Seventy years ago, when it was officially believed that abortion was a crime rarely resorted to by American women, one out of four were having them, according to Dr. Alfred Kinsey, since love and sex had not been outlawed as well. There were also far more deaths from perforated uteruses and peritonitis and conditions euphemistically called urinary infections than were ever reported in the papers, but each appalling story that came to light weighed upon the minds of young women of my generation.

If you lived in New York City back then and found yourself in a desperate situation, you were extremely fortunate if someone passed along the name of a Dr. Spencer, a licensed MD, who dealt with unwanted pregnancies in Ashland, Pennsylvania. Although Ashland was much farther from Manhattan than you’d ever thought you’d have to go, it was possible to get there on an interstate bus. Toward the end of your journey, the bus would travel through mountainous country scarred by coal mines with woods closing in from both sides of the road before you were dropped off in the middle of a town with dilapidated buildings and empty shop windows, where at first it seemed unlikely that your life would be handed back to you. But once you’d made your way to 531 Centre Street, the precious address you’d written to, you’d walk into an eccentric-looking waiting room filled with curios—masks from the South Seas, fishing and hunting trophies—where you’d be warmly greeted by a nurse who did not seem to regard you as a disgraceful person.

Avoiding the interested stares of the doctor’s regular patients, you’d find a seat and wait for her to take you to the remarkable Robert Douglas Spencer, a Republican, Rotarian, and free-thinker, who believed that “a woman should be the dictator of what went on in her own body.” “I just set out to help,” he told a reporter toward the end of his life, “and never gave it another thought.” Between 1923 and 1969, in addition to carrying on with his family practice in Ashland, where he specialized in treating coalminers and developed a treatment for black-lung disease, Dr. Spencer gave at least 40,000 women—wed and unwed—safe abortions. His heroes, he said, were Clarence Darrow and Thomas Paine.

