I heard about war for the first time when I was around four and we were still living in Brooklyn. My mother and I were going down in the elevator with Paula, a neighbor there in Bay Ridge whom my mother found “annoying” because her brassy hair wasn’t a real color and she used to ring our doorbell to collect money for various causes. I remember that Paula was wearing purple from head to foot. “I hope we do get into a war,” she said to my mother. “I think it will serve us right.” “Serve you right” were words any child in those days understood perfectly. I wondered what “we” had done, for which “we” were going to be taught a lesson.

After that, I kept hearing the word “war” on the radio, but I didn’t pay much attention to it. By the fall of 1941, I was intent on learning to read. It came very easily to me, since it was what I most longed to do. My mother, in her misguided attempts to raise a prodigy, kept me away from other kids and didn’t like me to have playmates, but soon I’d be able to lose myself in a storybook whenever I needed to, without waiting for a grown-up to read to me. I gobbled up each new word I was taught and made it mine, and could easily reel off all the various members of what my first-grade teacher called “word families,” with their endings of “ing” and “at.” I loved the calm, predictable routines of school and the prizes I was awarded for my progress—little squares of yellow paper with gold stars or stamped-on pictures of rabbits or baby chicks, which I kept at home in a special box. But one day, my reading lesson was interrupted.

It was Monday, December 8. No one had told me about the bombing of Pearl Harbor, which had happened just the day before.

