The twentieth century was not kind to the Romanovs. The night of July 16–17 marks the centenary of the murder of Tsar Nicholas II and his family by their Bolshevik guards at Yekaterinburg. As the revolution raged on, scores of members of the Romanov family perished in woods, mines, and prison yards; those who survived, labeled enemies of the people, were forced out of the country. This tragic conclusion of a 300-year-old dynasty was not, however, the end of the Romanov family. Despite the immense trauma they had suffered, the Romanovs endured, adjusting to their new circumstances. Throughout these trials, they had an unlikely ally: art.

Almost all the Romanovs had an artistic bent: they painted, doodled, carved, embroidered, cut jewelry, or sculpted. As Russia’s rulers before the 1917 revolution, their communications with the world were governed by official considerations; the personal remained invisible to the society at large. But there were flesh-and-blood men and women behind the scepter, tiaras, and ermine mantels, and they felt, processed, suffered, rejoiced, raved, prayed, and reminisced. To a family whose every move was watched and discussed, art offered an avenue to channel individual experience in a private mode.

For many Romanov exiles—hounded, stripped of their wealth, living under the constant fear of further reprisals—art became, in part, a coping mechanism. Later, as the memory of the massacre gave way in its immediacy, new generations of Romanovs took to art for reasons not so different from the rest of us: to meditate, to understand, and to express.

Over the twentieth century, the Romanovs produced a vast artistic trove that few are aware of, since most of their creative output was meant for family consumption. Because the family was scattered around the world by the events of the revolution, that collection is currently dispersed among private archives, family albums, basements, under-the-bed boxes and, in rarer cases, museums and galleries. When studied as a whole—in as much as its fragmented nature affords—two persistent themes emerge. One is the Romanovs’ intense, penetrating view of nature. For centuries, nature exploration has been a favorite Romanov family pastime. In those inimitable Russian forests, mountains, and steppe, they found aesthetic pleasure, refuge, and, at times, salvation.

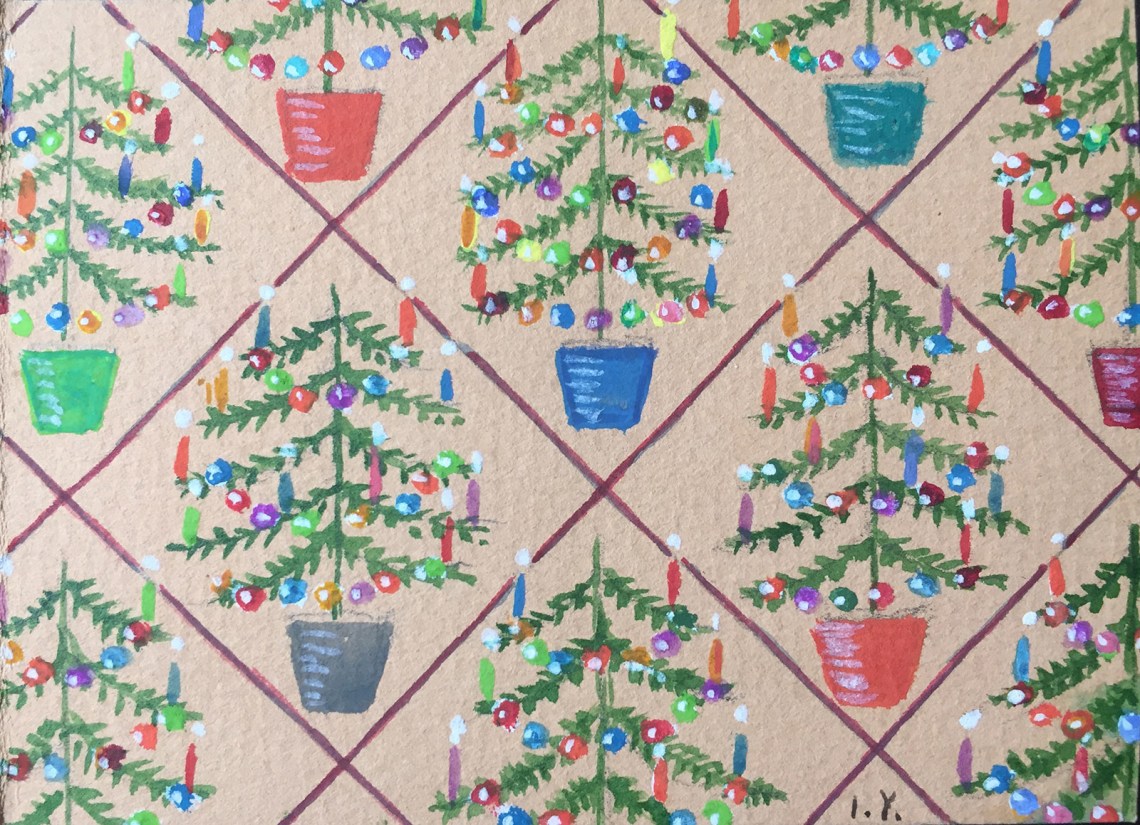

The second is the idiosyncratic playfulness with which the Romanovs used art as family entertainment. The colorful vignettes and illustrations that decorate their letters, the doodles and cartoons, the hand-drawn holiday cards and booklets, the tchotchkes and painted pebbles they gifted each other at birthdays and anniversaries amount to a secret language developed and reinvented from generation to generation in ways that even the scattered state of the family in the twentieth century could not undo. Imaginative, often humorous, and at times fantastical, these artifacts paint a different, more authentic portrait of a family whose life and legacy continue to pique our interest, one hundred years after the Romanovs were swept off the world’s political stage. For what is art if not a window into another’s mind?

Dagmar

For Empress Maria Feodorovna, wife of Alexander III and mother of the last tsar, Nicholas II, painting was a lifelong pursuit. Born as the Danish princess Dagmar, she studied art with her mother, Queen Louise, and was proficient at painting in both watercolors and oils. She ensured that all her children painted, too. The serenity of her son Nicholas’s early watercolors makes for an eerie contrast with the violence that would soon engulf the future tsar’s land and his family. Nicholas’s daughters, Olga, Tatiana, Maria, and Anastasia, and his son Alexei also painted; the cards they sent to other family members were often hand-drawn.

