For Henry James’s seventieth birthday in 1913 a group of his admirers commissioned John Singer Sargent to paint him; and Sargent’s own birthday gift was to waive his fee. The novelist sat some ten times in the artist’s London studio, and the painter always asked him to bring some friends along—“animated, sympathetic, beautiful, talkative friends,” as James put it, whose conversation would break the “gloom in my countenance by their prattle.” That was Sargent’s usual practice, and the evidence of its success sits this summer at the entrance to “Henry James and American Painting,” a compact but wonderfully heterogeneous show at the Morgan Library.

The portrait presents James full-faced and with his baldness fringed by gray. His head tilts just a bit to the right, his eyes are slightly hooded, and his expression looks shrewdly confident and skeptical; judging us far more than we would dare judge him. He’s wearing his usual winged collar and a bowtie, and seeing it here—its regular home is London’s National Portrait Gallery—I was struck by the fullness of his lips and the warm tones with which Sargent has painted his face. In 1914 the painting went on display at the Royal Academy and was slashed with a hatchet by a suffragette, not because she had anything against either James or Sargent per se, but simply because it looked like a picture of masculine prominence. It was expertly patched and to my untrained eye the damage isn’t visible; but a picture taken at the time shows a gash at the temple and another across the mouth.

The Morgan’s exhibit includes a comprehensive selection of Jamesian portraits along with other paintings of and by his friends. His brother William had planned to become a painter before deciding in 1861 to take up science instead, and worked for almost two years in the Newport studio of William Morris Hunt. But in the end it was Henry who spent the most time in artists’ rooms, and got the most from it. He too had gone to Hunt, and put in his hours with charcoal and ink, though where William and his fellow pupil John La Farge drew from life, Henry merely copied plaster casts. Still, it was enough to give him a taste for the painter’s world, the portrait painter’s in particular. It was a sociable existence, its easy chat mixed with the purposeful work of the hands, and the solitary writer was drawn to it as he would later be to the drawing room or the dinner party. One consequence was the frequency with which he used the studio as a setting for his fiction, whether in the early Roderick Hudson (1875) or a tale from his maturity like “The Real Thing.” And another was that he himself was often painted or drawn or photographed.

He liked sitting, and the exhibition includes a round dozen of his many portraits; more probably than have ever been gathered in one place before. In one, a marvelous 1911 charcoal head by Cecilia Beaux, the novelist’s eyes are fierce, his baldness emphasized and egg-like. It’s matched by Abbott Handerson Thayer’s elaborately stippled 1881 crayon drawing, a three-quarters view that suggests the strength of James’s nose. And that nose figures as well in the earliest image of him here, a profile in oil that La Farge made in 1862. James was just nineteen, and his hair looks a burnt red; he seems pensive and unhappy—uncertain too—and the background has a touch of storm in it.

The show’s other La Farge was new to me, a half-length portrait of William James from 1859, a palette in one hand and the other extended beyond the frame, and with the canvas as a whole dominated by the white sleeves of his shirt. It’s again in profile, and taken together these images mark the two as brothers: the nose and the lips match, and so does the tilt of the head. But William is active not contemplative, he’s doing something; and looking at them together it seems that La Farge got at not only their similarity, but also the essential difference between them. Maybe that’s an overstatement—maybe I’m projecting what I know about that difference onto these pictures of teenagers. On a different day La Farge could well have done them differently, capturing William’s youthful irresolution and Henry’s sense of purpose of instead. Only he didn’t, and it’s a shame these two portraits normally hang separately, William at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, and Henry at the Century Association.

