In 1929, the Surrealist poet Paul Éluard did away with the United States. In a map of the world attributed to him that year, the American republic (except for a giant Alaska) has been subsumed by Labrador in the north and a sprawling Mexico in the south.

The image of Mexico as the center of the new world—and as what André Breton called “the surrealist country par excellence”—is a take-away from the exhibition “Paint the Revolution: Mexican Modernism 1910-1950,” now showing at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Just as Éluard’s map can be read as an early polemic against Eurocentrism, so “Paint the Revolution” presents a Mexican response to European art that, at least up until World War II, was equal to and in some regards stronger than that of North America.

To a degree, “Paint the Revolution” is the story of the three star muralists, Diego Rivera, David Siqueiros, and José Clemente Orozco, who along with the posthumously canonized Frida Kahlo, defined the new Mexican art. (The exhibition borrows from the title, punctuated by exclamation point, of John Dos Passos’s 1927 New Masses article on the same subject.) But their work is situated among scores of lesser-known artists who were also responding to the decade-long Mexican revolution that broke out in 1910. Synthesizing avant-garde with folk art while embodying the tension between new and traditional media, these men and women engaged the central issues of early-twentieth-century culture.

Siqueiros’s Peasants (circa 1913), a pastel drawing of an idealized peon couple advancing into a cheerful hazy future, perhaps created before General Victoriano Huerta overthrew Mexico’s first revolutionary president Francisco Madero, suggests nothing more radical than domesticated Gauguin. The shock of the new is first felt with Francisco Goitia’s unsettling, James Ensor-like Zacatecas Landscape with Hanged Men I (circa 1914), a battlefield document painted while the artist served with Pancho Villa who, along with Emiliano Zapata and Venustiano Carranza, overthrew the Huerta dictatorship.

But a full-on avant-garde sensibility arrives only with Orozco’s vivid, sketchy paintings of scenes from a Mexico City brothel, The House of Tears (1910-1916), shown with several of his contemporary newspaper cartoons. Orozco subsequently merged reportage with expressionism in the 1920s with the tempestuous monochromatic ink-wash scenes of the civil war that followed Huerta’s ouster.

The connection between Mexican modernists and mass-produced agit-prop (also reflected in the elevation, by Orozco and other artists, of the nineteenth-century woodcut artist José Guadalupe Posada to a mythic forerunner) seems crucial. It finds fullest expression in the great murals first produced on behalf of the government during the relative calm and revolutionary consolidation of the early 1920s. These are represented in “Paint the Revolution” by tantalizing, if unavoidably inadequate, digital projections. Rivera, who received an official post, painted Ballad of the Agrarian Revolution and Ballad of the Proletarian Revolution for adjacent courtyards in the new Ministry of Education building in Mexico City.

Included in the Philadelphia show, the two murals show transfigured workers, frequently in white, engaged in all manner of production labor as well as celebrations of land distribution, together with heroic scenes from the revolution, and the occasional capitalist orgy. A new form of narrative serial art, they are as exalted (and didactic) in their allegories as a fifteenth-century church altarpiece. Soon, Mexico would surpass the Stalinized Soviet Union as the cauldron of revolutionary art.

More lurid than classical, Orozco’s The Epic of American Civilization, painted in the early 1930s on the walls of the Dartmouth College library’s reserve room (and also digitally represented), describes centuries of despoliation and oppression of one culture by another, leading up to the revolutionary destruction of the old order. The effect is of a flaming comic book filled with grotesque caricature, as when a group of skeletal academics (identified by the artist as “The Gods of the Modern World”) deliver a still-born child from a writhing, gutted cadaver; it is as outrageous in its way as the “wild style” graffiti’d exterior of a New York City subway car circa 1980.

Throughout its heyday, Mexican modernism was the realm of crypto comics. The versatile sometime cartoonist José Chávez Morado’s painting Troubled Waters (1949) seems to look back on the heroic period of the great muralists, drawing on both murals and the Sunday funnies in using a skyscraper construction site and some free-floating advertising posters to impose multiple panels over an urban landscape. As a kind of footnote to the exhibition, the talented, hugely successful illustrator Miguel Covarrubias is represented by a celebrity-packed cartoon—a mock mural originally published as a two-page spread in Vogue magazine, celebrating the Museum of Modern Art’s 1940 exhibition “Twenty Centuries of Mexican Art.”

