This is the second of two excerpts from Metamaus, Art Spiegelman’s new book of conversations with Hillary Chute about the making of his Maus books. The first excerpt can be found here.

—The Editors

Hillary Chute: You mentioned your parents had some books about the war around the house when you were growing up. How did they inform your thinking?

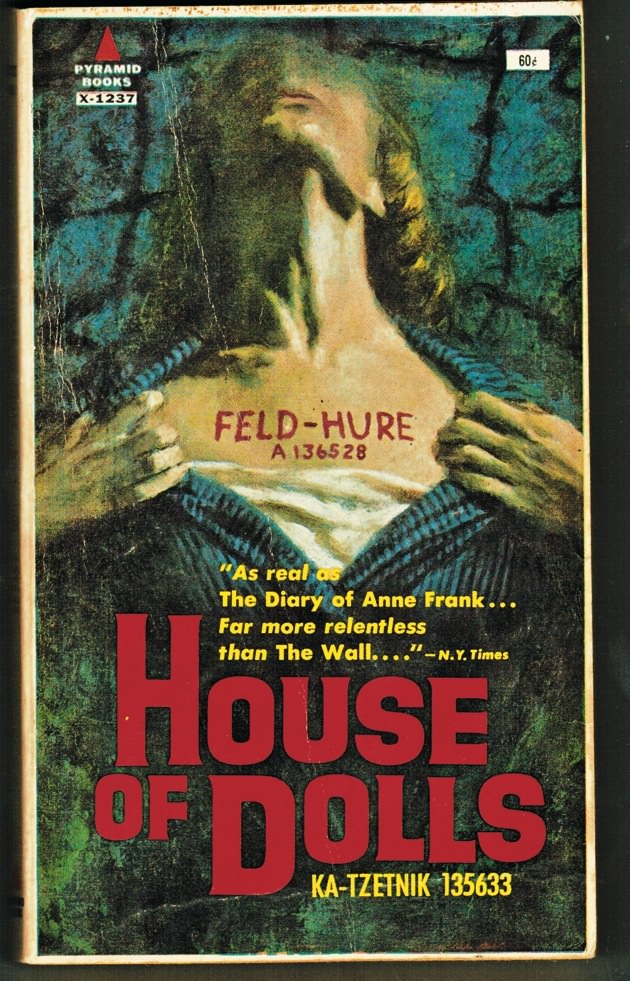

Art Spiegelman: Well, there were the small-press books I told you about, and one called The Black Book, a cataloguing of the atrocities- and one paperback on the same hidden shelf of forbidden knowledge that was about Aleister Crowley and Satanism called The Beast 666. Anyway all of it kind of sat together as a kind of semi-pornography for me. In fact, I think House of Dolls, a sleazily unhealthy fiction/memoir by a survivor that was a widely read paperback book in the fifties about the whorehouses of Auschwitz, might have been on that shelf too. Many years later I read Shivitti, a memoir by the House of Dolls author, Ka-Tzetnik, about his LSD therapy and revisiting Auschwitz on acid, and trying to come to terms with an incestuous relationship with his sister who died in the camps-what an astounding character! Anyway I read part of House of Dolls as pornography, which, I guess, is the way most people read it: as part of the whole leather-bondage sexy-Nazi pathology. As a kid, the connection between the pornographic aspect of the death camps—the forbidden, the dangerous and fraught—was all one big stew that I couldn’t separate out.

To say those books informed my thinking, or even to say I was thinking about this at all in my early teens, would give me too much credit. It was all just part of The Big Taboo. It occurs to me right now, though, that perhaps the whole taboo-smashing ethos of the underground comix scene did allow me to stir up the buried connections to the unspeakable that my mother’s secret bookshelf opened up.

When did you first come across drawings by survivors—or drawings by people who didn’t survive—and how did you find them?

Before embarking on Maus I consciously set about looking for material that could help me visualize what I needed to draw. The few collections of survivors’ drawings and reproductions of surviving art that I could get my hands on were essential for me. Those drawings were a return to drawing not for its possibilities of imposing the self, of finding a new role for art and drawing after the invention of the camera, but rather a return to the earlier function that drawing served before the camera—a kind of commemorating, witnessing, and recording of information-what Goya referred to when he says, “This I saw.” The artists, like the memoirists and diarists of the time, are giving urgent information in the pictures, information that could be transmitted no other way, and often at great risk to their lives.

