Of all the terrible sexual scandals the hierarchs in the Vatican find themselves tangled in, none is likely to do as much institutional damage as the astounding and still unfolding story of the Mexican priest Marcial Maciel. The crimes committed against children by other priests and bishops may provoke rage, but they also make one want to look away. With Father Maciel, on the other hand, one can hardly tear oneself from the ghastly drama as it unfolds, page by page, revelation by revelation, in the Mexican press.

Father Maciel, who was born in Mexico and died in 2008 at the age of eighty-seven, was known around the Catholic world. Against ordinarily insurmountable obstacles, he founded what was to become one of the most dynamic, profitable, and conservative religious orders of the 20th century, which today has 800 priests, and approximately seventy thousand religious worldwide. The Legion of Christ, nearly 70 years old as an order, is comparatively small, but it is influential: it operates fifteen universities, and some 140,000 students are enrolled in its schools (In New York, its members teach in eleven parish schools); and its leadership has long enjoyed remarkable access to the Vatican hierarchy.

A great achiever and close associate of John Paul II, Maciel was also a bigamist, pederast, dope fiend, and plagiarist. Maciel came from the fervently religious state of Michoacán in the southwest of Mexico, and grew up during the years of the Cristero war (1926–1929), a savage conflict that pitched traditional Catholics (Cristeros) in provincial Mexico against the anti-clerical government in the capital. One of his uncles was the commanding general of the Cristeros. Another four uncles were bishops. One of them, Rafael Guízar y Valencia, brought him into a clandestine seminary in Mexico City, where as a 21 year old who had not even taken his vows, Maciel created a new religious order that was intended to be both cosmopolitan and strict.

Given its founder’s age and general lack of education, it is not surprising that its aims were poorly defined, although in a fascinating study of Maciel by the historian and psychoanalyst Fernando M. González we learn that one of the order’s statutes specified that priests should be decenti sint conspectu, attractione corripiant, or graceful and attractive. At the age of 27 the young Father Maciel had an audience with Pope Pius XII, who, according to the Legionaries’ official history, urged him to use the order “to form and to win for Christ the leaders of Latin America and the world.” This has been the order’s unwavering mission for six decades, and with remarkable speed it emerged as a conservative force to rival even Opus Dei.

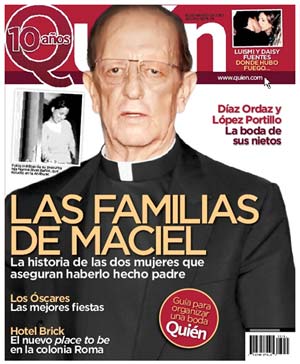

Maciel was evidently a man of some magnetism; dozens of wealthy women contributed generous amounts for the Legionaries’ good works, and the Mexican magazine Quién, normally known for its society pages and not for its investigative reporting, recently had a story about one of Mexico’s wealthiest widows, Flora Barragán de Garza, who donated upwards of fifty million dollars during the years of Maciel’s glory. “She gave him practically all our father’s fortune,” Barragán’s daughter told the Quién interviewer, adding that the family finally had to intervene so that the by then elderly woman would not be left destitute. Her generosity allowed Maciel to travel first-class throughout his peripatetic life, but it also provided the wherewithal for the network of private schools to which wealthy Mexican conservatives dispatched their children.

In 1997, a Mexican woman who was living in Cuernavaca looked at the cover of the magazine Contenido—a Reader’s Digest-y sort of publication—and saw on it the face of her common-law husband. She had been his partner for 21 years and borne him two children, and she knew him as a private detective or “CIA agent” who, for understandable work-related reasons, put in only occasional appearances at home. Now she learned that he was a priest and and that his real name was Marcial Maciel. He was, the magazine said, the head of an order whose strictness and extreme conservatism appeared to hide some vile secrets: the article, picking up information first brought to light in an article by Jason Berry in the Hartford Courant, revealed that nine men, one a founder of the Legionaries, another still an active member, and the rest all former members of the order, had informed their superiors in Rome that Maciel had abused them sexually when they were pubescent seminarians under his care.

