As Senator Mitch McConnell, an outspoken opponent of regulating campaign spending, has conceded, trying to put limits on political donations is not easy. In McConnell’s words, it’s “like putting a rock on Jell-O. It oozes out some other place.” But if it was difficult before the Supreme Court’s decision this week in McCutcheon v. FEC, it is likely to be impossible now.

It was precisely to address the possibility that wealthy people might try to circumvent restrictions on political contributions that Congress not only limited how much money individuals can directly give to political candidates, but also capped the total amount they can donate to all candidates in any election cycle. The Court’s most recent decision, by invalidating all aggregate limits on donations, has vastly increased the amount of Jell-O that campaign finance laws now must contend with. And still more disturbingly, the decision’s rationale invites further challenges to Congressional limits on campaign spending. When this Court gets through, there may be no rock left at all—only Jell-O.

For the vast majority of Americans, the rules were hardly onerous before: it must be nice to have so much money that you find it constraining to be told you can only donate $123,200—or more than twice the annual income of a median US household—per election cycle to your preferred candidates. But for those who do bridle at such constraints, the Court has now recognized a constitutional right to spend much more, so that you are in fact free to donate millions of dollars to candidates, party committees, and PAC’s each election. (And that’s on top of a right to spend unlimited amounts on uncoordinated, independent support for your favorite candidates). Shaun McCutcheon, the man who challenged the $123,200 restriction and prevailed in the Supreme Court, must be laughing all the way to the halls of Congress.

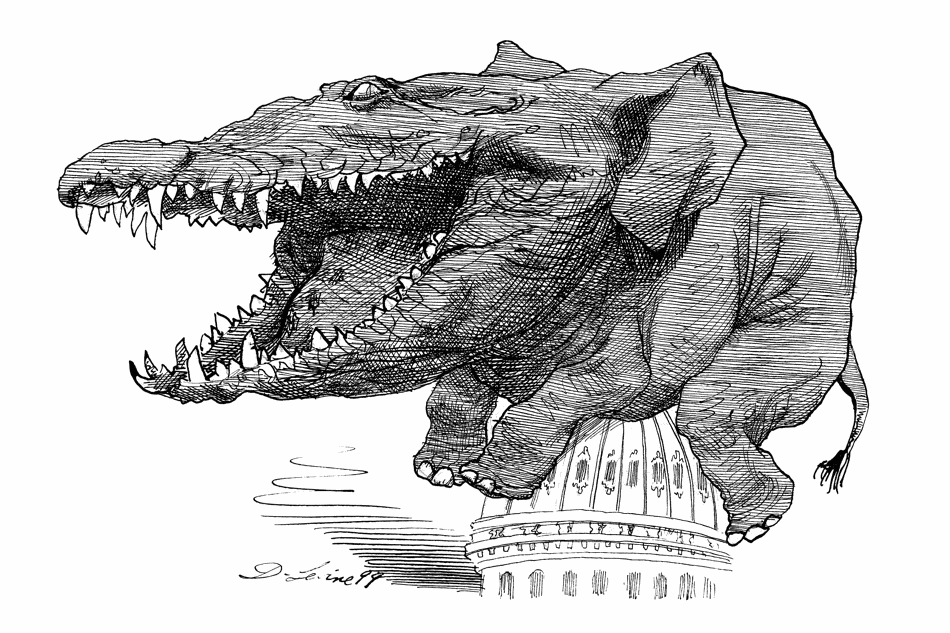

In McCutcheon v. FEC, the Court’s conservative majority once again vindicated the rights of the rich and mighty to spend as much as they want on political campaigns, overturning Congress’s efforts to limit the distorting influence of money. The Court did so by the same 5-4 vote by which it has decided every campaign finance case since the appointments of Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Samuel Alito. Through these decisions, those with inordinate wealth, like the Koch brothers and Sheldon Adelson, have been freed to spend their money to get the candidates who best represent their interests elected, while the rest of us are relegated to the sidelines. American democracy may be predicated, as a formal matter, on a guarantee of one person, one vote. But these days, the American system seems to be closer to one dollar, one vote.

Court followers have seen this coming since the Court’s infamous 2010 decision in Citizens United v. FEC, which held that corporations could not be restricted in political expenditures. At the time, many commentators focused their criticism on the fact that the Court equated corporations and human beings when it comes to First Amendment rights of free speech. But McCutcheon shows that the more problematic aspect of Citizens United was the way it limited the basis on which Congress could regulate campaign spending: according to Citizens United, Congress’s only legitimate interest was avoiding what the Court called quid pro quo corruption—essentially, bribes—or the appearance of such corruption.

That part of Citizens United’s reasoning was not essential to the Court’s decision, but it has provided a powerful basis for further challenges to campaign finance law. In McCutcheon, Chief Justice Roberts, writing for the plurality, relied heavily on that principle in concluding that federal limits on overall campaign contributions are unconstitutional. That same rationale could well invalidate a host of other campaign finance limits—on soft money contributions, on corporate contributions, and even limits on individual contributions to particular candidates.