Maria Feodorovna was destined to outlive her husband and witness the destruction of his dynasty, as well as the disappearance of her two younger sons, five grandchildren, daughter-in-law, and numerous close relatives. In 1919, King George V, her nephew, sent the battleship HMS Marlborough to evacuate her and her immediate family from Crimea. “I think about you a lot and remember the good times past, when we were all living together,” she wrote on black-bordered mourning notepaper to her grandson Nikita Alexandrovich, who was by then living in a “grace and favor” house in England, from her native Denmark, where she spent the rest of her life. Her funeral, in 1928, was the last time a large group of Romanovs collected for more than half a century.

Xenia

Maria Feodorovna’s older daughter, Xenia, another HMS Marlborough passenger, was known for her miniatures. A pleasure pursuit during happier days, in exile Xenia’s art was frequently sold to benefit Russian refugee causes or gifted to family. She had survived an eighteen-month-long imprisonment at the family’s Crimean estate along with her mother, Dagmar, her sister Olga, her husband Sandro, and six of her children. “To watch and realize that our country is being destroyed, and so senselessly, is unbearable,” Xenia wrote to her brother Nicholas in Siberia in November 1917. In exile, Xenia spent most of her time on charitable causes and in supporting her large family. Estranged from Sandro, she lived on a small allowance allocated to her by the Windsors and on the proceeds from the sales of her jewelry. She wasn’t the only seller: in the 1920s, the Soviet government auctioned off confiscated Romanov treasure in London, including items that belonged to Xenia personally. Among the few things Xenia bequeathed to her grandchildren were two albums with drawings of her former jewelry collection that she had sketched together with her father, Alexander III, at the turn of the century.