The accusations were not new, nor would they be the last. In 1938 Maciel was expelled from his uncle Guízar’s seminary, and shortly afterward from a seminary in the United States. According to witnesses, Maciel and his uncle had a gigantic row behind closed doors, and one witness, a Legionary who had known Maciel since childhood, told the psychoanalyst González that the bishop’s rage had to do with the fact that Maciel was locking himself up in the boarding house where he was staying with some of the younger boys at his uncle’s seminary. Bishop Guízar died of a massive heart attack the following day.

Advertisement

Later, it would become known that Maciel had his students and seminarians procure Dolantin (morphine) for him. This led to Maciel’s suspension as head of the order in 1956. Inexplicably, he was reinstated after two years. Much later still, someone realized that his book, The Psalter of My Days, which was more or less required reading in Legionary institutions, and was a sort of Book of Hours, or prayer guide, was lifted virtually in its entirety from The Psalter of My Hours, an account written by a Spaniard who was sentenced to life in prison after the Spanish Civil War.

Uneducated and mendacious, Maciel nevertheless had a genius for politics, and for personal relations. According to a former Jesuit with good knowledge of the story, one of the very first sizable donations that the Polish Solidarity movement received came from Maciel, who raised the money among the conservative Mexican elite he had so steadfastly cultivated. No doubt the Polish Karol Wojtyla heard about this act of generosity and appreciated Maciel’s ideological stance. The priest was at John Paul’s side throughout the first three of the Pope’s five visits to Mexico: Legionary money, its priests, and its very active laypersons’ movement, the Regnum Christi, strengthened the Polish Pope’s campaign to remove socially radical or liberal priests from positions of power and give ascendancy to his conservative Catholicism.

It is hard not to think that these are the reasons the Vatican ignored the detailed and heartwrenching letter sent in 1998 by Maciel’s eight accusers (the ninth member of the group having died.) Even as the public first became aware of the accusations through the Hartford Courant and the Mexican press, which picked up the story immediately, the Vatican refused to act. Instead, Pope John Paul II put forward the beatification of Maciel’s mother and of his uncle, Bishop Guízar. (The bishop is now Saint Guízar. Maciel’s mother is still going through the beatification process.) It was only in 2006, after John Paul’s death, that a Vatican communique announced that Maciel had been “invited to lead a reserved life of prayer and penitence.” He lived out his final years quietly and died in the United States. The Legionaries, however, have continued to grow in numbers and in wealth.

It’s risky for a nonbeliever to try to evaluate how the Maciel narrative will affect the Church’s standing as a whole, because an outsider can understand so little of how a faith is lived among its rank and file. No doubt many Latin American believers know a parish priest who had a “housekeeper” and perhaps a “niece” living with him, because these things have never been uncommon here—or elsewhere, probably, although the effort to hide them may be greater. But Paraguayans have not abandoned their cheerful president, former priest Fernando Lugo, despite the fact that he is known to have fathered at least three children (he seems to think there may be more) while he was still a bishop.

Homosexuality has also been tolerated and to some degree almost expected of skirt-wearing priests in this macho part of the world. It is possible, perhaps, that for many Catholics baptism, confession, and weekly mass are almost bureaucratic procedures, like voting or getting a driver’s licence, and that true faith is something that happens at home-made altars and through the magical pathways of ritual, leaving priests to live their own lives as long as they do a creditable job with the sermons and the burials. The sexual abuse of children and its cover-up are a different matter entirely, one suspects.

As it turns out, Maciel’s common-law marriage to Blanca Estela Lara Gutiérrez was not exclusive. Some ten years after he met her, he began a long-lasting relationship with a 19-year old waitress from Acapulco, to whom he introduced himself as an “oil broker.” He had a daughter with her, and, according to a recent article in the Spanish newspaper El Mundo, several more children with other partners.

