoiselle Bambù, he is depicted hanging from a noose. A morbid imagination runs deep in Bofa, one rooted both in childhood and in the nightmares of the twentieth century. As a boy, he set up a make-believe graveyard in his family’s garden, where he would hold pretend funerals for family members, even their cat. Bofa’s drawings often began in an odd way: throughout his life, he made puppets on which he used to model his figures. They are strange, creepy-looking things. It’s almost as if his drawings originate from monsters. In both word and image, the fear is there. As Mac Orlan wrote in Le quai des brumes, “All of us possess, deep in the dark night of our thoughts, an abattoir that reeks.”

Adapted from the afterword, by Aaron Peck, to a new translation, by Chris Clarke, of Pierre Mac Orlan’s Mademoiselle Bambù, which is published by Wakefield Press.