One of the most unforgettable exhibitions in my experience—“The Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age”—opened at the Museum of Modern Art fifty years ago, when I was a college junior. Organized by the Swedish curator Pontus Hultén, this provocative show ran a thrilling gamut of Western art, from an eighteenth-century Swiss automaton to Marcel Duchamp’s readymade Dada appropriations to a painted steel remnant of Homage to New York, Jean Tinguely’s self-constructing, self-destroying mechanized sculpture, which in 1960 blew itself up on cue in the MoMA sculpture garden.

As a product of my times, I’d already been well indoctrinated in the central Modernist principle that the mechanical is not only beautiful but preferable to the sentimental art of the past. MoMA has long played a central role in promulgating that concept, beginning with its 1934 exhibition “Machine Art,” curated by the twenty-seven-year-old Philip Johnson, who displayed boat and airplane propellers as if they were Brancusi sculptures and Pyrex laboratory glassware as if it were as precious as Baccarat crystal.

With that audacious presentation, Johnson, ever attuned to the Zeitgeist, defined the design equivalent of Precisionism, a hyper-realistic approach to painting endorsed that same year by MoMA when its principal founding benefactor, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, donated one of Charles Sheeler’s better Precisionist paintings, American Landscape (1930), to the museum’s permanent collection. That picture—which depicts with hallucinatory clarity what was then the world’s largest factory, the Ford Motor Company’s Rouge River plant in Michigan—is among 136 works chosen by San Francisco’s de Young Museum for its new exhibition, “Cult of the Machine: Precisionism and American Art.”

