At a press conference in Tokyo in July 1966, a Japanese jazz critic asked John Coltrane what he would like to be in ten years. “I would like to be a saint,” he replied. Coltrane, who died the following July of liver cancer, at forty, reportedly laughed when he said this; but among his followers, he was already considered a spiritual leader, even a prophet. His reputation rested not merely on his musicianship, but on the example he set, the self-renunciation and good works required of every saint. Unlike the alto saxophonist Charlie Parker, who launched the bebop revolution with the trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, Coltrane was not a fully formed virtuoso when he first emerged, but rather a committed and tireless student of the horn—a hardworking man who arrived at his sound through a practice regime of almost excruciating discipline. “He practiced like a man with no talent,” his friend the tenor saxophonist Benny Golson remembered. The saxophonist Archie Shepp, one of Coltrane’s many protégés, exaggerated only slightly when he remarked that he never saw him take the sax from his mouth. The trumpeter Miles Davis, in whose mid-Fifties quintet Coltrane first rose to prominence, made the same observation, though more in exasperation than worship.

Early in his career, Coltrane had succumbed to the temptations of the jazz life, but by 1957 he had kicked the habits of both needle and bottle, devoting himself to his music, and to God. The religion he embraced was ecumenical: an eclectic mixture of Christianity, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Sufi Islam—“I believe in all religions,” he said. Self-effacing and humble, he paid generous tribute to his influences—Lester Young, Ben Webster, Dexter Gordon, Sonny Rollins, John Gilmore—and helped younger musicians land contracts with his own label, Impulse Records. Coltrane, whose command of the tenor was unmatched (except, perhaps, by Rollins), even took lessons with free jazz artists like Ornette Coleman and Albert Ayler, whom other musicians of his stature derided as charlatans, adapting their innovations to his purposes. In his lifestyle, Coltrane stood apart for his indifference to the scene. While Miles Davis socialized with Harry Belafonte and Marlon Brando at uptown galas, and the pianist Cecil Taylor and Coleman mingled with bohemian painters and poets on the Lower East Side, Coltrane lived with his family in the middle-class suburb of Dix Hills, Long Island, and kept to himself. He projected selfless dedication, purpose, and—as the alto saxophonist Darius Jones recently put it to me—“service.”

Service—or, more precisely, spiritual commitment—was the ethos that permeated much of Coltrane’s music and, above all, his devotional suite A Love Supreme, recorded in December 1964 at the New Jersey studio of Rudy Van Gelder with his classic quartet—McCoy Tyner on piano, Elvin Jones on drums, and Jimmy Garrison on bass. A Love Supreme was at once the culmination of Coltrane’s modal period and an announcement of his decision to pursue music as a quest for spiritual enlightenment. He composed the score in September 1964, shortly after the birth of his first son, John Jr., and only a few months after the death of his close friend Eric Dolphy, who had accompanied him on alto saxophone, bass clarinet, and flute on some of his finest sessions in the early Sixties. According to John’s widow, the pianist Alice Coltrane, he locked himself in a room for five days, and then, “like Moses coming down from the mountain,” declared that he had “received all the music” for A Love Supreme. Bob Thiele, his producer, was not happy about Coltrane’s desire to record a long-form original composition, but this somber and austere thirty-three-minute suite in four movements became the most popular record of his career, surpassing his 1960 cover of the Rodgers and Hammerstein song “My Favorite Things.”

“My Favorite Things” became Coltrane’s signature song: he played it countless times in concert, sometimes for as long as an hour. In his liner notes to an especially thrilling performance in Austria, My Favorite Things Graz 1962, released last year on Hat Hut, the jazz critic Art Lange observes that the tune became “an ironic metaphor of his dependency and freedom—to be revered, reexamed, revamped, but never ignored.” By contrast, Coltrane appeared hesitant to toy with A Love Supreme, as though his offering to God should remain intact, an inviolable record of his epiphany, if not a holy object in its own right.