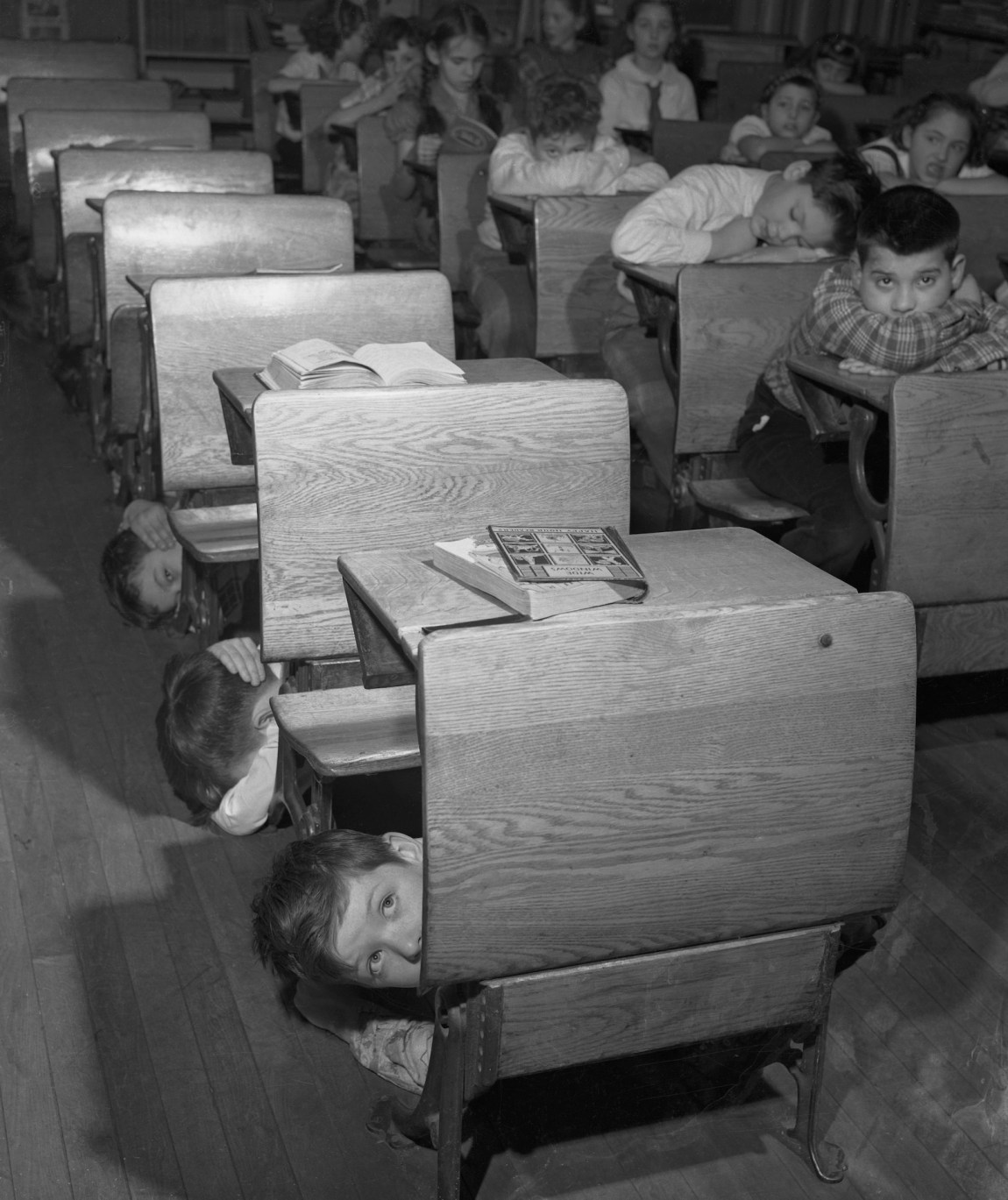

When my mother took me to school that morning, parents and teachers were talking tensely to one another in the hallways. Only a little while after I sat down at my desk and the reading lesson started, a bell rang, and our teacher told us we were going to have an air raid drill. In case we had to suddenly run from the building, she told us to gather up our coats and galoshes, books, and pencil cases before we followed her downstairs to the basement. There, we first graders stood waiting with all the older kids for an endless stretch of time, until we heard another bell and were allowed back in our classroom.

Air raid drills became a feature of every school day. You never knew when the bell would ring, and you’d have to drop everything and take shelter. I hated this new, disrupting feature of school. The basement of the building was enormous and confusing. If you got separated from your class as everyone hurried down the stairs, you would have to wander around forlornly carrying all your stuff until, at last, you found the sign with your group’s special color and number. I didn’t really grasp that we might all be in danger.

Our teacher handed out elastic bracelets with little dangling celluloid discs on which each child’s name and birth date were neatly printed. She told us we had to wear these on our wrists at all times, so that we could be “identified” if necessary. She didn’t explain what “identified” meant. Very soon, my bracelet fell off somewhere. This presented me with one of the first serious dilemmas of my life. Which would be worse, I wondered: not being identified or telling our teacher I’d lost my bracelet? Telling her would be worse, I decided.

For the next four years of my childhood, The War—which I thought of respectfully in capital letters—was the offstage accompaniment to my largely peaceful daily life. Although the air raid drills continued, and blackout blinds were lowered in windows each night, and radio announcers said London was being bombed, and little boys ran around the schoolyard with outspread arms tilting from side to side and yelling ack-ack-ack at one another, enemy planes never flew over Bay Ridge—or over Manhattan, where we moved by the time I was nine—or anywhere else in the country. Since neither my father nor my uncles had been drafted, and I had been assured that President Roosevelt would take good care of us and keep The War from coming to America, I felt no real fear of it, although I knew that Hitler hated Jews like me and my family.

Advertisement

What do I actually remember about The War? The blue stamps in ration books, shortages of sugar and butter, my mother stitching up the runs in her pink rayon stockings, the indignant reminder “It’s a free country” (now no longer in currency) that kids resorted to when other kids tried to boss them around. I remember a darkened Times Square thrillingly crowded with soldiers and sailors on leave, neighborhood drives to collect big patriotic balls of saved-up tinfoil and rubber bands, and the grave, pervasive drone of the radio that I heard at home morning and evening. But I hardly listened, burying myself in the books I’d brought home from the library until I was sent to bed and my mother turned off the light.

At ten, the haze of childhood lifted, and I became more conscious of the world at large. That April, there was the shock of President Roosevelt’s death, followed by his black-draped portraits that immediately appeared everywhere, even in our corner grocery store. Then came August with the news of America’s great atomic secret weapon and the two huge bombs President Truman had dropped to end the fighting. Not long afterward, I saw disturbing footage of what remained of Hiroshima—a flat plain of rubble with one scorched, standing tree—in a newsreel that preceded the main feature at the Nemo Theater, a few blocks from our new Upper West Side apartment. On the same screen, I also saw twisted, naked skeletal corpses piled up in the yard of a concentration camp. “Cover your eyes,” my mother whispered, too late. Four years later, I would sign the Stockholm petition against nuclear weapons that someone was circulating in Washington Square.