Nikita

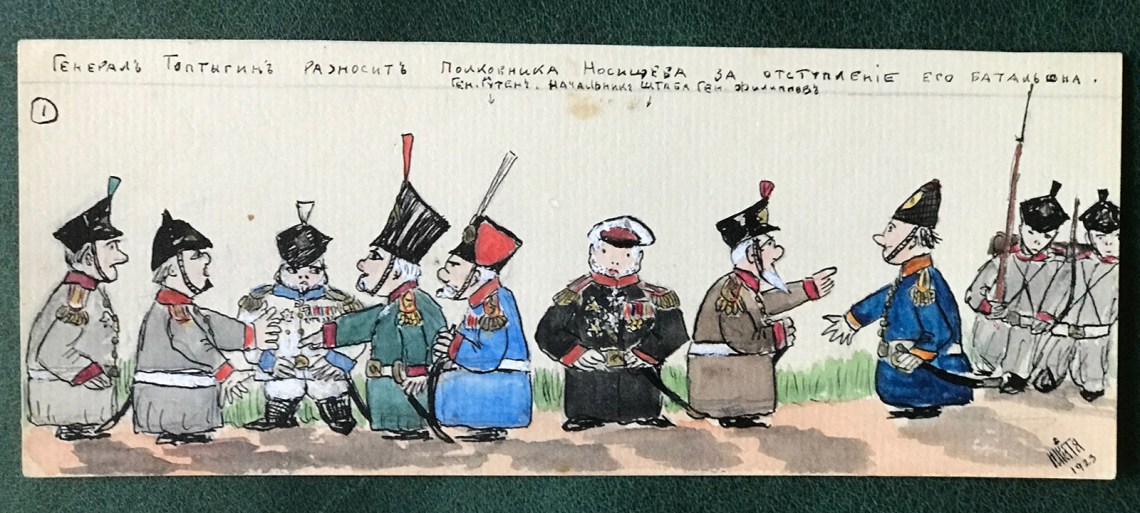

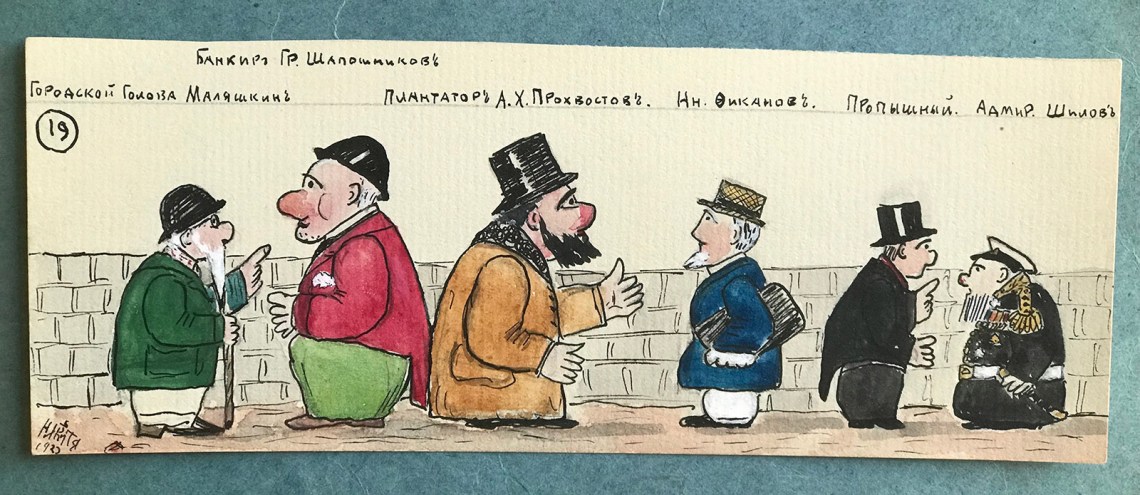

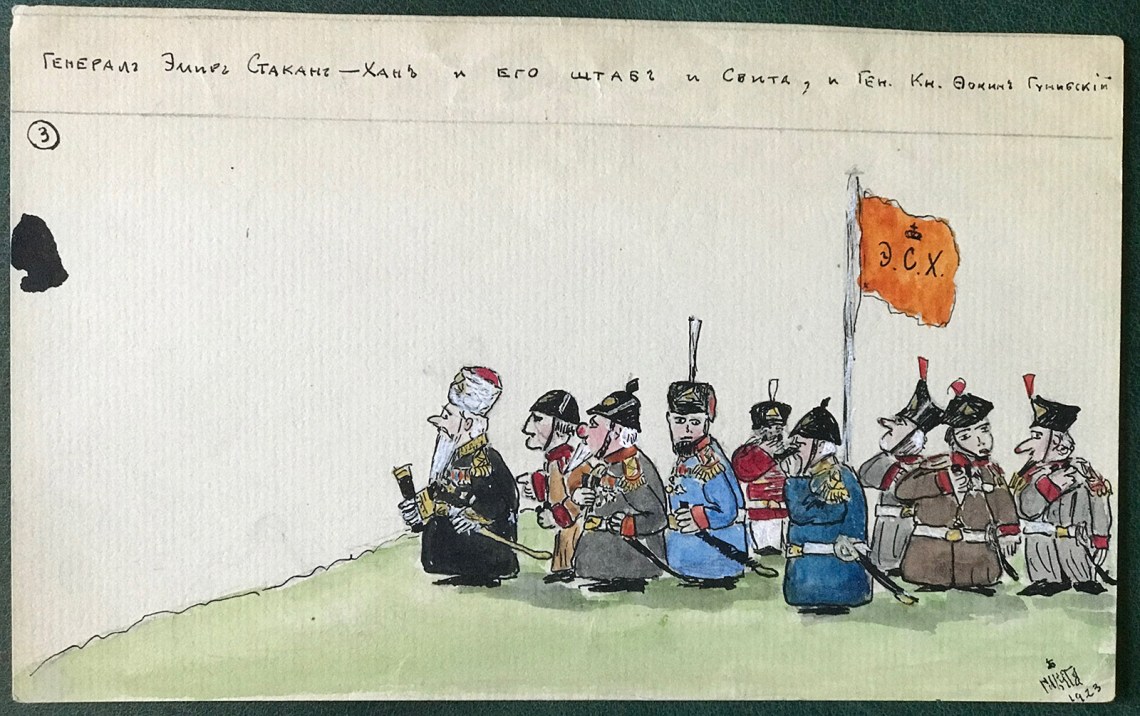

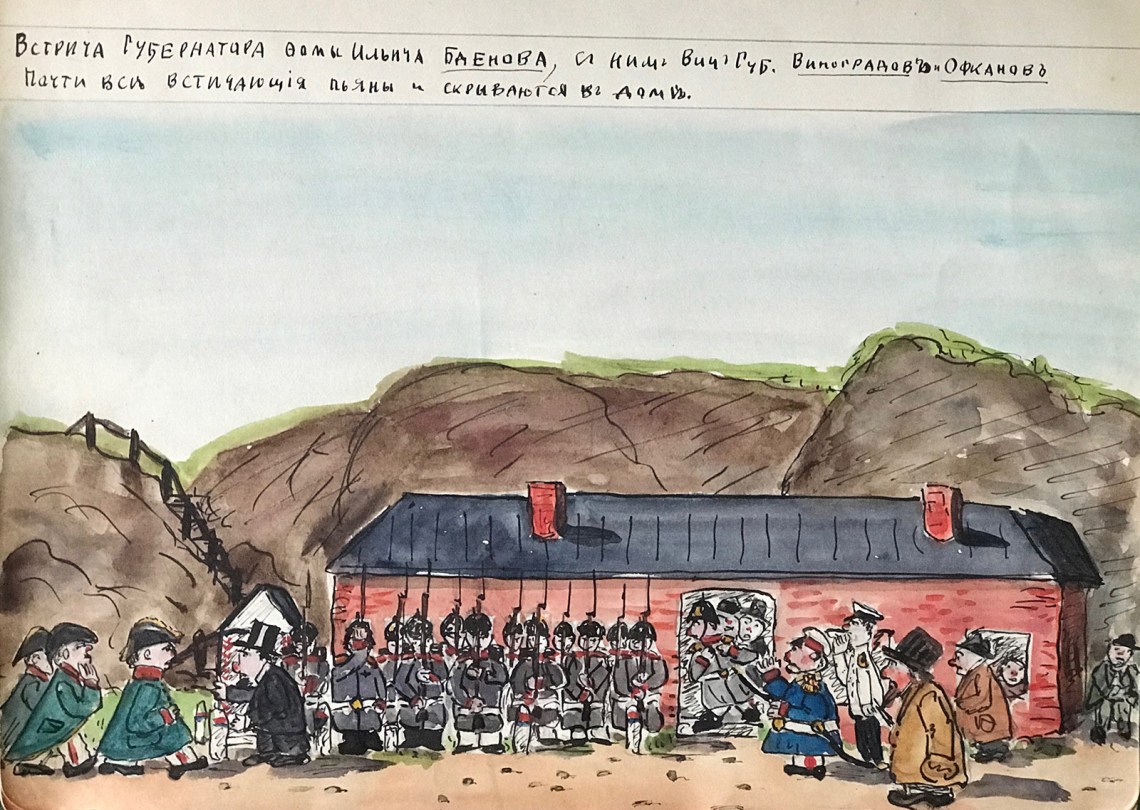

Also aboard HMS Marlborough was Xenia’s nineteen-year-old son, Nikita Alexandrovich. Nikita carried with him a box of cartoons he’d started drawing a few years before the revolution. Designed to work as animation-style sequences, with humorous captions in imperial Russian, Nikita’s colorful vignettes followed the adventures of the imaginary Prince Sharikov as he entertained friends at his estate in the Tula region, received peasant delegations, and vacationed in France. In exile, as Nikita changed countries and occupations, Prince Sharikov was promoted to political office as prime minister, appointing his cabinet, strategizing over battle maps, and scolding sloppy generals. Hundreds of these watercolors ended up in the United States, where Nikita, by then a married man and a father, tried his hand at merchant banking and teaching Russian in a military academy. He lived to be seventy-four, and died in Cannes, France, in 1974, never having assumed any citizenship. Like most exiled Romanovs, Nikita considered himself a citizen of Russia.

