It is right, but also not quite right, to celebrate the journalist and contemporary historian, Svetlana Alexievich, this year’s laureate of the Nobel Prize in Literature, as a Belarusian writer. The force of her work, the source of its power and plausibility, is the choice of a generation (her own) as a major subject and the close attention to its major inflection point, which was the end of the Soviet Union. She is connected to Russia and Ukraine as well as Belarus and is a writer of all three nations; the passage from Soviet state to national state was experienced by them all, and her life has been divided among them. Her method is the close interrogation of the past through the collection of individual voices; patient in overcoming cliché, attentive to the unexpected, and restrained in the exposition, her writing reaches those far beyond her own experiences and preoccupations, far beyond her generation, and far beyond the lands of the former Soviet Union. Polish has a nice term for this approach, literatura faktu, “the literature of fact.” Her central attainment, the recovery of experience from myth, has made her an acute critic of the nostalgic dictatorships in Belarus and Russia.

To say that Alexievich was born in Soviet Ukraine in 1948 is already to indulge in the kind of simplification she has sought to expose from the beginning. Her home city, Stanislaviv, was in a region known as Galicia, which had been part of Poland from the fourteenth century, part of the Habsburg monarchy in the nineteenth, and part of the Second Polish Republic in the 1920s and 1930s. It fell under Soviet rule in 1939 when the Soviet Union invaded Poland following the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, and then under German power in 1941 when Hitler betrayed Stalin and invaded the Soviet Union. Jews were the largest population in Stanislaviv before the war; almost every single one was murdered in the Holocaust. Many of the city’s Poles and Ukrainians were killed or deported by either the Germans or the Soviets during the war, and others were drafted into service in the Red Army and died in combat. The Stanislaviv where Alexievich spent the first few years of her life was thus a new Soviet city, both in its administration and its population.

Perhaps it mattered that essentially everything about the city of her birth was a suppression but also an invocation of an unremembered past, and that her family was involved on both sides in disputes that could never be fully articulated. Her Belarusian father had fought against Ukrainian nationalists who were trying to win Galicia for an independent Ukraine. Her Ukrainian maternal grandmother told her about what Ukrainians call the “Holodomor,” Stalin’s political famine, which had killed more than three million people in Soviet Ukraine in 1932 and 1933. That was crucial knowledge, because the collectivization of agriculture, whose purported success was a central myth of Soviet history, was one of the causes of the famine. Ukrainians were blamed for the misery and subjected to harsh requisitions and reprisals that channeled starvation on to their territory, whereas Soviet citizens as a whole were told that collectivization was a grand success hindered only by nationalists and saboteurs.

It was collectivization, along with World War II (known as the “Great Fatherland War”), that created the Soviet Union that people of Alexievich’s generation experienced. Both were calamities that were covered in beautiful myths, myths that worked in part because people wanted individual suffering and death to have meaning. Collectivization was said, in retrospect, to have been necessary for victory in war, and victory in war was taken to demonstrate the legitimacy of the system as such. Collectivization was the founding stone of a new kind of society, which after the war could be brought to new places such as Stanislaviv. Alexievich’s family moved from Stanislaviv in Soviet Ukraine to the Polesian region of southern Belarus in the 1950s, a land known for the ambiguous national identity of its inhabitants. As a very young woman Alexievich taught school and worked at a local newspaper in these provinces; in the late 1960s, she went to Minsk, the capital of Soviet Belarus, to study journalism, but returned again to the provinces when she finished, working in Biaroza in the southwest, in another town that had been in Poland before the war. In the meantime, the name of her hometown, Stanislaviv, was changed to the one it still bears now, in independent Ukraine: Ivano-Frankivsk.

Three constitutive elements of the Soviet identity of Alexievich’s generation were movement from one part of the USSR to another, the Russian language that made such movement possible, and the official Soviet nostalgia that slowly replaced Marxist ideology in the 1970s. Leaving Soviet Ukraine for Soviet Belarus, as her family did, would have made an overall Soviet loyalty more plausible than any local one; although neither of her parents was Russian by origin, Russian was the language of the family, and the only language in which Alexievich has published. People of her generation, such as Russian President Vladimir Putin (born in 1952) and Belarus President Alexander Lukashenko (born in 1954), did not take part in the great transformations and cataclysms of the 1930s and 1940s, but were nourished on the quasi-Marxist idea that all the suffering had a purpose, and the neo-provincial idea that this purpose was the continuation of the exemplary Soviet state in which they happened to have been born. When Leonid Brezhnev proclaimed that the Soviet Union exemplified “really existing socialism,” he deprived the future of its utopia, insisted on the adequacy of the present, and thereby located the legitimacy of the system in its past. When we confront, today, the myth of the Great Fatherland War and of Stalin as a good manager, we are hearing not the echoes of the events themselves, but of the memory campaign of the 1970s. The generation that grew up in this era is today in power in Russia and in Belarus—although no longer in Ukraine.