At Hunter, my high school, the drills I’d grown accustomed to continued long past the end of The War. All four hundred girls would file into the auditorium and get down on the floor in front of the folded-up seats that were supposed to protect us from the new types of bomb that could obliterate everything in a second. Mrs. Root, the music teacher, would wait for us to settle down before stepping onto the stage to lead us in “Jingle Bells” or “My Old Kentucky Home” or blithe rounds of “Row, Row, Row Your Boat.” We all knew how ridiculous this was. “Life is but a dream,” we’d sing in bored voices, rolling our eyes at one another.

In 1950, during my last year at Hunter, there was one glorious outbreak of resistance. A small group of students, who had arranged to crouch in the same row, overwhelmed Mrs. Root the moment she appeared before us by bursting into “Orange Colored Sky,” a song I heard that day for the first time. Ostensibly about the explosive impact of love, its intent may have been subversive, for in its lyrics glass shattered and the ceiling fell, even the ground caved in. We Hunter girls were well-behaved—in training to become mature adult members of the Silent Generation—but who could resist the liberating opportunity to sing “I’ve been hit! I’ve been hit!!” or to belt out the onomatopoeic refrain “Flash, Bang, Alakazam!” Within moments, the song ignited the voices of even the timid girls, as our teachers ran around frantically trying to quell our temporary seizure of the truth. “AlakaZAM!” I sang, with a giddy joy I was amazed to feel all over again, seventy years later, when I heard the song for only the second time on an old recording by Nat King Cole that I found online.