Olga

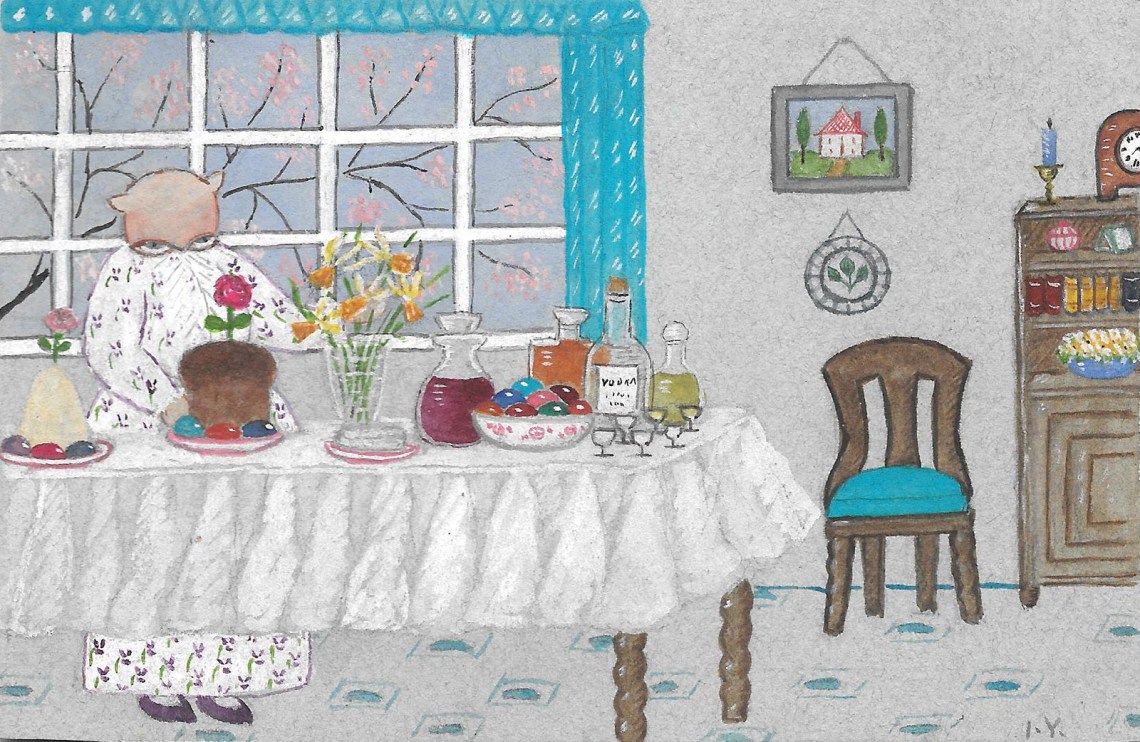

Nikita’s aunt Olga, younger sister of Xenia and Nicholas II, became the most prolific artist of the Romanov family, with a museum to her name and hundreds of paintings sold worldwide. Among her fondest childhood memories Olga counted looking through her father Alexander III’s teenage drawings of a fantasy city populated by pugs. Olga studied with some well-known artists of her time and served as a patron to art societies. After an unhappy first marriage, on the eve of the revolution she married her long-time love, Captain Nicolai Kulikovsky. Together, they lived through the Romanovs’ Crimean imprisonment and a year of hiding in southern Russia. In 1920, as the fortunes of the anti-Bolshevik White Army deteriorated, the Kulikovskys finally fled Russia via the Black Sea, with their two young sons.

In exile—first in Denmark, then in Canada, where the family moved after World War II—Olga’s bright still-lifes and genre scenes gained a steady following. She gave most of them away at Russian bazaars and as gifts to family and friends, but she also sold many, the proceeds serving as supplemental income to the farm that provided for the family. In her art, Russia appears unspoiled by war and revolution, permeated by the light her memory imparted to the land she loved. Born in a 600-room palace at Gatchina, near St. Petersburg, Olga shunned formalities and pretensions, believing that her best dress was the one she put on before standing before her easel. She died at the age of seventy-eight in 1960, outliving her husband by two years.