Advertisement

What was unusual about Alexievich as a Soviet journalist in the 1970s and early 1980s, in Biaroza and then in Minsk, is that she sought to halt the Soviet time machine as it switched gears from forward to reverse. What was almost unique was that she found a way to do so: an investigative journalism that began from the assumption that truth was accessible but that its excavation was a matter of hard individual work with an interlocutor who was probably already yielding the past of his or her own life to the collective Soviet story. Her first manuscript, which could not be published, was about the archetypical Soviet experience of leaving the village for the city, the basic form of social advance which also meant, in the Soviet Union as of course everywhere, the exchange of local memories for the rougher tropes of urban life.

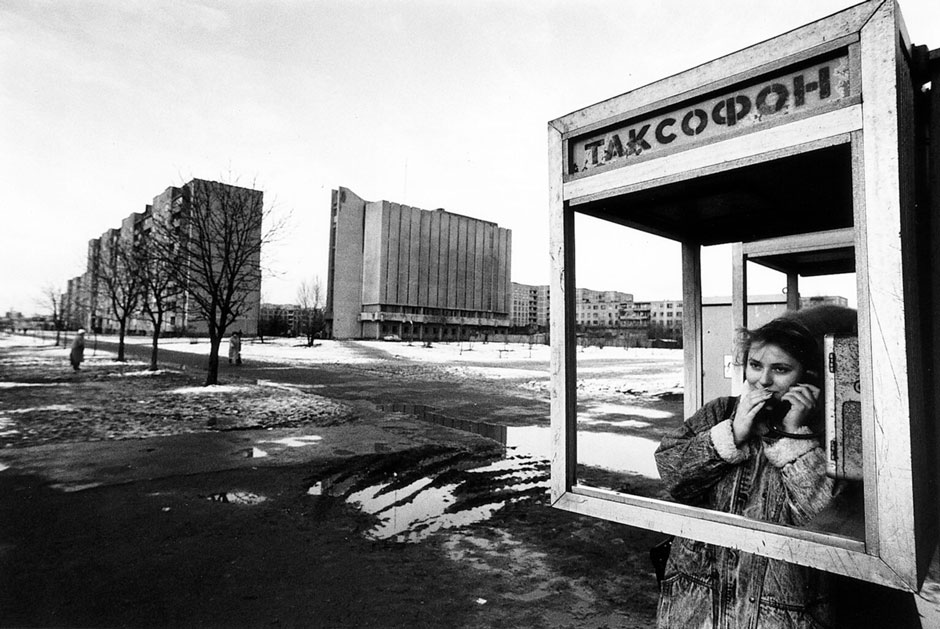

In the towns of the western Soviet Union that Alexievich knew best, urban life was not simply a novelty for some, but a novelty for almost everyone, since prewar urban classes had been destroyed by war, Holocaust, and deportation. Empty cities were settled by new people, not only from the local countryside, but from throughout the USSR. Minsk, the capital of Soviet Belarus, was perhaps the extreme of a postwar city of the Soviet Union, having lost under German occupation, not only its large Jewish population, but a significant fraction of the Belarusian-speaking hinterland. Alexievich herself, working in Minsk for a Belarusian cultural journal that was published in the Russian language, was taking part in the linguistic russification of the region that was enabled by the war. Minsk was (and remains) a capital of Soviet nostalgia, where the straw of wartime suffering is spun into the gold of political meaning. No Soviet republic suffered more from the war than Belarus, and its partisans and its “hero cities” became the loci of the cult of remembrance.

This process was early on challenged by the outstanding Belarusian writer Ales Adamovich, whose novel Khatyn (1971) began with an acceptable subject—the village of Khatyn, which had been selected for official commemoration of the Soviet partisan war against the German occupation of Belarus. But it immediately turned into a quite challenging retelling of the very events that were being monumentalized. The story begins with the narrator on a bus ride to Khatyn; blinded during combat, he can now only hear the voices of his former comrades, which call forth memories of war as it was. Although Khatyn was a work of fiction and Alexievich was a journalist, the method of closing one’s eyes to monument and listening to voices until the ruins underneath begin to move was the one that she made her own. Adamovich, whose novel is now available in an excellent English translation, was a major literary and intellectual influence upon Alexievich.

