Jazz Standard on East Twenty-Seventh Street, between Park and Lexington, was a hell of a good club, my favorite in Manhattan. This is saying a lot, because there are several fine jazz clubs in New York, the undisputed jazz capital, most of which are barely hanging on today, just as the Standard was, their owners praying that the Covid-19 vaccine will finally bring back the city’s nightlife. It all became too much for the Standard’s owners, who announced on December 2 that, in view of lost revenues and a stalemated rent negotiation, they were forced to close the club.

The Standard was laid out beautifully, rows of tables set perpendicular to the bandstand, a comfortable bar near the entrance, and what felt like an entire space of its own stage left, where well-connected (or just fortunate) patrons could spread out a little at their tables. The sound system may have been the best I’ve heard in a small- to medium-sized room. The menu, barbecue and soul food from the attached Blue Smoke restaurant, was reason enough for a night out.

Most of all, Jazz Standard was a true club, a place to watch and listen and connect. I was never a regular but always felt like one, so easy was the mingling of staff and customers and musicians. Between sets, one could hang at the bar and overhear, say, the great pianist Cyrus Chestnut discuss a recording project, until you worked up the courage to join in the talk. Scan the audience and you might well recognize a celebrity, a rock star in mufti, a renowned dancer and choreographer, there for the same reason you were. The bookings were varied in everything but the exceptional level of talent. It could be Dr. Lonnie Smith one night, Louis Hayes the weekend after, followed by the Maria Schneider Orchestra, punctuated by an evening with the now-departed blues legend James Cotton, not too far off from having released his triumphant final album. And now Jazz Standard is dead, too, killed by pandemic economics.