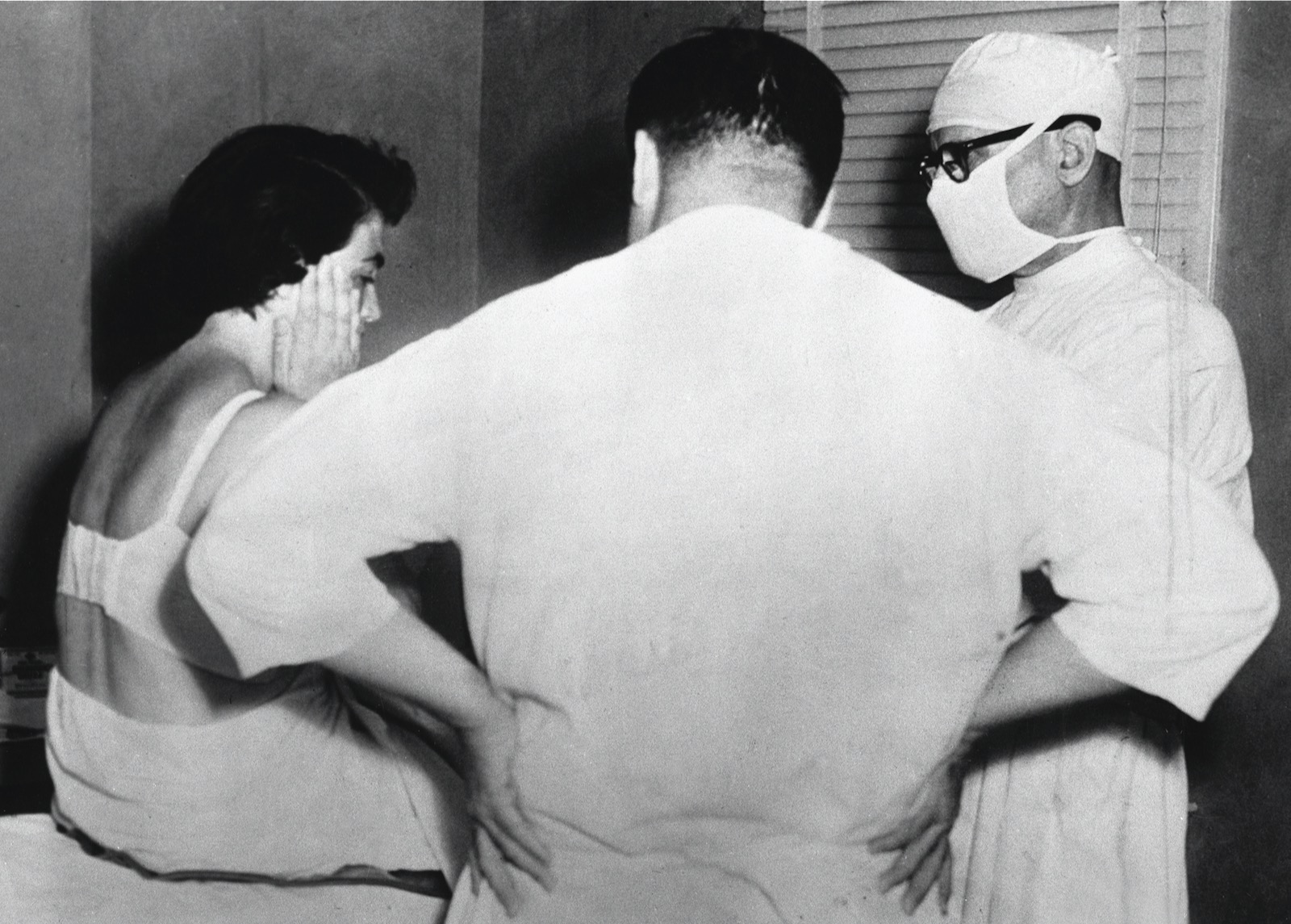

On that first visit to Dr. Spencer’s clinic, a solution of his own devising would be injected into your cervix; the following morning, before doing the curettage, he’d administer a general anesthetic, a compassionate step that was almost unheard of, since abortionists usually rushed women from the table to the door, as if there’d be a raid any minute. By the time you came to, a few hours later, you’d feel no pain. You’d pay whatever you could afford and spend one more night in Ashland before returning home, with your body intact and your human dignity restored. What women mostly remembered years afterward was Dr. Spencer’s kindness.

Over the years, the town got used to having visitors get off the bus who everyone knew were not tourists—few of those had ever come. Ashland had been depressed years before the Depression. Its main sightseeing attraction was its unusual monument to motherhood—a Whistler’s mother in bronze, installed on a hillside overlooking Route 54, with the inscription, “A Mother Is the Holiest Thing Alive.” In addition, there were a couple of places that served meals, a struggling dress shop, and a hotel and motel that always had room for white guests. The money spent by Dr. Spencer’s visitors kept all those businesses from going under. For his black abortion patients, the doctor eventually bought a building where they could stay for free.

Twice in the Fifties, the doctor was arrested for performing abortions (in one case, a woman with a heart condition had died as a result of the anesthetic); but each time, he was acquitted. Sometimes, he closed his clinic on Centre Street for a while and no one knew where he went. But he always came back. His waiting room and office became more and more crowded with the souvenirs of his travels.

As the word about him spread from one woman to another, Dr. Spencer became known up and down the Eastern seaboard as “The Saint” and “the college girl’s friend.” Women from as far away as Hollywood turned up at his clinic, even a few with foreign accents. But in order to find Dr. Spencer, since there was no way to look him up, you had to be lucky enough to be on the right grapevine.

Advertisement

I wasn’t. In the summer of 1956, when I was twenty, I needed Dr. Spencer urgently. But I didn’t have his name, or anyone else’s.

*

“How did you get yourself pregnant?” the male doctor asked the sixteen-year-old girl taken to him by her mother, who later told me the story. “In the usual manner,” the teenager replied with aplomb. It was 1983, but the doctor’s gratuitous question was a throwback to the Fifties, when it was generally felt that a woman who went out and got herself pregnant by a susceptible male deserved what was coming to her. A friend of mine who took the trip to Ashland alone in 1957, when she was twenty-two, has never forgotten the frightening moment when a car slowed down to a stop as she waited for the bus back to New York. There were a number of men in it. “You must’ve been a b-a-a-d girl!” they jeered before driving off.