Alexievich’s second book, completed in 1983, was about the experiences of Soviet women soldiers in World War II, whom she traveled the Soviet Union to meet, without support from her employers at the cultural journal in Minsk, on her own time and at her own expense. This book too could not be published. But in 1985 came perestroika, the reform program of Mikhail Gorbachev, and with it the ability to publish about the past. Her book was published under the title War’s Unwomanly Face, and sold extremely well in the last years of the USSR. Even after thirty years of gender studies in Europe and the United States it remains a landmark in the study of female soldiers.

Advertisement

The end of the Soviet Union did not much change Alexievich’s subjects, nor indeed her political position. It is not quite right to speak of her as a dissident or an oppositionist, since she was not really politically active, either in the late Soviet Union or in the independent Belarus that succeeded it in 1991. Instead she began to write about the experiences of the 1970s and 1980s, those of her own generation, resisting both the official interpretations (and silences) of the time as well as the attempts of nationalists (whether Belarusian, Russian, or any other) to use the Soviet past as the raw material for another story about a bright future.

Alexievich’s fourth book, published in 1989, was about the Soviet war in Afghanistan (1979-1989), the disaster that perhaps more than anything brought down the Soviet Union. At first the Soviet press was silent about the presence of the Red Army in Afghanistan, then portraying the mission as one of keeping peace rather than supporting a particular (and doomed) regime. In an age of television, the typical Soviet press image was of a soldier planting a tree. Alexievich once again sought out veterans and the women, the young soldiers and their mothers. The result was a masterpiece of reportage, probably her best book, in which the problems (what we might now call post-traumatic stress) of the young men emerge through the words of their mothers as well as their own, and then the typical experiences slowly emerge through the individual memories. The book was published in English as Zinky Boys, which is awkward; the “zinc” is a reference to the coffins of soldiers.

For Alexievich, the end of the Soviet Union in 1991 was not a radical new beginning, since, she seemed to be saying, the present cannot move into the past when the normal process of considering the past has been disrupted. When official nostalgia has filled the space needed for individual reconsideration, change can be literally fatal. Alexievich’s next book was about people of her parents’ generation, often heroes of the Second World War II, who committed suicide in the 1990s.

In the following book, about the nuclear disaster at Chernobyl, she brought together her technique of registering voices with a more explicit allegory about the meaning of the Soviet past. On the one hand, she more than anyone else made the victims into distinct individuals surrounded by a particular Soviet context, making sense of what happened in haste the best they could with the references they had:

They told us a bunch of nonsense. You’ll die. You need to leave. Evacuate. People got scared. They got filled up with fear. At night people started packing up their things. I also got my clothes, folded them up. My red badges for my honest labor, and my lucky kopeika that I had. Such sadness! It filled my heart. Let me be struck down right here if I’m lying. And then I hear about how the soldiers were evacuating one village, and this old man and woman stayed. Until then, when people were roused up and put on buses, they’d take their cow and go into the forest. They’d wait there. Like during the war, when they were burning down the villages. Why would our soldiers chase us?

At the same time, the subject of radiation poisoning made Alexievich’s specific approach to past, present, and future painfully explicit. When the reactor at Chernobyl exploded in April 1986, Soviet authorities were very slow to inform the local populations and were never clear about the scale of the disaster. Inhabitants of Soviet Ukraine were affected first, but the entirety of Soviet Belarus soon fell under the cloud of radiation. That Soviet authorities chose silence meant that the harm was all the more durable. Once exposed to radiation, there was little that people could do. The combination of disaster and mendacity was illness and death.

One way to consider Alexievich’s successive investigations of durable catastrophes is to contrast them with some of the shortcuts of a popular and kindred genre, the post-catastrophist fiction of the former Soviet space and around the world. In the United States the literary type is familiar from such works as David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest (1996), in which North America has been transformed by an insanely ambitious attempt to reverse pollution; and Gary Shteyngart’s Super Sad True Love Story (2011), in which the backdrop is the collapse of the United States under Chinese debt. Haruki Murakami, whose name often arises in conversations about the Nobel Prize, frequently asks the reader to assemble clues about the true nature of a future calamity. A striking Russian variant is Mikhail Yuriev’s The Third Empire: The Russia that Ought to Be (2006), in which a global war brings Russian power to the shores of the Atlantic. What is common to the American and Russian examples of the genre is that they offer a form of consolation: either the gentle one of comedy, or the fiercer one of power. People find solace in the drugs and love in Wallace and Shteyngart and Murakami, and exult in power reading Yuriev.

