The only person I have touched in a week is my two-year-old daughter. Every selfie I take of us is a photograph of me trying to inhale her. The streets outside are empty, the ambulance sirens constant, the sunshine an insult. Beyond our windows, the city is running out of ventilators. Stores have signs in their windows that look lifted from the apocalypse films I loved back when I thought they were metaphor rather than prophecy: due to the spread of COVID-19 we are indefinitely closed. My daughter and I haven’t left the apartment in four days, ever since I became symptomatic.

That’s a lie. I left once, to take the trash down. I couldn’t smell it, because I can’t smell anything—the ability vanished suddenly, along with my sense of taste; the newest symptom in the news—but when the pile of banana peels and mashed zucchini pieces became impossible to push back into the bin, I knew it was time. In the mail vestibule downstairs, I saw a man in a blue mask who’d come to pick up someone else’s laundry. When he pulled the mask from his mouth to speak, I shrank away from him. I’m sure he thought I was afraid of what I’d get from him, when really I was afraid of what he’d get from me. I was afraid to speak. I imagined the virus traveling on particles of my spit. I imagined nothing. It was all plain fact. Why couldn’t I just tell him, I have the virus? It got caught in my throat. I had a vector’s shame.

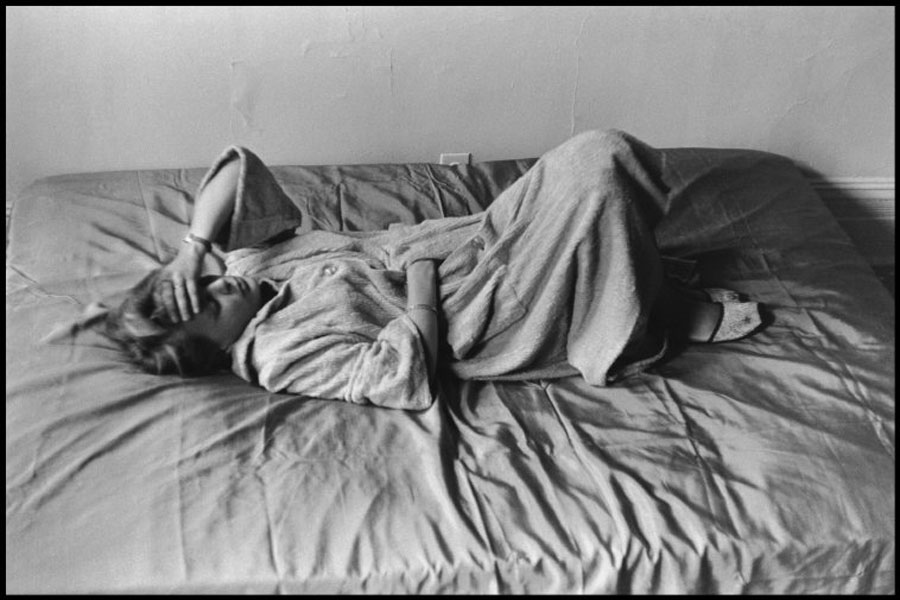

The virus. Its sinewy, intimate name. What does it feel like in my body today? Shivering under blankets. A hot itch behind the eyes. Three sweatshirts in the middle of the day. My daughter trying to pull another blanket over my body with her tiny arms. An ache in the muscles that somehow makes it hard to lie still. This loss of taste has become a kind of sensory quarantine. It’s as if the quarantine keeps inching closer and closer to my insides. First I lost the touch of other bodies; then I lost the air; now I’ve lost the taste of bananas. Nothing about any of these losses is particularly unique. I’ve made a schedule so I won’t go insane with the toddler. Five days ago, I wrote Walk/Adventure! on it, next to a cut-out illustration of a tiger—as if we’d see tigers on our walks. It was good to keep possibility alive.

They say the quarantine is tough on parents. The quarantine. As if it weren’t plural. As if we weren’t all living our own. Being a single parent is like being a parent except you’re always alone. Being a single parent in quarantine is like being a parent except the inside of your mind has become an insane asylum echoing with the sound of your own voice reading the same picture books over and over again: Mr. Rabbit, I want help. The Dark was not hard to find. Hello, Stripes. Hello, Spots. Hello, wonder. Hello, WHOA. What’s that? It’s a RUNAWAY PEA. Puffins sit on muffins. Snakes sit on cakes. Lambs sit on jams. Bees sit on keys. Little girl, you really do want help. You must do something to make the world more beautiful.

