In her introduction to London: Aspects of Change (1964), Ruth Glass wrote that the city was “too vast, too complex, too contrary and too moody” to be known entirely. The same could be said about Glass herself, an urban sociologist based at University College London from the 1950s to her death in 1990. She left no archive for scholars to sift through. The term she coined, gentrification, has become ubiquitous, but she remains out of sight. Her longtime friend, the late Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm, described her as a “tiny, combative, bird-like woman.” She always dressed in blue.

Glass’s London, the London of the early Sixties, is at once distant and strangely familiar. The capital’s seemingly inexhaustible postwar growth threatened to suck the rest of Britain dry. “As London becomes ‘greater,’” Glass wrote in London: Aspects of Change, “the dislike, indeed the fear, of the giant grows.” Vast stretches of the city, from Notting Hill to Islington, were losing their working-class character, becoming accessible to only “the financially fittest, who can still afford to live and work there.” Shabby Italian restaurants became sleek espresso bars. “Modest mews and cottages” transformed, Cinderella-like, into “elegant, expensive residences.”

But this was no fairytale. “Once this process of ‘gentrification’ starts in a district,” Glass wrote, in the first recorded use of the term, “it goes on until all or most of the original working-class occupiers are displaced, and the whole social character of the district is changed.” Glass attributed these changes to increasing state support of private real estate development, as well as the relaxing of rent control laws. While the culture of postwar affluence had blurred the old social distinctions, she argued, a new divide was fracturing society.

Glass’s description of gentrification would transcend its origins, becoming shorthand for the spatialization of class struggle. Articles on gentrification inevitably invoke her name before turning to Spike Lee’s Do The Right Thing (1989), which chronicled the early stirrings of gentrification in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn; warehouses-turned-condos; and the rise of NIMBYism. The reembourgeoisement of the city is arguably the prevailing dynamic of twenty-first century urbanism. Yet gentrification was just one aspect of Glass’s work—work that was informed by her fight for social justice.

When London: Aspects of Change was first published in 1964, Ruth Glass was fifty-two years old. The author photo that accompanied the book depicts a younger Glass, somewhere in her early thirties. She is wearing heavy enameled earrings and her dark hair is pulled back. She looks strikingly glamorous, but her expression contains the hint of a smirk. The photograph suggests a woman with absolute confidence in her abilities.

Glass was part of a wave of Jewish intellectuals that fled Nazi Germany for Britain in the 1930s. Born Ruth Lazarus in 1912, she began her career as a teenage journalist for a radical paper in Weimar Berlin, mingling with young intellectuals at the bohemian Romanisches Café and studying at the University of Berlin. She left Germany in 1932, just before the Nazis came to power, and studied in Prague and then London, where she finished her degree at the London School of Economics.

She was young, foreign, a committed Marxist, and, for a brief period between her marriages to, Henry Durant and David Glass, respectively, a divorcée. She was also a pioneer in her field. Her first major publication, Watling: A Study of Social Life on a New Housing Estate (1939), published when she was twenty-seven, examined “associational life” on a London County Council estate, whose residents had been relocated from the cramped living conditions of the East End. From 1948 to 1950, Glass worked for the Ministry of Town and Country Planning, conducting research on New Towns—planned communities intended to rehouse metropolitan populations in better living conditions—before returning to academia. Her later work on community life in the East London neighborhood of Bethnal Green, coauthored with the sociologist Maureen Frenkel, led to a flurry of academic interest in the area, culminating in the founding of the Institute of Community Studies in 1954. Led by the pioneering sociologist Michael Young (himself later known for popularizing a famous coinage: meritocracy), the Institute conducted studies of local life via interviews and ethnographic research, becoming the center of “community studies” in urban sociology.

On the whole, Glass’s work drew on survey data and statistical analysis. Her methods were honed during two years in New York, where she earned a master’s degree from Columbia and worked at the Columbia Bureau for Applied Social Research, a social science research center. Beyond the rows of figures and tables, though, lay an urge to grasp something ineffable—what it meant to belong. Her Watling housewives had been uprooted from the bustle of inner London to an isolated housing estate. According to a local newsletter, “It was like being in a foreign country, with new friends to make and new difficulties to overcome.”

