I have no idea what Clint Eastwood had in mind when he dragged an empty chair up to the stage at the Republican Convention in Tampa last August. Maybe he was thinking, as some have suggested, of some bygone exercise in a Lee Strasberg acting class. “Please, Clint. Talk to the chair. You are Hamlet and the chair is Ophelia. Please. Just talk to her.” Or maybe a marriage counselor had used an empty chair to teach the tight-lipped gunslinger from Carmel how to empathize with his wife. “Go ahead, Clint, make her day. Tell her what you’re feeling.”

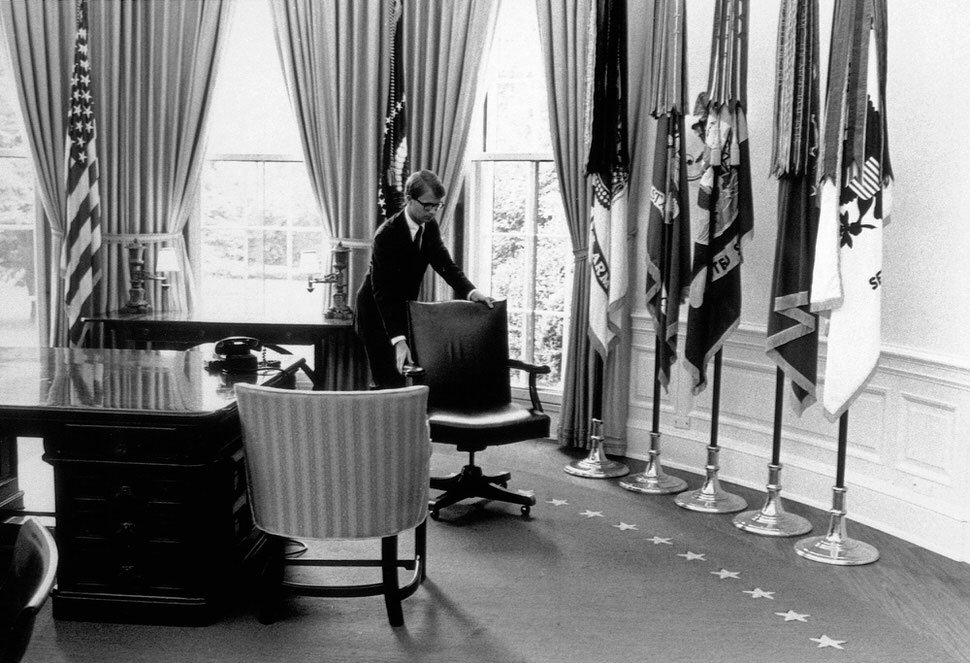

I was thinking of that empty chair in Tampa as I watched Tuesday’s presidential debate at Hofstra University. I was thinking what our country would be like, what the world would be like, without Barack Obama seated in the Oval Office. That’s the empty chair that keeps me awake at night.

Where have we seen empty chairs before? We’ve seen them in the memorial to the victims of the Oklahoma City bombing, a field of 168 empty chairs on the footprint of the Murrah Building. We’ve seen empty benches placed outside the Pentagon to commemorate the victims of 9/11. Empty chairs in Buddhist, Roman, and Christian art are symbols of mourning, of loss, of lament. Remember Van Gogh’s great painting of Gauguin’s empty armchair in his bedroom in Arles, in memory of his departed friend? Or the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to the imprisoned dissident Chinese writer Liu Xiaobo two years ago, when the diploma and medal were placed on the empty chair reserved for Liu?

Who do we want in the president’s chair, making decisions when the next crisis—and we know there will be a next crisis, and a next—erupts? An Oval Office occupied by Romney would suffer from a different kind of vacancy, a void of ideas or convictions, a sketchy foreign policy based on China-bashing and pandering to his old pal Bibi. During Tuesday’s debate, Romney, flashing his fatuous neon smile, must have begun twenty sentences with a variant of the phrase “I know what it takes”—a phrase that conveniently obfuscates precisely which tax loopholes he would close, how he’d bring peace to the Middle East, or how in the world his magical math might “add up.”

