The term “outsider art” was coined in 1972 by the British art historian Roger Cardinal as a way to categorize work that might otherwise be described as naïve, fanatical, eccentric, autistic, or insane. The Los Angeles artist Jim Shaw is a connoisseur and collector of such things—he’s an esoteric populist who doesn’t only make art but, since he began exhibiting found “thrift store paintings” in 1991, has created his own tradition, an American vernacular surrealism that might be termed “crackpot gothic.”

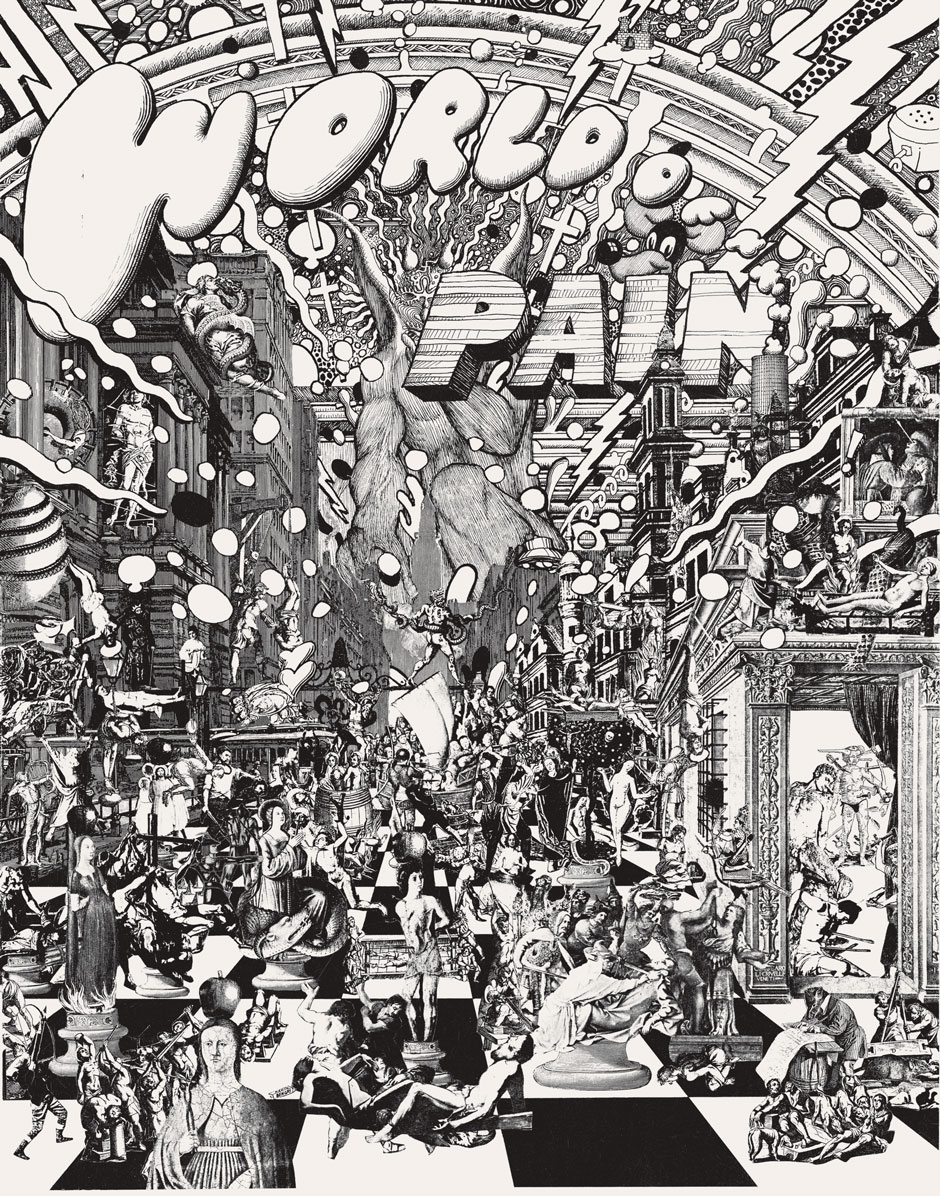

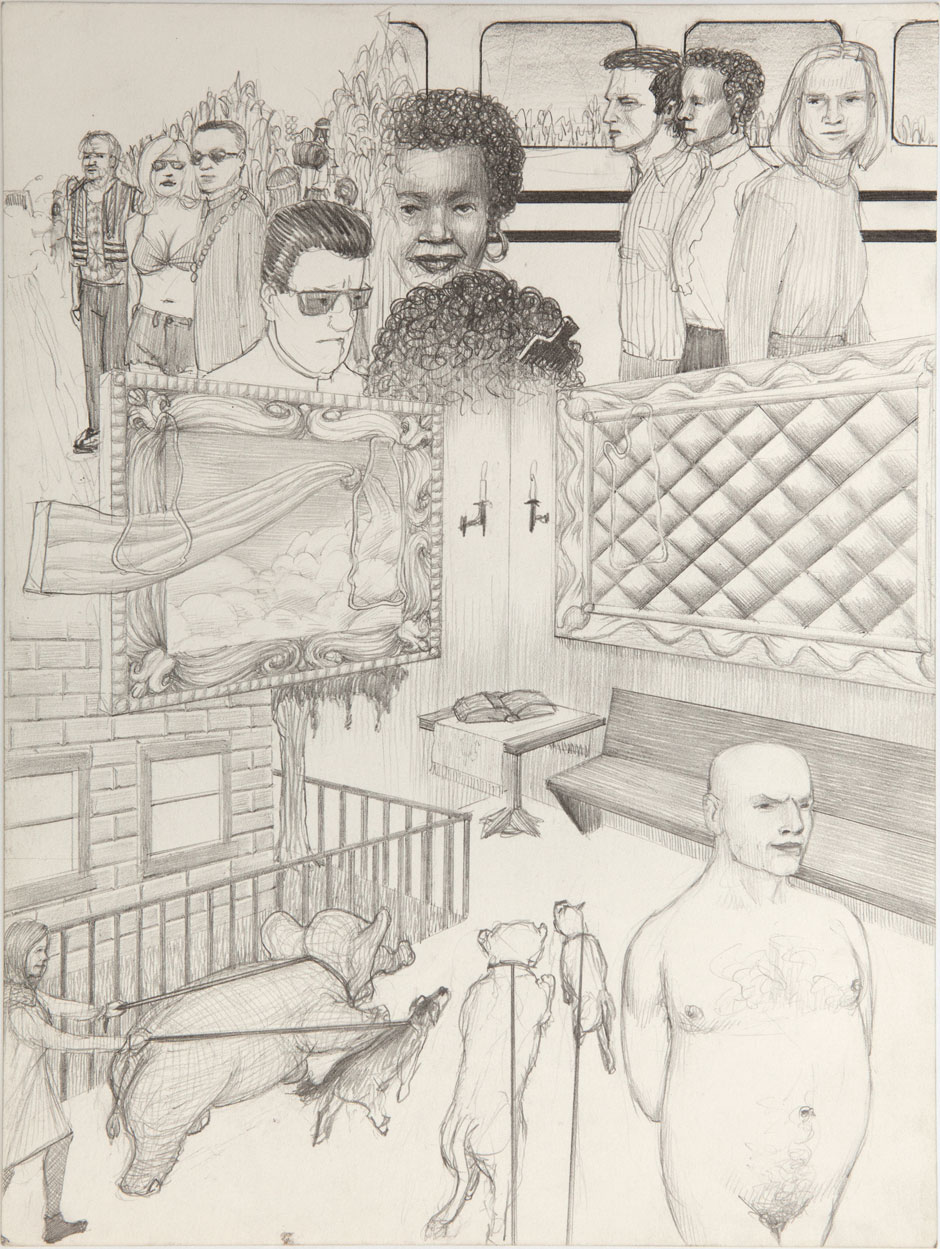

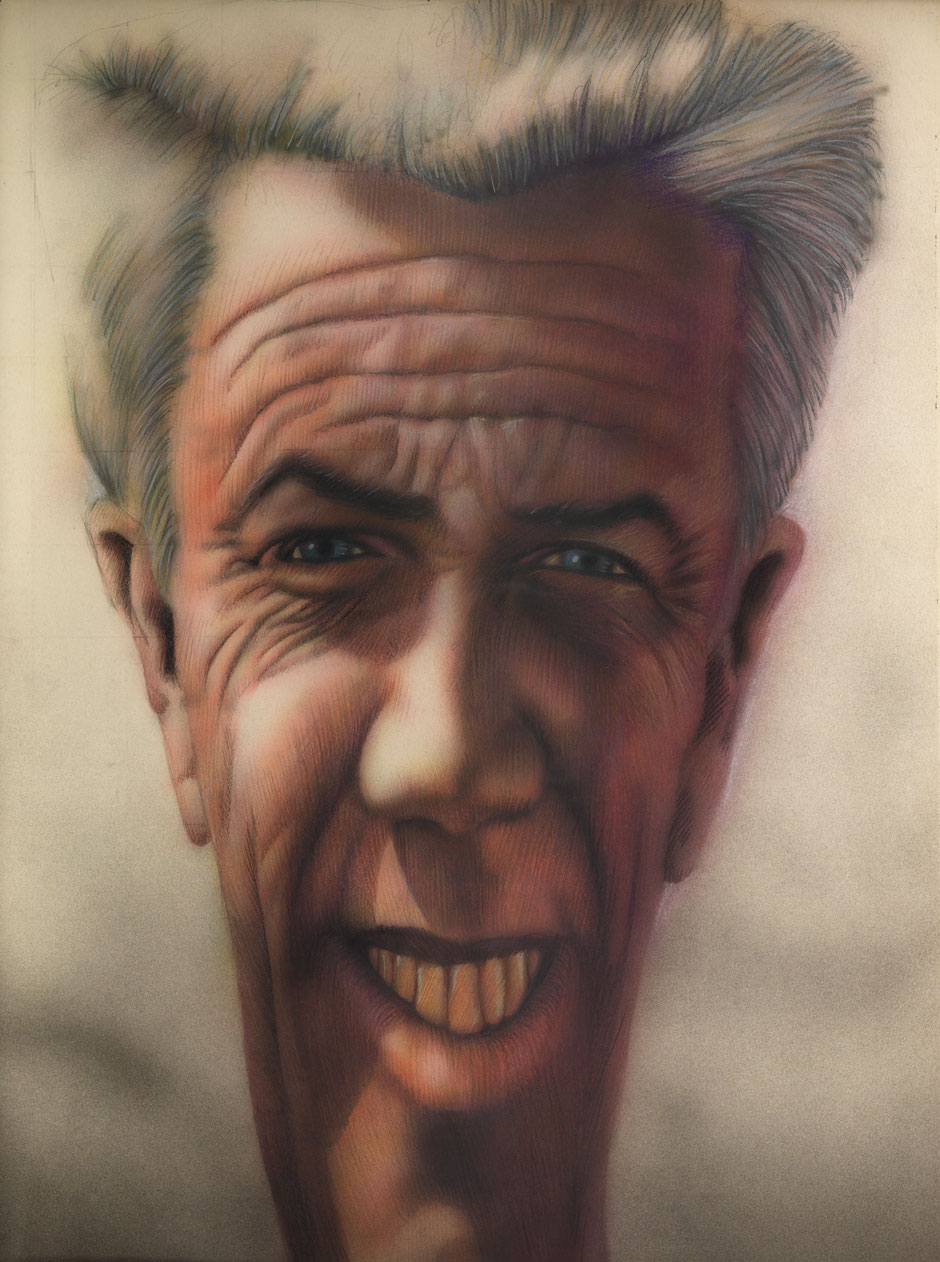

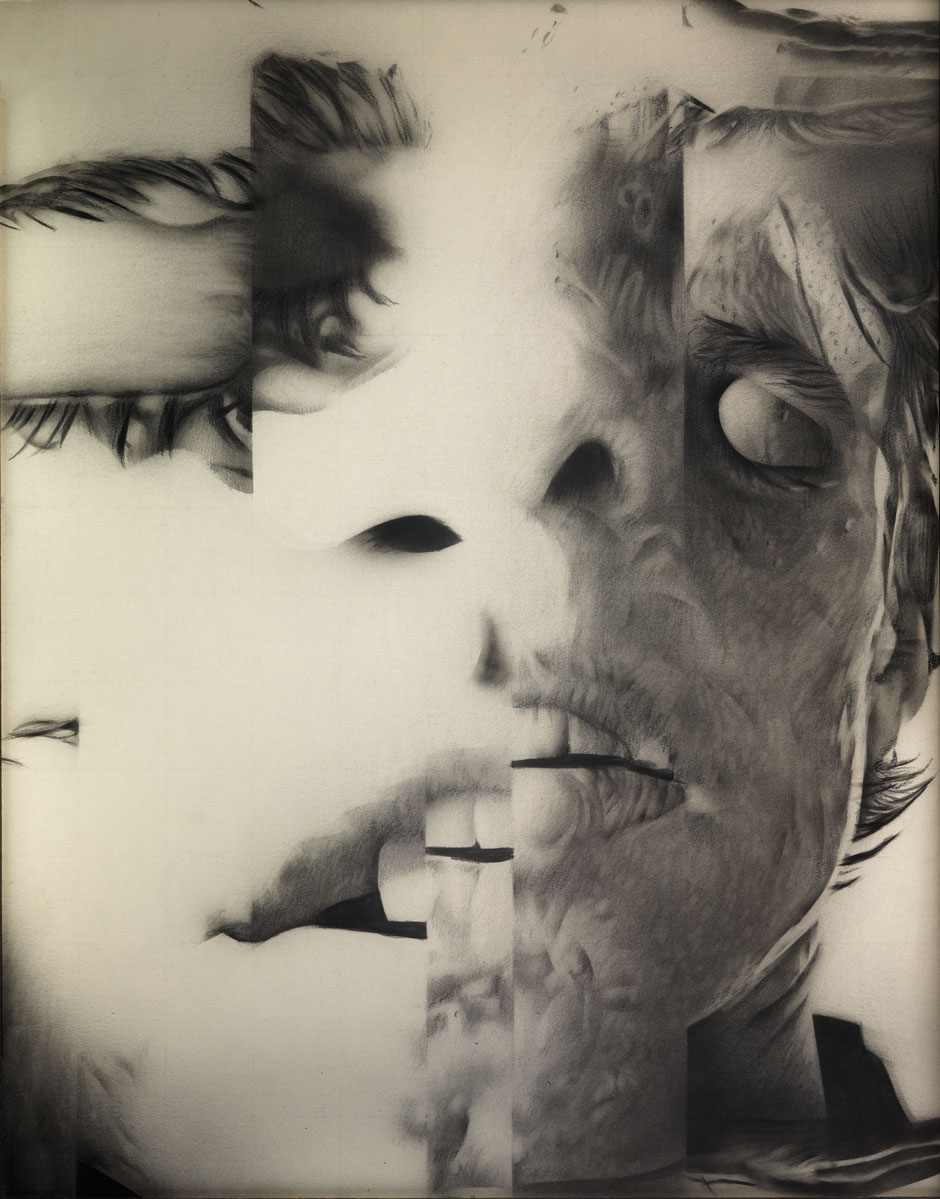

“The End is Here,” which is the sixty-three-year-old artist’s first American retrospective, occupies three floors at the New Museum. The first floor is mainly devoted to Shaw’s paintings and drawings, which range from crude psychedelic mandalas and parodies of Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights to fastidious sketches of imaginary insects and distorted portraits of celebrities like Clint Eastwood.