I was born eighty-four years ago, just in time to grow up in the postwar period when women lost a good deal of the ground they’d gained during World War II while the men were away fighting. Once women found themselves back in the home, attitudes about keeping them there became so pervasive that there was no way for an adolescent girl to avoid internalizing them—though, once you started questioning the status quo, you were likely to continue. Although a mother might be the holiest thing you could possibly become, what if you wanted to be a novelist or a brain surgeon or an anthropologist? What if you wanted to live in your own apartment and meet all sorts of people and even see what having sex was like before you got married and had your two-point-something children? What if you wanted to run away to Paris and burn your very own candle at both ends? I was a member of the so-called Silent Generation, but beneath our silence there was turbulence.

I was raised by my mother in a state of almost Victorian ignorance about my body. Even at a women’s college like Barnard, which I attended as a day student, practical information about sexual matters was sketchy. In Modern Living, a required course I took as a freshman in 1951, we were taught the names and functions of the male and female sexual organs, as if the body were a machine without sentience, under the full control of its owner. Homosexuality, like Eros, apparently did not exist, since Dean Millicent McIntosh, who had been an officer in the WAVES during the war (there was a signup booth for naval service in a central location on campus), did not mention it. In one of her lectures, there were allusions to Family Planning, which sounded sensible to me, like budgeting, but I certainly wasn’t planning a family at sixteen.

In my junior year, when a classmate whispered she’d acquired a diaphragm, I had to pretend I knew what that was. A few of us trooped up to her room in the dorm, where she locked the door and passed around a jar in which a rubber cap that looked too large in diameter for its purpose lay dusted with cornstarch. In order to get it, she told us, she’d had to purchase a wedding ring at Woolworth’s before going to the Margaret Sanger Clinic. There, she’d filled out a questionnaire about her sexual habits, those of her “husband,” and the frequency of their intercourse, nearly every word of it made up.

I was impressed by her nerve, but all that lying you had to do was off-putting. I had been resting my faith in the condom. My scientifically minded Columbia boyfriend had recently demonstrated its capacity to withstand pressure by blowing a couple of them up into larger and larger balloons the night we both lost our virginity. I didn’t go to Woolworth’s to buy a wedding ring for my Sanger appointment until I was twenty, after I’d had my abortion.

My next boyfriend was a dangerous choice for a girl of nineteen, not that anyone could have talked me out of the feelings that overwhelmed me. He was a thirty-year-old instructor at Barnard in the midst of a divorce, who regarded himself as a liberator of young women. In order to be with him, I’d defied my horrified parents and moved out from under their roof right after graduation—not to his place, but into a tiny maid’s room of my own. I did not expect to be there very long, only until we were married.

Over the next year, he introduced me to jazz, Stravinsky, experimental film, Auden, Kafka, Wilhelm Reich, and some founding members of the Beat Generation, as well as his need for a vast amount of space in which his ceaseless search for himself could continue. Finally, he told me I was too young for him. He had just taken up with a new student of his. She was even younger than I was.

Advertisement

In the wake of all this, I managed to drag myself to my job at a literary agency, where I had to act as if my life wasn’t over in order to keep earning my fifty dollars a week. But the nights I spent by myself in my room were very bad and so were the empty weekends. On one of them, I went to a party and ran into Bill, an alcoholic recent graduate of Columbia who seemed more of a wreck than I was. We ended up on a bed in a back room. At a critical moment, Bill told me he didn’t have a condom, and feeling that everything was meaningless anyway, I let him go on. I wonder how many pregnancies have resulted from the self-destructive inertia that can come over young women who feel adrift.

A few weeks later, after counting backwards, I realized what I’d stupidly done to myself in that moment when I should have gotten off the bed. I felt so humiliated by my carelessness that it was almost a point of honor not to blame Bill, despite his contribution to my predicament.