After she found out that her husband was not a CIA agent but a child-molesting priest, Blanca Estela Lara did not come forth with the news that she was married to him. Perhaps she was terrified unawares of the man she believed “was her God,” as she would say a decade later. Perhaps she was simply ashamed. At any rate, she kept silent while some of Maciel’s victims and a few journalists—notably the late Gerald Renner and Jason Berry, now of the National Catholic Reporter—kept producing more evidence. And then, last March, two years after Maciel’s death, Lara appeared with her three sons on one of Mexico’s most well-regarded talk shows and listened quietly while her children testified that their biological father, Marcial Maciel, had made them masturbate him, and had first attempted to rape them, the older one said, when he was a boy seven years old. (This testimony has been tarnished somewhat by the revelation that the sons had earlier demanded millions of dollars from the Legionaries of Christ in exchange for their silence. The order has not attempted to deny the accusation, however.)

Advertisement

Quite apart from the damage to Maciel’s victims, there is the pressing question of why the Catholic Church, as an institution, did not condemn him when he was ordained as a priest, or when he founded the Legionaries, or when the story of his pederasty made the cover of magazines, or when enough evidence was found to conclude that Maciel should live out the rest of his life in seclusion, or even when the rumors grew strong enough to warrant a Vatican investigation of the order as a whole. The answer surprises no one: at a time in which churches are emptying, the Legionaries have been a rich source of conscripts, money and influence; in Mexico everyone from Carlos Slim to Marta Sahagún, the wife of former president Vicente Fox, gave money to or asked favors from Maciel.

It was not until last year that Karol Wojtyla’s successor, Pope Benedict XVI, at last authorized a visitation—churchspeak for investigation—of the entire order of the Legionaries of Christ. As usual, the press and some disaffected religious have been way ahead of the Vatican. Now we learn from the press that the order kept some 900 women under non-binding vows as consagradas, or quasi-nuns, in conditions of emotional privation and subjugation that violated even canonical law.

In the end, the scandal of Marcial Maciel, gruesome and ribald as it is, will turn out to be of much greater significance to the Catholic Church than the isolated terrors inflicted on their victims by one or another European or U.S. bishop or priest. There is the distressing question of the Church’s last Pope, the popular John Paul II, and his relations with the demonic priest. There is the not unimportant fact that the Legionaries—along with Benedict XVI and indeed John Paul—represent the most morally conservative part of the Church, and that they now appear enmeshed in the most squalid moral scandal it is possible to imagine. There is, above all, the fact that an entire, large, wealthy, international institution is now under suspicion (what did Maciel’s fellow Legionaries know, when did they know it, and who was complicit?) and that the greatest institution of all, the Roman Catholic Church, appears to have engaged in a cover-up for decades on its behalf. Catholics who always assumed that a priest and Bing Crosby were more or less identical will need some time to adjust to this knowledge.

But there is the also the question of the future of the Church and of its priests and nuns as sexual beings. It is not necessarily cheap psychology to speculate that extreme sexual repression of the sort imposed by the Church on its members leads to perversion, an issue that has surfaced importunately for the last millenium. Many religious, it would seem, opt to “obey” rules but not comply with them, as the Spanish formulation has it (“obedezco, pero no cumplo”). I offer this simply as anecdotal evidence, but in my casual, friendly, and often admiring acquaintance with members of the Catholic orders—all from the social activist branch of the church, for whatever it’s worth—a remarkable number have been involved in some sort of couple relationship.

I once attended a major church festivity in a small town at which several of the priests and nuns who arrived to concelebrate Mass were openly, and even defiantly, there with their partners, either homosexual or hetero. In 1979, at the time of John Paul’s first visit to Mexico, I had a conversation with a progressive Spanish priest who lived with his partner, a middle-aged woman, about the split life he lived. Why, I asked, didn’t he leave the Church if so many of its norms violated his own convictions and desire for honesty? I remember his saying, in effect, that the possibility of doing good within an institution as enormous and influential as the Church was greater that the chances for doing good outside of it. Perhaps that equation is changing.