Maria

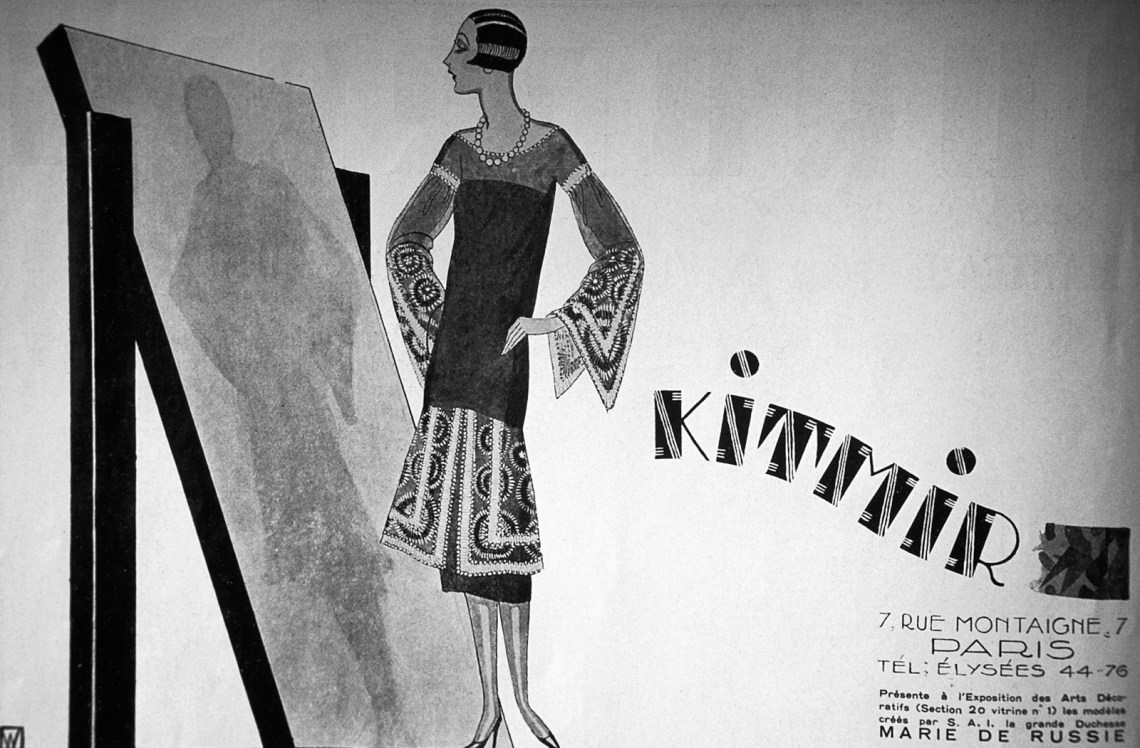

Another Romanov woman whose artistry saw her though tough times was Maria Pavlovna, daughter of Tsar Nicholas’s uncle Pavel, who was murdered in 1919. Maria escaped Russia by presenting to the German patrol a document that identified her as a former Swedish princess, which she had hidden in a piece of soap. In strained circumstances in exile—first in London, then in Paris—she began sewing her own clothes. Her fashion sense and embroidery talents caught the attention of Gabrielle (Coco) Chanel, who made Maria her exclusive embroidery supplier. (Chanel also enjoyed an affair with Maria’s brother, Dmitry, who had been involved in the conspiracy to murder Rasputin; their relationship furthered Chanel’s fascination with Russian themes.) Although the embroidery house Kitmir that Maria founded existed for only a few years, it gave work to scores of Russian refugee women—and pulled its owner out of “sleepwalking,” as Maria described her state after the revolution. She published two volumes of memoir, lived and worked in the US and Argentina, and died in Germany in 1958, at the age of sixty-eight.