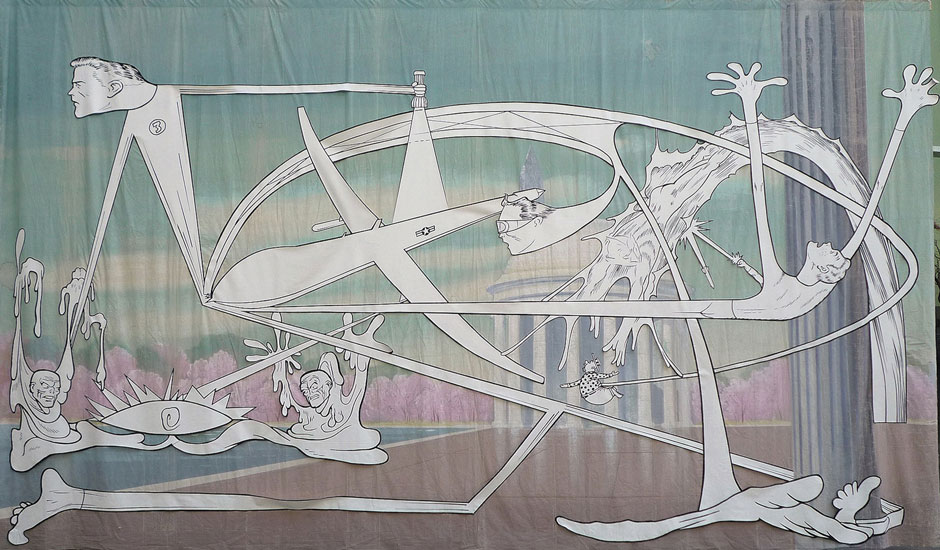

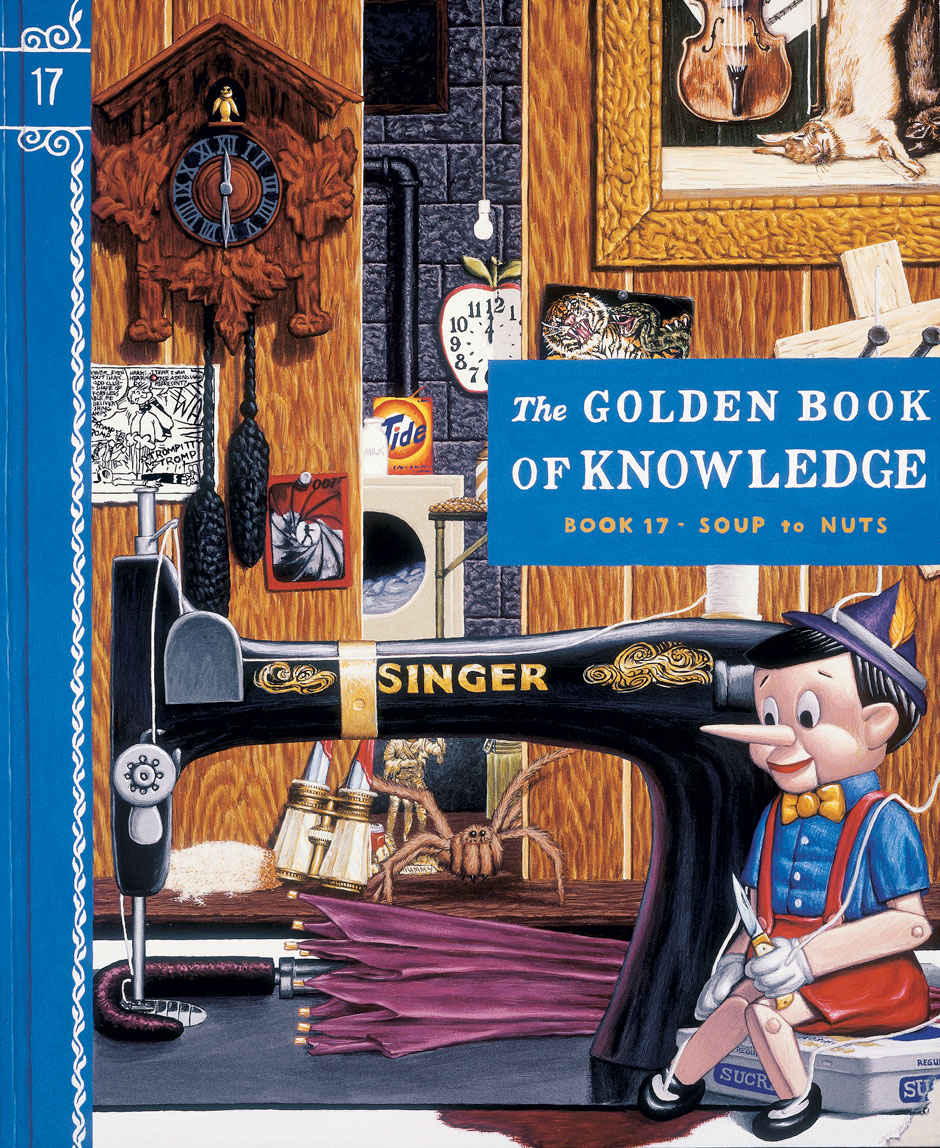

The third floor features larger works—including muslin banners that, among other things, use the 1950s comic book character Plastic Man to suggest Picasso’s “Guernica,” and large free-standing pieces, full of discordant cartoon creatures and political caricatures, including a ski-nosed Richard Nixon, that have been fashioned from old wooden theatrical flats. As if to showcase the source of Shaw’s inspiration, and maybe aspiration, the middle floor shows samples from his extensive collection of anonymous, amateur paintings—many of which he found in thrift stores—as well as magazines devoted to UFOs and the Kennedy assassination, and all manner of millennial religious cult paraphernalia (pamphlets, handbills, and LP covers).

