Spring Breakers, the new film by Harmony Korine, opens with an impressively staged shot of pure pulchritude—a mass of golden bodies gyrating on a Florida beach—rendered somewhat absurd by the cartoonish sounds of Skrillex’s wacky techno distortions. The luridly saturated colors are pure Pop Art. The casting is conceptual. Korine employs a pair of Disney teen princesses—Selena Gomez and Vanessa Hudgens—along with TV soubrette Ashley Benson and his wife, Rachel Korine, to play a quartet of co-eds who escape from their emphatically non-Ivy League college to join in the spring break frenzy. That these students are too busy establishing their sexual bravado to heed their professor’s droning lecture on the civil rights movement, however, signals that Spring Breakers has more on its mind than youth’s inalienable right to party.

Spring Breakers is a crowd-pleaser, although given its confounding creepiness, the crowd it pleases most is surely the forty-year-old filmmaker’s intellectual fan base. Korine’s college girl protagonists finance their trip by stealing a car and robbing the local Chicken Shack, using toy guns and moves swiped from Quentin Tarantino movies. (“Just pretend it’s a fucking video game,” the leader advises her cohort.) The robbery is filmed as Brian De Palma might, in a continuous take as watched outside from the revved-up getaway car. Down in Florida, all four join the bacchanal, get busted—for reasons never made clear—and, in the movie’s most lubricious stunt, are locked up, still in their bikinis. They never seem more vulnerable or freer.

Then the movie turns. A knavish knight errant arrives in the form of an impossibly skeevy rap-artist-cum-dope-pushing-gun-dealer called Alien (played by James Franco, with corn-rows and a set of gleaming grillz). He bails them out and takes them under his wing, leaving the audience to wait for the worst or imagine it. Alien’s home is a literal trophy house, a palace consecrated to consumable iniquity, overstocked with weapons and drugs. Bouncing on the trampoline-sized bed, the girls, who have been reduced in number to three (Selena Gomez’s character, a young Christian named Faith, has gone back to campus), turn his guns on him and make him fellate the barrels. Unabashed, the now feminized Alien leads the trio in singing the wistful ballad “Everytime,” a song written by the best-known of fallen mouseketeers, Britney Spears. Then, together they go on to terrorize a few hapless male spring breakers, who have been amusing themselves drenching their comatose female counterparts with an ocean of beer, and participate in Alien’s comparably ineffectual vendetta against his African-American rival (rapper Gucci Mane). Alien goes down but the surviving girls are like Valkyries who whisk themselves up to Valhalla, chanting the movie’s inane mantra: “Spring break for-evah!”

Korine has enjoyed a healthy career as a provocateur and Spring Breakers, however extravagantly prurient, marks his entry into middle-age; it feels mature. Korine hasn’t exactly aged out of nihilism but the movie’s production values do suggest the work of a man with a career to maintain and a producer’s investment to protect. It’s been eighteen years since Korine wrote his first screenplay, Kids (1995), the avid exposé of unprotected, young teen sex in New York City during the AIDS crisis directed by photographer Larry Clark. Korine’s subsequent movies Gummo (1997) and julien donkey-boy (1999), both made before he turned twenty-six, were more deliberately off-putting, candy-colored freak shows alternately disgusting or stupefying.

After furnishing Clark with another script, Ken Park (2002), that revisited the world of addled teens, this time in suburban California, the enfant terrible laid low before showing his sensitive side with Mr. Lonely (2007), a tepid, French production in which a Michael Jackson impersonator has a fleeting romance with an ersatz Marilyn Monroe. This was followed by the movie I regard as his best, the daringly low-tech Trash Humpers (2009), purportedly a deteriorated VHS tape of inane acting-out in a derelict landscape, in which a cadre of supposedly geriatric punks, often in wheelchairs, stage a sort of desecratory anti-social guerrilla theater. Slick and stylish, Spring Breakers would appear to be Trash Humpers’s polar opposite but it too flirts with the déclassé; in essence the movie puts a Duchampian frame around the Girls Gone Wild genre of documentary soft-core porn, if not its hard-core online analogues.

It’s unlikely that, outside the world of international film festivals, Korine was ever saddled with the burden of being a generational spokesperson but, in any case, that position is now occupied by Lena Dunham, who at twenty-six is scarcely older than Korine was during his initial successes of the 1990s. With Girls, her ubiquitous HBO series in which a quartet of relatively privileged young women, recently graduated from college, try without much success to navigate a world of dead-end jobs and deadbeat boyfriends, Dunham has tapped into a vein of tragicomic sexual naturalism in which, as in the novels of Czech writers Milan Kundera and Ivan Klima, social constraint (here economic) makes sex, however messy, the lone arena of freedom.

