“When you write my epitaph,” Elizabeth Bishop famously told the poet Robert Lowell in 1974, “you must say I was the loneliest person who ever lived.” The sentiment was hardly new for her. She had written, between 1935 and 1936, in an untitled poem she never published, that her life to come should be associated with a heavy, pelagic solitude: “The future / sinks through water / fast as a stone, / alone alone.” Yet, for all the sea-weight of her sadness, she sought to protect and preserve her solitude, as aloneness, she clarified in a brief essay in 1929, was a special state—distinct from loneliness—that we should cherish. “Why is it,” she asked, “that so many of us seem to dread being alone?”

Composed when she was only nineteen and still in school, “On Being Alone” suggested that many people had forgotten how to be alone, were even, she suggested, terrified of solitude. The essay spoke to me in a special way when I read it for the first time this year.

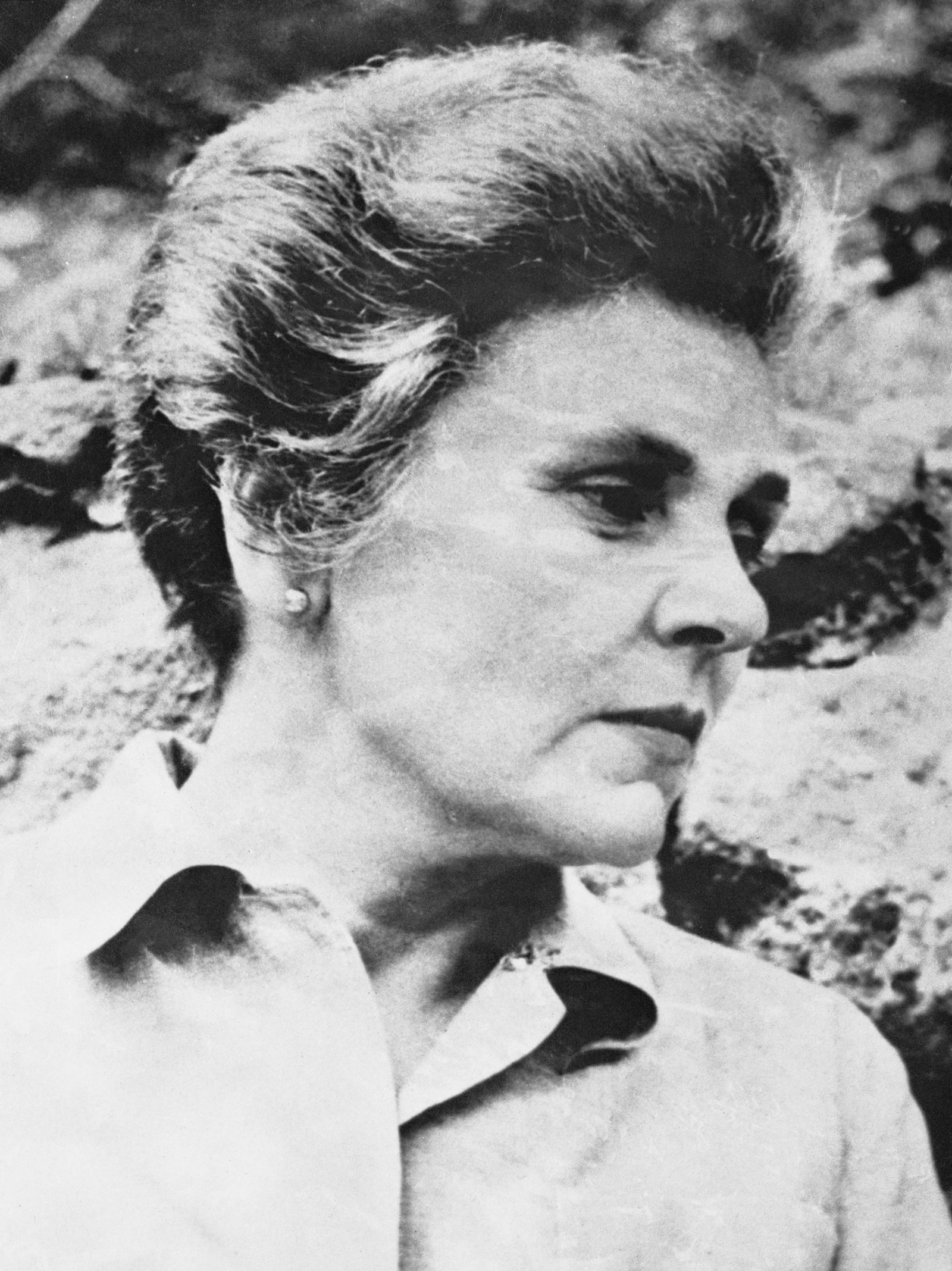

From a young age, Bishop had felt lonely. Her father died soon after her birth in 1911, and Gertrude May Bulmer, her increasingly distant mother, who was suffering from psychiatric illness, ferried her between family homes in Massachusetts and Nova Scotia, until Gertrude was committed to an asylum. The last time Bishop heard her mother was just before Gertrude was hospitalized, when she let out a lingering, chilling, almost unearthly cry that Bishop heard while driving a cow to pasture.