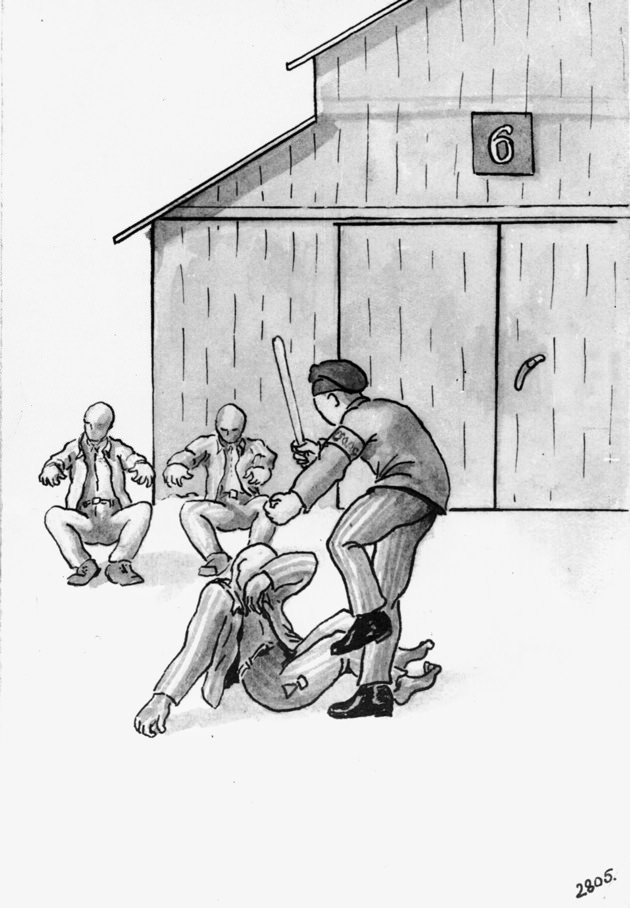

At one point in the book [my father] says they didn’t have watches at Auschwitz. They didn’t have cameras either, for the most part, in Auschwitz. There were some contemporary photographs to look at, but most of what happened was not photographed. There aren’t really a lot of photographs of inmates in Auschwitz being beaten. But there are drawings by people who were beaten of what was happening to them. And those drawings range in levels of craft and skill from rather primitive—people who had virtually no graphic art training—to people who were incredibly skilled artists who even had access to art supplies in Auschwitz.

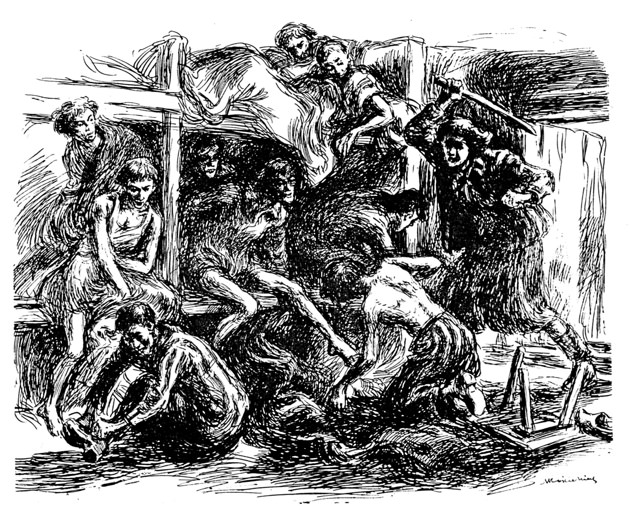

Some of the often anonymous art I found could simply help me understand what, say, a barrack looked like. One drawing, for instance, shows a kapo beating up a prisoner. One gets to see that the beating is being done with a stick, while in the background there are prisoners who are made to squat and watch and just keep their hands raised to the point of exhaustion, and it’s all taking place in front of one of these Birkenau-style barracks. There’s just enough information for you to see wooden shoe versus leather shoe, what kind of patches were put on the uniform. It’s very convincing as a drawing, and it’s very touching as a drawing because it’s not drawn well. And one can only imagine what lengths the artist had to go to bury that drawing somewhere and not be caught with what would have been a death sentence.

