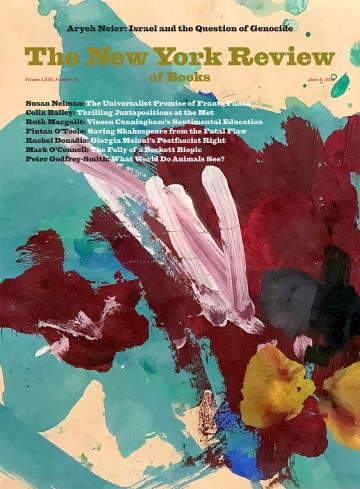

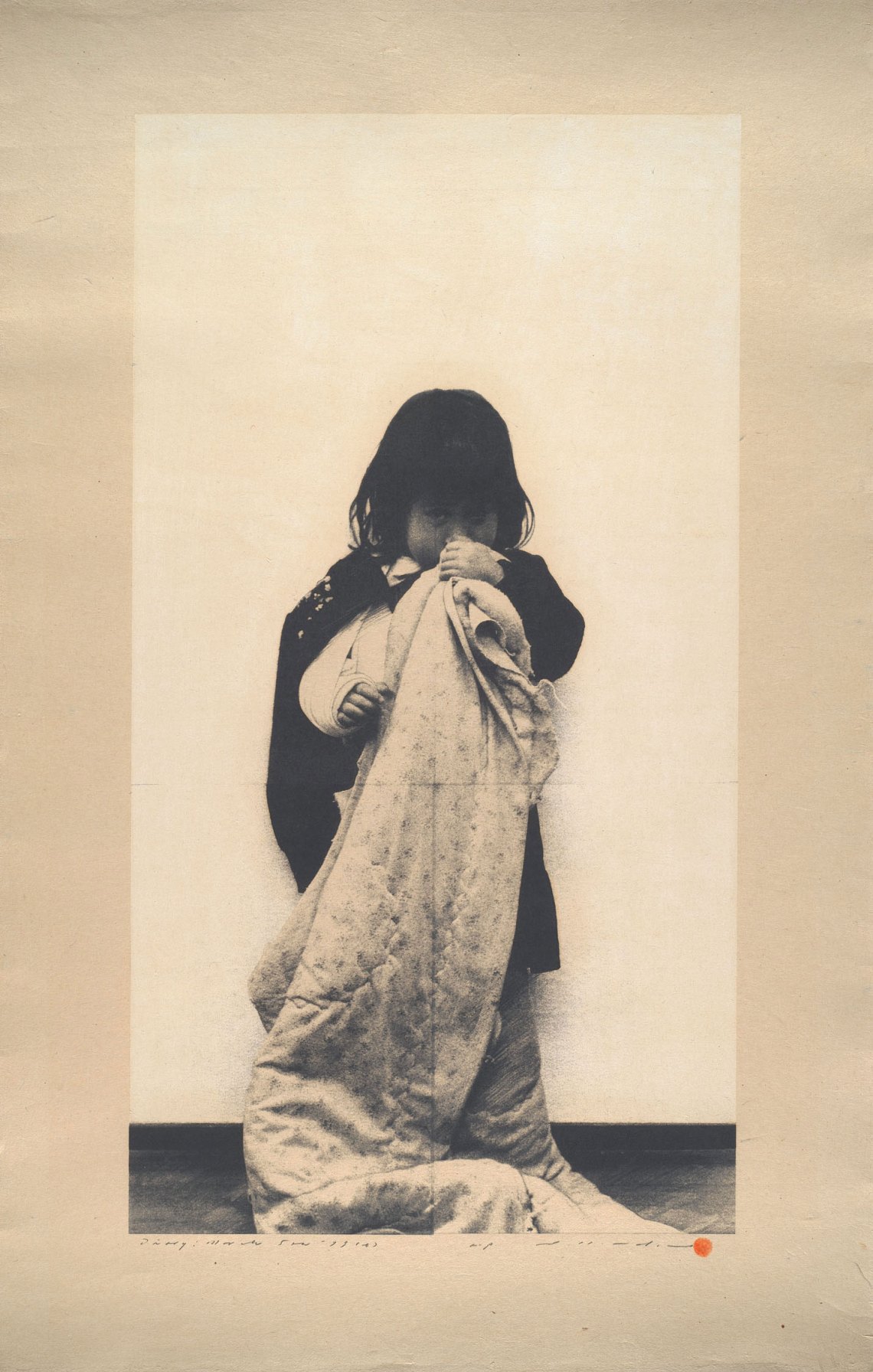

One day in 1973, the Japanese artist Tetsuya Noda asked his Israeli wife, Dorit Bartur, to pose with him for a family portrait to document their son Izaya’s first birthday. The photograph he made became the basis for one of the silkscreen prints included in “Noda Tetsuya: My Life in Print,” an exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago that opened on February 29 and was on view for only two weeks before the museum had to close. In this mostly monochrome print, Diary: Oct. 25th ’73, husband and wife perch on green floor-cushions in front of fusuma sliding doors, wearing Western clothes. Their son, his outfit a pop of fluorescent yellow, pokes out from behind his mother’s back. The room’s walls and tatami floor have been edited out, so that the family appears to float in the middle of the frame.

Noda is one of Japan’s foremost print artists, with works in the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art, the British Museum, and Tokyo’s National Museum of Modern Art. Born in 1940, he began keeping illustrated diaries as a young boy, drawing and writing about growing up in the small town of Uki, on Kyushu, the southernmost of Japan’s main islands. He later studied oil painting at Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music, and earned degrees in 1963 and 1965, but he was uninspired by much of the coursework, which focused on Western techniques and concepts. Spurred by a friend’s discovery that mimeograph machines, largely consigned to secretarial tasks, could be used to turn photographs into stencils for printmaking, Noda returned to his childhood practice of making art about his life. For more than fifty years now, he has devoted himself to a single series: Diary.