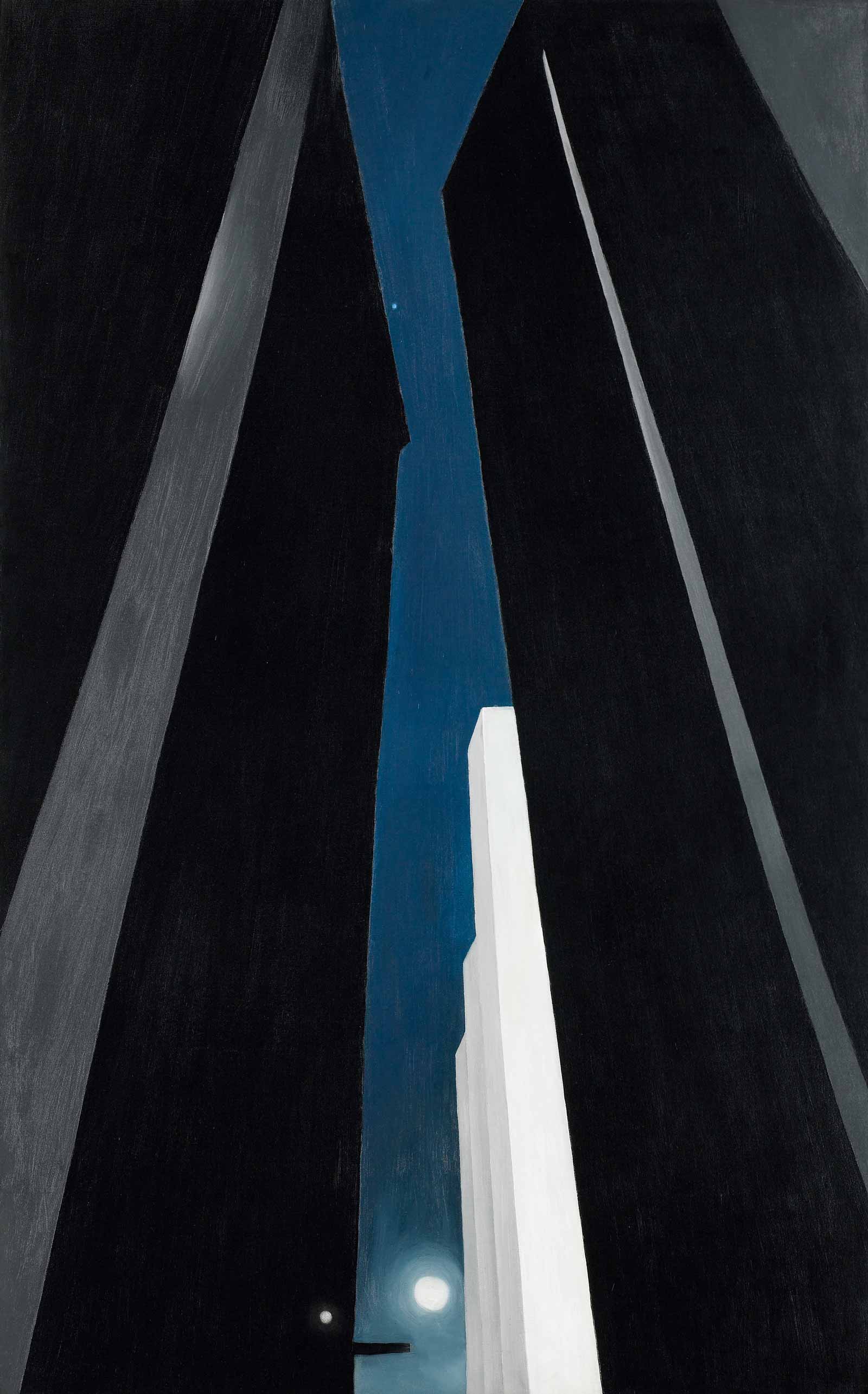

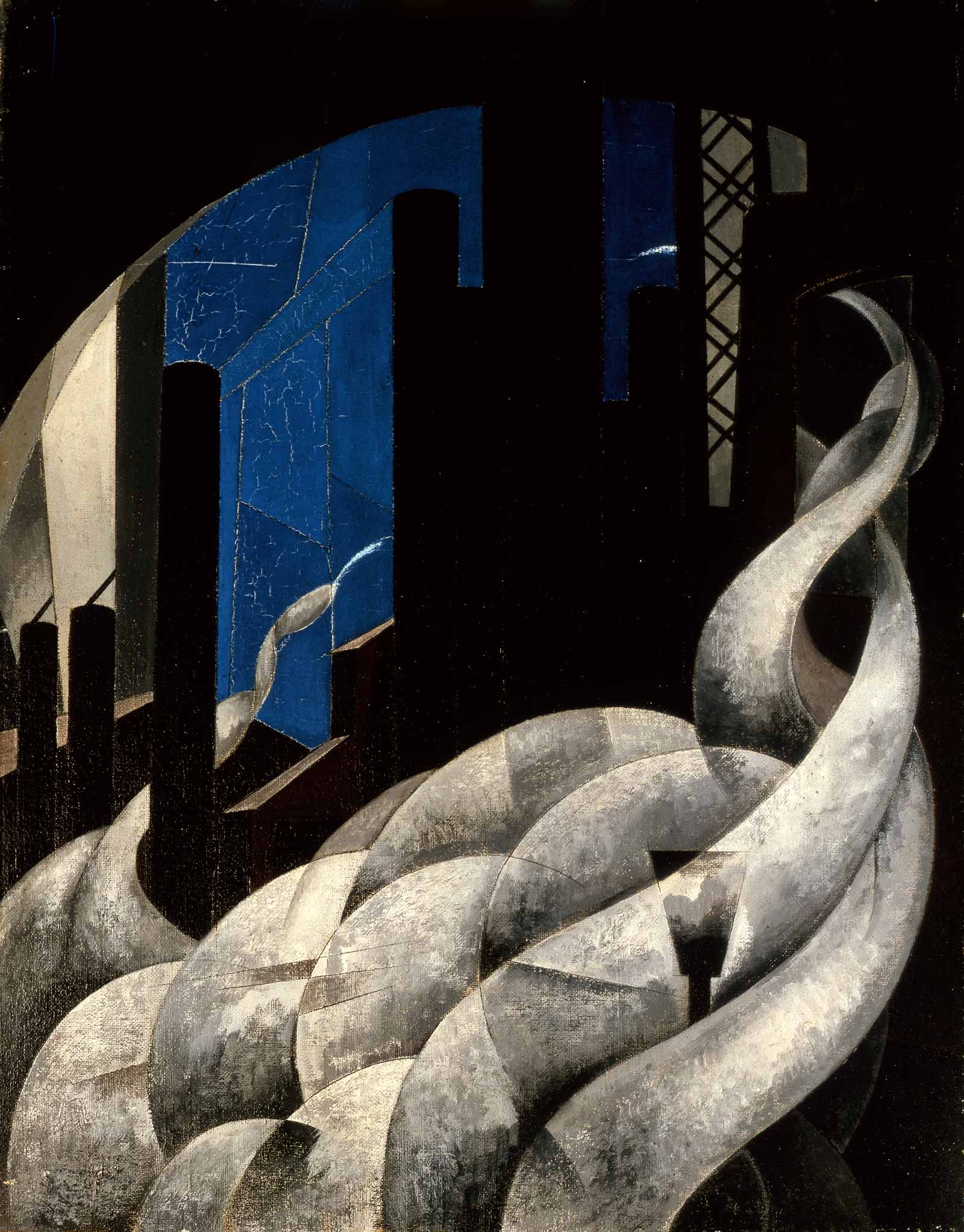

Tellingly, although this show includes twenty-three Sheelers (a veritable mini-retrospective in itself), Hultén had none at all in “The Machine.” Only five artists overlap the two exhibitions: the pervasive but always enigmatic Duchamp; Francis Picabia (the antic link between Dada and Surrealism); Morton Livingston Schamberg (tragically short-lived and vastly underappreciated); Joseph Stella (best-known for his totemic paintings of the Brooklyn Bridge); and Charlie Chaplin (represented by film stills from Modern Times, his 1936 critique of industrialization in which he is famously swallowed by gigantic cogwheels). On the other hand, “Cult of the Machine” goes out of its way to add women artists to this overwhelmingly male roster—not only celebrated names like Berenice Abbott, Margaret Bourke-White, and Georgia O’Keeffe, but also their lesser-known contemporaries, Victoria Ebbels Huston Huntley, Alma Lavenson, and Helen Torr.

The term Precisionism was first used in 1927 by Alfred H. Barr Jr., who would soon become MoMA’s first director, to describe a common tendency that emerged a decade earlier among a small, loosely affiliated group of like-minded American artists. They shared an affinity for industrial subject matter that inspired the critic Robert Coady in 1916 to write, in a riff worthy of the poet Carl Sandberg, that:

