Our retrospective image of 1930s America derives in large part from Norman Bel Geddes (1893–1958), the self-taught polymath who virtually invented the profession of industrial design. Thanks to Geddes and his pioneering New York firm, these were the years of Streamline Moderne, a particularly American variant of Modernism—smoother, softer, and more accessible than the stringent machine aesthetic of Le Corbusier or the late-phase Bauhaus.

Yet Geddes never quite found a place in the pantheon of American high style designers, and the fascinating survey that the curator Donald Albrecht has put on at the Museum of the City of New York therefore comes as something of a rediscovery. Handsomely installed by architect Wendy Evans Joseph, “Norman Bel Geddes: I Have Seen the Future” stresses Geddes’s ability to convince people that even his most pie-in-the-sky proposals (including a vast flying hotel, like some airborne cruise ship) were just as attainable as his workaday home appliances.

Geddes was a quintessentially American success story, having risen from a straitened Midwestern boyhood to become the toast of Manhattan by patterning himself in equal parts on the Arts and Crafts popularizer Elbert Hubbard and the huckster impresario P.T. Barnum. That high/low melding made him rich, but prevented him from being taken seriously by the architectural establishment. That many of his concoctions were impossible never fazed Geddes, who was raised a Christian Scientist and internalized Mary Baker Eddy’s positivist credo of “mind over matter.”

Geddes’s early success as an innovative theatrical designer—his dramatically lit, minimalist sets were part of the New Stagecraft movement—reinforced his belief in the power of illusion and ability to undertake increasingly grandiose projects. However, without formal architectural education, he termed himself an “architecturalist” and needed accredited collaborators to certify his building plans.

A primary source for Streamline design was the German architect Erich Mendelsohn, whom Geddes met in 1924. Mendelsohn’s dynamic, crowd-pleasing commercial buildings featured curved corners, wrap-around horizontal bands, and elongated proportions—motifs that the Geddes firm adapted for everything from practical household objects like refrigerators, lamps, and vacuum cleaners, to hypothetical plans for mechanized theaters, amphibious cars, and floating airports.

On the one hand, Geddes wanted streamlining to seem like scientific inevitability. As he asserted in Horizons (1932), “It is a well known fact that a drop of water falling in still air assumes an almost perfect streamline form.” On the other hand, he was a shameless self-promoter who, in an ad for the 1934 Chrysler Airflow, which he helped to style, praised it as “the first sincere and authentic streamlined car…the first real motor car.”

The common thread uniting Geddes’s built designs and futurist visions was his celebration of planned obsolescence (annual introductions of new models were supposed to make older ones seem passé and undesirable, even if they still worked well). He believed that a constant stream of irresistibly novel products would reinvigorate manufacturing and the economy at large, through an endless cycle of increased consumer spending.

Idealistic European advocates, however, posited modern design as just one component of a thoroughgoing program that would reform all aspects of society. The great divide between the utopian and the mercantile was enforced in America by the moralizing founding director of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, Alfred H. Barr, Jr., who deemed Streamline Moderne too crassly commercial for his high-minded institution.

When Geddes, in a 1934 Atlantic Monthly article, “Streamlining,” outlined the principles of aerodynamics undergirding his design concepts, Barr responded with prissy hauteur. “It seems to me that streamlining has been an absurdity in much contemporary design,” he wrote to the author. “This blind concern with fashion is one of the things that makes it difficult to take the ordinary industrial designers seriously.”

Barr considered such aerodynamic styling permissible only as an aid to function in moving vehicles—trains, airplanes, boats, and automobiles—or in the torpedo he famously used to diagram his theory of modern art advancing into the future. To this day, Geddes is not represented in MoMA’s collection, while the more inclusive Metropolitan Museum of Art owns sixteen of his objects, ranging from a chrome-plated cocktail shaker to his plastic Emerson Patriot radio.

In 1944, a year after Barr was ousted as its director, MoMA exhibited Geddes’s war maneuver models, realistic miniature recreations of decisive Pacific naval battles commissioned by Life magazine to give its readers an accurate impression of the far-off theater of war. Geddes had a genius for using relatively low-tech means to achieve highly convincing effects, and his vivid photographic evocations enthralled anxious observers on the home front before the advent of instantaneous press coverage. (His fondness for military models and interest in the technology of armaments extended to the “war games” he staged at his Manhattan apartment, an odd enthusiasm in a time of notably escapist entertainments.)

Advertisement

With consumer goods manufacturing suspended during the war, tensions grew within the Geddes office over the direction the firm should take, and several of his most talented assistants (including Henry Dreyfuss, Russel Wright, and Eliot Noyes) left to set up rival agencies. When peace came, Geddes, plagued by ill health, never returned to his prewar prominence. He tried to adjust to a changing society by designing Copa City (1948), a hybrid broadcasting studio, theater, and department store in Miami, and a scheme, never executed, for the first sports stadium with a retractable roof.