Advertisement

Glass brought her own experience to bear on the plight of her subjects, middle-aged women who found themselves suddenly marooned in their suburban homes. “Whoever has been a stranger in a strange place will testify to the relief in being in the company of people whom one might have met at home,” she wrote in Watling.

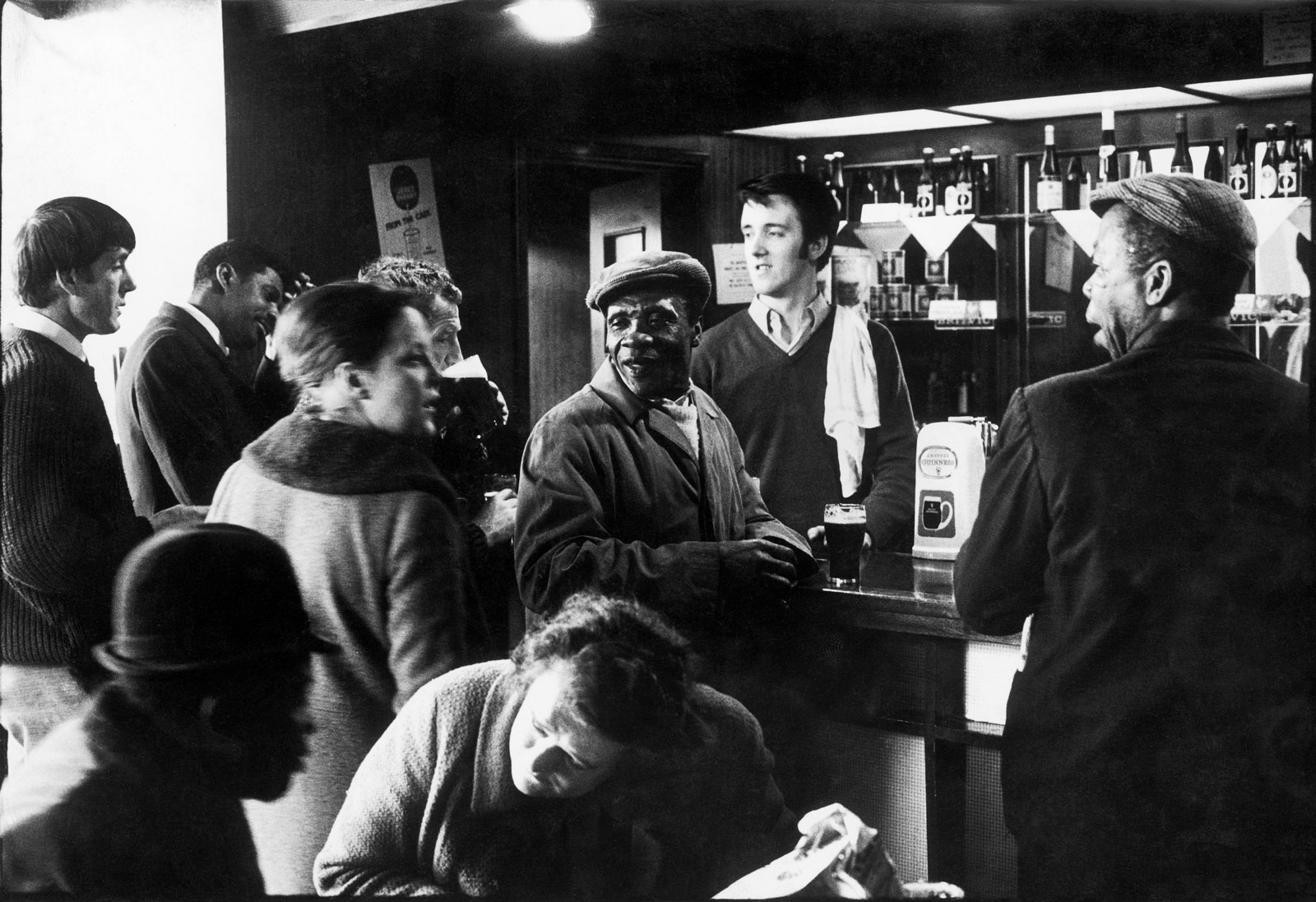

These themes would inform her work on West Indian immigration to London. Later referred to as the Windrush generation, nearly half a million West Indian migrants came to Britain in the 1950s and 1960s, encouraged by labor shortages in healthcare and public transport. Assisted by the historian Harold Pollins, Glass analyzed a sample of response cards collected by the Migrant Services Division of the Commission for the West Indies—data on migrants’ experiences securing work and shelter. In London’s Newcomers: The West Indian Migrants (1961), she drew on this data to describe the challenges faced by the West Indian community, notably discrimination in work and housing.