As a child, Bishop was molested by her uncle, George Shepherdson, an abrasive, even sadistic man who once dangled her by the hair over a second-story balcony; she found her Aunt Florence excruciatingly “foolish.” When Bishop went off to school at Walnut Hill and, later, Vassar, she avoided returning home for the holidays, begging her aunt and uncle to let her instead vacation with the girls with whom she had become infatuated, or sometimes even renting rooms alone in local hotels. When people inquired about her mother, Bishop simply told them that her mother was dead, perhaps to avoid revealing a truth she found embarrassing and isolating. She had always been shy; her conflicted feelings about her family offered her a chance to say even less, at least about them.

Poetry, like the boys and girls (but primarily girls) she flirted with, became a refuge, a way to quiet old screams. Bishop, despite despising labels in general, agonized over how to categorize her own identity. She did not openly identify as queer—she did not like being “typed as a lesbian,” she told the poet James Merrill—yet her desires for women were clear to her. She did not know if she was “really” a poet and sought encouragement from others, most of all, in her youth, from Marianne Moore, who proffered Bishop supportive, nourishing critiques of her poems. Yet even after Bishop’s poems began finding publication, she told Moore she was considering medical school rather than writing. She had inherited some wealth, yet she did not feel, despite her pearl earrings, able to fit in with the richer, more self-assured girls at school.

Unmoored, seemingly unable to find a simple life-path, she frequently felt isolated and lonely. “Can it be,” she asked in a later poem, “House Guest,” of a lugubrious seamstress who wished instead to be a nun, “our fates will be like hers,/ and our hems crooked forever?” In a sense, this was Bishop, the self-effacing girl who rarely believed she could make the seams of her life line up.

But being lonely and being alone are not the same, and Bishop recognized from a young age that there was something special, even salvific, about the latter. “There is a peculiar quality about being alone, an atmosphere that no sounds or persons can ever give,” she wrote in the 1929 essay. “It is as if being with people were the Earth of the mind, the land with its hills and valleys, scent and music: but in being alone, the mind finds its Sea, the wide, quiet plane with different lights in the sky and different, more secret sounds.” I understood this sentiment well, the special beauty of the blue hours when you are, by choice, alone, and the candle of your self burns in a way it never quite can when you are with someone else. “But,” as Bishop acknowledged, many people “are frightened” of solitude. “Why does being alone,” she pondered, “present such a great trial, or why should we wish to keep the conversation going so endlessly? The fear of a ‘quiet hour’ alone,” she continued, “is greater than the fear of all those innumerable quiet hours alone that are ahead of all of us.”

Advertisement

Far from dull quietude, she argued that aloneness was a kind of entry into adventure; it is to “go on voyages of discovery” to “find the islands of the Imagination.” Aloneness can be comforting, if you understand its shadow-language, its candlelit corridors, its night-sky vastness. It can even, Bishop suggested at the end, be a kind of presence in and of itself, a “companion in ourselves who is with us all our lives… the rare person,” she wrote, now seemingly describing her own inner avatar of aloneness, “whose heart quickens when a bird climbs high and alone in the clear air.”

As an only child who was frequently by herself and who was also, for many years, deep in the closet, I understood well what Bishop was describing. And, at times, I’ve felt that precisely because I desire time to myself, I don’t quite fit into the modern world of social media, where it often seems that allowing yourself solitude suggests something negative—that you’re struggling with something, or hiding, or tormented, or just somehow “off.” Instead, aloneness can be a beautiful privilege we may grant ourselves in the moments when it is possible to disappear, lanterns lit, and silently voyage to islands on no map.

*

Bishop’s solitude served multiple purposes. Sometimes, it saved her; at other times, it pained her. Sometimes, hiding seemed necessary. Keeping to herself could be a form of self-preservation in an era when queer love was still very much “the Love that dare not speak its name,” as Lord Alfred Douglas famously put it in “Two Loves,” an 1894 poem wielded against Oscar Wilde during Wilde’s 1895 obscenity trial. Bishop feared being marked a lesbian, particularly in the repressive atmosphere of McCarthyite America, when the government boasted of an anti-gay campaign known as the “purge of the perverts,” in which security officials in the State Department bragged about firing queer employees—sometimes one a day, which was twice the rate of dismissals for supposedly lacking political fealty. Because of this fanatical crusade, between 1945 and 1956, six thousand government employees found themselves fired over their assumed homosexuality. Although this campaign for “morality and decency” primarily targeted male employees, women who sought government jobs were still very much at risk, as one could be suspected of being a lesbian due to not dressing “femininely enough” or simply for living with a female roommate.