I spent a few days in paralyzing denial; then I woke up and started frantically making phone calls. “So do you know of anyone who does abortions?” I’d ask friends, lowering my voice. It felt a little like sending out a chain letter that was going to travel outward, hit or miss. Everyone promised to ask around, but all I really learned from that flurry of calls was that pregnant movie stars went to Puerto Rico. They checked into some posh clinic there and flew back with suntans.

After a couple of weeks went by with no further results, I reluctantly consulted the graduate student in psychology from whom I was renting my maid’s room. Dorothea, who liked to take charge of things a little too much, urged me to go immediately into therapy, so that, after a few sessions, I could ask a shrink to write a letter stating that I was a mentally ill person, in grave danger of killing myself if I was forced to have a baby. This was the only thing, she swore, that would qualify me to get a legal therapeutic abortion. (I later learned I would have needed three such letters, a process that would probably have taken months; a friend who went this route ended up having a Caesarian in a California hospital, on the condition that she also have a hysterectomy.) Dorothea even had a shrink lined up for me: her rejected boyfriend, who had just opened a practice and might be inclined to do a friend of hers a favor. Before I could say yes, she reached for the phone.

For about a month, I went to him. Twice a week, I lay on his couch, waiting for the moment when he’d put down his pipe and just offer me the letter I needed, since he knew about my predicament. I was, of course, justifiably depressed, but the whole business of having to pretend that this was a symptom of insanity prevented me from producing the tears that might have helped my case. Finally, I gave up and asked if he’d authorize a therapeutic abortion. “I wouldn’t dream of it,” he said. I stood up from the couch and told him I would never come back—or pay him for our last session.

As time kept trickling away, I actually did begin to think about slitting my wrists or swallowing a bottleful of aspirin. Not that I was likely to do either, but I needed to know there was some way out, in case I never found a way to get an abortion. It didn’t make much sense, when I thought about it, that a mentally ill pregnant woman could get approval for the abortion that would save her from killing herself, but that someone in her right mind could not. It made as little sense as denying diaphragms to the very women who were in the worst position to have babies.

As for the one I was carrying, I didn’t think of it as a baby. I couldn’t afford to. I seemed to have mislaid all my feelings, apart from the terror I woke up with each morning. Yet, when I’d been with my boyfriend, I’d often daydreamed about the child we’d have. Despite my thoughts about suicide, however, I had stopped feeling that life was meaningless, since I seemed to be going to great trouble to live.

One night, the phone rang. The call was from a friend I’d known since high school. “Get a pencil,” she said. She’d run into someone who’d given her the phone number of a guy named Andy who worked in advertising. As a sideline, he enjoyed escorting women who’d gotten themselves knocked up to a doctor of his acquaintance in Canarsie. Enjoyed? But the important thing was that the doctor sounded okay.

*

I hadn’t known there were abortion middlemen, but at the time there were quite a few who’d sized up the impossible situation entrepreneurially and seen a niche they could fill. Some delivered women to their abortions blindfolded so that they would never know where they had been taken or be able to recognize the person who had treated them.

In the Sixties, even Dr. Spencer, in an effort to help more women, became entangled with a middleman named Harry Mace. This unwise arrangement forced him to raise his fee to two hundred dollars; up till then, he had never charged more than a hundred and sometimes as little as five. Flooded with the patients Mace was sending him, the elderly doctor often did three or four abortions a day—too many for his failing health and too many for the authorities to ignore. In 1969, he found himself under indictment again. He died while awaiting trial, at the age of seventy-nine.

My middleman was a much smaller operator than Harry Mace. Apart from the dollars he picked up from his sideline, he apparently derived some fringe benefits from meeting attractive young women who obviously had been sexually active.

I met with Andy on a Friday evening in P.J. Clarke’s, a bar on Third Avenue popular with admen. Wearing the striped seersucker summer suit he’d described on the phone, he showed up so late that I felt limp with relief by the time he arrived. He had one of those very close crewcuts that made him look a little like a peeled onion, I thought, as I looked up into his tanned face.

