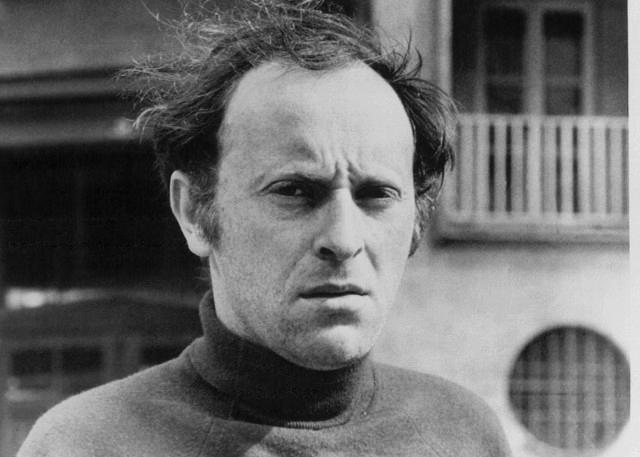

To celebrate National Poetry Month, The New York Review is posting poems and articles by poets and critics whose work in the magazine has spanned a period of years or decades. For this second week of April, we will be focused on the writing of Joseph Brodsky (1940–1996).

Brodsky was a Russian poet and essayist. Born in Leningrad, he moved to the United States in 1972 following his expulsion from the Soviet Union. His poetry collections include A Part of Speech (1980) and To Urania (1988); his essay collections include Less Than One (1986) and Watermark (1992). He was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1987 and served as US Poet Laureate in 1991–1992.

April 14

Some five years after arriving in the United States, Brodsky wrote this wide-ranging review of a study of Constantine Cavafy’s poetry, touching on his relationship to Greek and Roman history, his sexuality, and the limitations of his own biography (having never left his provincial Alexandria). “By the turn of the century,” Brodsky writes, “Cavafy had acquired that objective, although properly ambiguous, dispassionate tone that he was to employ for the next thirty years. His sense of history took hold of him, but first of all, stylistically: it gave him a mask.”

On Cavafy’s Side

February 17, 1977

On Cavafy’s Alexandria: Study of a Myth in Progress by Edmund Keeley

More »

April 13

Two Poems

February 18, 1988

North Baltic

When a blizzard powders the harbor, when the creaking pine

leaves in the air an imprint deeper than a sled’s steel runner,

what degree of blueness can be gained by an eye? What sign

language can sprout from a chary manner?

Falling out of sight, the outside world

makes a face its hostage: pale, plain, snowbound.

Allenby Road

At sunset, when the paralyzed street gives up

hope of hearing an ambulance, finally settling for

strolling Chinamen, while the elms imitate a map

of a khaki-clad country that lulls its foe,

life is gradually getting myopic, spliced,

aquiline, geometrical, free of gloss

or detail—be it cornices, doorknobs, Christ—

stressing silhouettes: chimneys, rooftops, a cross.

April 12

Via Funari

February 1, 1996

Ugly gargoyles peek out of your well-lit window,

the Gaetani palace exhales turpentine and varnish,

and Gino’s where the coffee was good and I used to pick up the keys,

has vanished. In Gino’s stead

came a boutique; it sells socks and neckties,

more indispensable than either him or us

—from any standpoint, actually.

April 11: Anna Akhmatova

This 1973 review of Stanley Kunitz’s translations of Anna Akhmatova was Joseph Brodsky’s first article for the Review. Brodsky had been close to Akhmatova from their first meeting in the early 1960s; as Isaiah Berlin remarked after Brodsky’s death, Berlin wished he’d known Brodsky “then, in the Akhmatova years, because everything was sown and came to fruition at that time, and the emigration years were merely the reaping of the harvest.”

Translating Akhmatova

August 9, 1973

Russian poetry has not been lucky with its translations into English. It has been so unlucky that it may seem that the problem is in the Russian language itself—a synthetic, too flexible language which cannot be reproduced adequately in analytic English with its “iron word-order.” Successful translations are rare.

You can hear Brodsky talking about Akhmatova in this radio program for RTÉ by Mary Russell, “The Stars of Death Stood Over Us.”

April 10

From “A Part of Speech”

December 20, 1979

I was born and grew up in the Baltic marshland

by zinc-gray breakers that always marched on

in twos. Hence all rhymes, hence that wan flat voice

that ripples between them like hair still moist,

if it ripples at all. Propped on a pallid elbow,

the helix picks out of them no sea rumble

but a clap of canvas, of shutters, of hands, a kettle

on the burner, boiling—lastly, the seagull’s metal

cry. What keeps hearts from falseness in this flat region

is that there is nowhere to hide and plenty of room for vision.

Only sound needs echo and dreads its lack.

A glance is accustomed to no glance back.

April 9: How “language can triumph when empire fails”

Brodsky’s book of essays Less Than One was published in 1986, the year before he received the Nobel Prize for Literature. John Bayley reviewed it, situating Brodsky in a “vanished world of civilization and humor.”

Mastering Speech

John Bayley

June 12, 1986

Brodsky’s title piece, “Less Than One,” takes us back to his St. Petersburg childhood, and “A Guide to a Renamed City” is a wonderful evocation of the former capital, a city in which a man “spends as much time on foot as any good Bedouin.” Although Less Than One is vitriolic on the subject of Russian politics, the general effect of these essays is of an intelligence as lyrical and benign as Auden’s own.

April 8: An elegy for a friend

Brodsky discovered W.H. Auden’s work while in internal exile in the Arkhangelsk region of the Soviet Union. It struck an immediate chord with him and it was subsequently arranged, through intermediaries, for Auden to write an introduction to Brodsky’s first book in English, launching his career in the English language. Serendipitously Brodsky’s eventual exile took him to Austria in 1972, where he found Auden and they forged a friendship that lasted until Auden’s death in September 1973. This poem, written by Brodsky in English, appeared in the Review the following year.

Advertisement

Elegy to W.H. Auden

December 12, 1974

The tree is dark, the tree is tall,

to gaze at it isn’t fun.

Among the fruits of this fall

your death is the most grievous one.

The land is bare. Firm for steps,

it yields to a shovel’s clink.

Among next April’s stems

your cross will be the unshaken thing.