In Belarus, the gifted Victor Martinovich offers catastrophe without either of these consolations: in Mova 墨瓦 (2014), he imagines a future Belarus that is part of Russia which is itself enclosed by a Chinese empire. In this realm the legitimate form of public activity is shopping and the permitted local language is Russian. There is no comic relief, indeed not much relief at all. Power brings no redemption to the provinces. The object of addiction are scraps of paper with words in Belarusian—mova is the Belarusian word for “language.” If we get as far as this fictional Belarusian perspective on post-catastrophe, we approach Alexievich from another side. In her work there is no redemption from catastrophe because it is behind us and within us. The search for bits of the authentic past is individual and dangerous and disruptive, but there is nothing else to be done. Some of Alexieivich’s critics in Belarus today wish she would use the Belarusian language, seeing in the national culture a crucial missing element of authenticity, or an opportunity to create something fresh. It is interesting, for example, that Martinovich wrote his first novel in Russian but his second in Belarusian.

Alexievich’s sad chronicles—about women soldiers in World War II, veterans of the Soviet war in Afghanistan, victims of the Chernobyl disaster, among other subjects—are thus the opposite of escapism. She does not allow herself to jump ahead with the toolkit of fiction and then look back for meaning, redemption, or distraction. She instead rescues the recent past from the patterns of collective forgetting by the hard work of speaking to thousands of people, and then arranging their voices in a way that rescues experience without imposing narrative. Alexievich is sometimes compared to Ryszard Kapuściński, the great Polish international journalist. But unlike him she resists the charms of constructing appealing characters from composites. She has no characters; only voices.

Alexievich is one of very few winners of the Nobel Prize for Literature associated primarily with non-fiction, a tiny group that includes Alexander Solzhenitsyn, Winston Churchill, and the German historian Theodor Mommsen. That juxtaposition reveals a crucial difference: whether writing of the Roman Empire (Mommsen), World War II (Churchill), or the Gulag (Solzhenitsyn), the three men in question were striving for coherent master interpretations of major historical events. By contrast Alexievich might seem less ambitious, in that she seeks not to give shape to any one event. But what she has done, and here of the three she is closest to the younger Solzhenitsyn, is to work indirectly against an overweening master narrative that already exists. Unlike Solzhenitsyn, however, who sought to recapitulate all of Soviet history in later life, Alexievich has remained close to the experiences and memories of her own generation, which by their nature are constantly changing.

In her most recent work Alexievich identifies explicitly (“we”) with her own generation, simultaneously Soviet and post-Soviet. In Second-Hand Time, composed during a decade in political exile and published shortly after her return to Belarus in 2013, she treats the Soviet personality as a subject in and of itself, open to interpretation and reinterpretation, to be sure, but not admitting of any new beginning. This work is perhaps more open to criticism than previous books, since Alexievich’s method depends upon direct contact with her sources, and in emigration she might not have been able to see the variety of ways Belarusians and others confronted the past in the 2000s, when she was abroad. That said, it is precisely Alexievich’s relentlessly consistent interrogation of the formative experiences of the 1970s and 1980s that made hers such a precise critique of the abuse of memory in contemporary Belarus and especially contemporary Russia. Her non-fiction works as a kind of anti-fiction, and alternative to the alternative realities which, in both Russia and Belarus, arise behind the blindfold of a double nostalgia: of today’s ruling elite for the 1970s and 1980s, which were themselves a time of manufactured nostalgia for the Soviet 1930s and 1940s.