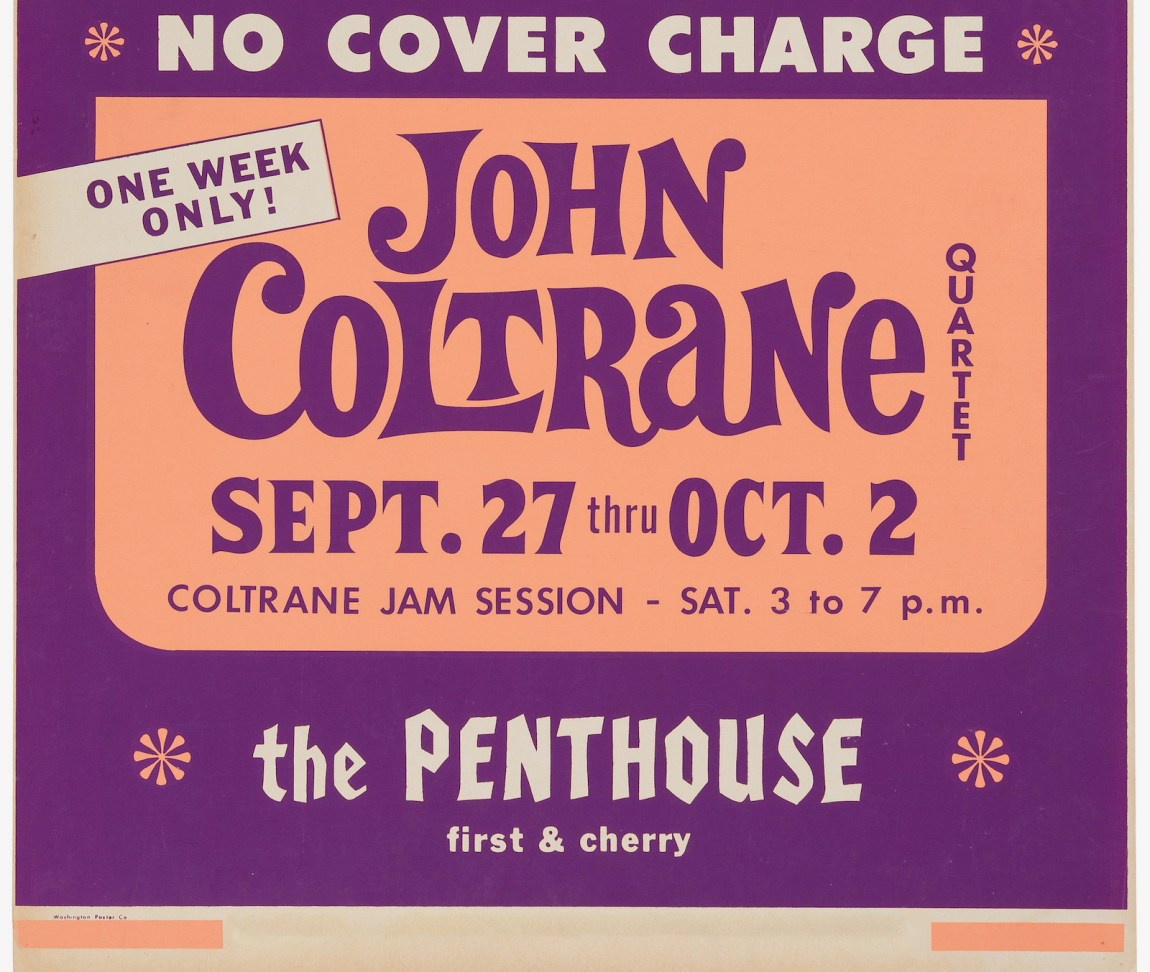

As far as most of us knew, there was only one live recording of A Love Supreme, a forty-seven-minute version performed on July 27, 1965, at the Antibes Jazz Festival at Juan-les-Pins, France, in which Coltrane’s playing is exquisite yet somewhat restrained. But in 2013, a Seattle-based saxophonist named Steve Griggs discovered another live recording of A Love Supreme that had been taped by Coltrane’s friend, the saxophonist and flutist Joe Brazil, on October 2, 1965, at the end of a week’s engagement at the Penthouse, a Seattle club. More than twice as long as the studio recording, A Love Supreme: Live in Seattle is nothing short of a revelation: a bracing reimagining of the original, revealing the ways in which Coltrane’s understanding of his masterwork had evolved—and the radical new direction in which his music was moving.

Advertisement

*

The studio recording of A Love Supreme begins with the stroke of a Chinese gong, followed by a fanfare featuring Coltrane’s tenor in E major. The opening theme, “Acknowledgment,” a four-note motif in F minor played first by Garrison on bass, is so distinctive that it is now as anthemic as the beginning of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. (According to Coltrane’s son Ravi, a superb tenor and soprano saxophonist himself, he based this motif and others like it on the “ratios known as the Golden mean, also called the divine proportion”: an example, he believes, of “the deep symbolism in his compositions, a code that reached beyond the music itself.”) Coltrane plays it in every key during his improvisation; he also overdubbed himself chanting “a love supreme,” one syllable per note, a full nineteen times, over the rhythm section. The concluding section, “Psalm,” is an instrumental recitation, intended to echo, syllable for syllable, a poem that Coltrane wrote in praise of God, as the Coltrane biographer Lewis Porter has shown. The two middle movements, “Resolution” and “Pursuance,” are more conventional in their exploration of blues and swing, but they also conjure the wailing, non-Western tonalities that Coltrane wanted to incorporate in his music.

To listen to A Love Supreme in a single sitting is to experience a sense of searching and striving: a journey toward transcendence in the face of imposing obstacles, a process of overcoming that is depicted by Coltrane’s horn. He achieves this exalted effect with a saxophone sound stripped bare of artifice, using hardly any vibrato; his tone is hard, unsentimental, sometimes piercing, and—in the triumphal reprise of the fanfare at the end—soaring. The music is propelled forward, imbued with its inexorable force, by Elvin Jones’s relentless, thrashing polyrhythms, McCoy Tyner’s open fourths, and Jimmy Garrison’s faultlessly singing tone: a sonic architecture of exacting, almost divine symmetry. Like only a few other devotional works—Bach’s St. Matthew Passion, Olivier Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time, Mahalia Jackson singingDuke Ellington’s “Come Sunday”—A Love Supreme has the power, it seems to me, to turn the most hardened atheist into an agnostic, if not a believer. With this composition, Coltrane moved decisively into a realm toward which, in retrospect, all of his previous work with the quartet had pointed: an improvisatory spiritual music, rooted in blues and jazz, yet whose “world-weary melancholy and transcendental yearning…recall Bach more than [Charlie] Parker,” as the critic Edward Strickland wrote. Today, the studio recording of A Love Supreme can be heard every Sunday at the African Orthodox Church in San Francisco, which in 1982 officially canonized “Saint John William Coltrane.”