THERE is an American Art. Young, robust, energetic, naïve, immature, daring and big-spirited… The Cranes, the Plows, the Drills, the Motors, the Thrashers, the Derricks, the Steam Hammers, Stone Crushers, Steam Rollers, Grain Elevators, Trench Excavators, Blast Furnaces—This is American Art.… It is not an illustration to a theory, it is an expression of life—American life.

However, over the past decades, there have been frequent reiterations of this familiar subject matter, among them the Brooklyn Museum’s “The Machine Age in America: 1918–1941” (1986); “Precisionism in America, 1915–1941: Reordering Reality” (1994) at New Jersey’s Montclair Art Museum; SFMoMA’s “Native Modern: Charles Sheeler and Precisionism” (1999); the Met’s “American Modern, 1925–1940: Design for a New Age” (2000); and the Jersey City Museum’s “Industrial Strength: Precisionism and New Jersey” (2009). Thus the question inevitably arises, “Why again?”

The material on view in “Cult of the Machine” is, to be sure, perennially popular with the general public, which can easily discern simple visual congruities among diverse mediums that all partake in the same visual vocabulary—cocktail shakers that look like skyscrapers, skyscrapers that look like cocktail shakers, paintings that resemble photographs, cars reminiscent of zeppelins. But to a great extent, it all comes down to stylization, and even mere styling, the manipulation of form in the service of image rather than meaning.