What might it take, a young woman in the audience asked, to achieve equality in the workplace for women? Romney’s answer, to this and many other questions, was more jobs, 12 million of which he will create in four years, because he “knows” what it takes to get this economy growing. And if women are excluded from the best jobs? Well, he’ll do what he did as Governor of Massachusetts—that land of bipartisanship, balanced budgets, and opportunity for all that he has suddenly rediscovered, after barely mentioning it in the Republican debates—when he called for a “binder full of women” to staff his cabinet.

I remember my first presidential campaign. I was six years old. John F. Kennedy came to our little backwater in Indiana to speak at the local college. I sat in a folding chair in the audience, feeling important, feeling that I was watching and hearing something important. Three years later, oblivious that the world had changed, I walked home from school to find my mother, who had just heard the awful news from Dallas, sobbing uncontrollably in the kitchen. The empty chair.

Five years later, another election year. I had been playing quartets downtown in our sleepy Indiana town under the watchful eye and ear of an exacting German named Koerner. I was heading home, carrying my black viola case across the G Street Bridge, when there was a huge explosion. Six blocks of our downtown went up in smoke, and a giant mushroom cloud hovered in the sky, like a nightmare version of the nuclear war we all trained for at school, huddled under our desks during the civil defense drills. It turned out that a local sporting-goods store had been stockpiling ammunition in case our black neighborhoods erupted after the murder of Martin Luther King. Our downtown did erupt, but it had nothing to do with riots.

The date was April 6, 1968. Forty-one people died in an instant, for nothing, because of their neighbors’ irrational fears. More empty chairs.

These days—can’t we all see it and feel it?—there’s a tragic dimension to the Obama presidency, and not just because so many people in this country and abroad want him dead. Republicans in Congress have blithely stonewalled everything a president is elected to do; our federal courts are full of vacant seats, while key administrative positions, such as the head of the new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, have been held hostage to the deliberate Republican strategy of humiliating the president.

Advertisement

Meanwhile, empty chairs hanging from trees have appeared in Virginia and Texas, eerie reminders of lynchings, and of the depth of hatred this man inspires. To demonstrate solidarity with Clint Eastwood’s shabby performance in Tampa, movement conservatives like Michelle Malkin called for a “National Empty Chair Day”—on Labor Day, no less. She added, “It’s fun. It’s funny.”

Romney seemed to think it was funny, at Hofstra, to suggest that Obama, campaigning in Las Vegas, had ignored the deaths at Benghazi, or, worse, had been “misleading” the American people about what happened there. Obama was firm in his have-you-no-shame response, taking responsibility (despite Hillary Clinton’s claim earlier in the day that she was in charge) for security and reminding voters that he is a wartime president, with all that that entails.

The tragic dimension is there in the President’s face and in his shoulders. It was there, visibly there, in his performance in the first debate—not “lackluster,” as it was widely described, but burdened, bedeviled, fraught. Not for nothing did he invoke, and quite rightly, Abraham Lincoln. During the second debate, he was more combative, confrontational, locked in. But what came through most strongly was the contrast between Romney’s vacuous claim to care for 100 percent of all Americans (since we’re all “children of the same God,” he can apparently include even the 47 percent who are moochers), and the detailed ways, the detailed policies, in which Obama has actually shown that he cares for all of us.

The tragic dimension of the Obama presidency is there in his willingness to take on the fate of the world, our fate. It’s there in his willingness to stand up for both black and white Americans, for both poor and prosperous Americans, for Libya and Egypt and Yemen as well as for Israel and a partially united Europe.

The empty chair. The empty suit. The empty-headed gunslinger from Belmont, armed with his magic wand and his Etch A Sketch. The empty Mitt.

Clint, ole boy, we can’t afford it, not for a fistful of dollars.