Against the backdrop of the 1958 Notting Hill riots, when racial tensions between white and Afro-Caribbean residents culminated in brutal anti-black violence, Glass argued that the notion that non-white immigrants were flooding British cities was false, and belied by empirical evidence. The real “colour problem,” she claimed, was the persistent discrimination faced by non-white Britons in work and housing. She went on to excoriate what she termed the “benevolent prejudice” of British society—one that condoned discrimination as long as it didn’t rise to the level of violence.

Glass’s work was not without its flaws. In a review of Newcomers in The Spectator, the sociologist Peter Marris noted that Glass’s book failed to include firsthand accounts from West Indian migrants themselves, though she could easily have conducted interviews with her subjects. In a 1960 Independent Television News segment on West Indian integration, Glass comes across as one of the armchair liberals she despised, warning in patrician tones against complacency in the face of racial strife. She characterized the Notting Hill riots as “disturbances.”

Yet despite these limits to her work, Glass was an outspoken voice for social justice. Her research was aimed at inspiring social change. She called for legislation to prevent race-based discrimination in employment and housing, measures that were eventually realized in the Race Relations Act of 1968, which did just that. While Labour politicians quietly endorsed immigration controls, Glass fiercely opposed the restrictions on non-white immigration put in place by the Conservative government in 1962 and tightened by Labour in 1968. In testimony to the Royal Commission on Local Government in Greater London (1957-1960), she argued for administrative structures that corresponded to socially-defined areas rather than imposing a top-down model for the capital. In the absence of archival correspondence, the extent and impact of her political advocacy remains difficult to gauge, but her work was always embedded in a broader social context.

The question of belonging, above all, ran through her work. “They look in two directions at once,” Glass wrote of the West Indian migrants she studied, “backwards to their Caribbean homes and forward to their new life in Britain.” But Glass’s own past remained sealed away, her German “rust[ing] through persistent disuse.” In his obituary of Glass, Hobsbawm would write that “Ruth did not look backward.” Whether born out of her experiences of anti-Semitism in Britain or simply the desire to assimilate, Glass’s resolve to move forward was unwavering.

Her intellectual confidence often came across to colleagues as abrasiveness. As the historian Mark Clapson has documented in Anglo-American Crossroads: Urban Planning and Research in Britain, 1940-2010, Glass was often dismissed by the American colleagues with whom she collaborated on urban research for the Ford Foundation in the 1950s, many of whom did not share her “leftish sympathies.” The sociologist Edward Shils called her “aggressive”; the Ford official Francis Sutton described her as emotionally volatile. These impressions were colored by her status not only as a woman in a male-dominated profession, but as someone who was, in the words of her former student Michael Edwards, “incapable of arse-licking.”

As a consequence, Glass’s academic life proved precarious. While her husband David was ensconced as a professor of sociology at the London School of Economics, Ruth bounced from department to department at University College London, in a series of impermanent research positions. Under her leadership, though, UCL’s Centre for Urban Studies produced groundbreaking studies on urbanization in the developing world, anticipating the accelerated urbanization of cities in the Global South. Many of these studies focused on India, which she visited every year and whose politics she commented on for the socialist periodical Monthly Review, critiquing the caste-based affirmative action programs in government employment ushered in by the 1980 Mandal Commission as insufficiently ambitious. Yet despite the salience of this work for reorienting urban studies towards the Global South, the Centre for Urban Studies disbanded before her death.

Advertisement

The most telling line in Hobsbawm’s obituary is his description of Glass as “an all-purpose ball of fire, though what she increasingly reduced to ashes was herself.” Marginalized in a male-dominated academy, Glass struggled to carve out space for herself, her intellectual output suffering as a result—a phenomenon identified by a growing body of work as workplace precarity. Yet even beyond coining gentrification—the term that outlived her—Glass set the agenda for a generation of postwar social scientists, breaking new ground in both the study of race relations and in community studies. In an increasingly divided world, where the fragmentation of community has shattered older notions of belonging, and where backlash against immigration is reshaping the political landscape, Glass’s work resonates more than ever.