In their performance of A Love Supreme in Seattle, the quartet were were joined by Pharoah Sanders, a tenor saxophonist from Arkansas whom Coltrane had met in San Francisco, Coltrane’s old friend from Chicago, Donald (Rafael) Garrett, who played bass, and the Panamanian alto player Carlos Ward. The sound quality could be better—Coltrane’s tenor is frustratingly muffled—but the music (all seventy-eight minutes of it) is astonishingly good. The approach to the music feels brighter and more joyous than the studio version: this is an ecstatic, collective celebration of God’s powers, rather than an individual’s introspective profession of faith. The band’s performance is also much wilder than in the Antibes performance: Tyner’s playing is so percussive that he sometimes sounds like Cecil Taylor; Sanders’s growls prefigure his vocalized sounds on “The Father and the Son and the Holy Ghost,” the opening section of Coltrane’s Meditations, recorded that November. Yet there are also softer passages of arresting beauty, such as the extended duet between Garrison on pizzicato and Garrett on arco, and Coltrane’s stately prayer in the closing “Psalm.” Elvin Jones (who is very high in the mix) is riveting throughout, and most of the musicians double up on small percussion instruments (bells, clave sticks, gourds, a scraper), creating an inviting quilt of ethnic rhythms. This was an effect that both the Art Ensemble of Chicago and Miles Davis would, in different ways, try to replicate in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Unlike other recent albums of previously unreleased Coltrane material, such as the fine but inessential Both Directions at Once: The Lost Album (2018) and Blue World (2019), A Love Supreme: Live in Seattle is a genuine event, an expansive reconfiguration of his most significant work.

Advertisement

As innovative as the Seattle recording was, it was not the first time Coltrane had performed the music with a larger ensemble. The day after laying down the original studio version of A Love Supreme, he went back in with his quartet and two other musicians: the tenor saxophonist Archie Shepp and the bassist Art Davis. Shepp, by his own admission, felt intimidated about accompanying his hero, and responded to Coltrane’s statement of the theme with incongruously funky lines. Although Coltrane shelved the tracks they recorded, he thanked Shepp and Davis in his liner notes, adding that he hoped “we will be able to further the work that was started here.” He never let go of the idea of playing the music with a bigger group, and by the time he arrived in Seattle, he was heading rapidly toward a looser approach that favored collective improvisation.

1965 was the year Coltrane officially joined the ranks of the free jazz movement, which had already claimed him as its leader. The moment was as pivotal as 1957, the year he quit heroin and dedicated himself to God. In March, he took part in “New Black Music,” a group concert organized by the poet and jazz critic Amiri Baraka as a benefit for his Black Arts Repertory Theatre/School in Harlem.(In his liner notes to the recording of the benefit, The New Wave in Jazz, Baraka hailed Coltrane as “a mature swan whose wingspan was a whole new world. But he also showed us how to murder the popular song. To do away with weak Western forms…. When he speaks of God, you realize it is an Eastern God. Allah, perhaps.”) Three months later, Coltrane recorded Ascension, a nearly forty-minute group improvisation for the quartet, joined by Art Davis on bass, Shepp and Sanders on tenor, Marion Brown and John Tchicai on alto, Freddie Hubbard and Dewey Johnson on trumpet. As Brown put it, “you could use this recording to heat up the apartment on cold winter days.” With its daunting degrees of density and cacophony, Ascension sounds, at times, like a jazz version of primal scream therapy—or, perhaps more charitably, a recasting of New Orleans jazz polyphony. Whether or not you liked Ascension, you couldn’t deny Coltrane’s courage: the era’s most successful saxophonist had made one of the most anticommercial albums in music history. As the composer George Russell put it, “That’s when Coltrane turned his back on the money.” Coltrane himself conceded that he was “a little worried it may puzzle people. And sometimes I deliberately delay things for this reason. But after a while I find that there is nothing else I can do but go ahead.”

Ascension was widely interpreted as Coltrane’s response to Ornette Coleman’s collective improvisation for a double quartet, Free Jazz, released four years earlier. Coltrane was an admirer of Coleman’s work, and on the 1960 album The Avant-Garde had recorded his tunes with Coleman’s sidemen Don Cherry, Charlie Haden, and Ed Blackwell. But, in Ascension and all the music that followed—“late Coltrane,” as it’s known—Coltrane wasn’t following anyone’s muse other than his own. As with everything he’d done so far, he arrived at “free jazz” through patient, contemplative study, and interminable practice. (As the pianist Craig Taborn recently pointed out to me, Ascension, which is based on a five-note motif similar to the theme of A Love Supreme, sounds much more like an organic extension of Coltrane’s previous work than Free Jazz does of Ornette Coleman’s earlier recordings.)

