Many readers think of haiku, with its three short lines in a five-seven-five syllabic pattern, as a poetic form particularly well suited to evocations of nature and the open road. The prose-and-haiku travelogue of the seventeenth-century Japanese poet Basho’s Narrow Road to the Deep North comes to mind, or the Beat poet Gary Snyder’s “Hitch Haiku” (1967). A typical Snyder haiku yokes the unspooling highway to the surrounding natural world: “A truck went by / Three hours ago: / Smoke Creek desert.” And yet, some of the most moving haiku of the past century or so were written under conditions all too familiar to us at this present pandemic moment: illness, confinement, loneliness, and pervasive fear.

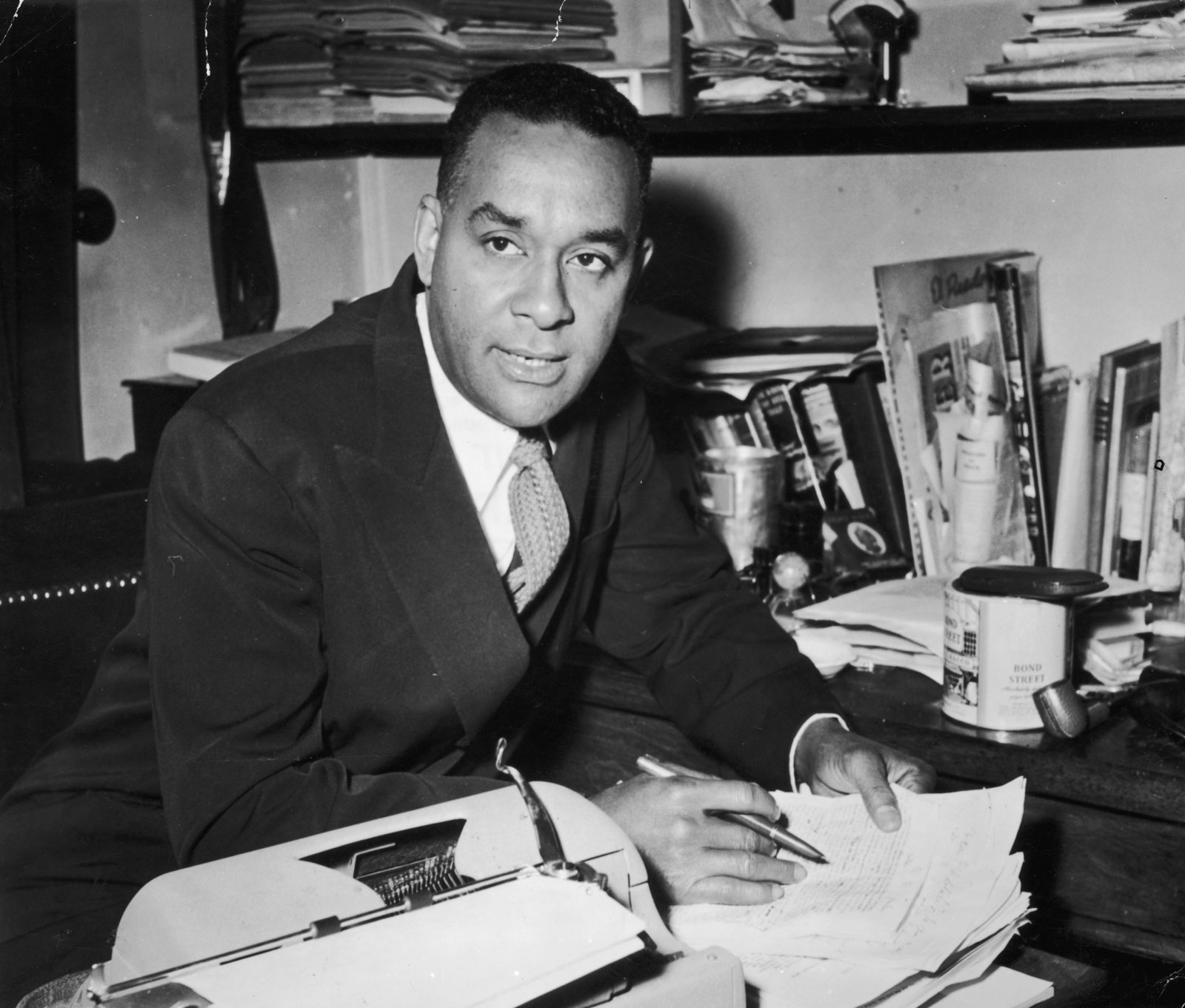

Bedridden in his Odéon apartment, Richard Wright—author of the 1940 novel Native Son and the autobiographical Black Boy (1945), his searing account of growing up in the Jim Crow South—spent the last year and a half of his life, before his death in 1960 at the age of fifty-two, writing haiku: “The sound of the rain / Blotted out now and then / By a sticky cough.” Wright had moved his family to France in 1946 to avoid the suffocating racism of the United States and the harassment of the FBI, which investigated his past ties to Communists, his advocacy of civil rights, and his criticism of imperialist American foreign policy during the cold war. “So far as the Americans are concerned,” he wrote, at the height of his haiku period, “I’m worse than a Communist, for my work falls like a shadow across their policy in Asia and Africa.”