Yet another recap of Precisionism is no coincidence when it occurs at the epicenter of America’s information technology industry. To the chagrin of old-guard San Francisco museum patrons, since the tech boom began in the 1990s, Silicon Valley tycoons have rarely donated to local art institutions in proportion to their stupendous wealth. In 2017, San Francisco ranked only sixteenth among American cities in its residents’ giving to non-profit organizations, but it was first in support for environmental causes. (Cincinnati residents were the most generous to cultural institutions last year.) Thus, even though the timeline of the current show ends many decades before the advent of the Digital Age, the exhibition publication tries to draw parallels between the simultaneously celebratory and anxious ethos that inspired Precisionism and present-day concerns about the impact of electronic technology on society. It is not far-fetched to see one more revival of this particular subject as a calculated effort to stimulate interest among philanthropically disengaged tech billionaires.

Advertisement

As the Stanford professor Adrian Daub argues in his catalog essay, the worship of technology in the early twentieth century has more than symbolic parallels with the way electronic media have transformed life in the early twenty-first. The other contributors emphasize that the rationalism implied by Precisionism’s highly controlled aesthetic was hugely appealing after World War I’s apocalyptic chaos, an American equivalent to the Retour à l’ordre (return to order) that emerged at the same time in European modernism. For example, Le Corbusier—who extolled airplanes, automobiles, and steamships as objects of sublime beauty equal to the works of the ancients—was producing Purist paintings analogous to Precisionist efforts.

One of the most noteworthy aspects of Precisionist painting is its almost complete absence of human figures (although workers occasionally appear in photographs of factories and construction sites). In reality, such urban scenes of high-density city centers and busy industrial sites would have been alive with pedestrians or laborers, yet the paintings of Sheeler, Ralston Crawford, Charles Demuth, and company are eerily depopulated. In an interview for the Walker Art Center’s 1960 exhibition “The Precisionist View in American Art,” its organizer, Martin Friedman, asked Sheeler about this anomaly. The artist blandly replied that such vacancy showed “what a beautiful world it would be if there were no people in it.”