I remember obediently sipping the Martinis Andy insisted on ordering for me as he plied me with personal questions, none of them having to do with the reason I was there. As his talk grew more openly flirtatious, I had the feeling of being trapped in an unfortunate blind date I would have to play along with until he turned me over to the doctor in Canarsie. When he told me I was an “interesting combination of innocence and sophistication,” I feared that what might come next was an invitation to his house on Fire Island, to which he’d alluded several times.

“You know,” he remarked, “I’m unusually sensitive to women.” I answered politely that I could see that.

“So, don’t you like to get out of the city on weekends?”

I told him I spent weekends with my boyfriend.

“I’m surprised you didn’t bring him with you,” he replied.

When I finally brought up the abortion and asked him about the arrangements, he refused to tell me the name of the doctor, the secret that was the source of his power. “He’s a doctor who does tonsillectomies. What more do you need to know?” I came away without full confidence in the deal I’d just made, but by now I was at least eight weeks pregnant and the doctor in Canarsie seemed my only hope.

A few evenings later, I went out to Canarsie with Andy to set up an appointment and settle on the price. I remember my first sight of the doctor’s neighborhood, the rows of sawed-off-looking houses that seemed in need of an extra floor, the flights of too many steps leading to front doors high above the cemented-over yards below. It was a neighborhood where if you lost yourself, I thought, no one would ever find you.

At a house with no sign outside to indicate the presence of a physician, we were let in by a paunchy older man in a sweaty rumpled shirt, who did not look like any doctor I’d ever seen. Although he must have been expecting us, he seemed displeased by our arrival and made a point of telling Andy we’d interrupted his dinner.

There was a brusque interview in a small waiting room filled with brown furniture. Above the shabby couch where the doctor was seated was a row of diplomas behind dusty glass. I very much wanted to examine them closely but was not able to. Addressing me sternly as “Young Lady,” the doctor made sure I understood that tonsillectomies were his specialty rather than what he called “the other,” as if he did “the other” very rarely and only as a favor.

His fee would be $500, more money than I could earn in two months in my job at the Curtis Brown Literary Agency. Fortunately, since I had no savings, a friend had promised to borrow whatever I needed from the famous writer she was having an affair with, assuring him it was for a good cause. When I went to meet Andy at a newsstand in Union Square the following Friday, I had a manila envelope in my handbag stuffed with fifty ten-dollar bills.

That morning, I’d left a message at the literary agency that I’d come down with the grippe but was sure I’d be back at work on Monday. My greatest fear was that my mother would call me at work and not find me, then wonder why I wasn’t answering the phone at home. To minimize the chances of this, I’d told the doctor that my appointment had to be on a Friday. For that he’d be charging me fifty dollars extra. Fridays, Andy explained to me afterward, were the most popular days for abortions for girls like me with jobs.

*

When the day came, Andy showed up late once again, and didn’t apologize. He was in a cheerful mood—you might have thought our trip to Canarsie was going to be a pleasant excursion. I watched him stock up on the candy bars and magazines that would see him through the hours ahead. “This is how I catch up on my reading,” he said with a grin, holding up a copy of Esquire.

Once we were on the L train, although he was sitting so close to me, his thigh couldn’t help rubbing against mine, he engrossed himself in an article and left me to my silence. As the train kept stopping at stations with unfamiliar names, I’d watch the doors slide open and think how easy it would be to get off. And then I’d sit there, watching the doors slide shut again. Deeper into Brooklyn, when the train ran on an elevated track, I stared out the window into kitchens where housewives with normal lives were going about their chores.

All during that long ride, the baby seemed more real to me than it had ever been. I kept thinking about it, waiting to be born, in the red dark inside me, with its life like a sealed letter that would never be opened. But at Rockaway Boulevard, the last stop on the line, I put away those thoughts and followed Andy out of the station.

This time, the doctor immediately hurried me down some back stairs. We descended to what looked like a converted garage, where he unlocked a small room in which every surface had been covered with white towels that I could picture soaked with my blood. They seemed a sign of the doctor’s own fear of the likelihood that something could go wrong.