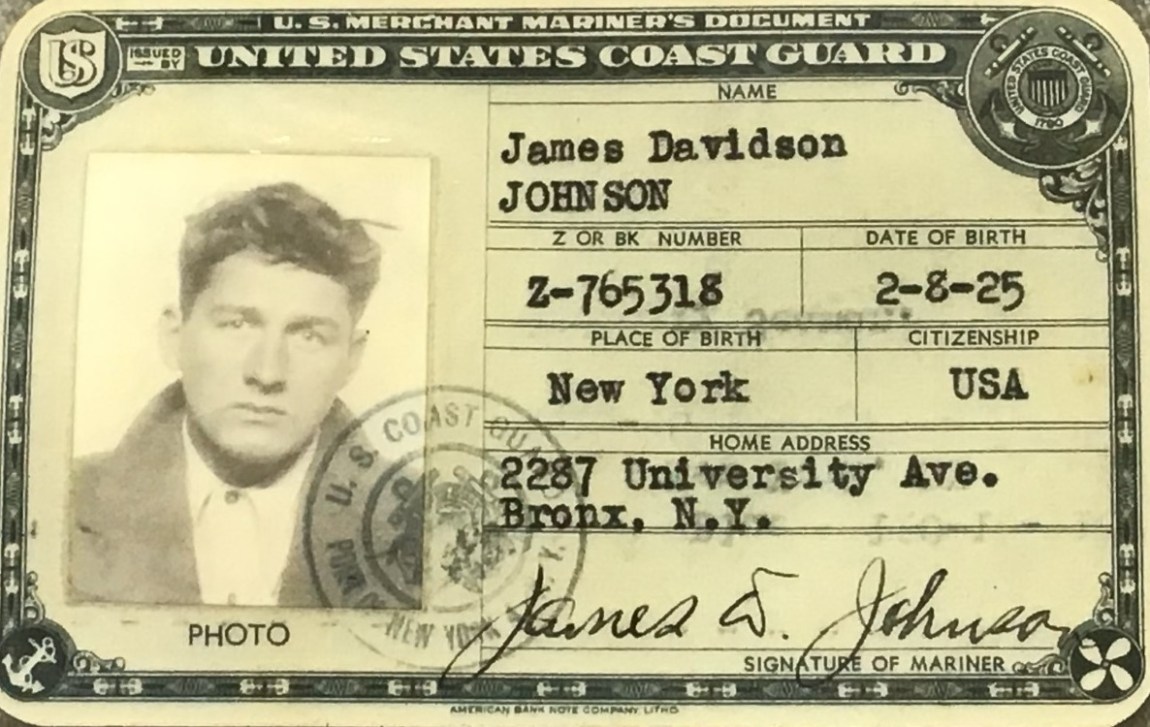

But The War didn’t really catch up with me until I was twenty-six. That was the year I went to a party and met James Johnson, a painter and war veteran, whom I married eight months later. Perhaps he’d been in one of those crowds of servicemen I’d seen in Times Square when I was a little girl. We’d speculate about that sometimes: the romantic possibility that two people fated to be together could have unknowingly walked right past each other.

Escaping from a home where he was regularly beaten by his stepfather, Jim had enlisted in the navy at seventeen, when I was in second grade, and had served on minesweepers off the coast of Italy. He’d participated in the landing at Anzio. Two of his ships had struck mines, and twice he’d been rescued from the sea. He’d seen other young men—his shipmates, his closest friends—fall dead all around him, which left him to wonder afterward why he was the one with nine lives. Death always seemed to be hovering around Jim’s thoughts, except perhaps when he was painting and nothing counted but the rain of reds, blacks, and grays on the white canvas. “It can all come down to where you happen to be standing at a given moment,” he would sometimes say, with an urgent incredulity in his voice, that would tell me he’d been pulled back to the exploding deck of a ship. “I’m talking about inches, you understand? Inches!”

Advertisement

He was still in his teens when he’d absorbed this acute awareness of mortality, and it gave him an intensity that I’d immediately found magnetic. But soon I learned how much he relied on alcohol to defend himself against his memories. Today, his diagnosis would probably be PTSD, though it was called battle fatigue back then. The men who’d fought in the Civil War must have come home from that carnage with something like it. Jim told me that the government had done a special study on the guys who’d served on minesweepers, and it had found an unusually high incidence of mental breakdowns, alcoholism, and suicides: “I want you to know, kiddo, that if anything happens to me, I’ll be eligible for an all-expenses-paid funeral.”

He was a man accustomed to taking risks—with the bold, wet strokes of each big new abstract painting he worked on (“This will either end up upon the wall or the floor,” he used to say), and with his life. He’d ride home to me on his red Harley-Davidson after a much too long afternoon at McSorley’s, the East 7th Street bar a little further uptown where women were not allowed inside to extract their men. The bike had a good deal of mileage. Jim had bought it from a painter who had given up on the art scene in New York and was returning to Texas. The engine had a rhythmic elderly cough that I learned to listen for on the nights I came home from work and didn’t find him there. If I kept a window open in our loft on Christie Street, I could hear It once Jim had rounded the corner of Grand Street and the Bowery. “Made it one more time,” he’d announce as he opened the door and swayed in.

I loved him more than I’d ever loved anyone before, and I tried to keep believing love would heal him. But with the arrival of the bike, I began to live in a growing state of dread.

Shortly before our first anniversary, Jim sat watching a TV special called “Victory at Sea,” as I stood at the stove making dinner. Suddenly, he called to me to come right away because he’d found himself looking at one of the minesweepers he’d served on. I didn’t move fast enough—maybe I didn’t want to. By the time I saw the screen, the ship was gone. I braced myself for the drinking that was bound to follow this destabilizing apparition, the terrible hours ahead—of waiting for him to make it home from East 7th Street on his Harley. This time, however, after we went through a few of our most harrowing days, Jim made me a promise that he was done with drinking.

A week later, he was killed when his motorcycle crashed into the back of a truck that happened to stop short on Bowery and Grand just as the light was changing. He would have come safely home if he’d had just a few seconds more to turn the corner. He lived long enough to tell the cops his name was James Johnson. “A painting isn’t finished,” he used to say, “until you’ve signed your name to it.” A couple of hours earlier, he’d called me at work, proud that although he had stopped in at McSorley’s, he was sober. He’d been absolutely right, of course, about how flimsy the dividing line can be between life and death. We need to ignore that in order to get on with living. While he was alive, I hadn’t wanted to know, or even hear, about that thing The War had taught him. But I haven’t ever forgotten it.