Coltrane wasn’t seeking an escape from chord changes, which he’d already found in modal jazz; nor was he drawn to Coleman’s Whitmanesque exaltation of individual voices, the idea at the heart of what Coleman would later call “harmolodics.” Ever since the early 1960s, when Coltrane began to experiment with modes, drones, and repetition, he had been trying to generate a form of trance, a state of oneness. As Ekkehard Jost writes in his 1974 study Free Jazz, “the individual usually has only a secondary importance” in Ascension, subsumed by “orchestral sound structures.” Coltrane’s late music is incredibly raw, yet curiously impersonal—as if it contained the sigh of the world, not his own. It’s also terribly serious, even earnest, compared to the playfulness of Coleman or the circus humor of Ayler. Reflecting on Coltrane’s music in his 1968 book Black Music, Baraka wrote that “the message of the New Black Music is this: find the self, then kill it.” Coltrane did not want to “kill” anything, but, as Baraka understood, Coltrane aspired to a form of collective expression in which the soloist would achieve a higher unity with other instrumental voices, as one brick in a much larger wall of sound. To call his late music “free jazz” is to overlook its central impulse: not emancipation from authority, but devotion and surrender to a higher authority. Coltrane, who recorded a composition titled “Selflessness” in 1965, was a rare ascetic in a movement of aesthetic libertinism.

*

When Coltrane embarked on his religious journey in 1957, he said that he hadn’t so much discovered as rediscovered God. Born on September 23, 1926, in Hamlet, North Carolina, he grew up in a deeply religious home. His father, John Robert, was a tailor and amateur violinist; his mother, Alice, dreamed of becoming an opera singer. Shortly after their son’s birth, the couple moved to the town of High Point, where his maternal grandfather, Reverend William Wilson Blair, gave fiery sermons in the African Methodist Church, denouncing the evils of the white man with a bluntness that electrified some of his congregants and worried others. (He was Coltrane’s first model of a righteous, plainspoken performer whose passions made him fearless.) On December 11, 1938, Reverend Blair died of lobar pneumonia; three weeks later, Coltrane’s father also died, probably of stomach cancer. According to Lewis Porter, he turned to clarinet and alto saxophone after his father’s death, “as if practicing would bring his father back.”

In 1943, Coltrane moved to Philadelphia, where his mother had settled a year earlier with his older cousin, Mary, who helped raise him. (Years later, he titled one of his best-known tunes “Cousin Mary.”) He took saxophone and theory lessons with Leo Ornstein, a Ukrainian immigrant who ran a school on Spruce Street. And in 1945, he heard Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, which, he said, “knocked me to my knees.” After military service, spending two years playing in Navy marching and dance bands, Coltrane returned to Philadelphia and began his extended apprenticeship in groups led by Jimmy Heath, Johnny Hodges, Earl Bostic, and Gillespie. He also played in popular rhythm and blues bands whose horn players were expected to “walk the bar,” soloing on their instruments while walking through the audience. (Coltrane apparently declined, finding this practice undignified.) The leader of one of those R&B groups was the altoist and singer Eddie “Cleanhead” Vinson, who first had him switch to tenor. After the engagement, Coltrane was set to return to the alto, but he had a dream in which Charlie Parker discouraged him from doing so—Coltrane always respected the visions he received.

While Coltrane’s early bandstand education could scarcely have been improved upon, his most important studies took place in his mother’s Philadelphia apartment, where he practiced his instrument until he fell asleep. His first influence on tenor was Lester Young, because, as he told an interviewer, “I could feel that line, that simplicity.” But he soon became enamored of Coleman Hawkins’s use of arpeggiated chords, and Dexter Gordon’s phrasing. Coltrane was not a quick study but a thorough one: he learned everything there was to know about his instrument, and developed equal strength in all its registers.

In 1955, Coltrane landed a job in Miles Davis’s first great quintet. In Davis’s band, he would develop what Ira Gitler called his “sheets of sound”—arpeggios and scales played so fast they resembled chords. The garrulous intensity of Coltrane’s playing perfectly offset the leader’s spareness, but critics urged Davis to fire the young saxophonist: his sound was harsh, unpretty, and dour, they complained; Nat Hentoff, later one of Coltrane’s great champions, accused him of a “general lack of individuality.” Davis knew better, and kept him—until 1957, when he did fire Coltrane for turning up to work drunk.

Coltrane then joined Thelonious Monk’s band, further refining his sound on a series of Monk albums, and during the band’s residency at the Five Spot Café in New York. With the help of his first wife, Naima, a devout Muslim, he also quit heroin and alcohol, experiencing the spiritual revelation that, he wrote in the liner notes to A Love Supreme, “was to lead me a richer, fuller, more productive life.” His playing not only grew more consistent and self-assured; it achieved a new kind of lyricism, unadorned, naked, and probing. When Monk’s producer Orrin Keepnews heard Coltrane’s solo on the ballad “Monk’s Mood,” he was so moved that he apologized to Coltrane for failing to “get to know you or hear you earlier than this.” “No,” Coltrane replied, “I wish I had known myself earlier.”