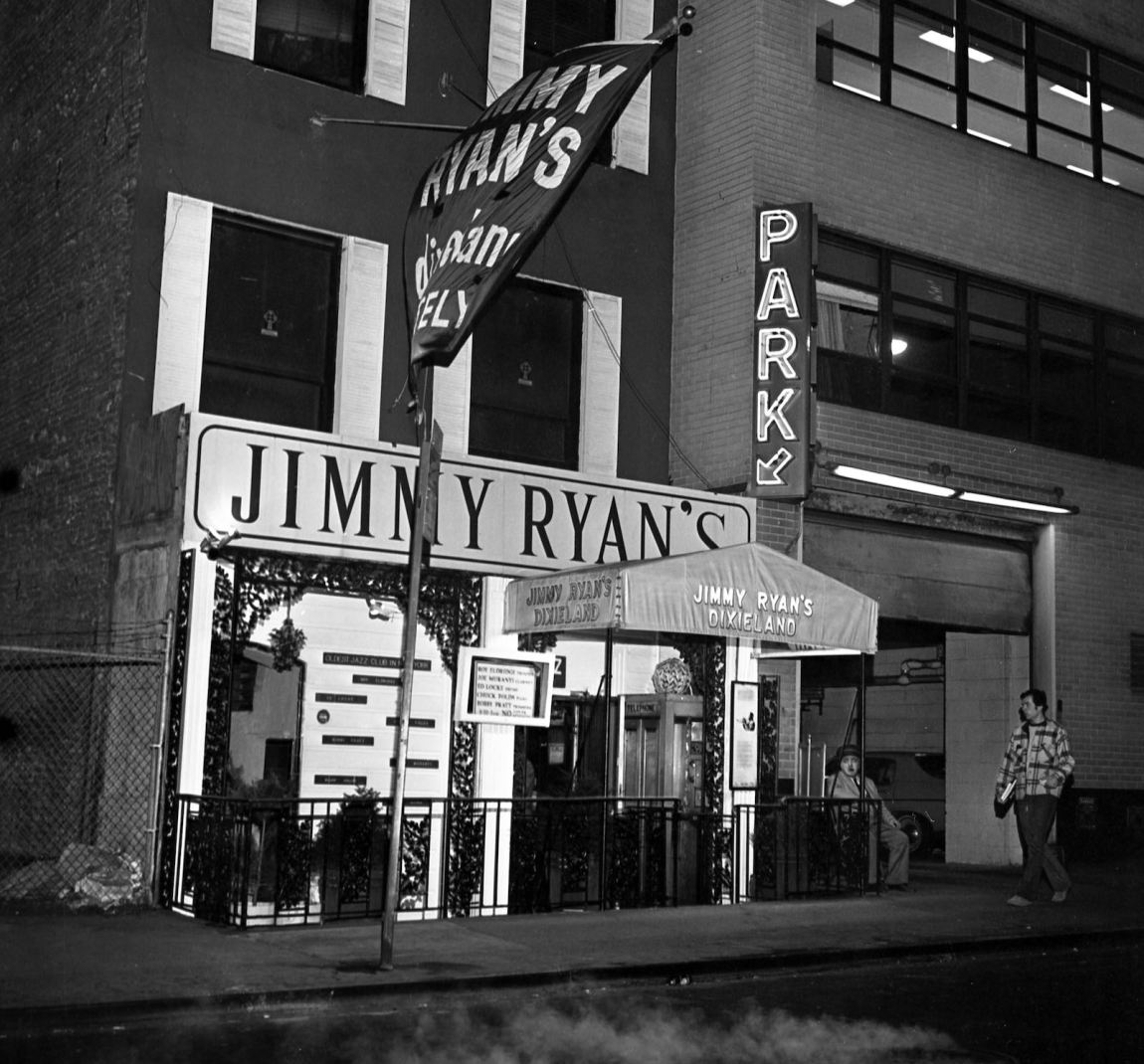

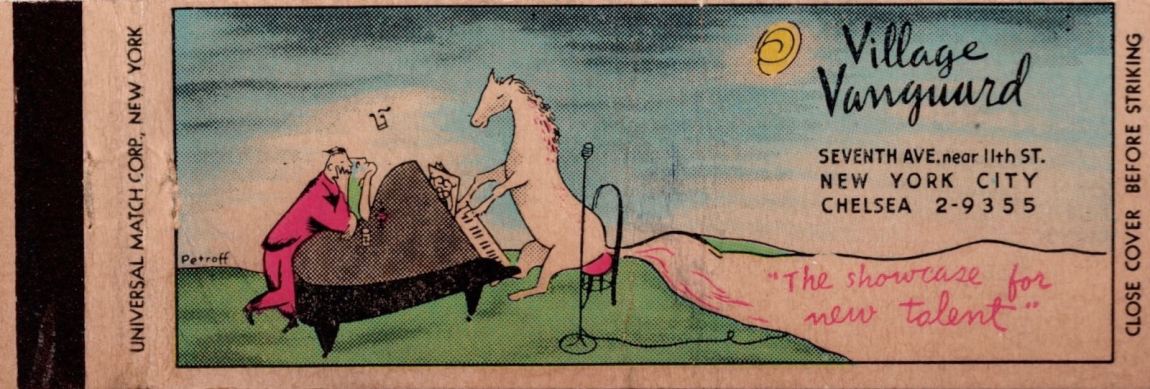

With jazz no longer enjoying the mass appeal it once did, it’s unlikely that the club will come to be known as a legendary venue; few if any of the remaining clubs will, except for the long-mythic Village Vanguard and perhaps the Blue Note on Third Street. I am just old enough, though, to have gratefully experienced the tail end of another era. Two blocks over from where I once lived on Eighth Street, at the famous impresario Barney Josephson’s The Cookery in the early 1980s, I got to hear the reemergent but undimmed old blues star Alberta Hunter team up with a special guest of hers, Eubie Blake, on what had been Blake’s big hit with Noble Sissle from 1921, “I’m Just Wild About Harry.” Maybe ten years earlier, I’d heard the trumpeter Roy “Little Jazz” Eldridge perform at Jimmy Ryan’s, the self-advertised “oldest jazz club in New York,” a trad venue at the heart of the bebop club world in the 1940s and 1950s that had relocated to Fifty-Fourth Street, two blocks up from its original home.

The doorman at Jimmy Ryan’s, the short, stocky Gilbert J. Pincus, was known as the “Mayor of Fifty-Second Street” back in the day, when several places hired him as greeter—though the musicians called him “Yiz’ll,” for his habit of telling crowds that were blocking entrances, “Yiz’ll have to move on.” Jeff Gold’s Sittin’ In, a book of photographs of, and memorabilia from, the club scene in its pre-1960s heyday, includes a shot of a much younger Yiz’ll, thirty years before I saw him, barking for customers outside another famous Fifty-Second Street spot, the Three Deuces.