Advertisement

Irina

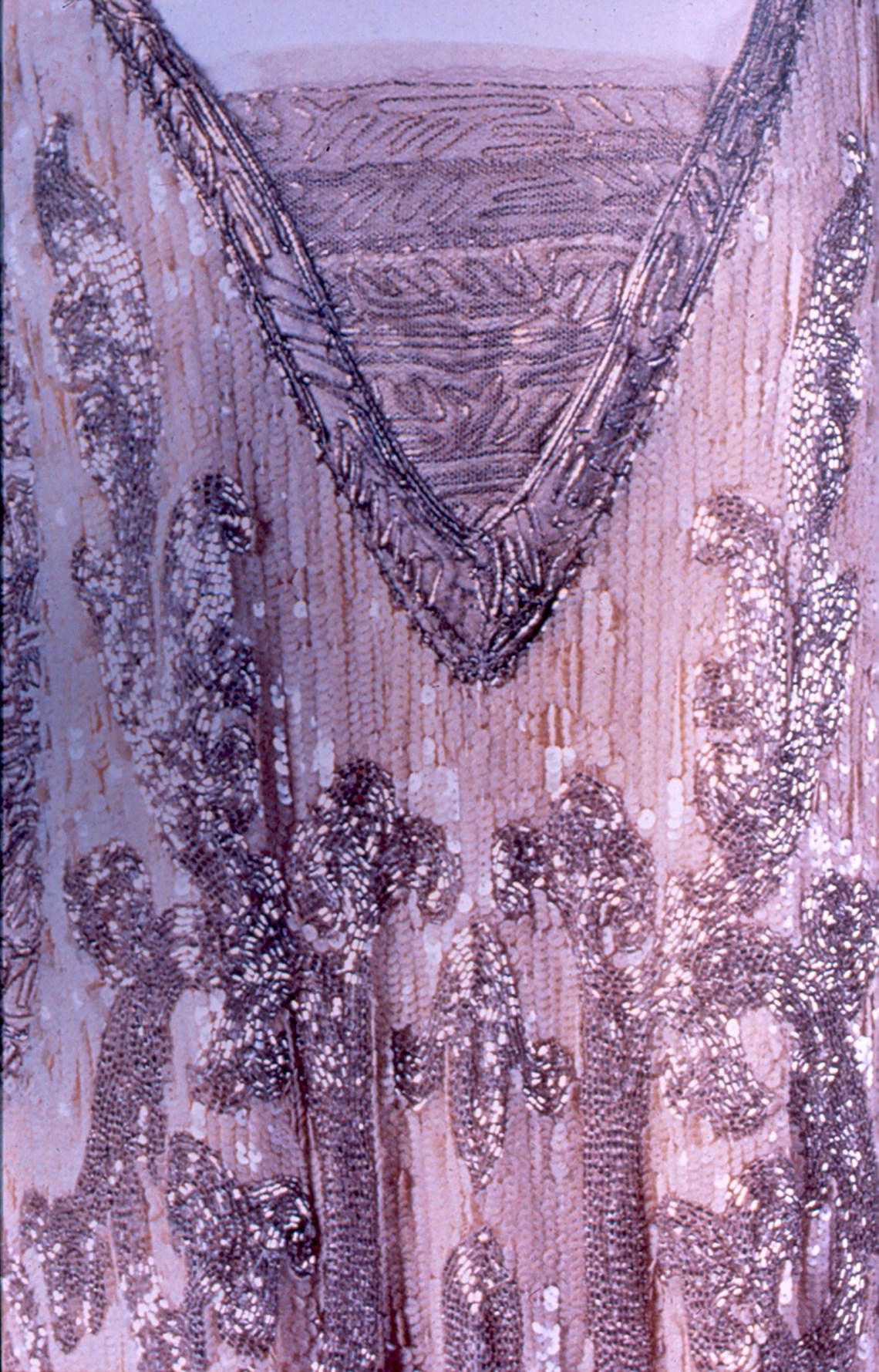

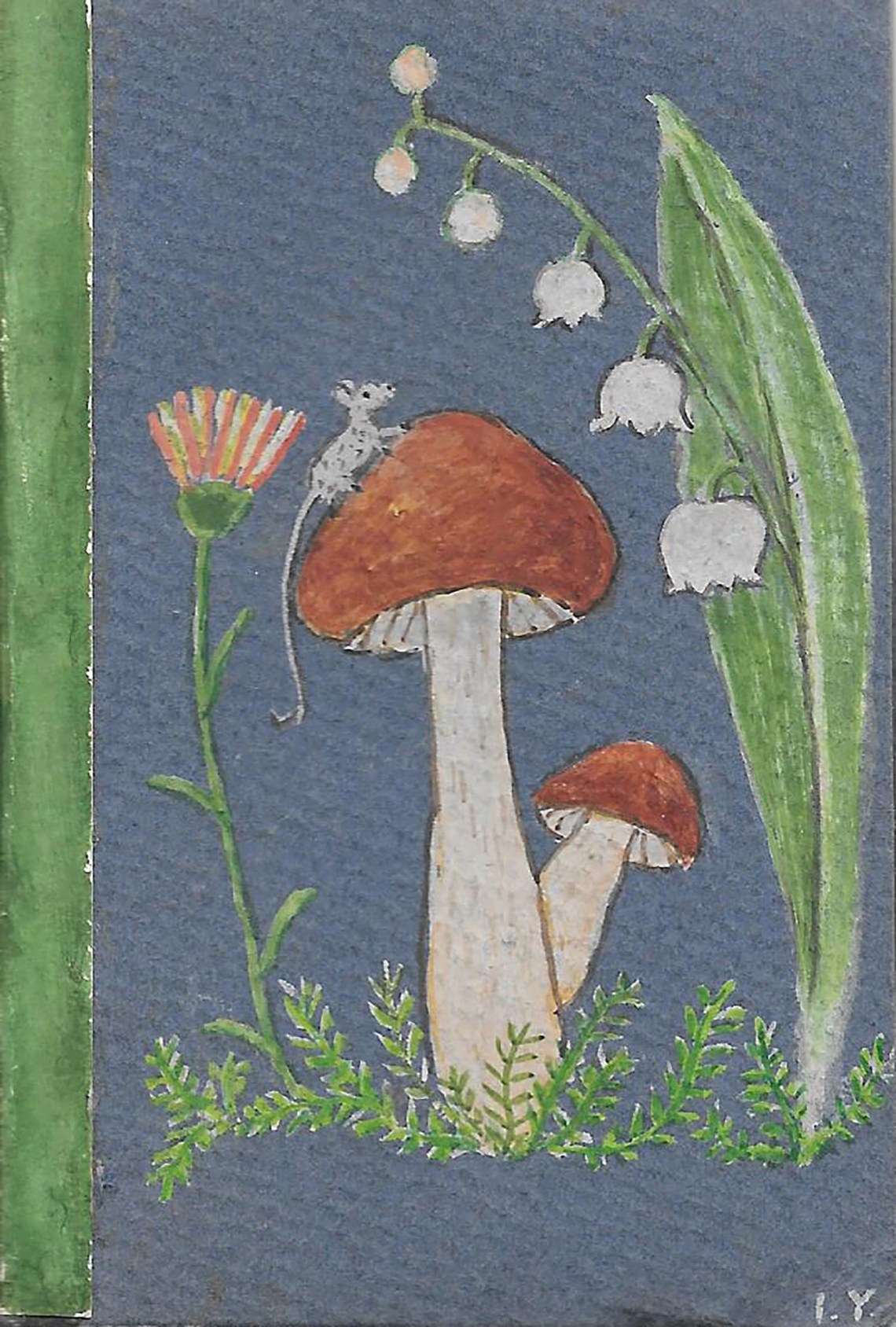

In Paris, Maria crossed paths with Irina Yusupova, Xenia’s only daughter and the wife of Felix Yusupov, once the heir to Russia’s largest private fortune—and another conspirator in the Rasputin affair. A woman of extraordinary beauty and even greater shyness, Irina painted from an early age, her work ranging from dreamy watercolors to booklets filled with flowers, mushrooms, and imaginary creatures. After evacuating aboard the British battleship with the rest of the family, many of whom would never forgive Felix for the Rasputin plot, in 1924 the Yusupovs opened their own fashion house in Paris, IrFé. It caused a furor even with the jaded Parisian public, becoming known for its artistic use of color, fusion of Russian and Oriental styles, and trend-setting slim silhouettes. But, like Kitmir, IrFé closed within a few years, unable to survive the Depression and the owners’ lack of business skills. They lost what little remained of Felix’s fortune, but their much-gossiped about marriage lasted for more than half a century. When Irina died three years after Felix in 1970, she was buried in the same plot with him and her in-laws in a cemetery in Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois, south of Paris.