A South African friend had given Wright, who was suffering from a severe case of amoebic dysentery probably picked up in Ghana, a book of Japanese haiku in R.H. Blyth’s translation, little suspecting the torrent of poems that the gift would unleash. Julia Wright recalled how her father “would hang pages and pages of them up, as if to dry, on long metal rods strung across the narrow office area of his tiny sunless studio in Paris, like the abstract still-life photographs he used to compose and develop himself at the beginning of his Paris exile.” Wright feverishly wrote some 4,000 haiku, from which he selected 817 as worthy of publication. (Housed at Yale’s Beinecke Library, they remained unpublished until 1998.) Julia Wright chose one of the poems, a metaphorical self-portrait, as Wright’s epitaph: “Burning out its time, / And timing its own burning, / One lonely candle.”

Those sheets of haiku hanging in Wright’s studio recall the career of the Japanese poet Masaoka Shiki (1867–1902), the greatest of all modern haiku masters, and a major influence on Wright. It was Shiki who, during the 1890s, revived haiku (a word he invented, to replace the older hokku) in response to the cultural pressures of Westernization. “When Shiki began his work,” Donald Keene notes in The Winter Sun Shines In: A Life of Masaoka Shiki (2013), “there was only a wandering interest in haiku and not one poet who is still remembered.” Shiki had studied English, admired Abraham Lincoln for his self-sacrifice to his principles, and loved to play baseball. But Shiki was also a passionate scholar and practitioner of traditional Japanese and Chinese poetic forms. He shrewdly countered Anglo-American modernism—with its emphasis on the spare, the fragmentary, and the suggestive (and, in Ezra Pound’s case a decade later, an Orientalist interest in Confucianism and the Chinese written character)—by promoting a Japanese alternative steeped in tradition but laced with contemporary experience. “As it spills over / In the autumn breeze, how red it looks— / My tooth powder!”

Like Wright, Shiki was bedridden when he wrote his best-known haiku, suffering for the last seven years of his life—he died in 1902 at the age of thirty-four—from excruciating tuberculosis of the spine. “Unable to sit or stand,” Keene notes, “he wrote his manuscripts on sheets of paper pinned above his bed.” Shiki took his pen name from the cuckoo, whose song is said to resemble the sound of someone coughing up blood. Many of his late poems invoke illness, like his so-called “farewell to the world,” a tradition among haiku poets: “The sponge gourd has flowered: / here lies a man dead, / suffocated by phlegm.” The poem invokes the loofah plant, grown for medicinal purposes; harvested before flowering, its juice was believed to thin mucus and ease coughing.

Shiki’s poetry also inspired Jack Kerouac, who began writing haiku around the same time that Wright did. “The greatest haiku of them all probably is the one that goes ‘The sparrow hops along the veranda, with wet feet.’ By Shiki,” says Japhy Ryder (modeled on Gary Snyder) in Kerouac’s Dharma Bums (1958). “You see the wet footprints like a vision in your mind and yet in those few words you also see all the rain that’s been falling that day and almost smell the wet pine needles.”

Advertisement

Both Wright and Kerouac were drawn to haiku as an art of improvisation. “How about making them up real fast as you go along, spontaneously?” Japhy Ryder suggests. While Wright’s haiku rarely invoke racial identity, and even when they do, only indirectly (“In the falling snow / A laughing boy holds out his palms / Until they are white.”), they engage African-American culture by evoking jazz: “From a tenement, / The blue jazz of a trumpet / Weaving autumn mists.” The way Wright played with the conventions of haiku—honoring the seventeen-syllable pattern and evoking its traditional seasonal themes while giving both a contemporary twist—can be likened to a jazz musician’s adapting a “standard” (a Broadway showtune, a spiritual, a classical melody) and finding fresh ways to give it new life, often with a dash of humor. “With a twitching nose / A dog reads a telegram / On a wet tree trunk.”

Wright’s haiku can also be thought of as a late contribution to Imagism. “No ideas but in things,” wrote the poet William Carlos Williams, calling for a new kind of poetry that would banish Romantic self-involvement and Victorian verbosity. A pediatrician by profession, Williams explicitly linked his Imagist practice to the flu pandemic of 1918. In the first poem of his epochal Spring and All (1923), he wrote: “By the road to the contagious hospital / under the surge of the blue / mottled clouds driven from the / northeast—a cold wind.” It is as though the threat of contagion has sharpened the poet’s vision, italicized it, so to speak, with a steel-edged acuity resembling haiku.

We have all experienced the ways in which the Covid-19 pandemic has shortened our attention spans, drained our energy, and made us fearful of the future. For Richard Wright and Masaoka Shiki, lying on their sickroom beds, writing haiku was an art of short spurts of insight followed by exhaustion. “I believe his haiku were self-developed antidotes against illness,” Julia Wright wrote of her father, “and that breaking down words into syllables matched the shortness of his breath.” On the morning before Shiki died, his sister held up a drawing board so that he could write his final poems. She said nothing as he paused after each line, choking on phlegm. When he had finished, according to Keene, “he let the brush drop, apparently exhausted by the effort.”

“Each event spoke with a cryptic tongue,” Wright wrote, in a lyrical passage from Black Boy. “And the moments of living slowly revealed their coded meanings.” With Whitmanian expansiveness, he wrote of the “echoes of nostalgia I heard in the crying strings of wild geese winging south against a bleak, autumn sky.” In the tighter confines of Japanese haiku, and the isolation of his Paris apartment, Wright found a more surgical way to register how moments might speak with a cryptic tongue. “As day tumbles down, / The setting sun’s signature / Is written in red.”