The show at the Art Institute, curated by Janice Katz, brought together twenty-seven works from Diary. Noda’s source materials are snapshots of his everyday life—his wife and two children, gifts from friends, produce from his garden. Using a pencil, whiteout, and other assorted tools, he retouches the photographs, removing extraneous elements and blurring lines in a process he calls “cooking.” Next, using a mimeograph machine, he converts this altered image into a silkscreen stencil. He then adds color with woodblocks, a traditional Japanese printmaking method. This idiosyncratic combination of techniques makes for an unconventional marriage of East and West.

In the lower right-hand corner of each of his prints, alongside his signature, Noda stamps his thumbprint in the bright red hanko ink traditionally used for personal seals. This stamp is a guarantee of the work’s authenticity, but not necessarily of the truth of its subject matter. Noda isn’t interested in documenting what happened or telling a story that coheres over time. Instead, his Diary is a testimony to the way our perceptions and memories are constantly evolving. He revisits the same subjects—red apples, overflowing ashtrays, his children’s toothy grins—but trains his eye on different details each time. Even the most familiar motifs of daily life retain a sense of mystery.

Noda made his first print using this method in 1966. Shortly before then, while working as a teaching assistant at his alma mater, a student had introduced him to Dorit, the daughter of Israel’s then-ambassador to Japan. By 1968, they were engaged. Noda made a pair of family portraits to commemorate the occasion. In each, a set of parents sits on a vividly colored sofa against a plain white backdrop, surrounded by their children. The Noda clan sits upright, dressed in formal attire; the Barturs’ posture and dress are more relaxed. Each print is annotated with the name, date of birth, and sex of each family member, floating in boxes over them. Side by side, they show the unlikely meeting of two families and cultures. The diptych earned Noda the International Grand Prize at the Tokyo International Print Biennale at the age of twenty-eight.