Right, yes. Today. In this doomed world. Something beautiful, for her. On our schedule, I’ve thought of many possible stimulating games, all of which are harder to imagine playing with the virus in my blood: tea party, dance party, tearing-up-tissue-paper party. I can still imagine watching the live feed from the zoo, but it’s hit-and-miss. Sometimes it’s just a koala with his eyes closed who looks ill, like the rest of us. It hardly matters what I put on the schedule anyway. My daughter knows what she likes. Her favorite game is leaping headfirst from the laundry onto the hardwood. Her second-favorite game is stuffing my bras in the garbage. Her third-favorite game is squirting diaper cream onto the floor and then handing me one of her wipes and saying, “Wipe.” When I give her A Look, she smiles slyly. “Wipe, please.” She knows the drill.

The only way I can write any of this is to sit with her on the floor and give her a pen and notebook of her own, so she can scribble beside me.

When I wake with my heart pounding in the middle of the night, my sheets are soaked with sweat that must be full of virus. The virus is my new partner, our third companion in the apartment, wetly draped across my body in the night. When I get up for water I have to sit on the floor, halfway to the sink, so I don’t faint.

Advertisement

From my window one afternoon, I see four high-school students walking arm-in-arm. There’s something pointed about their joviality, their casual touch, like, fuck you for telling us we can’t. I want to yell down at them, You can’t! Getting righteous about other people’s inadequate social distancing is how we manage our fear and justify our sacrifices. If I had to give this up, you should have to give it up, too. I haven’t touched another adult in nine days, but who’s counting. The day I realized I was sick, I posted a sign for my neighbors downstairs warning them I’ve got the plague. I’m still up at night with the vector’s guilt. Everyone who is sick is someone else’s patient zero. There is something beautifully grotesque about that phrase, shedding virus, as if with a black light you could see the sloughed-off sickness like curling snakeskins all over my apartment, crumbling to dust.

These days I usually dream about nice dinner parties I wasn’t invited to. Romanticizing other peoples’ quarantines is just the latest update of an ancient habit. So what if I signed divorce papers a month before the city went on lockdown? I’ve got my blankets. I’ve got my toddler pouring shards of pita chips down the neck of her rainbow llama pajamas, right here in the epicenter of the epidemic. Sure, I sometimes wish my quarantine was another quarantine, and I sometimes wish my marriage had been another marriage, but when have I ever lived inside my own life without that restlessness? It’s an ache in the muscles that makes it hard to lie still. Quarantine teaches me what I’ve already been taught, but I’ll never learn—that there are so many other ways to be lonely besides the particular way I am lonely.

We spend our days spearing Internet-delivered raspberries with the baby fork. “Mama help,” she says sometimes, plaintively. She needs something but she doesn’t know exactly what it is. I know exactly what I need: another human body. So I breathe her scalp again, again, again. I let her press her little toes against my thigh again, again, again. “Mama leg,” she says, delighted. Sometimes it’s enough to just name the world, to call out its parts. I can remember sex before quarantine: the opposite of distancing, the opposite of illness, the opposite of restraint. I can remember the overflowing carts at the grocery store during the days when rumors of lockdown were still rumors: the woman hoarding cat food and instant coffee, the man whose arms were loaded with soap, as if he would do nothing but clean himself until the end of time.

I can remember the last time I felt this far away from the world; also the last time I ate without tasting—at seventeen, when I came home from a week in the hospital with my jaw wired shut and my face swollen past recognition, the terrible fix for a fracture after a hiking accident. I made my mom drape sheets all over our mirrors because I couldn’t stand the sight of myself. I squirted Ensure into the gap behind my back molars with a little plastic syringe, and used a little notepad to write because I couldn’t speak for months. And what did I write? Years later, I looked back at those scribbled notes seeking profundities in the fever dream of my pain, but I just found fear and need, playing on repeat: What if I vomit while my mouth is wired shut? More Vicodin, please. More Vicodin, please. More Vicodin, please.

No Vicodin in this house. Just Baby Tylenol and bananas like mush against my tongue and another sober alcoholic on FaceTime telling me that a few of her sponsees have started drinking again because The Fucking World Is Ending, at least for now, and now rain is falling on the empty streets, and I stick my hand out the window—just for a moment, just as I press my cheek against my daughter’s belly, just to feel something that is still there.