Victoria

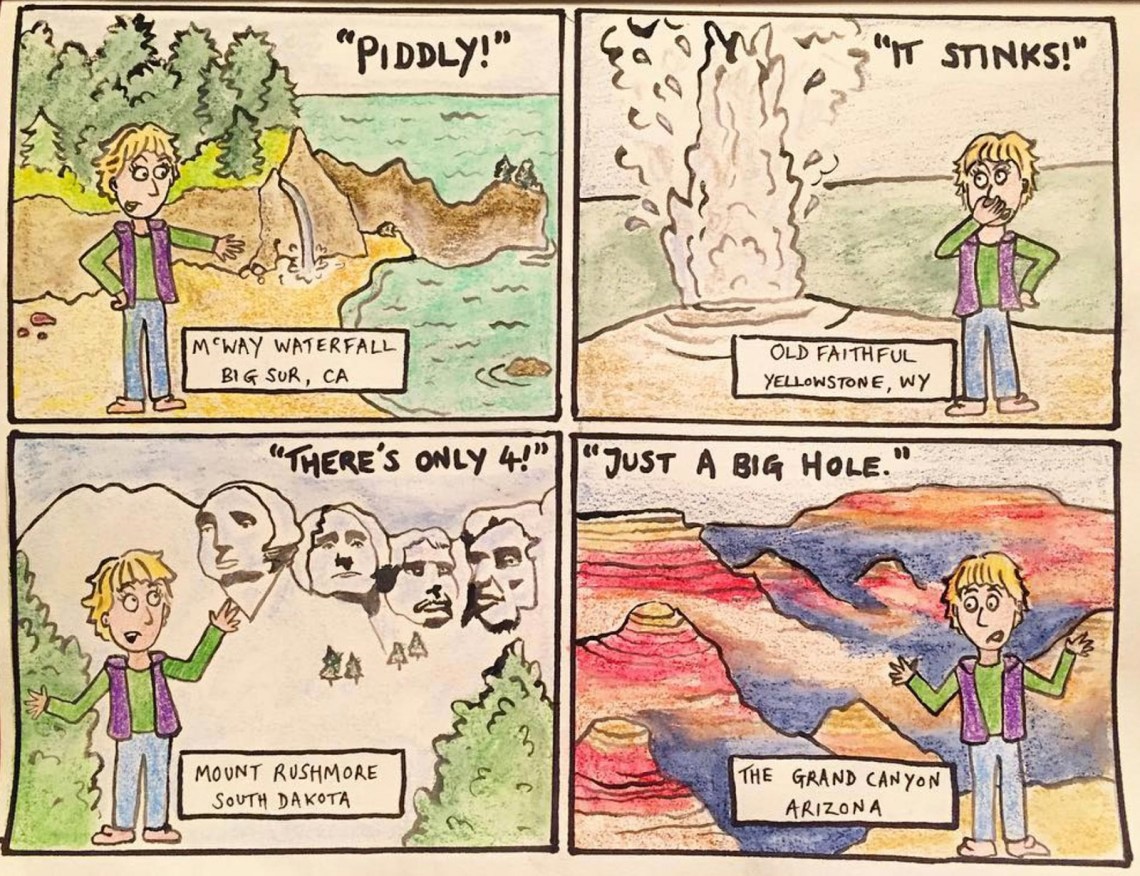

Some five decades after her great aunt Irina’s death, Victoria Galitzine spent hours in her family home in Sussex, England, looking through Irina’s booklets filled with flowers and mushrooms in her mother’s family archive. Today, in a small coastal town in northern California, Victoria keeps alive the family tradition of hand-drawn cards, cartoons, and nature painting. Victoria learned to doodle from her father, an amateur cartoonist and artist named Emanuel Galitzine, who held her on his lap as he sketched. Her mother, Penelope, also paints. After majoring in marine biology, Victoria worked for a conservation nonprofit in Santa Cruz, California. She then quit her job to pursue art. A “nature nerd” with a beehive and chicken coop adjacent to her studio, Victoria paints birds, trees, flowers, and mushrooms with the precision and perspective that, in typical Romanov fashion, suggest a depth of perception beyond that of a casual observer’s. In Victoria’s rendition, living things come across as vivid portraits rather than just species. Her work has been exhibited in several local galleries.