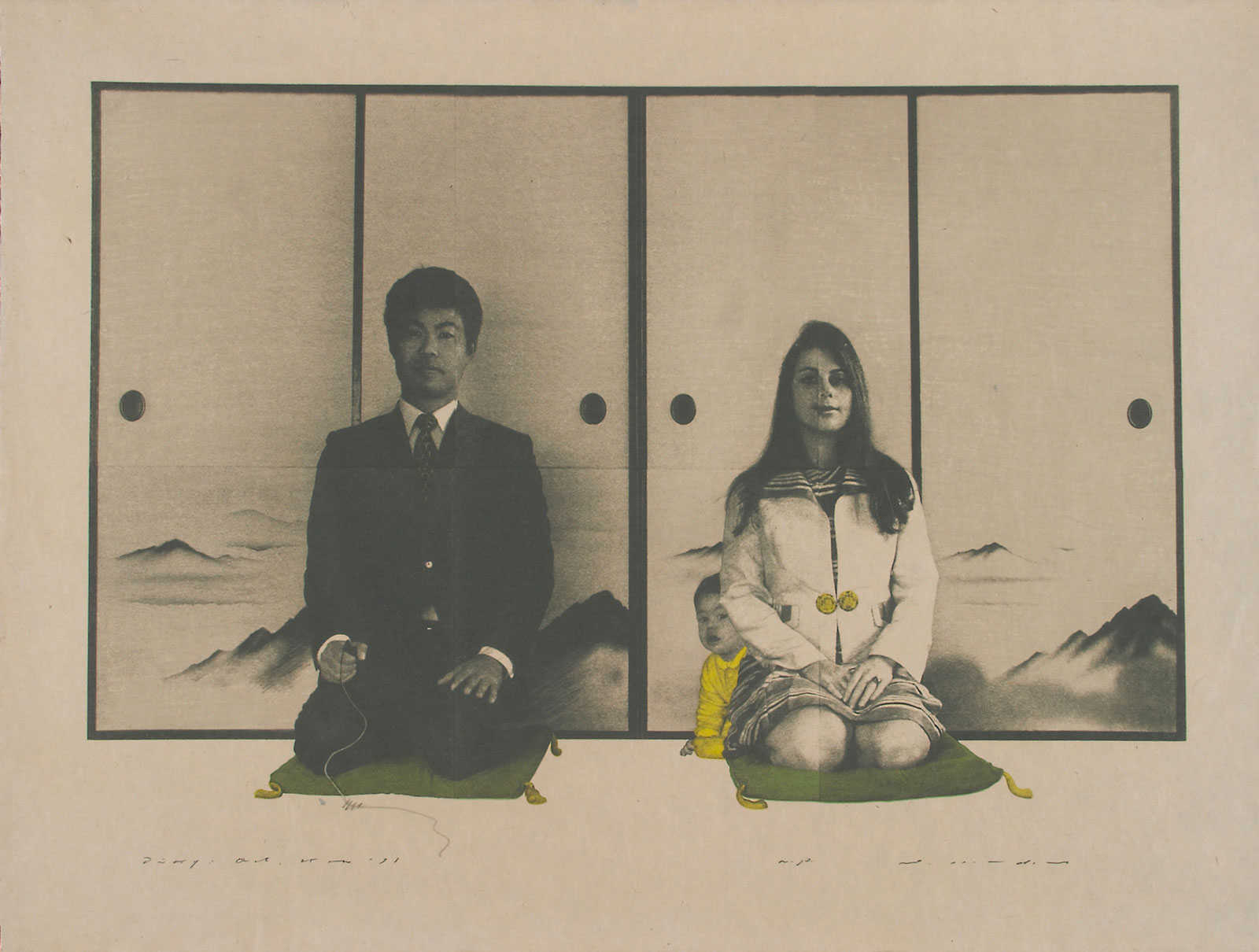

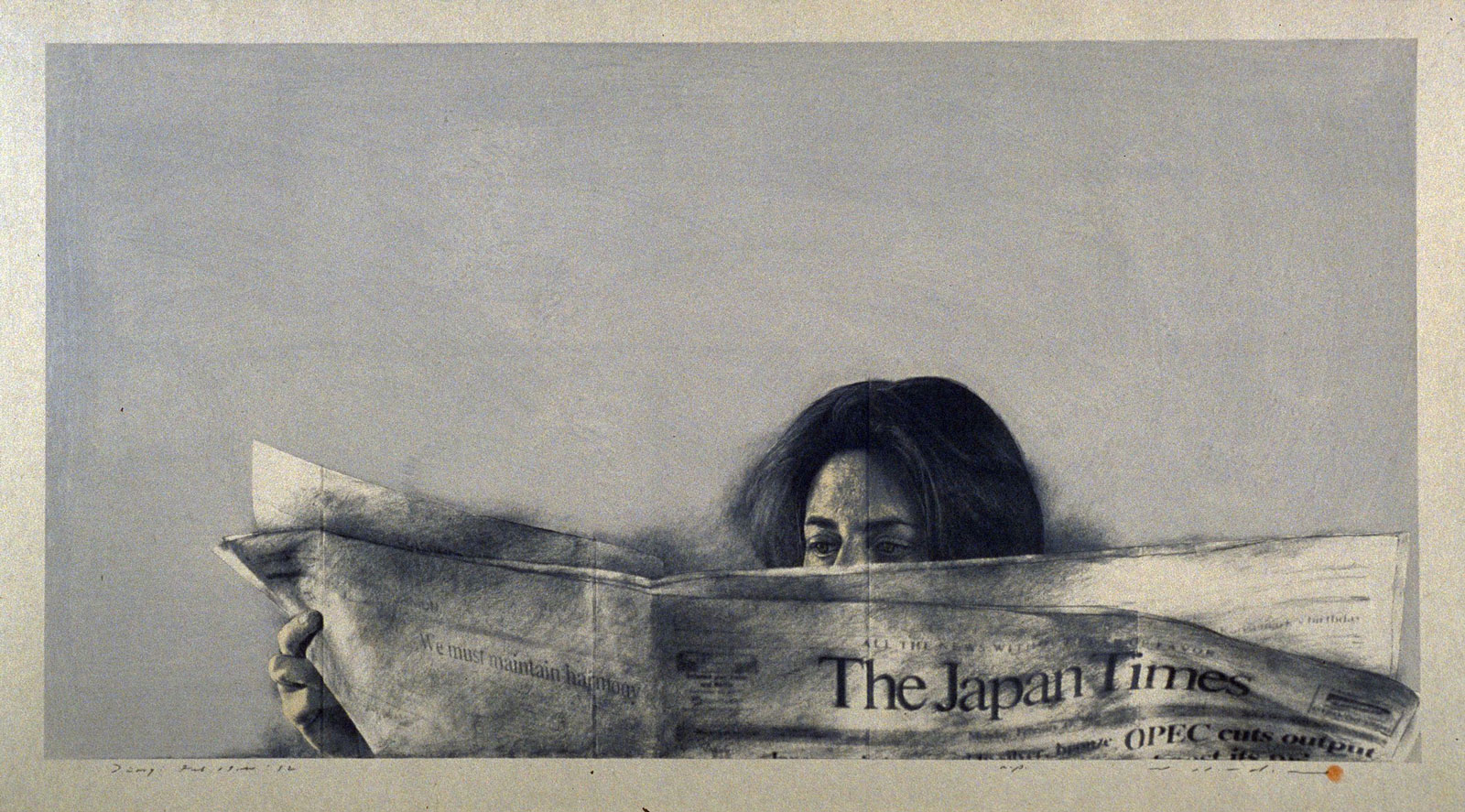

Many moments from Noda’s early adulthood were included in the exhibition: his first visit to America, his marriage to Dorit and conversion to Judaism, the childhoods of their son and daughter. Developments in his artistic style and his personal life seem to orbit one another. Monochrome images of his daughter, Rika, clutching her baby blanket or crying at the dinner table exemplify the style of his work during the late 1970s and early 1980s, when his children were young. In these heavily saturated black-and-white prints, the background has been edited away, but his children are rendered with photographic precision. It is as though Noda wanted to remember these moments exactly as they played out.

Advertisement

In another print, Diary: June 23, 1971—based on a photo from his wedding—Noda experiments with trilingual text, typing and pasting the words “Our wedding ceremony was held at 4:15 in the afternoon June 23rd, 1971 at the Israel Embassy garden in Tokyo” onto the image in English, Hebrew, and Japanese. It’s an early example of the way that translation and movement between cultures are central to his work and life. The exhibition also included works depicting Noda’s reactions to major world events. One, from the day after the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011, is a twist on a traditional still life: bottled water, canned fruit, and a Rembrandt catalog are carefully placed in front of scenes from a TV news report.

Sometimes, Noda’s work has the vividness of photojournalism. Elsewhere, it can be hard to tell if his prints were ever photographs at all. One work at the far end of the gallery, Diary: July 11th, ’97, which shows Dorit and a grown-up Rika, looks almost hand-drawn. Noda’s careful pencil work rims their heads with graphite halos, leaving them hazy and dreamlike. As I stood in front of it at the Art Institute, I overheard the woman next to me murmur, “God, I wonder what they’re thinking about.”

Noda’s prints seem to encourage this kind of puzzling. His use of negative space is an artistic choice that nods to tradition. Ma, the Japanese concept of the space left between things, can be seen in historic screens, scrolls, and even the layout of Shinto shrines.