Advertisement

MoMA’s then-president was Nelson Rockefeller, the man who in 1934 had ordered the destruction of Rivera’s unfinished, blatantly anti-capitalist Rockefeller Center mural (complete with portrait of Lenin). Nevertheless, Rivera and the muralists inspired a fashionable mexicanidad. (Among other attractions, Orozco was on hand during the 1940 MoMA show to paint a mural before an audience of museum visitors, a precursor of Marina Abramović’s performance in “The Artist is Present.”) By presenting contemporary art in the context of pre-Columbian artifacts, “Twenty Centuries” also celebrated a second tendency, characterized in the superb “Paint the Revolution” catalog as “Indianizing Mexico.”

Mexican artists had no need to seek a primitive tradition in the South Seas or equatorial Africa. Rather, they were free—or even obliged—to partake in a living primitivism. No one handled this “indianized” material better than Rivera, as in his stately, perfectly balanced Dance in Tehuantepec, a large canvas from 1928, which shows a row of barefoot Indian women in deep pink skirts facing their impassive male partners under an arch of green bananas; or more stylishly than Alfredo Ramos Martínez who, having relocated to Southern California, made many of his symmetrical portraits of peons on repurposed pages of The Los Angeles Times.

“Paint the Revolution” is filled with work elaborating on indigenous crafts, notably by the painters Rufino Tamayo and María Izquierdo—an artist who would be championed by Antonin Artaud, an early Surrealist visitor to Mexico—and the wood carver Mardonio Magaña. Another group, including Chávez Morado and the magic realist Antonio Ruíz, focused on urban folk forms like carnivals, parades, and street performers.

Adolfo Best Maugard worked in a more international primitivist style; his flat, patterned, Orientalist canvases bring him close to a third tendency, namely that of a transplanted European avant-garde. Rivera assimilated Cubism during his years in Paris but swerved back to more classical forms of representation. Local variants on Italian Futurism included the proponents of Estridentismo (Stridentism) and an unnamed group, including Juan O’Gorman, who painted industrial landscapes.

Most prominent were the quasi surrealists. The best known is Frida Kahlo (who repudiated the label “surrealist”), introduced with her smoldering Self-Portrait in Velvet (1926) as the equal to any long-necked Weimar flapper and represented by a number of jewel-like, symbol-laden canvases. Others include the credible abstractionist Carlos Mérida and the protean Agustín Lazo Adalid, who made a number of pieces in the tradition of Max Ernst’s collage novel Une Semaine De Bonté. Rivera too knocked off some surrealist work, notably The Communicating Vessels (Homage to André Breton) of 1938, a linocut so trippy in its biomorphism it could have been featured thirty years later in Zap Comix.

Rivera was a great twentieth-century painter. Siqueiros—subject of a 1921 proto-surrealist self-portrait that effaces his eyes—was more force of nature. A political organizer, who served time in prison and fought for Spanish Republic, Siqueiros is represented in Philadelphia by an assortment of woodcuts and lithographs made for various militant pamphlets, including the Communist broadsheet El Machete. (The best title belongs to another El Machete artist, Xavier Guerrero: Bats and Mummies Intend to Impede the Development of Revolutionary Painting.)

During the mid-1930s, when Siqueiros administered an experimental painting workshop in New York (to a group of students that included Jackson Pollock), his canvases grew increasingly dark. Brooding near-abstractions, The End of the World and Collective Suicide, were painted in 1936—the same year Artaud visited Mexico. Siqueiros began experimenting with synthetic pyroxylin paint to produce some figure studies so unabashedly ugly they might have been painted on black velvet. The Birth of Fascism was begun in 1936 and finished after he returned from Spain.

