In early 2017, Poland was supposed to unveil what is perhaps the most ambitious museum devoted to World War II in any country. A striking cantilevered tower of glass and red cement is now rising above the completed subterranean chamber that will hold the museum’s 37,000 objects. The largest of these—an American tank, a Soviet tank, and a German railway car—had to be installed with the help of cranes during construction. In its exhibitions, the Museum of the Second World War promised to tell the story of the 1930s and 1940s in an entirely new way. Unlike other museums devoted to history’s most devastating war, which tend to begin and end with national history, the Gdańsk museum has set out to show the perspectives of societies around the world, through a sprawling collection gathered over the last eight years, and through themes that bring seemingly disparate experiences together. It is hard to think of a more fitting place for such a museum than Poland, whose citizens experienced the worst of the war.

Yet the current Polish government, led by the conservative Law and Justice party, now seems determined to cancel the museum, on the grounds that it does not express “the Polish point of view.” It is hard to interpret this phrase, which in practice seems to mean the suppression of both Polish experience and the history of the war in general. The new government’s gambit has been to replace the nearly completed global museum with an obscure (and as yet entirely non-existent) local one, and then to claim that nothing has really changed. The substitute museum would chronicle the Battle of Westerplatte, where Polish forces resisted the German surprise attack on the Baltic coast for seven days in September 1939. Heroic though it was, substituting this campaign for the entirety of World War II means eliminating the record of how Poles fought for their country and their fellow citizens over the succeeding five-and-a-half years. Such a move also means throwing away a historic opportunity to redefine the world’s understanding of the war.

World War II remains the crucial conflict of the modern era, but until now no institution has attempted to present it as global public history. Unlike most comparable museums, the Gdańsk museum does not accept a conventional national history of the war, or follow a patriotic chronology of battle that is convenient for the elaboration of this or that official national memory. It commences well before the German-Soviet attack on Poland in 1939 and even before the Japanese attack on Manchuria in 1931—events that are usually taken as the starting points of the Europe and Asian conflicts, respectively. Instead, the museum begins with the crisis of world order after World War I: militarism in Japan, Stalinism in the Soviet Union, authoritarianism in Europe (including in Poland itself), fascism in Italy, and National Socialism in Germany. It devotes serious attention to the diplomatic crises of the late 1930s: the struggle for China, the Anschluss of Austria, the partition of Czechoslovakia, the Spanish Civil War, and the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact—the 1939 alliance between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union that gave Hitler the green light to attack Poland.

As István Deák has stressed in his recent study of the war, Europe on Trial, appeasing Hitler before the war led to collaborating with Hitler during the war; Stalin’s choice to placate Hitler in 1939, he notes, was not exceptional but emblematic. In its impressively sober approach to the issue of collaboration, the Gdansk museum presents wartime societies as groups of individuals who had to make decisions, even when the range of possible choices was limited to bad ones. Some degree of accommodation is an almost universal experience of war, the more so when the occupation is unusual, as these were, in the depth of the occupiers’ political and economic ambitions. That the same populations—including Poland’s—often collaborated with multiple regimes might challenge our intuitions about good and evil and the importance of ideology. But it is also an everyday truth about war that emerges from an approach that takes account of all the different aggressors and occupations.

Treating the bombing of civilians as a global theme, as the museum does, can unsettle stories of the war that are limited to one national perspective. Germans generally associate the bombing of civilians with the end of the war, with the devastation of German cities like Hamburg and Dresden by British and American air raids. Some Germans use these bombings as a kind of counter-balance to German atrocities in the war. Yet a global history of bombing civilians demonstrates that Italians were doing the same in Ethiopia much earlier, following standard European imperial practice. It was Germany itself that brought the imperial practice of mass bombing of civilians to Europe, during the Spanish civil war and then, massively, during the invasion of Poland. As German forces entered Poland in September 1939, the Luftwaffe experimentally bombed defenseless towns, and killed about 25,000 people in Warsaw alone. The American photographer Julien Bryan, who was in Poland at the time, caught on film German planes strafing fleeing civilians, or simply civilians who were at work in the fields. His camera is in the museum’s collection. But if bombing European cities was a German innovation, Americans will hardly be exonerated in this exhibit, which concludes with Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Advertisement