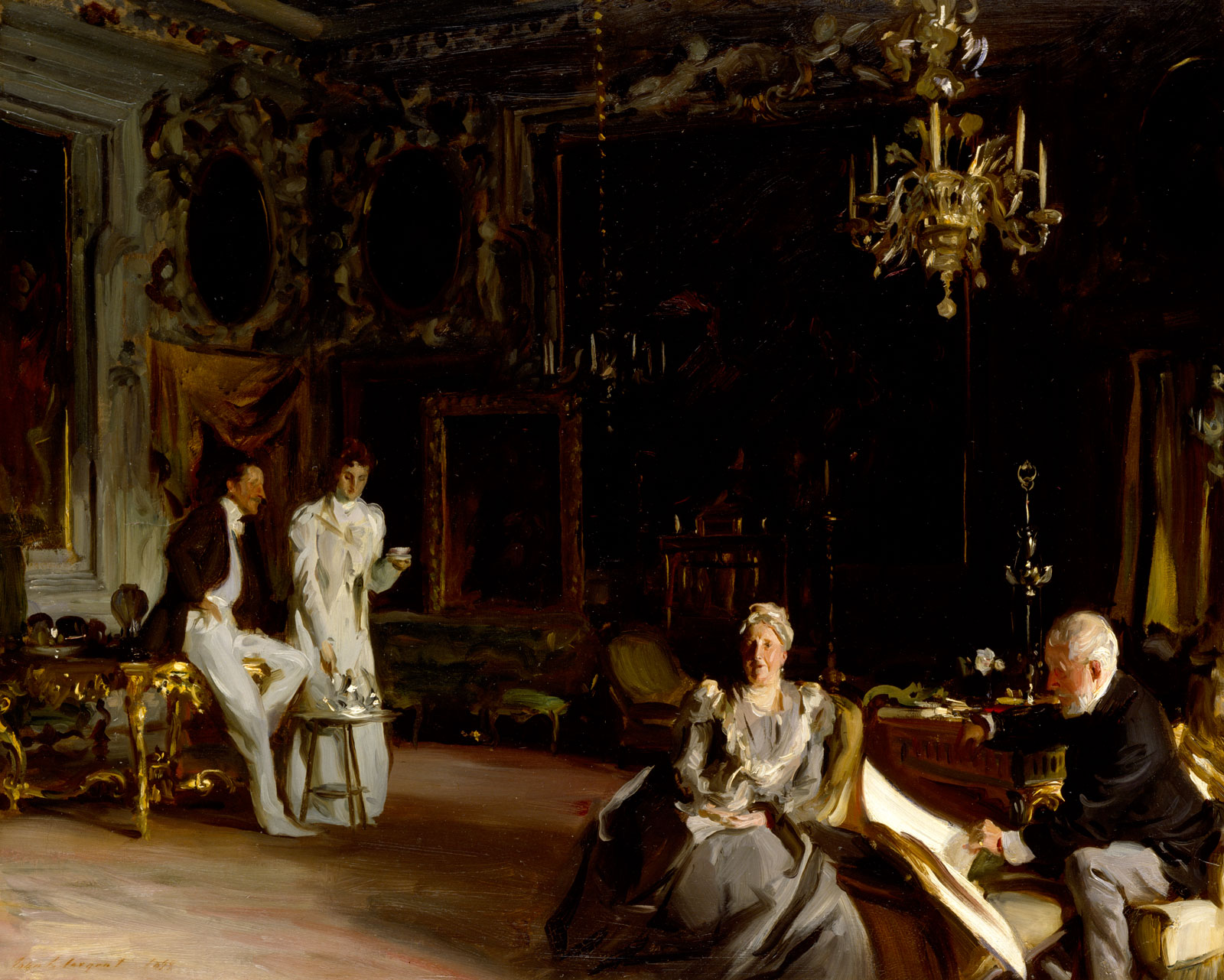

The exhibit’s pair of Whistlers is more familiar. So are its other Sargents, though there are some real treasures among them, including the Royal Academy’s 1899 An Interior in Venice, where the stiff luxury of its setting is undercut by the looseness of his brush. The freshest thing about this show is a set of paintings connected with some of James’s friends and experiences in Italy. The Villa Castellani sits at the top of a Florentine hill on the south side of the Arno, a structure with a “long, rather blank-looking” front that forms one side of a “little grassy, empty, rural piazza.” The words come from The Portrait of a Lady, and they describe the building in which the novel’s Gilbert Osmond keeps an apartment. The grass is gone now, but James’s account is otherwise exact to the place: an easy walk from the city’s center, for all that his characters complain about the climb, and with each turn of the road offering a new view, the olive-shrouded hills, the Duomo too large for human conception. The villa dates from the fifteenth century, and by James’s day was divided into flats “mainly occupied by foreigners of random race long resident in Florence.” One of them was a family friend named Francis Boott, a widower who lived on the proceeds of a Lowell textile mill along with his carefully-educated daughter, Elizabeth.