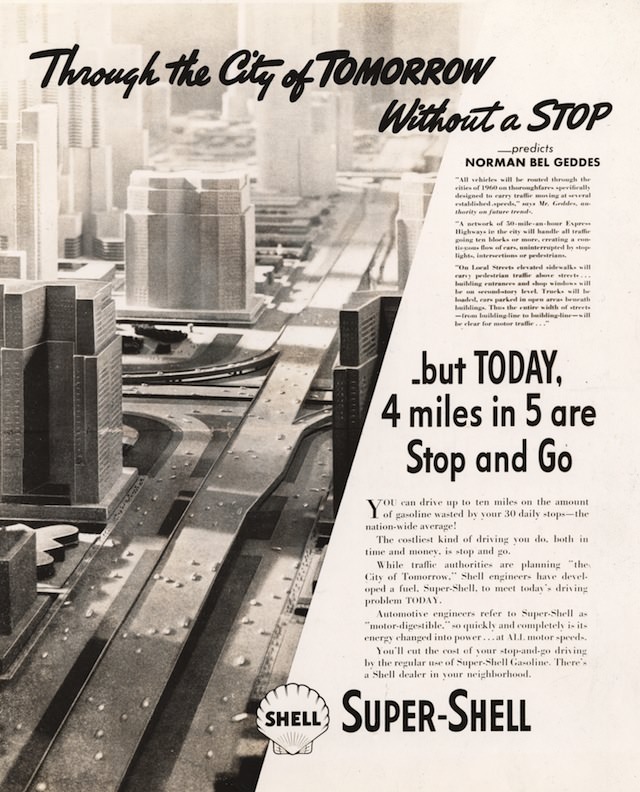

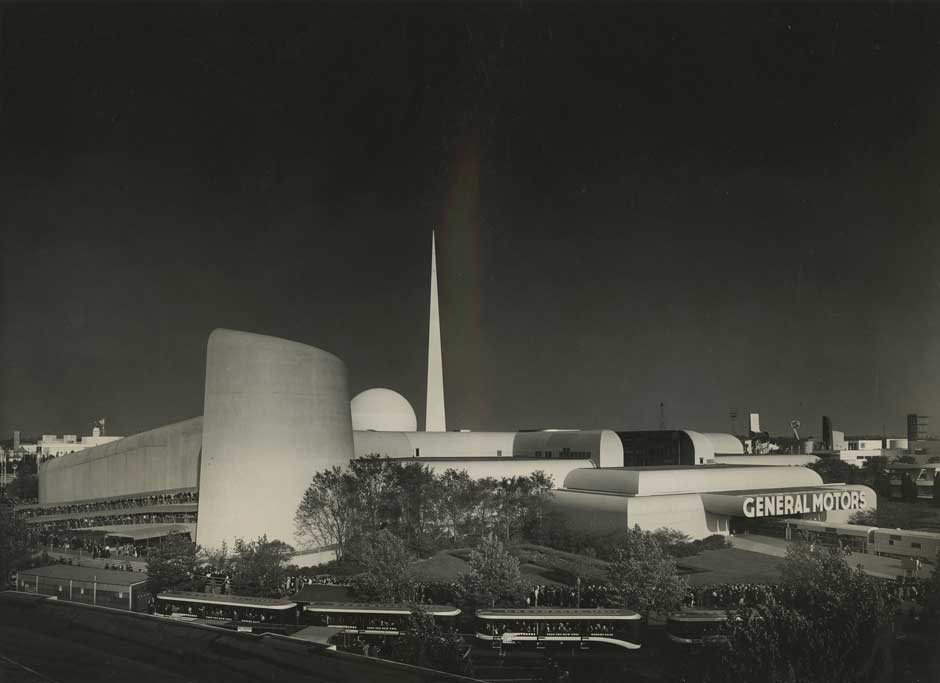

Geddes’s masterpiece was the General Motors Pavilion at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, an ingeniously planned experience titled “Highways and Horizons,” popularly known by its catchier moniker, Futurama. Among the designers of this sinuous structure was the young Eero Saarinen, architect of later biomorphic landmarks in the same mode. It enveloped a dazzling multimedia spectacle that anticipated by several decades the imaginative theme park attractions of the Disney Company as well as the immersive information presentations of Charles and Ray Eames.

Visitors lined up for hours along undulating ramps that dramatized Geddes’s cherished curves and streamlines. Indoors, they took their place in a continuous row of enclosed seats that ran sideways along a track like an amusement park ride; as they moved, they looked down on a series of intricately detailed small-scale models that purported to show aerial vistas of the United States in 1960.

Yet this wonderland of widely spaced skyscrapers interspersed with broad highways and speeding cars was directly inspired by Le Corbusier’s Plan Voisin of 1925, the fortunately unexecuted scheme that called for wholesale destruction of huge swaths of Paris’s historic Right Bank.

As wide-eyed fairgoers glided along, loudspeakers built into each seating unit played an uplifting recorded narrative that described the idyllic tableaux below. Given the pavilion’s corporate sponsorship, the exhibition did not voice the slightest reservation about the possible drawbacks of such an automobile dominated society. But neither would there be there much resistance in postwar America to the further ascendance of our oil-dependent car culture, with all the geopolitical and environmental catastrophe it was destined to bring by the end of the millennium.

Even Lewis Mumford, who would become the harshest postwar critic of America’s automobile fixation, was charmed. In his 1939 New Yorker review of the fair, Mumford wrote that

…Mr. Geddes’s landscape is marvelously good….I am not sure how [he] would get rid of the snow if a blizzard struck one of these highways or how he could keep the lighting system from being paralyzed then, but he has done a lot of research on the problem, according to report, so probably he knows.

In fact, those were precisely the kinds of things Geddes did not bother to think about. Mumford, the great exponent of regional planning, was beguiled by the panoptic scope of Futurama’s vision and as taken in by it as the least informed layman.

At the conclusion of this all-too-prophetic trip to tomorrow, visitors exited the internal portion of the adventure and stepped into the open-air heart of the freeform complex: a full-scale outdoor mockup of a streamlined traffic intersection, where brand new G.M. vehicles stood as if stopped at a perpetual red light. When guests left the astounding showplace, they were given a lapel button that proclaimed, “I Have Seen the Future,” though in hindsight the slogan’s real portent was not quite what the relentlessly upbeat Norman Bel Geddes had in mind.

“Norman Bel Geddes: I Have Seen the Future” is on view at the City Museum of New York through February 10, 2014. An accompanying catalog, Norman Bel Geddes Designs America, is available from Abrams.