How the different powers treated prisoners of war is another theme of the planned museum that brings out crucial insights about the conflict. Here the museum gives special attention to a major German war crime that is almost entirely forgotten. After Hitler betrayed Stalin and invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, German forces deliberately starved three million Soviet prisoners of war. Here and throughout the museum, it is the curators’ insistence on a global and comparative setting that allows a shocking crime to take on an apprehensible form. The German effort to annihilate millions of captured Soviet soldiers makes no sense without some understanding of Nazi racism and Nazi obsessions with food security, which are the subjects of neighboring exhibits. Similarly, the museum will examine the starvation siege of Leningrad, in which another million Soviet citizens perished. One of the texts featured in this section is the heartbreaking diary of a Russian girl, Tanya Savicheva, whose family perished around her: “Only Tanya is left.”

The idea of a radical restructuring of society through war was common across Europe and Asia in the 1930s and 1940s. The planned museum will highlight the different approaches to occupation of the Soviets (before 1941, when the USSR becomes prey rather than predator), the Japanese, and the Germans, while showing that all three sought to rapidly transform the lands they conquered on a very large scale. Once again, German war crimes emerge more clearly in this comparative setting. The German intention to starve tens of millions of east Europeans, known to historians as the Hunger Plan, and German colonial settlement schemes of the early 1940s, known as Generalplan Ost, take on new meaning when juxtaposed with Soviet transformations of the very same territories in the 1930s (which brought famine to Soviet Ukraine and mass shooting actions in 1937 and 1938) and Japan’s efforts to pursue its own vision of economic autarchy and political domination over a large swath of Asian territory.

The Holocaust of European Jews is a theme of its own. The Gdańsk museum’s presentation of this singular atrocity is informed by these prior themes and by the most recent scholarship. The killing begins with the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, and continues as a series of shooting campaigns throughout the war. The technique of gassing by carbon dioxide is used to murder most of Poland’s Jews in 1942. The vast majority of the victims of the Holocaust are Polish and Soviet Jews; practically everyone who dies in the Holocaust either called Poland or the Soviet Union home before the war or was sent to German-occupied Poland or German-occupied lands of the USSR to be murdered. Because the Holocaust involved a number of stages that related to the progress of a complex war, and touched victims throughout Europe, an international museum of the war may be able to show its course more clearly than museums devoted to the crime itself.

Perhaps for Poland’s current leadership, this is the problem. For a full understanding of the Holocaust makes it very difficult to divide European nations simply into perpetrators and victims. The idea of Polish national innocence, which the current government seeks to enshrine, is far from innocent itself. If Poles were merely victims of Nazi aggression, then how do we account for episodes in the war in which Poles themselves were collaborators or perpetrators? What do we do, for example, with the keys of the murdered Jews of Jedwabne? In July 1941, when they were forced to gather in a public square by their Polish neighbors, the Jews of Jedwabne brought their keys. They assumed, of course, that they would soon be going home. Instead they were marched to a barn and burned to death. Their keys remained, and have been gathered by the museum. If the museum is cancelled, they may never be seen.