“I want you to remove your undergarment, young lady,” I heard him order. He watched as I complied and grew extremely agitated when he saw that I was also about to remove my shoes, “No! Those stay on!” Stretched out on his towel-covered table, I wondered, as he grasped my ankles, whether I’d actually be expected to run for it if we were raided in the middle of the abortion. After jamming my feet, beige pumps and all, into stirrups, the doctor walked out of the room. He returned wearing a white gown, rolled back my skirt, and proceeded to examine me. Then he gave me a local anesthetic, an excruciatingly painful procedure, and said it was time for me to pay him.

Perhaps it had become a ritual of his to ask his defenseless, half-naked patients for payment at this point. Perhaps this was his way of decontaminating the transaction, absolving himself of the decision to proceed.

I was trying not to breathe or do anything that might raise the level of the anger I felt directed toward me. I doubted he still had patients who came to him for tonsillectomies, or any other legal treatments, but I told him to open my handbag and just take the envelope he’d find there.

Instead, he brought the bag over and placed it squarely on the bare skin of my belly. I watched him open the envelope I gave him and count up the bills. Then he went to wash his hands and put on a mask.

The anesthetic he’d given me didn’t eliminate all the pain of what followed. All through the abortion, since I couldn’t keep my body from resisting what was being done to me, the doctor grew more and more enraged by the way my legs were shaking. Ordering me to control my “lower limbs,” he’d threaten to put down his instrument and go no further. “Young lady! If you want me to stop, I’ll stop right now!” I’d be forced to tearfully gasp, “Keep going.” He worked on me for a long time. At some point, I realized he was being very careful.

When I started feeling much less pain, I unclenched my eyes and saw the doctor carrying a basin away from the table. Shortly afterward, his hands closed around my ankles freeing my feet from the stirrups.

“You can stand up now, young lady, and put on your undergarment.”

My feet were still in the summer pumps I’d put on that morning as if I were going to the office. I didn’t think I could possibly stand, but found, after I slid off the table, that my legs would hold me up and that I could even take a step or two. I was weak, bleeding, but I’d stopped shaking.

The brick wall that had been blocking my view for months had crumbled. I could see my life once again, stretching out in front of me as the abortion, the terror, all of it started its slow slide into the past.

The doctor wasn’t quite done. “The baby was a boy,” he informed me, as he handed me some pills. A fact too raw for me to swallow and absorb. It was years before a friend pointed out that at eight weeks, he couldn’t possibly have known.

“Don’t ever let me see you here again, young lady,” were his parting words as he escorted me to the stairs.

“I have to sit down a minute,” I told Andy, who was standing near the front door, intent on leaving. I walked by him into the waiting room, close enough to the row of diplomas to read the Gothic letters of the name that had been withheld from me.

Berlucci.

My mind still hangs on to at least that part of it.

*

A few months later, I passed on that name to someone else who needed it, along with the phone number I’d gotten from Information. At Barnard, she and I had been in some of the same classes but I didn’t know her well. I told her what to expect, that she would probably be fine after her ordeal, but that the doctor was crazy and despised his patients and maybe no longer had a license.

She said she would go to him anyway. Then she got teary and embarrassed and told me she’d have to go to him alone because there was absolutely no one she could ask to take her.

I hadn’t said anything to her about Andy because the name and number I’d given her were all she really needed. I was grateful she didn’t think to ask me for anything more. The last thing I wanted was another trip to Canarsie, but I felt bad to be thinking only of myself.

“You’ll feel as good as new,” Andy had said to me in the cab that was taking us back to Manhattan, “once you forget this whole thing.” Later in that long ride, Andy had repeated this advice—this time sounding nervous, after I’d refused to go with him to Fire Island to begin my recuperation and shaken off the arm he put around me.

“Remember, sweetheart, none of this ever happened.”

I could have told my former classmate how to reach him, but because I was never going to be as good as new and didn’t even want to be, I wound up saying: “I’ll go with you.”