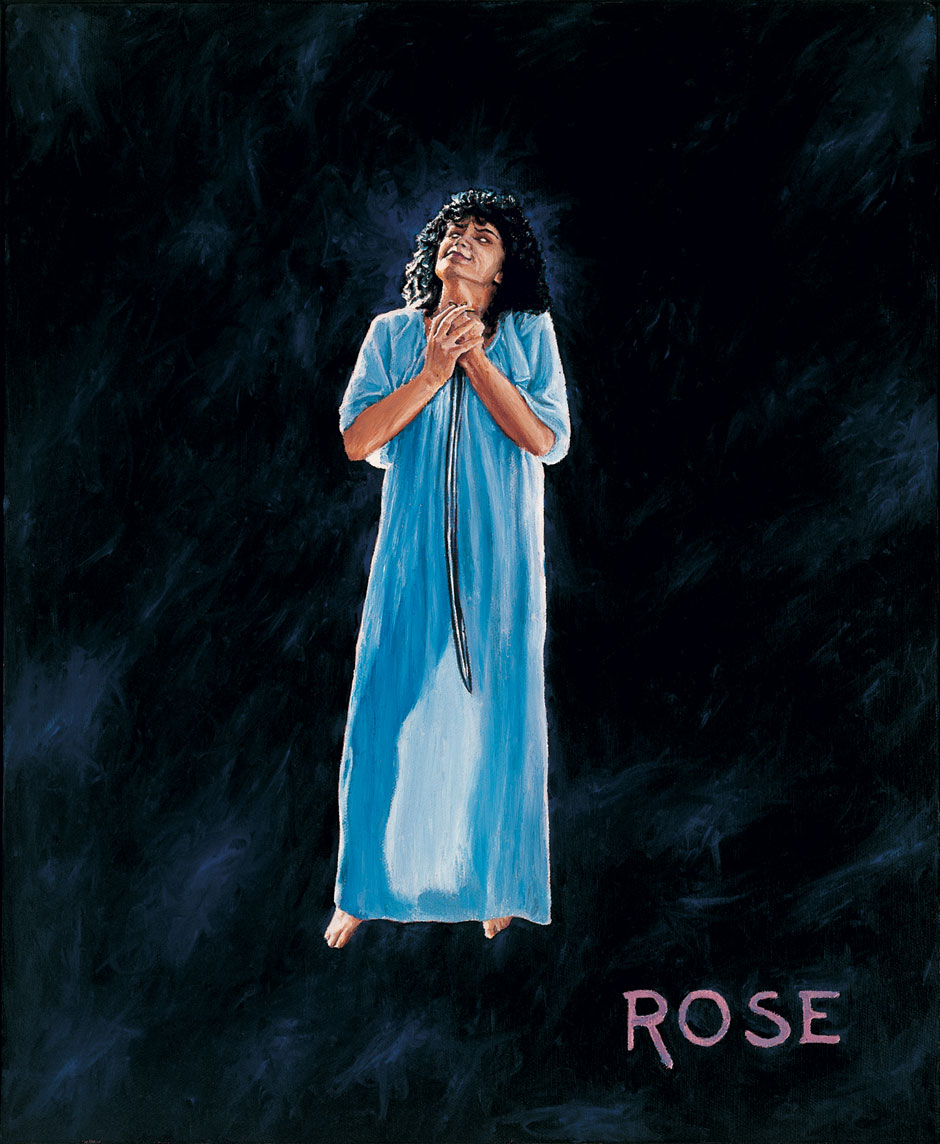

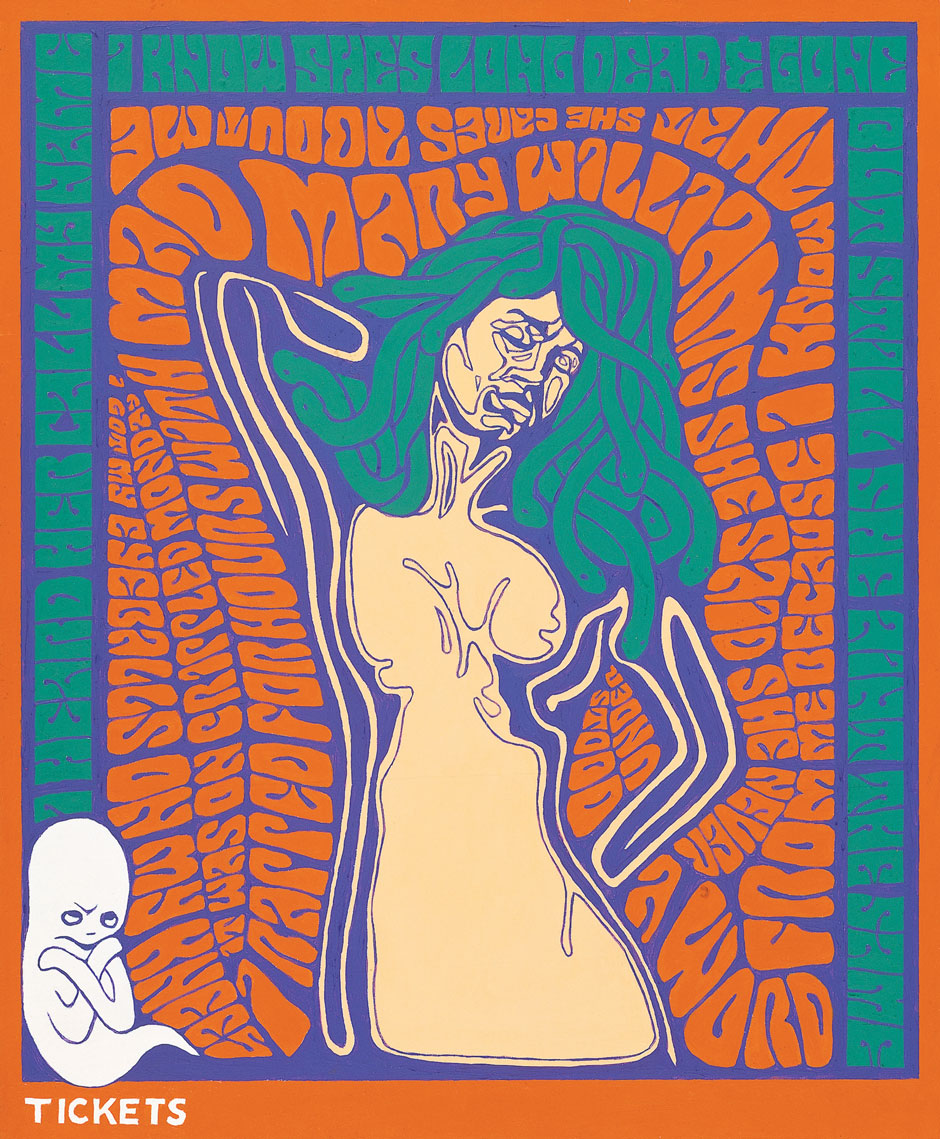

“The Hidden World,” as Shaw calls this collection, recently filled three floors of an appropriately dingy abandoned schoolhouse on rue de l’Hôpital Saint-Louis in Paris, where Shaw is greatly admired, perhaps for his exoticism. In addition to found objects, “The Hidden World” as installed at the New Museum incorporates some fetish objects Shaw fashioned for his own invented religion, O-ism, which, he claims, originated, like Mormonism, in mid-nineteenth century upstate New York. Its beliefs, according to Shaw, include “the notion of a female deity, of time going backwards, of spiritual transience, and a prohibition on figurative art”—although this prohibition, to judge from a video, does not extend to dancing chorines.

Shaw is often associated with the late Mike Kelley. Both men grew up in suburban Michigan, attended Cal Arts, and together with several other artists formed a post-punk noise band, Destroy All Monsters. Both were drawn to junk material, outlandish pop culture mash-ups and the geeky detritus of their 1960s adolescence. Kelley worked in many mediums, including video, performance, and installation, with a sprawling oeuvre that leaked autobiography; Shaw has a narrower focus and, at least as presented by the New Museum, which emphasizes his graphic works, is more oriented toward the production of art objects. Both artists cultivated punk attitudes, but where Kelley tended toward a bilious black humor, Shaw is more prankish.