Having exorcised his demons, Coltrane established himself as the most influential tenor of his era, combining technical prowess with an unusually frank expressiveness, as if he had eliminated the fourth wall between musician and listener. He released a series of classic hard-bop albums (Blue Train and Soultrane both in 1958, Giant Steps in 1960) that demonstrated his gifts both as an improviser and as a composer. (Tunes like “Moment’s Notice,” “Lazy Bird,” “Spiral,” and “Giant Steps,” among others, are now standards, as well as staples of jazz school education.) And in 1959, he briefly returned to the Davis band, performing on Kind of Blue, in which the trumpeter turned away from the harmonic complexities of bop in favor of a simpler, more open-ended approach based on modes. Coltrane immediately grasped the potential of modal music, especially the flexibility that it afforded him as an improviser. While he had made a name for himself writing harmonically demanding tunes like “Giant Steps,” he had been looking to express himself more directly, more plainly, especially in ballads like “Naima,” a gorgeous melody over pedal tones, dedicated to his wife. It was Coltrane, even more than Davis, who turned modal jazz into a veritable movement in the early 1960s. His first major hit, a hypnotic fourteen-minute version of “My Favorite Things” in which he performed entirely on soprano saxophone, transformed a waltz from The Sound of Music into an enigmatic, dark-hued enchantment, suffused with the sonorities of the Karnatic music he’d been studying in his spare time. Baraka praised Coltrane for being the first to “break out of the Tin Pan Alley penitentiary,” but he did so in part by drawing upon a Tin Pan Alley song, revealing dimensions its composers had scarcely fathomed.

On “My Favorite Things,” Coltrane was accompanied by McCoy Tyner, a pianist he’d met in Philadelphia in 1955, Elvin Jones, a drummer from Detroit, and the bassist Steve Davis. (The “classic quartet” formed when Garrison joined the group at the end of 1961.) Tyner, whose Muslim name was Suleiman Saud, had developed a comping style based on ringing left-hand rhythmic chords; Jones, in Coltrane’s words, “had the ability to be in three places at the same time.” In these two men, Coltrane found the ideal partners to move his music in a less Western direction, by relying on vamps, polyrhythms, subtle repetition—and drones, about which he had another of his premonitions. He had been listening closely to field recordings of West African percussion, and he wanted to recreate their timbral range, their rhythmic depth and invention. In the spring of 1961, he recorded Africa/Brass, with Tyner and Jones, Reggie Workman and Art Davis on bass, and an eighteen-piece orchestra of saxophones, trombones, French horn, tuba, and euphonium. The title track, a sixteen-minute Coltrane composition based on a double-bass drone in E and arranged by Eric Dolphy, features one of his most commanding, sinewy improvisations, aiming to evoke the African bush and the rebirth of an ancient continent just then coming into independence. But it confounded critics by utterly breaking with the expectations of harmonic development that jazz shared with most Western music. The jazz critic Martin Williams said he could not hear “anything more than a dazzling and passionate array of scales and arpeggios…an extended cadenza to a piece that never gets played.”

It was for this very reason that a group of young classical composers, later known as Minimalists, found “My Favorite Things” and “Africa” so exhilarating. In fact, Coltrane acted as a bridge between the West Coast school of La Monte Young and Terry Riley and the East Coast school of Steve Reich and Philip Glass. “The giant in all this harmonic stasis for me was John Coltrane in his Africa/Brass album of 1961 where the title tune is sixteen minutes—all on E!” Reich told The Independent newspaper. “The constant harmony just highlighted the melodic invention, rhythmic complexity, and timbral variety. Sound like a lesson for my piece Drumming?” Glass, noting that Coltrane had reintroduced the soprano saxophone to jazz, and that he had brought three of them into his own ensemble, mischievously remarked to an interviewer: “Where do you think I heard that sound?” For his part, Riley—a soprano saxophonist himself—has said that Coltrane’s music taught him how to “work with chord clusters in different parts of the tetrachord,” and how to sustain musical interest “in a kind of stasis,” something he later learned was a major technique in Indian music.

The Minimalists’ curiosity about the harmonically static, rhythmically intricate music of the Global South—specifically of India, West Africa, and Indonesia—was first sparked by their encounter with Coltrane. The titles of his new pieces (“India,” “Olé,” “Tunji,” “Liberia,” “Brasilia,” “Ogunde”) indicated the geographical breadth of his listening, but to his credit, Coltrane never attempted to reproduce, or vulgarize, the sound of these musical traditions. He was not interested in pastiche, but rather in “the presence of the same pentatonic sonority…. It’s this universal aspect of music that interests me and attracts me.” Coltrane also listened to Bartok and Shostakovich, and based his 1961 composition “Impressions” on a motif from Ravel’s “Pavane pour une infante défunte.” But he never studied classical music—other than, he noted, “the type that I’m trying to play.” His music remained black American to the core, even as it soaked up other influences, a tribute to the enormously absorptive capacities of the blues tradition.