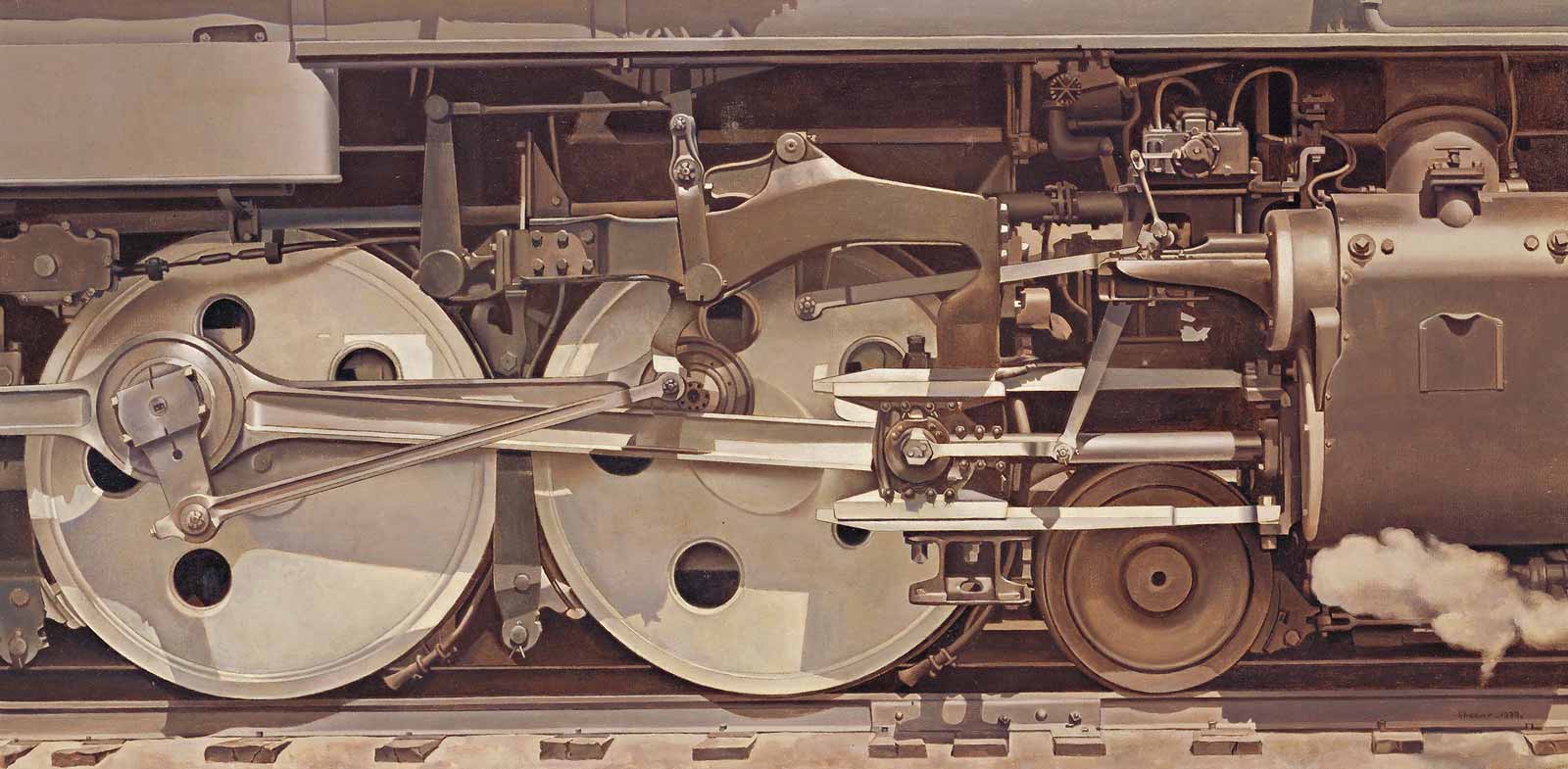

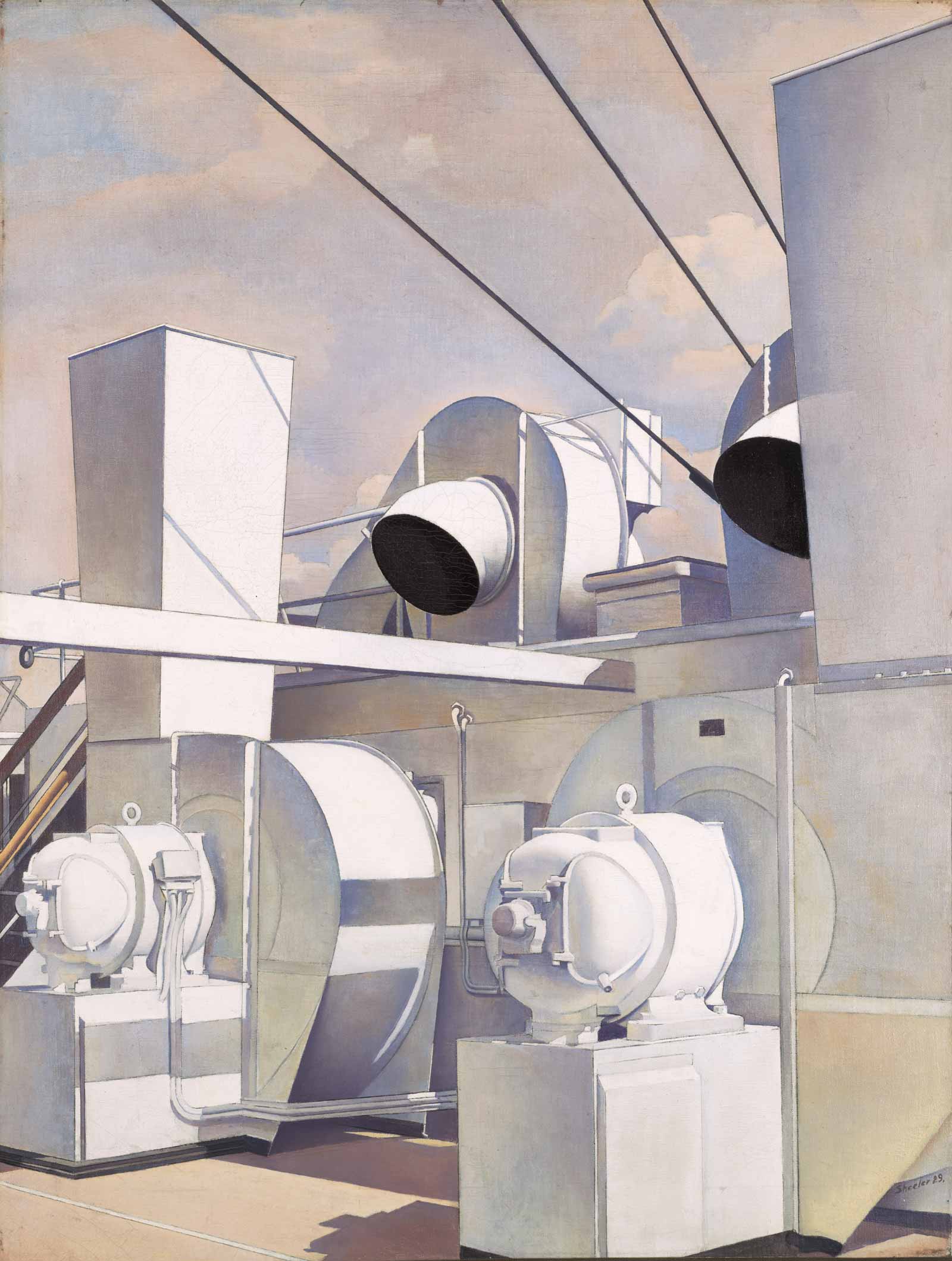

Two virtually identical Sheeler works in “Cult of the Machine” epitomize the hermetic nature of the Precisionist project. His photograph Upper Deck (circa 1928) served as the prototype for his oil-on-canvas Upper Deck (1929), both of which depict the same mechanical details of a steamship’s superstructure. They differ only in their monochromatic tonality (the photo silvery, the painting whitish) and size (the copy is three times larger than the eight-by-ten-inch original). Considering how many nineteenth-century photographers struggled to give their images the handcrafted look of paintings, Sheeler’s demonstration that he could do the exact opposite speaks directly to Precisionism’s technocentric view of the modern world, and prefigured the Photorealist painters of the 1960s. But whereas the Precisionists celebrated the man-made as an expression of humanity’s ability to create a perfect world, the Photorealists reacted against both Abstract Expressionism’s rejection of realism and Pop Art’s sendup of commercialism.

Quite different in spirit from the other paintings on view are my favorite works in the show, two playful oils by Gerald Murphy, a rich American expatriate who worked as an artist in France for just eight years during the 1920s and produced only about fourteen pictures. (He and his wife, Sara, are now best remembered as the prototypes for Dick and Nicole Diver in their friend Scott Fitzgerald’s Tender is the Night.)