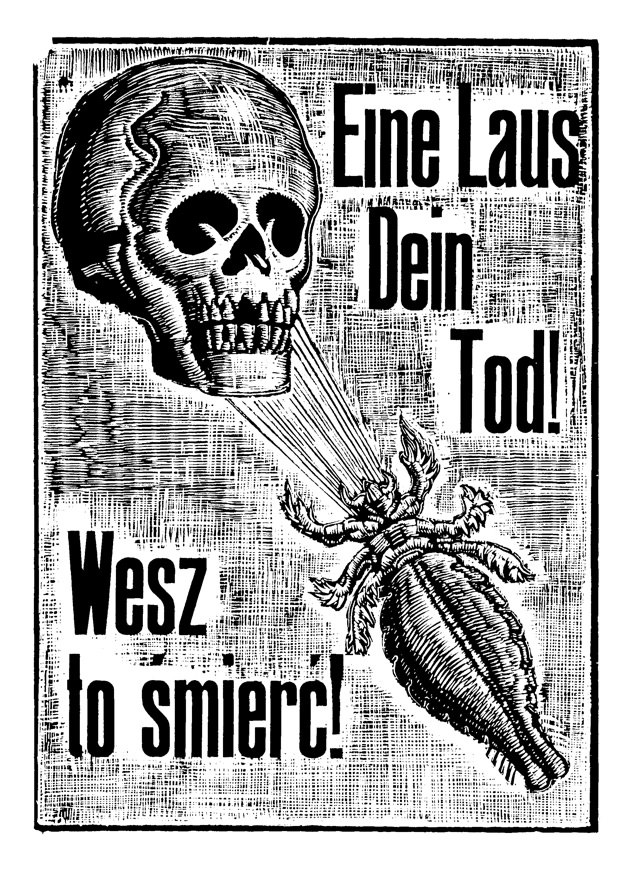

Some of the drawings that were among the most important to me were by an artist named Mieczysław Kościelniak. He was a very skilled, academically trained Pole, not Jewish, and therefore was able to get a job in the art barrack, basically, doing genealogies, signage, portraits of SS men in Auschwitz. There was a poster in Auschwitz that I’ve often seen reproduced, that says, “One Louse Means Death.” That was his day job. But then secretly he went back into that studio and did several suites of drawings, one called “The Prisoner’s Day, Auschwitz,” another one called “The Prisoner’s Day, Birkenau.” And there aren’t that many images, maybe twenty pictures in each suite of drawings—rather detailed, really well represented drawings of the roll call, hauling the cans of soup, the quotidian moments of life in the camp presented very convincingly, and with a clarity beyond most photography. They were as close as one could get to seeing it directly. So, inevitably, I pored over those things and whatever photos I could dig up, Kościelniak’s drawings had the detailed content I needed to re-abstract back toward my simple comics panels.

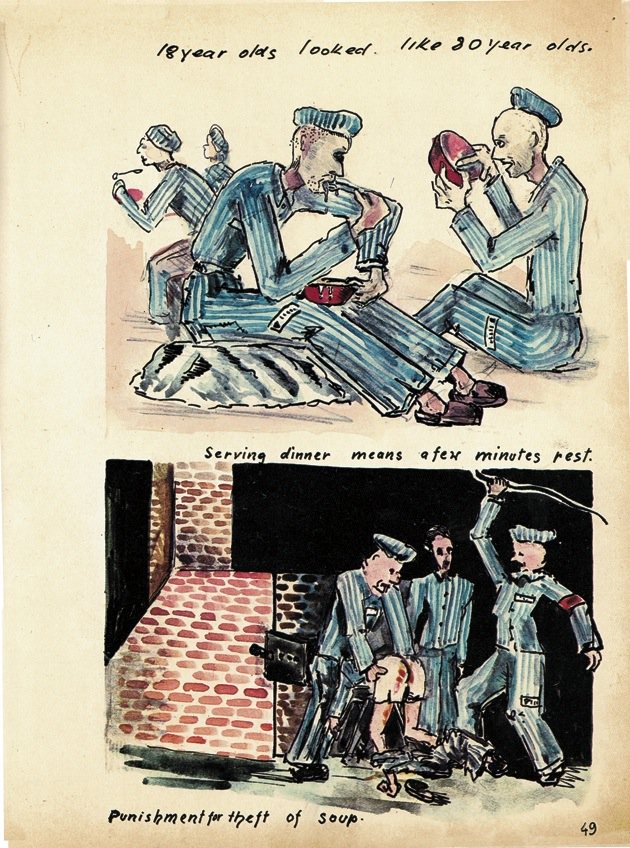

Alfred Kantor was also an amazing resource. Kantor was a teenager in Terezin and Auschwitz, evidently drawing to keep himself sane, drawing what was around him. He destroyed most of the drawings he made while in Auschwitz, but reconstructed them while he was in a DP camp right after the war. At that point, now that the drawings would no longer cost his life, he redrew a visual diary of what he’d just gone through, He went on to a successful career in advertising.

Late in his life a friend saw it and encouraged him to publish The Book of Alfred Kantor, which—for somebody with my doubletrack disposition toward reading and looking—was an important clue to the moment-to-moment texture of life in a death camp. Kantor was drawing many of the same places and situations my parents were in, so his book became indispensable.

MetaMaus, by Art Spiegelman, has just been published.