Authors like Patricia Highsmith feared that being labeled a “lesbian-book writer” would be career suicide; these were the days, as Highsmith noted in a 1989 afterword to her seminal lesbian novel of 1948, The Price of Salt, “when gay bars were a dark door somewhere in Manhattan, where people wanting to go to a certain bar got off the subway a station before or after the convenient one, lest they be suspected of being a homosexual.” While Bishop knew some lesbian couples and queer writers, she remained wary that her literary fame in America would cause her to be outed. Her move to Brazil in 1951—initially envisioned as a short vacation—offered some respite, as Brazil, to Bishop, seemed somewhat more tolerant. But nowhere afforded her full freedom.

Since Bishop couldn’t suppress her desires, she lived in a world of contraries, a state all too many queer writers of her era knew well. At once exuding courage and exalting an almost Victorian ideal of discretion, Bishop lived and frequently traveled with her distaff lovers, yet she described them, in writing and conversation, as “my friend,” “my hostess,” or even as a “secretary,” rather than as a lover. Despite—or perhaps because of—her ineradicable shyness, many of the women she was drawn to—from her school-day loves, like Judy Flynn and Margaret Miller, to the Brazilian modernist architect and landscape designer Maria Carlota Costallat de Macedo Soares, nicknamed Lota, who captured her heart decades later—were just her opposite: confident, social, and soignée, moths drawn to the luminous lanterns of soirees and extroversion.

Bishop wrote about the quiet ecstasy of being kissed in bed and waking up next to someone beloved—but never published these more revealing poems. “Breakfast Song,” a paean to her last lover, Alice Methfessel, begins “My love, my saving grace, your eyes are awfully blue. I kiss your funny face, your coffee-flavored mouth”—but it would have been lost if a friend of Bishop’s, Lloyd Schwartz, hadn’t found it by chance in one of the poet’s notebooks. When Bishop was on her deathbed, she asked Methfessel to destroy their love letters, to expunge any incriminating evidence of her amatory inclinations. (Methfessel, fortunately for scholars, preserved some.)

Up to the end, even when she had begun to hear Death’s wings, she was thinking of hiding.

Advertisement

I understood Bishop’s overwhelming, at times almost paranoiac, fears. In the second grade, I had my first crush, Olivia, a brown girl with dark pigtails—but even then, I vaguely wanted to imagine holding her hand as another girl, not as the boy people kept referring to me as. I grew up in a Caribbean island where my desires—to be perceived as female, firstly, and to be able to love people of any gender, but other girls most of all—seemed impossible, if not infernal. These were the deadly temptation plots of the Devil, as I occasionally heard in priests’ sermons on Sundays. I lacked the language for who I was; I didn’t even know the word “transgender” existed until I learned it, years later, as a college student in America.

For the first two decades of my life, I hid who I was, tried to bury my desires, fearing I would be beaten up in this life and tortured in Hell eternally in the next if I acted on them. I tried, like Bishop, to make the seams of my life look straight from the outside—even if those seams never fit, but instead chafed and cut at me. For years, I felt depression take hold of me, possess me, like some quiet, gray demon. In my adult years, like Bishop, I occasionally drank alone in my apartment to try to stop the depression from taking hold—though, of course, the wine and whiskey only made it worse.

But as an only child, I had had plenty of time to myself, and so I also learned to escape by fantasizing. In the worlds I imagined, I was a girl with another girl—or, once in a while, a boy—at my side. In my time alone, I learned to sail away, as Bishop did, to an elsewhere-place—and sometimes I think I would not have survived if I had not had the outlet of my alone time, my imagination. My solitude nourished my writing, and writing often helped me cope, but it couldn’t take away my depression from feeling that I was living an ugly lie. At my lowest point before coming out as trans, I was about to end my life by drinking poison—and then, unlike Bishop, I decided I had to take the risk of openly living my truth. I came out in my mid-twenties, having chosen to stay in America rather than return home, since America, at least, seemed to offer me a chance to live as that woman-loving woman of my constant dreams. But without what Bishop identified, the deep saving grace of quietude, I doubt I would have lived long enough to come out at all.

*

Bishop almost lost Lota, the woman who would alleviate her loneliness for over a decade, before they even grew close. She had first met Lota and her then-partner, the former dancer Mary Morse, in New York in the late 1940s; Bishop fell for Morse and sent her a drunken confession of desire, for which she then swiftly apologized, fearing Lota’s indignation. Despite the incident, when Bishop, years later, decided to travel to Brazil to escape for a bit, Lota offered Bishop her apartment overlooking Copacabana Beach; Lota and Morse would be gone to Petrópolis for a month. Brazil overwhelmed Bishop at first, however, and she considered leaving for Buenos Aires.