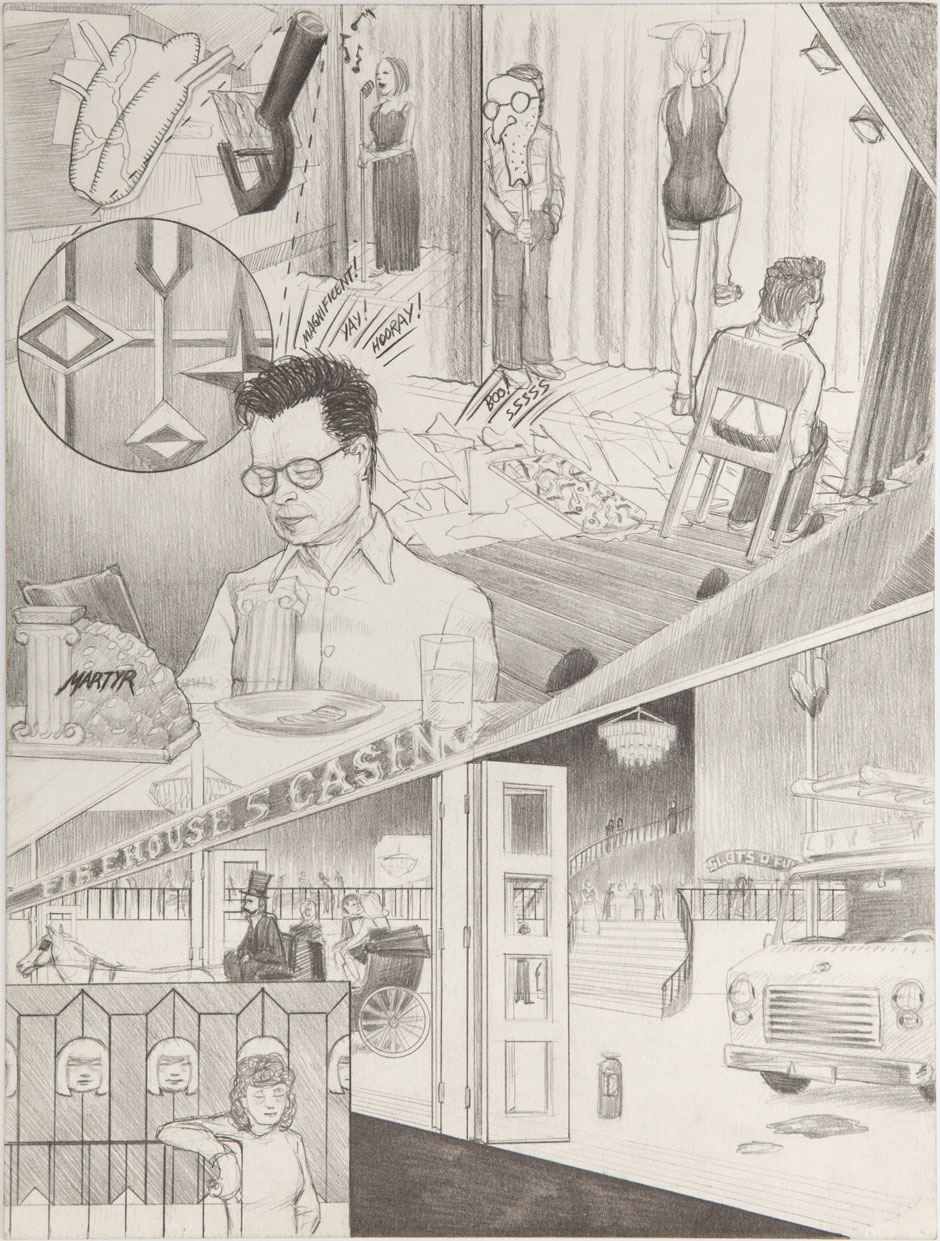

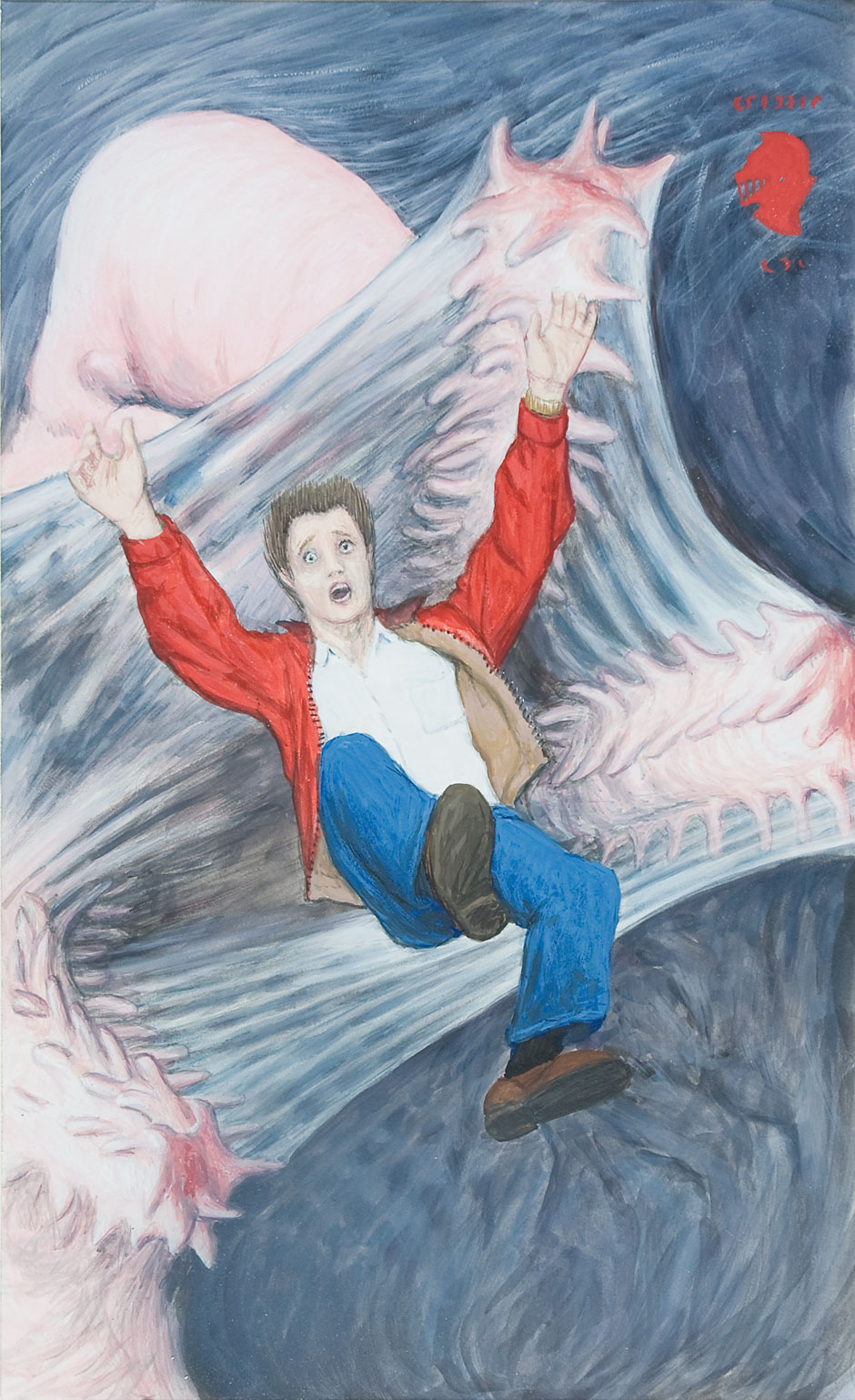

Like the surrealist Max Ernst, Shaw eschews a single signature style in favor of an elaborate, somewhat hermetic personal mythology. (What prompted the artist to make a drawing based on ten grimacing images of the 1940s big band leader Kay Kyser?) While skewing outré, Shaw is essentially a collagist, as was Ernst, and his eclectic influences include not just DC comic books (a frequent subject) treated as mass-produced illuminated manuscripts and underground comix, but Salvador Dalí, Peter Saul, and Otto Dix, as well as Bruegel, Fra Angelico and the illustrations found in medical textbooks. Shaw’s affinities with surrealism are most apparent in his “Dream Objects,” many of which are covers for non-existent paperback books, as well as the baroquely sexual, often hilarious “Dream Drawings” that purport to document his nocturnal adventures.