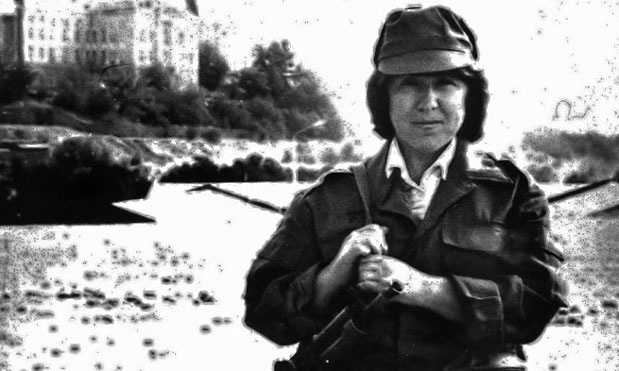

It is in this light that Alexievich’s criticism of the current Russian war in Ukraine should be understood. It would be easy enough to place her in the tradition of courageous Russian investigative reporters, many of them female, some of these assassinated, who resisted the narrative of Russia’s wars under Putin by writing what they saw. One of the most impressive of these, Anna Politkovskaya, was murdered on October 7, 2006; the ninth anniversary of her death was the day before Alexievich was awarded the Nobel Prize. But since Alexievich made it her life’s work to replace the mythmaking of the 1970s and 1980s with a kind of investigative contemporary history, she also brings to bear a more fundamental critique of wars that are grounded in invented historical tropes. What we experience in the west as Russian propaganda is in part an earnest claim that past war ennobles current war and justifies future war. When the Great Patriotic War is seen as a faultlessly virtuous victory rather than the bloodiest struggle in human history, war can seem more inviting and virtuous; when the dreadful and lost war in Afghanistan is blurred into a narrative of unmanly Soviet weakness, the real suffering of veterans seems irrelevant; when Chernobyl is repressed in official memory it becomes possible to speak on Russian television about turning countries to radioactive ash. Alexievich reacted quickly, instinctively, to all of this; and paid a price.

Alexievich has been unremembered in the country, Russia, where her work has perhaps the most contemporary relevance. She writes only in Russian and her themes are those with which Russians, at least of her generation, could in principle identify. Her book on women in war sold two million copies in the Soviet Union, which suggests that it should now rest on a million or so bookshelves in Russia. This summer she was subjected to a press campaign in Russian media in which she was branded as “anti-Russian.” The reason given for this claim was her criticism of Russia’s war in Ukraine. Here Alexievich’s response was revealing. Standing on the Maidan, she said, she looked at the photographs of the men who were killed by snipers during the Ukrainian revolution. This, the site of the Ukrainian revolution of 2013-2014, brought tears to her eyes. Weeping at the fate of others, she said, “is not hatred.” And then: “It is hard to be an honest person in our times.”

But for Alexievich, after her return to Minsk two years ago, it has certainly been easier than for others. She had no trouble explaining to westerners, far more quickly than they themselves could usually grasp, that Russia had in fact invaded Ukraine. She also very quickly explained that the fault lay not with one man but with the experiences of Soviet generations, now reworked for new wars. When she listed the fake descriptions of events in Ukraine in the Russian media, she spoke of Russian society as a “collective Putin.” As she put it, “Putin placed his bet on the basest instincts and won. Even if he disappeared tomorrow, we would remain as we are.”

“We” is the telling word, since Alexievich, when speaking of Russians, might just as easily say “they.” But she does not. She clearly identifies with Russians as well as with Belarusians and Ukrainians, as the three new nations move through the uncharted difficulties of sovereignty. The fact that today not only Ukrainians but also Belarusians belong to an unmistakably different political society than Russians does not mean that they have been separated from Soviet history, since, suggests Alexievich, no such separation is actually possible. Sometimes she sounds optimistic and sometimes less so. She makes clear that generational turnover does not automatically bring change; speaking of travels through contemporary Belarus, Ukraine, and Russia, she finds “rather servile” young people. But she also seems to regard the Ukrainian revolution as a rupture, and imagines for Belarus the possibility of becoming a “normal European country.” Russia, she says, has a problem with “nationalism”; perhaps that, too, can be overcome. One must again remember that all of these writings, and all of these statements, are in the Russian language.

What would a Russian world be like without nationalism? One of the Kremlin’s justifications of the present war in Ukraine was the idea of defending a “Russian world.” In the understanding of this phrase promoted by Putin and the Russian leadership, the “Russian world” is a specific place where people speak Russian, and therefore deserve protection by the Russian army. This version of a “Russian world” is inherently totalitarian, since it confuses individual linguistic practices with causes de guerre and allows leaders thousands of miles away to decide who requires their protection.

Yet the idea of a “Russian world,” of an international exchange of ideas in the Russian language, does of course make another kind of sense, just as an “English world” or a “Spanish world” or a “Chinese world” might. The “Russian world” can also be, as Alexievich has said, universal and “humanistic.” In this sense she is certainly a Russian writer, as well as a Belarusian writer, and a writer of Ukrainian origin. If the Russian language is not simply a source of ethnic provincialism but a means of universalism, her “we” (spoken in Russian) is a larger one than those who remember the Soviet Union and speak the Russian language.

Indeed, her Nobel Prize will expand the Russian world of letters, since her prose is accessible not only to those who share her background and concerns but to younger people who can learn from her what the Soviet Union was and what its legacy means. As a Ukrainian university instructor in Texas put it, reacting to the news about the Nobel: “my students do not weep when they read Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago, but when they read Alexievich’s Voices from Chernobyl—then they do.”