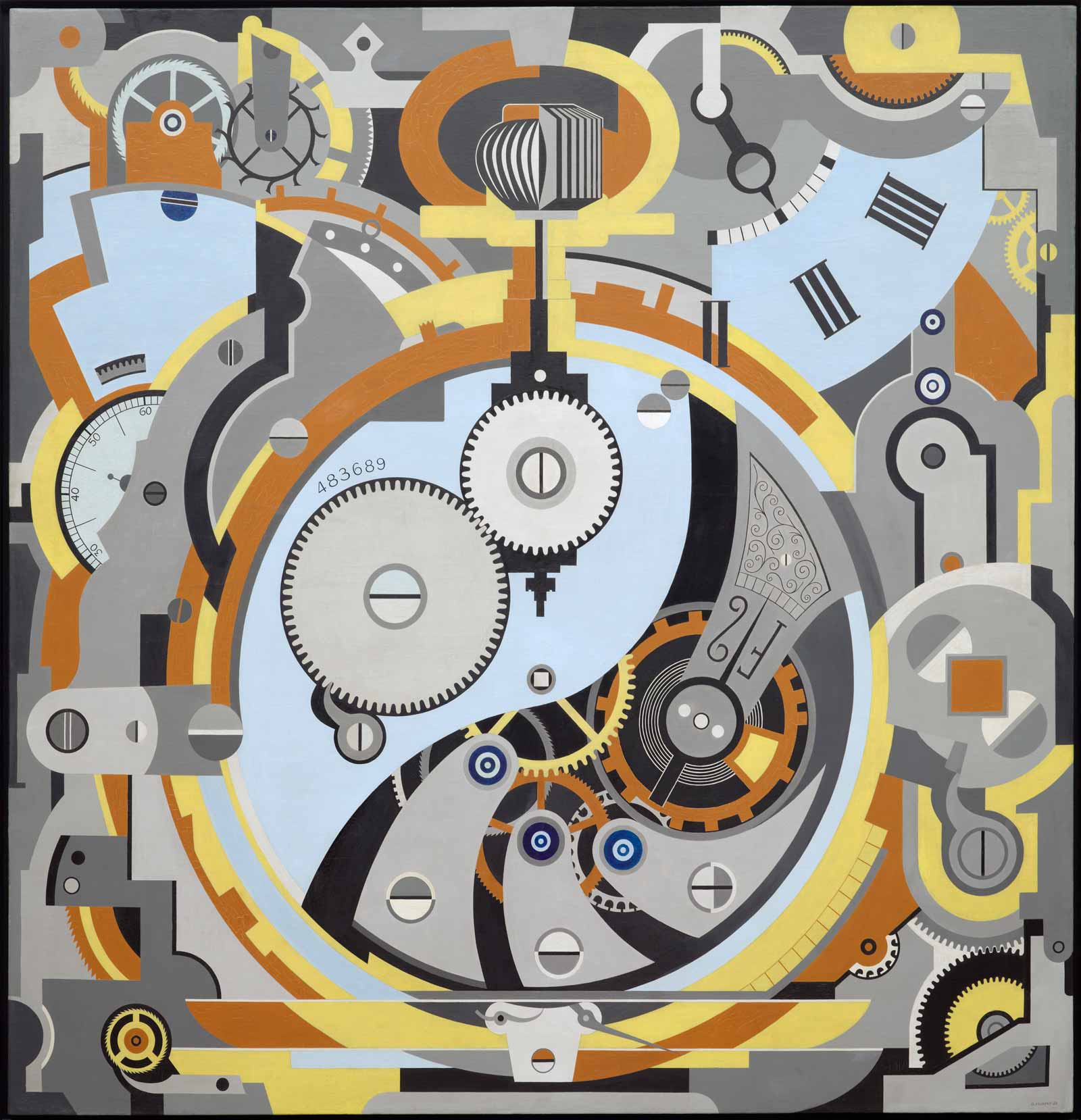

Murphy’s masterpiece is Watch (1925), a six-and-a half-foot-square canvas that depicts a super-scale timepiece that presages both Abstract Expressionism, in its oversized dimensions, and Pop Art, in its flattened, almost cartoon-like representation of an everyday object. The artist executed this whirling mandala with immaculate exactitude, and deconstructed the workings of the watch with intriguing minuteness of observation. Yet, despite its mechanistic references, Murphy’s painting conveys the enormous flair and sense of fun we associate with the Jazz Age, which are largely absent from this earnest, but ponderous, survey.

“Cult of the Machine: Precisionism and American Art” is at the de Young Museum in San Francisco through August 12, 2018, after which it will travel to the Dallas Museum of Art from September 9, 2018 through January 6, 2019. The Cult of the Machine: Precisionism in American Art, by Emma Acker with Sue Canterbury, Adrian Daub, and Lauren Palmor, is published by the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco/de Young in association with Yale University Press.