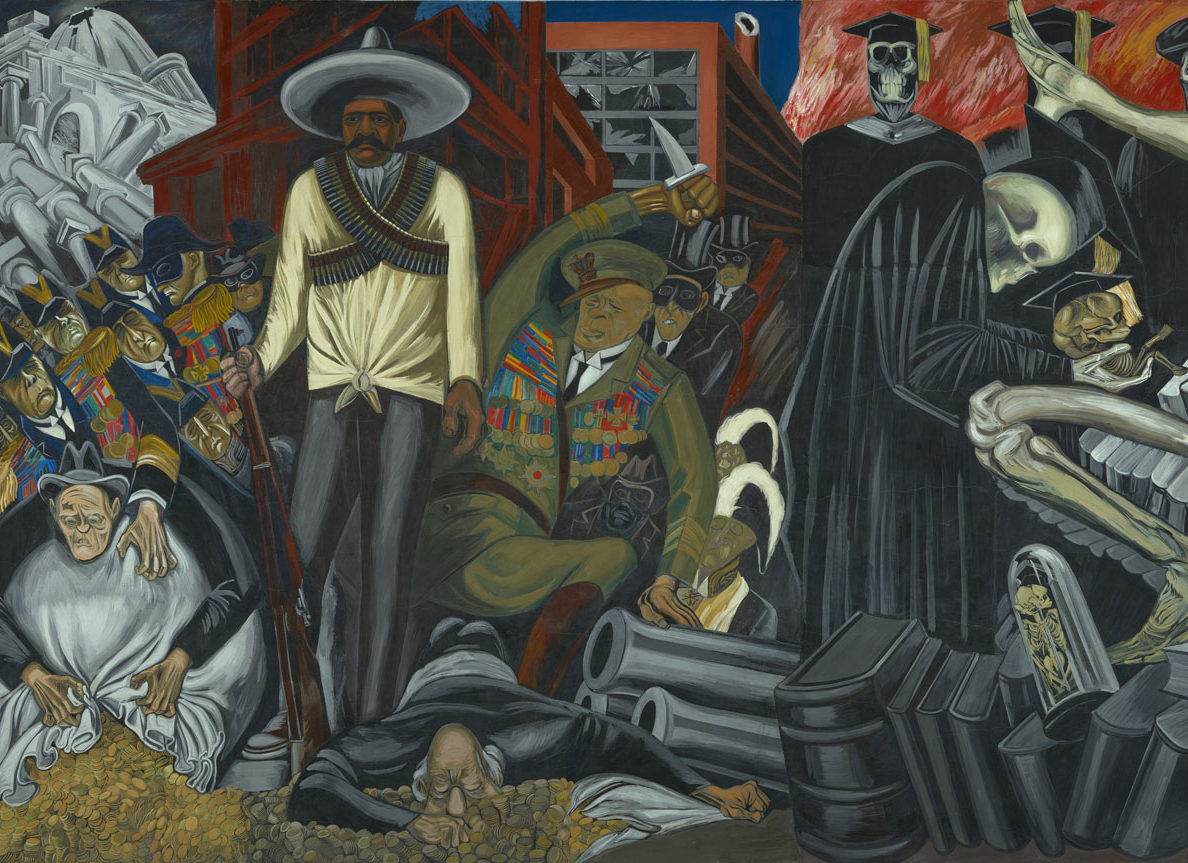

Shortly before World War II broke out, Siqueiros and his colleagues began work on Portrait of the Bourgeoisie, an astounding two-story painting in the stairwell of the Mexican Electrians’ Syndicate building. A majestic transmission tower looms over a visual cacophony of burning buildings, gas-masked plutocrats, revolutionary fighters, and a Moloch-like furnace converting the blood of the workers into coins: industrialism run amok! Garish, dizzying, and lysergic (even in digital projection), it seems a precursor of Jack Kirby’s muscular comic book art or even Jeff Koons’s monumentalized kitsch.

A few weeks after “Twenty Centuries of Mexican Art” opened at MoMA, Siqueiros staged a rival performance piece—storming Leon Trotsky’s villa in Mexico City’s Coyoacán suburb. He went into hiding, leaving the Spanish refugee and maker of photomontage Josep Renau to complete the mural.

“The consciousness of Mexico today is a chaos in which the new forces of an entire world are seething,” Artaud wrote in 1936. As Siqueiros’s vertiginous Portrait suggests, sometimes these social and political upheavals seemed to overpower the art. But in another sense they were the art.

“Paint the Revolution: Mexican Modernism, 1910-1950” is at the Philadelphia Museum of Art through January 8.