A fruit kept her near Lota. After biting a cashew fruit, Bishop’s body swelled and became inflamed. For days, Lota, having returned to her apartment, nursed Bishop back to health, taking her to the hospital for daily injections of calcium. Bishop was self-conscious—she did not want to impose, did not want to seem some clueless, grotesque termagant—yet she found her barriers dropping around Lota. Soon, she was infatuated.

“Lota!… Come scratch me again! I am madly in love with you,” she wrote on the back of a draft of a never-completed short story, “Homesickness.” Morse moved out. When Bishop had convalesced, Lota gave her a gold ring and proposed that they live together. Bishop’s sojourn in South America had transformed into the setting for her new home.

Yet loneliness still afflicted her. She struggled to speak Portuguese conversationally and was accustomed to being abandoned by Lota’s friends when they tired of her halting speech or did not want to use English. She had no friends of her own in Brazil. When Lota was contracted to construct a colossal park along Guanabara Bay, she became so consumed by work that Bishop faded from her life, and Bishop, feeling deserted, began anew the heavy drinking that had debilitated her before. She also had affairs in Brazil and Seattle; when Lota found out about the lover in Seattle, she broke down and ended up hospitalized. In 1967, in New York, where Bishop had fled to give Lota space, Lota claimed she was well enough to visit, then committed suicide by overdosing on sedatives. Her death, which Lota’s friends blamed on Bishop, almost broke Bishop entirely. She recovered only in 1970, while teaching at Harvard, when she found Alice Methfessel, a slim, twenty-seven-year-old secretary with extraordinarily blue eyes.

But Bishop was still unstable. Alcohol and drugs—Nembutal for insomnia, Dexamyl her “pep-up cheer-up” pill—became her near-constant companions, supplanting, all too often, the companionship of the cherished solitude she had once lovingly spoken of. Suddenly, that aloneness seemed loud with old screams, miasmic with the scent of cemeteries. When she was away from Alice, she wrote petrified letters about how much it hurt to be apart. “I’d be a wreck without you,” Bishop told her. Left to her own devices, Bishop collapsed multiple times in stupors, sometimes requiring hospitalization. When Methfessel revealed that she had become romantically involved with someone else, a man named Peter, Bishop took the rejection badly. “The art of losing isn’t hard to master,” Bishop declared, after this latest loss, in her most famous poem, “One Art,” “though it may look like… disaster”—and, under the weight of her loneliness, her life indeed seemed a phantasmagoric disaster.

She had become almost afraid of aloneness, like the very people she had criticized in her essay so many decades earlier.

*

Bishop’s poems could paint strikingly clear images, as in “The Fish,” but they were, as often as not, exercises in concealment. Although Marianne Moore had described Bishop’s poetry as “archaically new,” some of her most sensual published work hid its subject in crystalline labyrinths. “The Shampoo” is a tender, subtle reflection on washing Lota’s slowly silvering hair—the white strands are “shooting stars,” but the final lines are more down-to-earth, asking Lota, with a sweet familiarity, to “[c]ome, let me wash it in this big tin basin”—and despite the fact that the poem’s never-gendered subject is only ever described as “dear friend,” Bishop feared that the poem might be “indecent,” too explicitly queer. Consequently, her most naked depictions of love, like “Dear, my compass” (which ends with her and her “dear” going “to bed… early, but never / to keep warm,” suggesting interpersonal intimacy), remained unpublished until her death.

Even if what she wrote sometimes aggrieved her, her poems, like her privacy, often had a lenitive effect on her life, helping her cope and even, perhaps, becoming brief talismans against pain. She remembered how it had felt to hear her mother shriek, how it had hurt to be rejected. She did not want to relive those memories. Poetry, it turned out, could express her pain as much as it shielded her from it, at least for a moment.

There is nothing wrong with a shell of shyness, or a shroud we choose to wrap around ourselves sometimes. I don’t enjoy those times when the possessing, demoniacal gray of depression makes all the world seem lonely. Yet, as Bishop wrote in 1929, being alone—which is quite different—is unimpeachably special, sacrosanct. The art of being alone, especially in a world where our identities all too often feel coterminous with what we post on social media or achieve publicly and how people react thereto—and where desiring privacy can seem a cause for suspicion—feels increasingly hard to master. But it’s one of the most exquisite, and, to me, most necessary, arts to master, lest we lose too much of ourselves by forgetting—or never knowing—how to be beautifully alone, buoyed by the ocean-music of silence.