Andrew

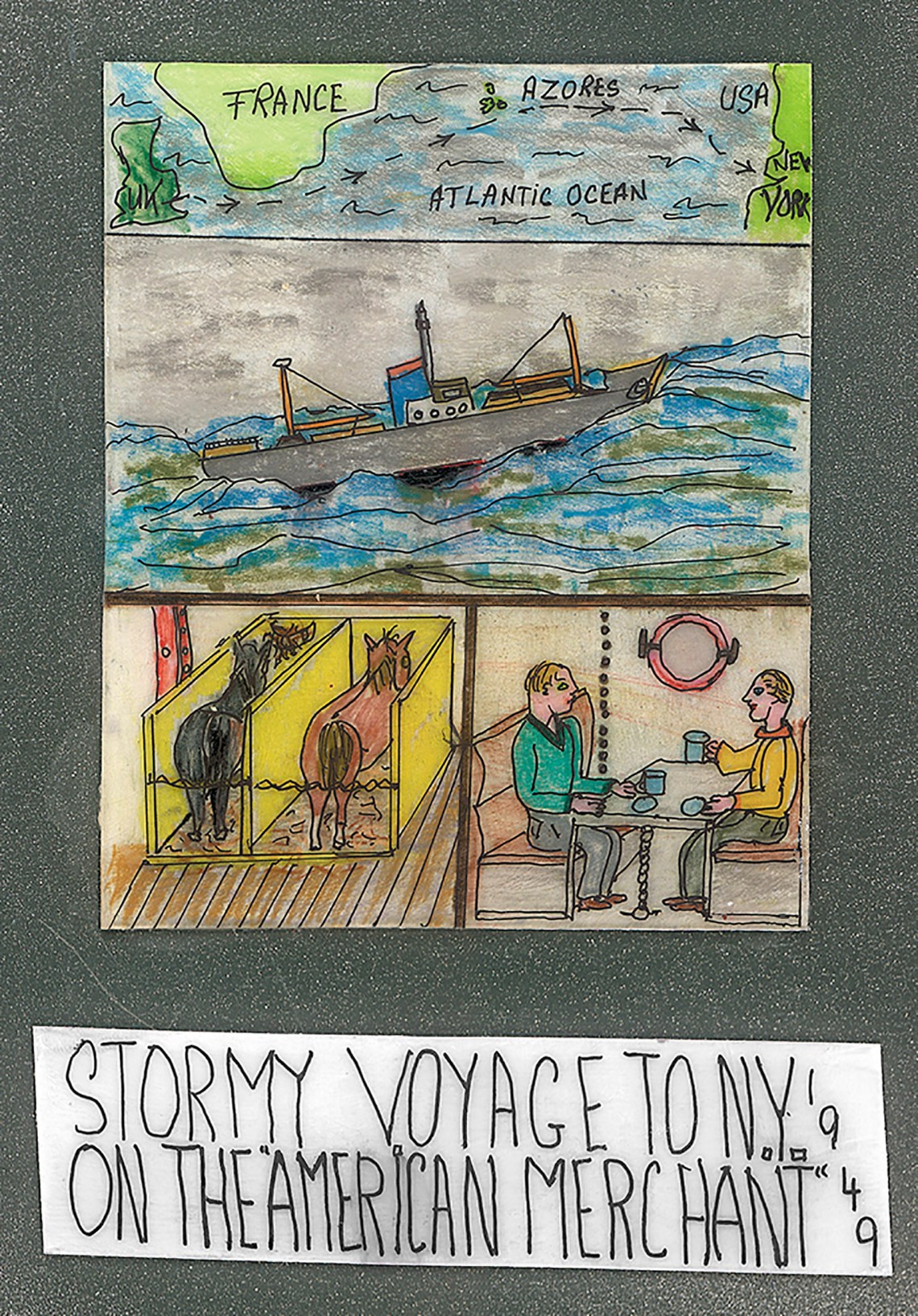

Victoria wasn’t the first Romanov artist to settle permanently on the California coast. In 1949, having served as a lieutenant in the British Navy during World War II, Andrew Romanov, a grandson of Xenia and Sandro, decided to leave the old world for good, arriving in America with just a few hundred dollars to his name. Working in shipping, import-export, and carpentry, he also began painting on Shrinky Dinks, plastic sheets from children’s activity kits that shrink when baked in the oven. Vibrant, folksy, by turns lyrical and tongue-in-cheek, the naïve style of Andrew’s art invokes the Russia of his exiled parents, his strange childhood in Frogmore Cottage, a “grace and favor house” on the grounds of Windsor Castle, and his life in America. He has exhibited in many galleries, published a pictorial memoir, The Boy Who Would Be Tsar, and, at ninety-five, is the oldest living descendant of Tsar Nicholas’s family. In 1998, he went to St. Petersburg to bury the remains of his great great uncle and his family.

Rostislav

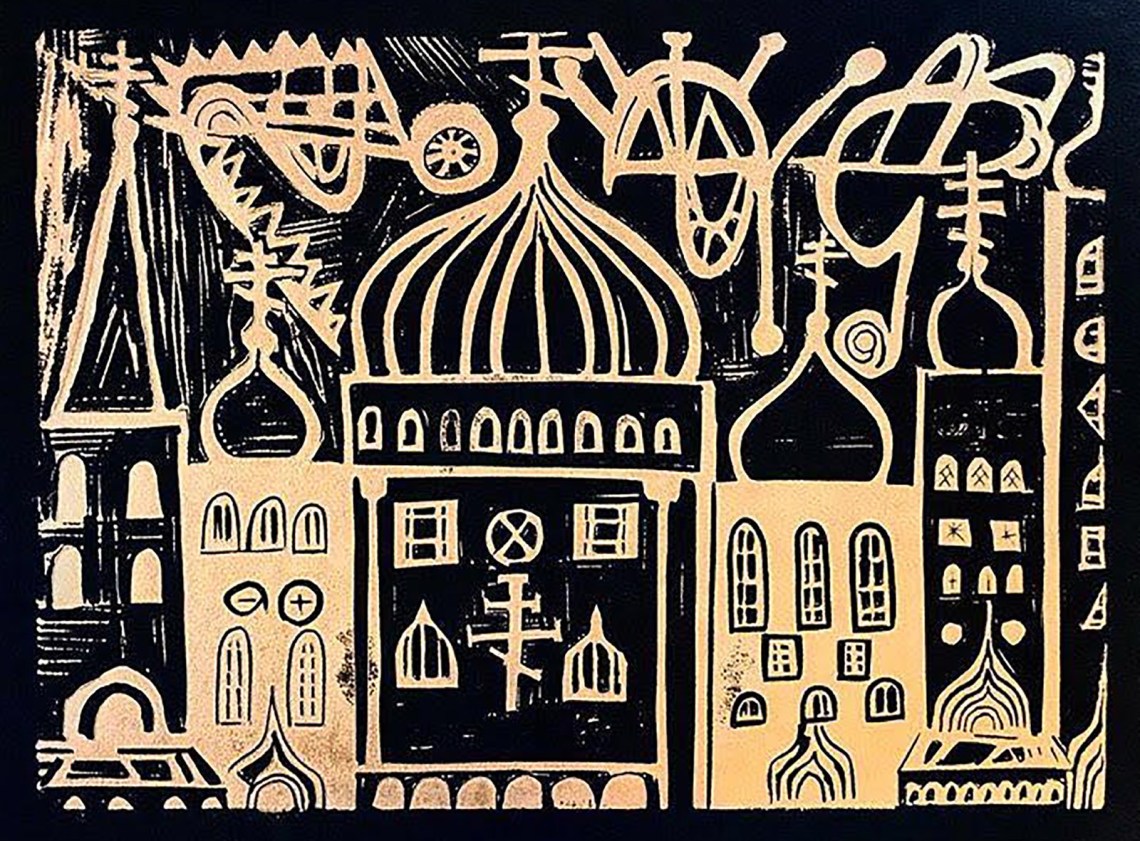

Also at the 1998 funeral ceremony, filled with apprehension and hope as the Romanovs and post-Communist Russia acknowledged the ghosts of their past, was a thirteen-year-old Rostislav Romanov, great grandson of Xenia and Sandro. Like most Romanov descendants, Rostislav arrived in a country he had never seen, and that generations of his ancestors had managed to keep alive only in his imagination. He fell in love with Russia immediately, instinctively recognizing the folk art, the old wooden houses, the churches, and the songs of the Old Believers: “my soul felt at home,” he said. When, a year later, his father died unexpectedly, Rostislav began to “paint his feelings,” as his art teacher had suggested.

Today, a fully-fledged artist with several international exhibitions under his belt, he continues to draw inspiration from the physical world. He has lived and worked in Russia, and travels there frequently. On July 18, 2018, along with a group of his relatives, he will be in St. Petersburg at the centenary memorial service for his murdered great great uncle Nicholas and his family. To Rostislav, Russia means not tragedy but “soul, friends, and beauty.” One can only hope, as the somber anniversary of July 17 is commemorated, that Russia, where tragedy and beauty have so often walked hand in hand, lives up to its people’s high expectations for a more hopeful future.

The author would like to acknowledge the cooperation and assistance of Romanov family members, art collectors, and art institutions in compiling the information and images for this essay.

An earlier version of this essay misidentified King George V as Maria Feodorovna’s brother-in-law; he was her nephew.