As individuals the Bootts had almost nothing in common with The Portrait’s Gilbert and Pansy Osmond. Nevertheless James drew on their situation—their closeness, their expatriation—in imagining his characters; and he also returned to them, as Colm Tóibín writes in the catalogue to this exhibit, in developing the Ververs of The Golden Bowl. Boott wrote music and Lizzie painted, and in 1879 she began to study with a good-natured but rough-mannered artist from Cincinnati named Frank Duveneck. James had already written admiringly of his work and he had a reputation as a skilled teacher; Lizzie fell in love with him, and over her father’s objections they married. Duveneck had just completed a full-length portrait of her when in 1888 she caught pneumonia and died. She stands against a gray wash of a background, all in brown—gloves and muff, dress and hat—and so impressively corseted that one can almost hear the whalebone creak. She had worn the same dress for their wedding, but her eyes here are steady and searching and sad; she’d just had a baby and her expression made me think, irresponsibly, about post-partum depression. The canvas is highly finished, indeed polished; but then so was Elizabeth Boott, and this painting’s honesty and pain seem unforgettable.

The show’s catalogue includes three highly suggestive essays by its co-curators. Tóibín’s is the most intensely biographical, slipping with practiced ease between James’s work and life, and tracing in that work the ghostly presence of the painters and sculptors he knew. Marc Simpson, formerly of Williamstown’s Clark Institute, writes exceptionally well about James as an art critic, noting both his puffery—he often reviewed his friends—and his blind spots. James wrote interestingly about the early Winslow Homer, admiring his skill while dismissing his subjects as “suggestive of a dish of rural doughnuts and pie.” But the list of American painters he ignored is a long one, Thomas Eakins among them. The Morgan’s own Declan Kiely details the library’s holdings of James’s manuscripts and letters, and the piece seems at first an outlier, though the exhibition does include several vitrines of his papers. But Kiely predicates the essay on James’s own ambivalence about such archival survivals, letters in particular; the result is sharp and alive and includes a glimpse of some still-unpublished correspondence with the expatriate American doctor William Baldwin. He was based in Florence, and his patients included everyone from Queen Victoria to Mark Twain, as well as James himself—who would have hated the idea of our looking over the doctor’s shoulder at the details of his health and diet.

James explored such invasions of privacy in stories like “The Aspern Papers” and “The Abasement of the Northmores,” and he tried to forestall posterity, knowing he would fail, by burning great piles of his own papers in 1909 and again in 1915. Among them, presumably, were the letters he’d gotten from Sargent, with whom in Simpson’s words he had an “apparently abundant correspondence.” They first met in 1884 and a few years later James encouraged the painter to settle in London, writing him up for the magazines and introducing him to other painters. They were guests at the same tables and depicted the same world; indeed some critics complained about their resemblance, as though they merely illustrated each other. The one surviving letter between them shows that they used first names—and yet James burned his files and Sargent simply didn’t save things. In writing to others the novelist rarely refers to Sargent the person as opposed to the painter, and we have never known, and never will, very much about their long friendship.

Advertisement

One portrait here that James mentioned as “very sure and charming” is that of a writer with whom both he and Sargent were friends—or a double portrait rather, an 1885 oil, Robert Louis Stevenson and His Wife. Fanny Stevenson lounges at one edge of the canvas, wrapped in a shawl—a few splashes of yellow and red—and with her feet bare. Meanwhile the writer paces, pulling at his mustache, his long body impossibly thin, and with the dimly Jamesian recess of a doorway swinging open between them. Sargent’s surface is rougher than in his society portraits, and some critics at the time thought it awkward. So it is, deliberately, and Stevenson loved it. He stands off-center, and looks out at us, looking too as if he’s about to leave the room, the frame. As the past, or other people, are apt to when you try to pin them down.

“Henry James and American Painting” is at The Morgan Library & Museum through September 10. The accompanying book by the same title is published by The Morgan Library & Museum with The Pennsylvania State University Press.