Advertisement

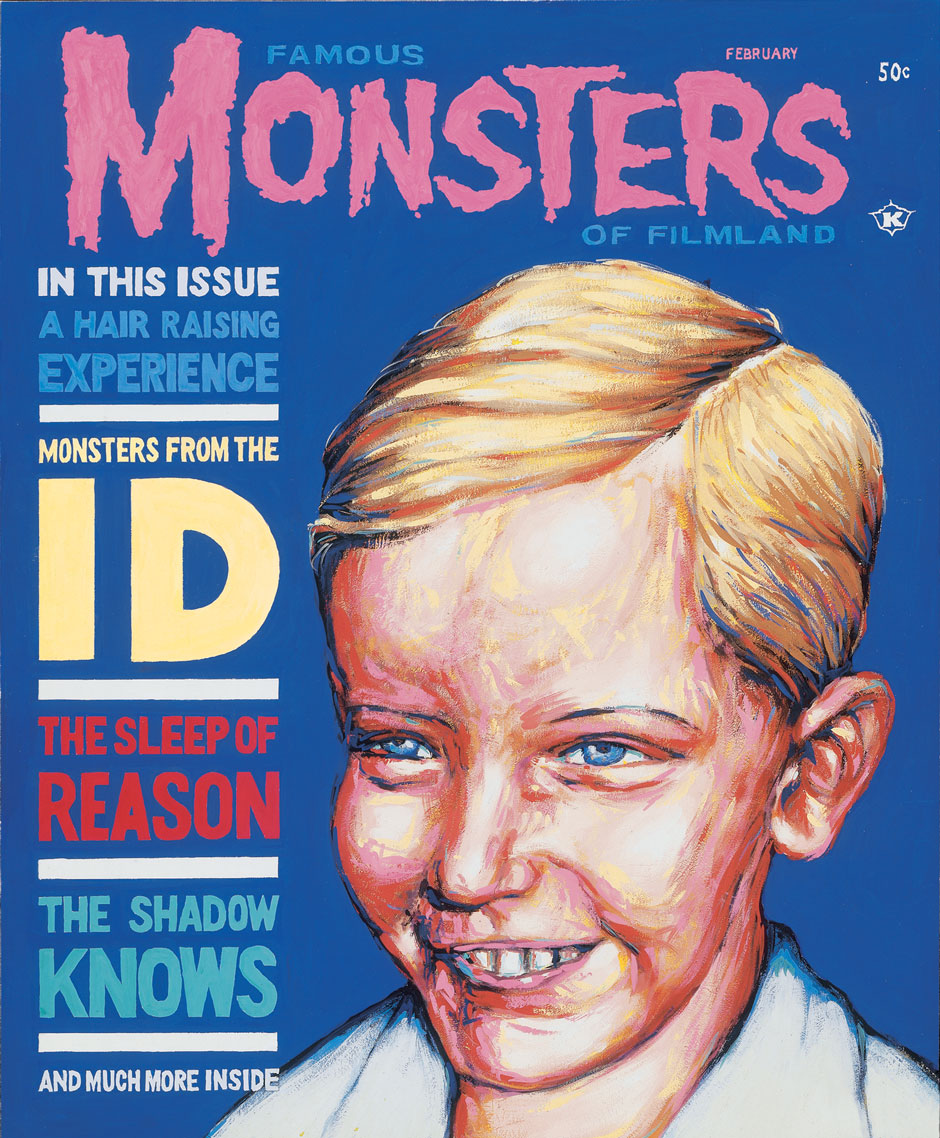

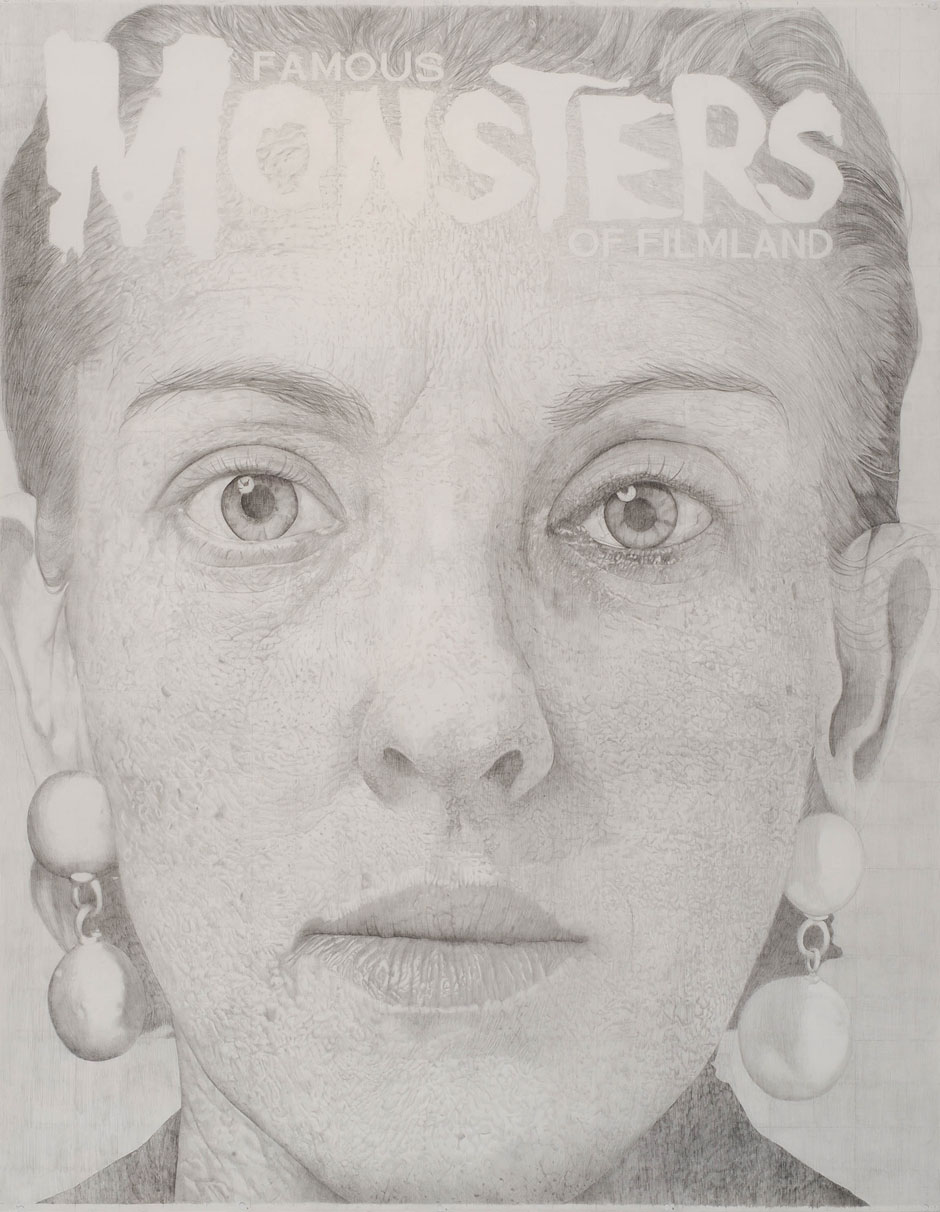

Shaw can be nerdishly Talmudic—a comic strip account of Genesis with Dick Van Dyke and Mary Tyler Moore as Adam and Eve, drawn in the style of Mad magazine artist Mort Drucker—and, as demonstrated by a photorealist portrait posing as a cover from the fan magazine Famous Monsters of Filmland he is an excellent draughtsman. Some of the juxtapositions in his works are relatively simple—an editorial cartoon H-bomb merged with a vacuum cleaner or a little movie that combines the abstract eye of the old CBS logo with some trippy raga pop.

Others are more complex: The Seven Deadly Sins, a large triptych from 2013, appropriates a dozen or more icons (John Steuart Curry’s mad prophet John Brown, Delacroix’s revolutionary Liberty, David’s martyred Marat, Ad Reinhardt’s art comics, Norman Rockwell’s Thanksgiving dinner, the student screaming in response to the Kent State massacre) floating like decorative splotches of graffiti against the backdrop of a colonial house complete with white picket fence. Almost like Teflon, the banal backdrop and the incongruously pastel palette repel and minimize the grim imagery and cloud the artist’s apparent critique—if it is a critique.

Shaw’s show may be titled “The End is Here” but he appears to share our national optimism. Although his obsessive faux naïve work dares you to find it creepy, it is more often strangely cheerful, as well as enigmatic. How nice to see a swarm of gnat-sized Superman clones in pink capes fly through a giant keyhole. How comforting the image of Blake’s Nebuchadnezzar, dressed in ill-fitting superhero garb and shackled to a golden nest egg, crawling across a suburban sky—perhaps the god of life insurance.