From late 1961 until 1965, Coltrane and his quartet enjoyed one of the most enthralling runs in twentieth-century music. Some of their work was “fire music,” preacherly modal jazz, drawing its energy from Jones’s immensely powerful drumming. In its great live albums recorded at the Vanguard and Birdland, the quartet pushed jazz to the edge of atonality, especially during Coltrane’s feverish duets with Jones. But Coltrane also recorded more subdued, traditional albums of disarming tenderness, notably Ballads and his sessions with Duke Ellington and the singer Johnny Hartman. His most beautiful work of all, Crescent, was a record of original ballads, rich in Afro-Latin grooves and singable melodies, completed six months before A Love Supreme. Perhaps the most outstanding quality of the Coltrane quartet was its uncompromising honesty. Although Coltrane’s technique had never been more staggering in its achievement, he placed little value on virtuosity as an end in itself, having come to view music as “an expression of higher ideals, of brotherhood.” He wanted, he said, to be “a force for real good. I know that there are bad forces, forces that bring suffering and misery to the world, but I want to be the opposite force.”

Coltrane’s humanistic ideals did not protect his music, or him, from displays of hostility. After one performance, a Southern white man came up to him and said, “Mr. Coltrane, I don’t like your music. It sounds like n— hate music to me.” Coltrane’s critics may have avoided racist invective, but he was no less hurt by the charge they leveled against him: that his music was “angry.” As he told Hentoff, “the only one I’m angry at is myself when I don’t make what I’m trying to play.” (If he appeared always grave, even severe, in photographs, the reason he seldom smiled for the camera is that he was embarrassed about his bad teeth.) In 1961, John Tynan, the editor of DownBeat, accused Coltrane of leading a “growing anti-jazz trend,” of “deliberately destroying jazz” with his “nihilistic exercises.” With Coltrane, the British poet and jazz enthusiast Philip Larkin fumed, jazz “started to be ugly on purpose.” These attacks became increasingly furious as Coltrane grew closer to the avant-garde, which anointed him, rather than Ornette Coleman, Albert Ayler, or Cecil Taylor, as their spiritual leader. As the critic Gary Giddins remarks in the new documentary Fire Music, the reason the jazz establishment was so troubled by his embrace of the avant-garde was that “you couldn’t say that Coltrane can’t play.”

With his customary humility, Coltrane responded to his critics in Downbeat by suggesting that they meet, the better to understand one another’s work. “With this understanding, there’s no telling what could be accomplished.” They either ignored or rejected his offer—one critic, Don DeMicheal, answered by sending him a copy of Aaron Copland’s Music and Imagination. In a letter written in June 1962, Coltrane thanked DeMicheal, but said that he did not “feel that all of his tenets are entirely essential or applicable to the ‘jazz’ musician,” who did not suffer from alienation from the audience, or from a lack of “justification for his art”:

We have absolutely no reason to worry about lack of positive and affirmative philosophy. It’s built in us. The phrasing, the sound of the music attest to this fact. We are naturally endowed with it. You can believe all of us would have perished long ago if this were not so. As to community, the whole face of the globe is our community. You see, it is really easy for us to create. We are born with this feeling that just comes out no matter what conditions exist. Otherwise, how could our founding fathers have produced this music in the first place when they surely found themselves (as many of us do today) existing in hostile communities where there was everything to fear and damn few to trust.

Jazz innovators belonged to a global community much larger than white America, he went on, and if they “met with some degree of condemnation,” so had Van Gogh, a “man who found himself so much at odds with the world he lived in” yet continued to express “that wonderful and persistent force—the creative urge.”

Among black musicians and writers, Coltrane had less need to explain why he didn’t try to sound smooth like Stan Getz, or why he played little of the standard repertoire. People who grew up in the black church had a better understanding of what Nathaniel Mackey, one of many black poets who have made careful study of Coltrane’s work, calls the “recursive quandary” of his music, its incantatory, even obsessional nature, reflecting Coltrane’s understanding of music as “gnostic announcement, ancient rhyme.” He had begun drifting toward ritualistic forms of musical expression (West African percussion, Ravi Shankar’s sitar) and toward prayer and chanting, experiences of worship that he tried to convey in songs like “Spiritual,” and later in A Love Supreme, “Dear Lord,” and “Dearly Beloved.” The growls, shrieks, screams, and other extended sounds that mystified many of Coltrane’s critics could be traced back to the church; for some, they alluded to the challenges confronting the black freedom struggle. As the poet Sonia Sanchez wrote, “my favorite thing/is u/blowen/yo/favorite things. Stretchen the mind/till it bursts past the con/fines of solo/en melodies/to the many/solos/of the mind/spirit.” Sanchez relished the idea that what she loved in Coltrane’s music would be “TORTURE” to whites who “TORTURED US WITH PROMISES.”