At issue in McCutcheon were so-called “aggregate” limits on the total amount individuals can donate to political candidates, parties, and PACs during an election cycle. These restrictions have been on the books since Congress passed them in 1974, and were upheld as constitutional in 1976, in the Court’s decision in Buckley v. Valeo. In that case, the Court reasoned that both contributions to candidates and independent expenditures are protected by the First Amendment. But it found that contributions are susceptible to regulation because they could allow a donor to directly influence a candidate and are a less direct form of First Amendment expression than independent expenditures.

Thus, the Court essentially forged a compromise, upholding limits on how much individuals could contribute to political candidates, but striking down limits on “independent expenditures,” that is, political campaign spending uncoordinated with the candidate. But the Court also foresaw the risk that contribution limits might be circumvented. So it upheld both base limits on how much individuals could give to any one candidate, and aggregate limits that set a ceiling on how much individuals could contribute overall. Otherwise, people might be able to donate large amounts of money to a wide range of candidates and committees, who could then transfer much of that money to particular candidates.

Advertisement

The Court has now overruled that aspect of Buckley. It found that developments in the law since Buckley have reduced the risk of circumvention, and that as long as individuals abide by the base limits on contributions to particular candidates, there will be no real risk of quid pro quo corruption from their donating to many candidates, parties, and PAC’s.

This reasoning is flawed on at least two levels. First, as Justice Stephen Breyer showed, in a strong dissent joined by Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan, there are in fact all sorts of technically lawful ways to circumvent the base limits if there are no restrictions on aggregate spending. Breyer provided a road map to the circumventers, identifying three ways (presumably among many more) in which rich donors could donate vast amounts of money to party committees and PACs that would then have the discretion to direct much of that money to particular candidates, thereby allowing donors to exceed existing limits on contributions to those particular candidates. Chief Justice Roberts responded that Congress could enact new restrictions to offset those risks, but the notion that this Congress will be able to pass anything in the way of campaign finance reform is entirely fanciful.

Second, and more fundamentally, why should the only interest that justifies limits on campaign finance be the avoidance of quid pro quo corruption and its appearance? To be sure, bribery is a problem, but that is not the only way that large amounts of money can threaten a democracy. If a handful of constituents can donate millions to a candidate and his party, while most others can realistically deliver only a vote and perhaps a small donation, then all constituents are not likely to be treated equally. Members of Congress spend a great deal of time raising the vast amounts of money they need these days to run a successful campaign, and if they do not pay more attention to those who can donate millions, they are not human, not exercising common sense, and not likely to be reelected.

In other words, even if no money is redirected and channeled to a particular candidate, and even if there is no bribery or quid pro quo corruption, there is a serious problem that warrants Congress’s attention. Why should those with more money have a greater say in who gets elected? And why isn’t Congress justified in restricting aggregate contributions to offset these negative effects on the democratic process? It is this aspect of the decision—the refusal to recognize any interest beyond quid pro quo corruption—that is likely to have the most damaging effect on campaign finance laws going forward.

Moreover, as Justice Breyer noted in dissent, the Court has previously ruled that Congress does have a compelling interest, not just in avoiding quid pro quo corruption, but in limiting wealthy donors’ “privileged access to and pernicious influence upon elected representatives.” In the 2003 case, McConnell v. FEC, the Court upheld limits on “soft money” contributions to political parties, despite the absence of any evidence that these donations—for such general purposes as voter registration and “get out the vote” efforts—had ever led to quid pro quo corruption. As the Court then stated, “Our cases have firmly established that Congress’ legitimate interest extends beyond preventing simple cash-for-votes corruption to curbing ‘undue influence on an officeholder’s judgment, and the appearance of such influence.’” That principle no longer holds, and as a result much of campaign finance law is in jeopardy.

Citizens United is one of the Court’s most unpopular decisions, and Chief Justice Roberts seemed to acknowledge this in McCutcheon, opening his opinion with a defense of the Court’s duty:

Money in politics may at times seem repugnant to some, but so too does much of what the First Amendment vigorously protects. If the First Amendment protects flag burning, funeral protests, and Nazi parades—despite the profound offense such spectacles cause—it surely protects political campaign speech despite popular opposition.

But campaign finance regulation is categorically different from efforts to silence flag burners and Nazis. The reason legislators sought to ban flag burning and Nazi parades is that the majority found such speech repugnant; it was offended by the content of these individuals’ minority beliefs. Legislation designed to limit the distorting effects of wealth on elections, by contrast, is not driven by repugnance, nor is it aimed at any particular point of view. It limits the influence of George Soros and Sheldon Adelson alike. Indeed, it limits the influence of all of us equally, regardless of our political perspectives. Campaign finance reform is motivated by concern that a democracy that is for sale to the highest bidder is no longer a meaningful democracy.

Advertisement

This doesn’t mean that campaign finance laws should be free of First Amendment scrutiny. Political speech costs money, and efforts to limit contributions and expenditures for political campaigns deserve careful scrutiny. There are real risks that some kinds of limits could shield an incumbent, who already has advantages of running from office, from an effective challenger. The problem with the Roberts Court’s approach is not that it demands good reasons for campaign finance laws. It is that it has excluded as a good reason the concern that unlimited money will undermine the very foundational principle of democracy; namely, that all should have an equal voice in the electoral process. Why is that not a compelling interest that justifies barring millionaires from exploiting their wealth to buy political influence?