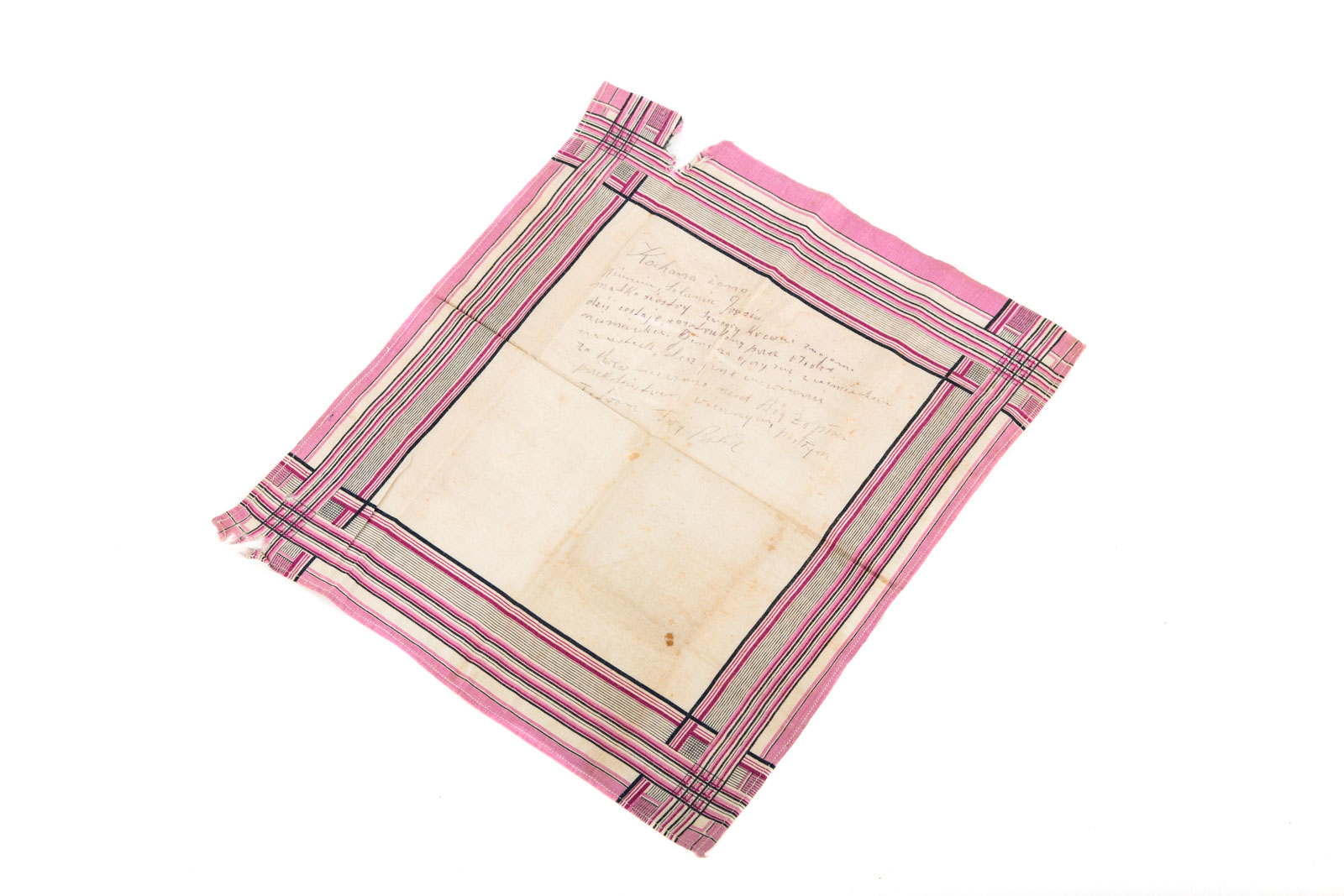

At the same time, the cancellation threatens the many artifacts that document the suffering of Polish families themselves by German or Soviet oppression. Consider the Wnuk family, where one brother was executed by the Germans and another by the Soviets, both in 1940. Bolesław Wnuk managed to leave a note for his family hours before his execution: “Today I will be shot by the German authorities. I die for the Fatherland with a smile on my lips, but I die innocent.” This text, written on his handkerchief, was passed by a Polish prison guard to the Wnuk family. Seventy years later the Wnuk family gave it to the Gdańsk museum. It is among the more than ten thousands objects donated to the museum for display and safekeeping. If the museum is prevented from opening, this artifact, like thousands of others, will be withheld from the public.