But if the music was torturing anyone, it was Coltrane himself, who would sometimes solo for an hour at a time in concert, playing for long stretches in extreme registers. “When you play the horn, there’s a comfortable level where you’re breathing and using the muscles you train to play it,” the composer and saxophonist Darius Jones said. “Coltrane is literally pushing beyond his physical capability and trying to stay in that zone. He’s trying to exist in that place of being on the edge, and to control it. That’s really hard physically, because you might break.” The purpose was as much metaphysical as physical: for Coltrane, the beauty of music lay in the struggle to overcome his own physical and emotional limits and express the unsayable. Determined to find the “one essential” note, he was fully prepared to fail in search of it. (Unlike his teachers Davis and Monk, who used pauses and silence to brilliant effect, Coltrane left virtually no negative space in his playing.) By constantly risking failure—and by making this struggle the drama of each of his improvisations—he created some of the most powerful art of the twentieth century.

By the early 1960s, Coltrane had come to be seen as a black revolutionary leader—an embodiment, in Baraka’s words, of the “same life development” as Malcolm X. Coltrane’s status was all the more striking given that Max Roach, Charles Mingus, and Sonny Rollins each recorded works of militant protest music, while Coltrane steered clear of political discussion (except where the reception of his music was concerned), and spoke in a language of peace and compassion, almost never referring explicitly to civil rights or race. When the Marxist jazz critic Frank Kofsky grilled him about his views on Vietnam War and Black Power, Coltrane said that he was “quite impressed” by a Malcolm X speech he’d attended, and that he opposed all wars; but he was obviously uncomfortable under such questioning. He and his second wife, Alice, a musician from Detroit whom he met in 1963 and who had joined him on his spiritual journey, were private people who recoiled from publicity. (Perhaps significantly, she had the same first name as his mother.)

Yet, more than any of his peers, Coltrane gave intense, wordless expression to the strivings and sorrows of his people, in pieces like “Africa,” “Spiritual,” and, above all, “Alabama,” his lacerating elegy for the four girls killed in the September 15, 1963 bombing at the 16th Street Church in Birmingham. Other jazz protest pieces were surrounded by ennobling rhetoric, by the noise of insurgent titles (“We Insist,” “Freedom Now Suite,” “Fables of Faubus”); Coltrane said little about “Alabama,” his Guernica, except that “it represents, musically, something that I saw down there translated into music from inside me.” He composed it after reading Martin Luther King Jr.’s speech after the bombing, and he used King’s cadences as a basis for the piece, which the quartet recorded in Van Gelder’s studio in November. In the space of five minutes, in sections delineated by a rare and theatrical pause, “Alabama” moves between anguished dirge and furious blues, an anticipation in miniature of A Love Supreme. For all the restlessness of Coltrane’s music, he had a rare ability to capture the stillness and solemnity of reflection, on pieces such as “Alabama,” “Naima,” and “Psalm,” perhaps because it was so hard won. Improvisational turbulence and an unending search for salvation and serenity formed the dialectic of what Shepp called Coltrane’s “world religious music.”

Religious man though he was, Coltrane never ceased to wrestle with self-doubt. “I haven’t quite found out how I want to play music,” he told the critic Leonard Feather. “Most of what’s happened in the past few years has been questions. Someday we’ll find the answers.” In the last two years of his life, his music evolved radically under the force of those questions. In 1965 alone, Coltrane recorded more than ten new albums, including the late masterpieces Transition, First Meditations (a dry run for the quartet), and Sun Ship, none of which was released in his lifetime. “This is when Coltrane’s sound starts to become transcendental and to float above everything else,” the composer George Lewis reflected in a recent conversation. “His vibrato is like Korean traditional music, and it’s incredibly affecting. It gives me goosebumps just to talk about it.”

In its late September series at the Seattle Penthouse, the Coltrane quartet, joined by Pharoah Sanders and Donald Garrett, gave startling new shape to standards like “Body and Soul” and “Out of this World,” turning them into brooding, spectral reflections of his earlier renditions. (These performances were released in 1971 on a double album also titled Live in Seattle but not including the final night’s performance of A Love Supreme.) On October 1, the day before the performance of A Love Supreme, the musicians went into the studio with the flutist Joe Brazil to make Om, which Coltrane intended as an evocation of “the first vibration—that sound, that spirit, which set everything else into being. It is The Word from which all men and everything else comes, including all possible sounds that man can make vocally. It is the first syllable, the primal word, the word of power.” A frenzied, often forbidding work, reportedly performed under the influence of LSD, Om begins and ends with the group chanting a verse from the Bhagavad Gita, which Coltrane had brought to Seattle. The performance of A Love Supreme is infused with the abrasive energy of that record, but it remains poised on the edge of the volcano. While this version anticipates Coltrane’s dialogues with Sanders on the late masterpiece Meditations, it also looks back to the roiling orchestrations of Africa/Brass (another work for two basses), while Ward’s alto playing evokes the fractured cries of Eric Dolphy, Coltrane’s beloved sideman on early Sixties albums like Olé and Live at the Village Vanguard.