Advertisement

The pseudo “money shot” in the penultimate episode of this past season’s Girls in which, having sexually humiliated his annoying new girlfriend, the protagonist’s ex climaxes on her chest is at once more diffident and more shocking, not to mention more authentically Girls Gone Wild, than anything in Spring Breakers. I’m not alone in sensing a kinship between Korine and Dunham—or Spring Breakers and Girls. The Hollywood Reporter produced a mash-up in which Dunham’s character Hannah Horvath engages in split-screen dialogue with Alien, allowing the viewer to compare their various raps and tattoos—while imagining Hannah’s experience of Easter in Florida. The real connection lies in their programmatic use of the nubile body. The female form is their canvas.

Two prodigies, Korine and Dunham both grew up in bohemian milieus, the children of artists. That Korine’s father Sol was a PBS documentarian specializing in Southern subcultures offers a particular path into his son’s work, feasting as it does on fancifully lumpen redneck antics in films like Gummo or Trash Humpers. Dunham actually cast her real mother, photography-artist Laurie Simmons, as her on-screen mother in her quasi-autobiographical first feature Tiny Furniture (2010), which also served to satirize Simmon’s art, involving dolls and miniatures. Lena’s father, Carroll Dunham, is a successful painter and, although he declined to appear in his daughter’s movie, it’s hard to miss, if not necessarily explain, the affinities between her work—which so often involves placing her ample, unclothed self in awkward situations—and his cartoonish paintings of rotund young women, seen from the rear and sometimes bending over as they bathe in a wildly phallic landscape.

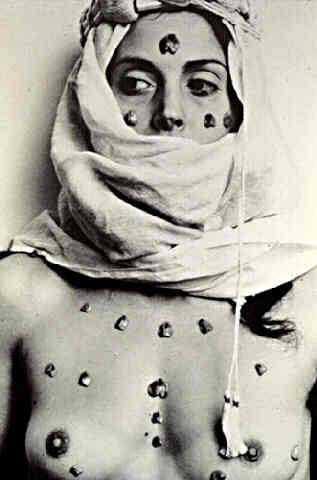

Dunham is a burgeoning New Yorker humorist in the tradition of Woody Allen, and a post-Roseanne, post-Seinfeld self-dramatist who simultaneously creates and comments on a fictional world revolving around an exaggerated alter-ego. When I watch Girls, however, I see her less as an exponent of sitcom psychodrama than as someone who has given a narrative dimension to those activities classified in the early 1970s as Body Art. Dunham’s method of self-portraiture recalls the late performance artist Hannah Wilke (née Arlene Hannah Butter), who frequently put her own naked body on display (and as a somewhat older and wilder contemporary from a similar suburban background, surely must have played some part in the aesthetic formation of Dunham’s mother). Dunham’s exhibitionism, already evident in the videos that she made while an undergraduate at Oberlin, has been well-noted in the commentary on Girls as the show’s trademark—along with her character’s astonishing and less-than-likeable self-absorption.

Hannah Wilke satirized art-world sexism by presenting herself as a pin-up, sometimes adorned with vaginally-shaped pieces of chewing gum. Dunham’s character in Girls, Hannah Horvath, dresses badly and undresses frequently; self-abnegating and ungainly, she regularly challenges social attitudes that are even more ingrained. Indeed, as the second season came to an end, Dunham grew all the more assertive in establishing Hannah’s physicality—developing a tic, twitches, and a boil on her buttocks, injuring herself by jamming a Q-Tip in her ear. Her show is a hall of mirrors in which Girl Power and female powerlessness are endlessly reflected.

With its hot-bod young delinquents, Spring Breakers is hardly a critique of gender stereotypes, no matter how much its co-eds humiliate the seemingly dangerous Alien or claim ownership of the term “bitch.” Where the actresses in Spring Breakers collude in their own abasement, Dunham uses hers as a weapon. Scarcely less debauched than Spring Breakers and equally an expression of directorial will, Girls is a far more complicated and troubling creation. The spectacle that Dunham makes of herself does not offer the illusion of liberation, except that, in fact, that’s exactly what it is.