Advertisement

For all the government’s misgivings, there will be plenty of Polish heroism on display in the museum. Poland never surrendered to Germany, and the underground resistance known as the Home Army receives abundant attention. It was established in 1942 and fought its major campaign in 1944; redefining the museum to deal exclusively with the events of 1939 removes all this from view. Taken away as well would be the stunning contribution of Polish pilots to the defense of London from the Luftwaffe in 1940, and the work of Polish mathematicians to understand the German cryptography system known as Enigma. Very few people in the West know that two crucial elements of the British war story, the Battle of Britain and Bletchley Park, depended on Polish help. Without the Gdańsk museum, which has an Enigma machine to display, these Polish contributions are likely to remain in obscurity.

Telling a global history of the war is essential to showing the full extent of Poland’s plight and the Polish resistance. The First Polish Armored Division, for example, was formed in Britain, landed at Normandy, liberated villages and towns across France, Belgium, and the Netherlands, and fought its way across northern Germany. If Europeans knew that Poland had a victorious tank division, the stereotype of feckless Polish cavalry charging German armor might begin to recede. More dramatic still was the fate of the Polish Second Corps, patched together from men who were exiled to the Soviet east after the USSR invaded Poland in 1939. Allowed by Stalin to fight on the western front after Germany invaded the USSR, its men fought and died under British command in the battle for Italy in 1944. The charges on Monte Cassino, a moment of legendary physical courage were, for many of them, the last steps in what was already an inconceivable trail of tears. These soldiers’ story—Poland and defeat, Siberia and exile, the Middle East and marching, Italy and glory—is itself a global snapshot of the war.

Perhaps the greatest surprise in the Polish government’s decision is the implicit alliance with current Russian memory policy. The move to limit the Polish history of World War II to the week-long engagement with Germany at Westerplatte in 1939 follows a Russian script that is entirely on the record. In a speech at Westerplatte in 2009, Vladimir Putin accepted that Poland, and not the USSR, was the first victim of German aggression. But there was an important proviso, which he has amplified several times since. The German attack on Poland, Putin asserts, was a consequence of Poland’s own dealings with Nazi Germany before the war, rather than a result of the Soviet-German alliance of 1939 (which explicitly called for the division of Poland by the two powers) and the Soviet invasion that occurred in the same year.

The major Soviet oppressions of Polish citizens that resulted from the German-Soviet alliance and the Soviet invasion of Poland in September 1939 took place in occupied eastern Poland in 1940. Half a million Polish citizens were deported from Soviet-occupied eastern Poland to the Gulag in 1940. And the Gdańsk museum has collected the stars from the uniforms of some of the 22,000 Polish officers murdered by the NKVD in the Katyn massacre in April 1940, a humble reliquary of those Soviet death pits. Once the museum is out of the way, the Kremlin can be confident that no one else in Europe (beyond the Baltic states) will make the attempt to inscribe the Soviet aggression of 1939 and the occupation regime of 1939-1941 within the public history of the war.

A generation from now no one will care about the political feuds that animate Warsaw today. But it is certain that thousands of Polish families will remember that their precious gifts of family heirlooms were accepted and then refused. And when the cranes come a second time and remove the American tank, the Soviet tank, and the German railway car, dismantling the Polish and international history of the war, this too will leave a lasting impression, as well as some spectacular photographs. Most seriously of all, the effects of suppressing national memory could be of critical importance to Poles in coming decades, and to a global audience that has yet to fully absorb the complicated lessons of World War II. In some measure at least, how rising generations of Poles see themselves, democracy, and Europe will depend on whether they can have ready access to their country’s complicated experience in World War II. The collapse of democracy, the museum’s first theme, could hardly be more salient than it is right now. And the presentation of the conflict as a global tragedy could hardly be more instructive. The preemptive liquidation of the museum is nothing less than a violent blow to the world’s cultural heritage.