A few months later, the quartet broke up. Elvin Jones didn’t like having to share with the young reed players Coltrane was mentoring (“Oh, no, here comes another one of those motherfuckers,” he would say to himself), but he could handle that. The ultimate indignity came when Rashied Ali, a young firebrand from Philadelphia who used to mock Jones from the audience, joined the group as a second drummer on Meditations. Jones quit, followed by Tyner, who said that all he could hear was noise. In 1966, Coltrane formed a new quintet with Garrison, Ali, Sanders, and Alice Coltrane, who played in a more impressionistic style than Tyner, producing washes of color over which her husband could improvise. She was nervous at first, playing with only a few octaves, but “he told me to play the whole piano, utilize the range so I wouldn’t be locked in. It freed me.” The work Coltrane created in his final year is some of the most radical of the era, thanks in large part to Ali’s “multidirectional rhythms,” as Coltrane described them, a swirling pulse in which fixed time signatures and meter have been abolished. Yet the music is more structured, much less “free,” than critics understood at the time: Coltrane’s gnarled, spiraling, compulsive style remained as fierce and focused as ever. And in ceremonial ballads like “Peace on Earth,” which he performed in Japan after praying at the memorial for the dead in Nagasaki, Coltrane delivered some of his most lyrical, wrenching solos. Other than the filmmaker Ingmar Bergman—who also came from a family of pastors and grappled relentlessly with spiritual questions—no artist of the era captured the vulnerability and anguish of the human condition with such visceral force.

But Coltrane was a dying man, and for that reason his late work could also be unbearably painful to listen to, suggesting, in Edward Strickland’s memorable phrase, “a suffering man’s breath.” During his November 1966 concert at Temple University, where he played before an audience of white hipsters and Black Power activists, Coltrane took the horn out of his mouth and began beating on his chest, screaming into the microphone. “People really thought he’d lost his mind then,” Rashied Ali remembered. “He wasn’t even playing anything recognizable to them with the horn.” Coltrane had always possessed, in Cecil Taylor’s words, a “feeling for the hysteria of the times,” but he no longer transcended it. In the spring of 1967—weeks after recording his final masterpiece, an album of duets with Ali, Interstellar Space—he was diagnosed with cancer; on July 17, he died.

“I regret Coltrane’s death as I regret the death of any man,” Philip Larkin wrote, “but I can’t conceal the fact that it leaves in jazz a vast, blessed silence.” Meanwhile, in Newark, New Jersey, Amiri Baraka was whistling “all I knew of Trane” to maintain his spirits in prison, where he’d been placed in solitary confinement during the city’s uprising, when a guard came by to tell him that his “man Coltrane” was dead. Baraka was shattered by the news, but after his release he listened to Meditations, and“it told me what to do/Live, you crazy mother/fucker!/& organize yr shit/as rightly/burning!” Until his death, in 2014, Baraka continued to spread Coltrane’s gospel; the rhythm and sound of his poetry were transformed by his encounter with the saxophonist’s music, which expressed “our own search and travails, our own reaching for new definition. Trane was our flag.” Among black poets in the 1970s, the “Coltrane poem” became a genre unto itself. As A.B. Spellman remarked in his 1973 poem “Did John’s Music Kill Him?”, “trane’s horn had words in it.”

What those words meant was another matter, and Coltrane himself had provided little explicit guidance. In the 1960s and 1970s, Baraka and his comrades in the Black Arts Movement had looked to Coltrane as a leader, hearing a rousing call to self-organization and revolution in his music. But in an interview with the radio host Christopher Lydon recorded a year before his death, Baraka stressed the music’s universal emotional force, praising Coltrane for “opening up…the depth of our feelings, because most of us live on the surface of our feelings.” Just how difficult this intensity of feeling was to achieve was underlined by the proliferation of Coltrane imitators, most of whom were content to surf on modal grooves, saxophone shrieks, and ritual intonations of “a love supreme.” Arguably, Coltrane kitsch did inspire some lasting work: Pharoah Sanders, one of Coltrane’s legitimate musical “sons,” famously adapted the bass riff from “Acknowledgment” in his epic groove piece “The Creator Has a Master Plan,” featuring the yodeling of Leon Thomas, in a gloss on Coltrane’s spare chants on A Love Supreme. But there were all too many saxophonists who copied Coltrane’s playing with as much devotion as he had given to the Lord, leaving even Coltrane’s admirers longing for Larkin’s “vast, blessed silence.”

Not surprisingly, one of the most affecting tributes came from his widow, who would later become a spiritual leader in her own right, serving as the guru of an ashram she founded in Los Angeles. On her 1971 album Journey in Satchidananda, Alice Coltrane created a loving portrait of her late husband based on themes he’d written, with Sanders on soprano and Ali on drums, and a percussionist called Tulsi playing a drone on the tamboura, an Indian lute Coltrane had tried out in his 1961 concerts at the Village Vanguard. The music offers to transport us back to Coltrane’s sound world, with its familiar modal feeling, and Alice plays fourth chords reminiscent of her predecessor, McCoy Tyner. Yet the title, “Something About John Coltrane,” suggests that this is not merely a portrait, but a widow’s act of mourning, a remembrance of something ineffable and elusive about John Coltrane that defies comprehension, a rare flash of the spirit in our fallen world.