About twenty-five years ago, the Museum of Modern Art put up a much-maligned show on modernism and popular culture called “High and Low.” “The End is Here” could have been called “Low and Lower”—the dense squiggle of the small intestine is a favorite Shaw motif. Greil Marcus found “the old, weird America” in the eerie country songs, blues, and balladry collected in Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music; Shaw discovered his newer version in musty piles of second-hand magazines, televangelist sermonizing, and Salvation Army thrift stores. The inventiveness of the outsider effusions in Shaw’s collection of found paintings—the muscular Tinkerbell striking a pose in outer space, the Last Supper relocated to a fast food emporium, the still-life portraying a roll of purple toilet paper, the visualization of “night golfing” in Zimbabwe—stimulate Shaw’s own sophisticated and fanciful inside-out art.

The crazy thing is, as you work your way through this dense and mysterious show, the primitive self-expression that abounds in Shaw’s assemblage of amateur paintings and lunatic propaganda on the middle floor actually appears more tasteful and less challenging than the artist’s own work—almost as though these bizarre objects, examples of what Roger Cardinal called “an alternative mode of art,” were the academy against which Shaw established his own avant-garde.

Shaw may draw inspiration from the occult, the paranoid, the wacky, and the freakish, but his own work is unaccountably sunny, air-filled, uplifting and buoyant. His motto, taken from Keats, could be, “what the imagination seizes as beauty must be truth.”

“The End is Here” is on view at the New Museum through January 10, 2016.