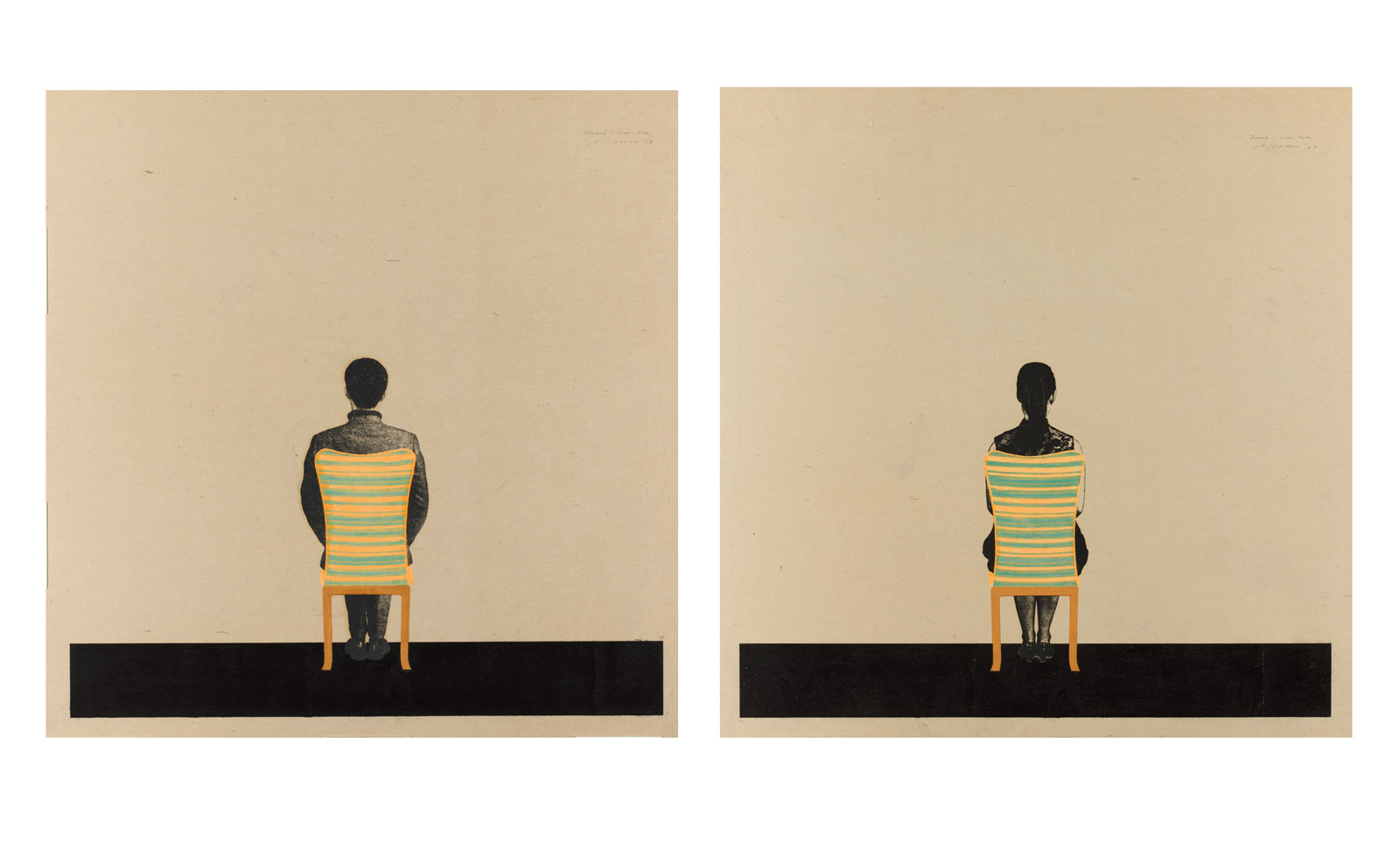

Most of the works on display were accompanied by wall text that included short reflections from Noda on when he took the initial photograph for a given print, or why he made this or that creative choice. The exhibit’s final two works, Diary: Nov. 7th, ’68 #1 and #2, show Dorit and Tetsuya each seated alone in the same colorful, striped chair, alongside the following text:

These are a pair of prints of my fiancée, Dorit Bartur, and me seen from the back. Why did I choose not to show us from the front? I felt this would be too obvious or ostentatious, and besides, I am shy or a bit self-conscious. Also, these images show a realistic setting and I wanted to express them in a more abstract or mysterious way.

In a case at the other end of the gallery, four small, three-dimensional works were on display. These objects are a little-known part of Noda’s oeuvre. One, titled Diary: Today, is made up of a pair of thirteen-centimeter-wide acrylic plates bolted together to form a box with a miniature empty yellow chair—an unambiguous symbol of the West to anyone who grew up sitting on tatami mat floors—printed on the front. Made in 1969, it’s one of the only works in Noda’s Diary that does not include a date in the title. “I titled this work Diary: Today because the acrylic plate around the chair is translucent,” the accompanying text reads. “The people and objects seen through it can change every day, creating a new image.”

“Noda Tetsuya: My Life in Print” opened on February 29 at the Art Institute of Chicago, now closed temporarily due to the Covid-19 pandemic.