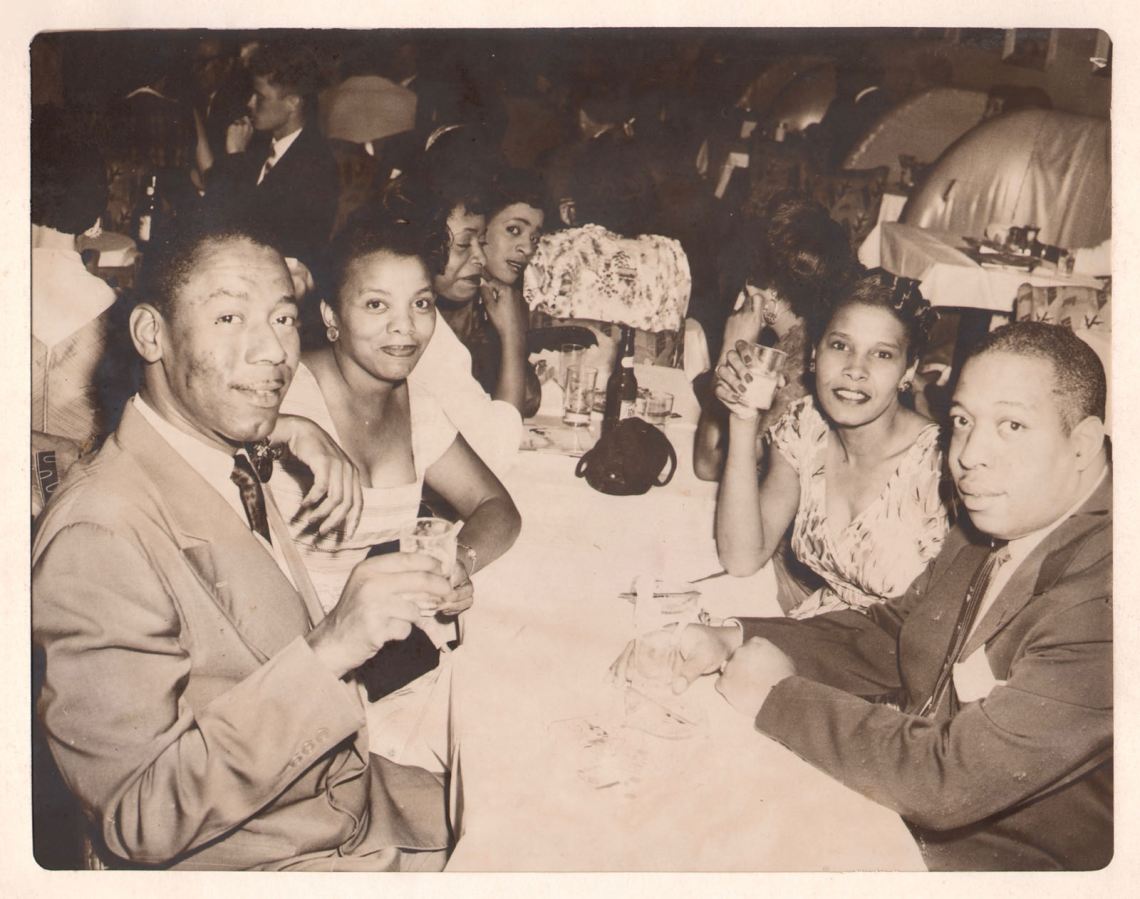

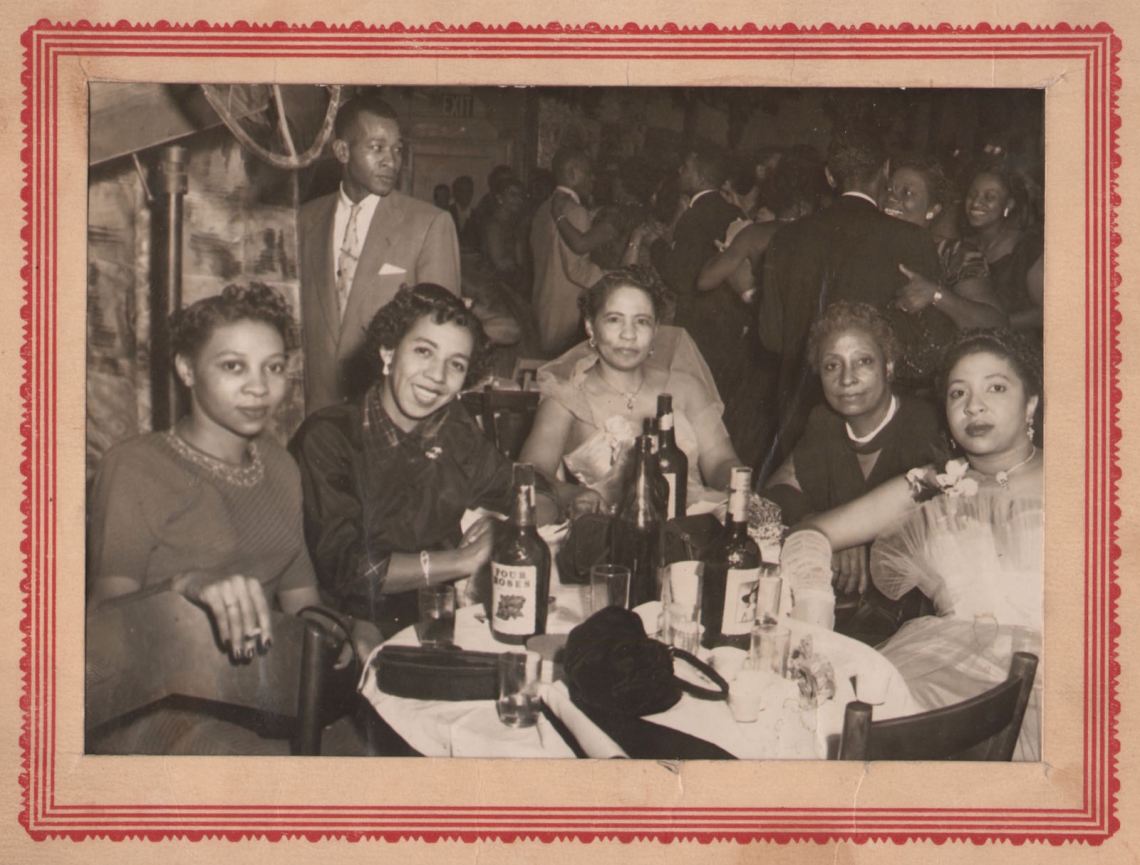

In the wake of Jazz Standard’s passing, Gold’s book allows the pleasure of revisiting those older places, and dozens more besides, from the era when jazz clubs were in their prime. A premier collector of jazz memorabilia, as well as a historian and archivist, Gold was wading through another collector’s holdings when he stumbled upon a cache of customer photographs from numerous clubs. They had been taken by the clubs’ house photographers—developed and printed on the spot, ready in time for the patrons to buy them for a dollar apiece as they headed home: an inexpensive keepsake from a special night on the town.

Here, Gold saw right away, was documentation of a virtually unknown facet of jazz history: the audience appearing not as rapt, passive listeners but as patrons having fun, showing off a little. These were pictures, he writes, that “turn the camera around.” They show mostly couples out on double or triple dates, but there were also businessmen treating clients and their wives, uniformed soldiers on furlough and sailors on shore leave with their girls (some of them uniformed as well), celebrants in black tie and gowns, relaxed regulars in shirtsleeves and porkpie hats, and, in one instance, a party of women from the Progressive Social Club (established in 1946), dressed to the nines, standing in front of the small bandstand at Small’s Paradise in Harlem. There are plenty of cigarettes and liquor, including what look like at least three quart-sized bottles of whiskey, Four Roses most prominent, on the table before a group of mostly middle-aged women at Harlem’s Celebrity Club, who, with one exception, wear just about the only severe-looking faces in the entire book.

Although New York clubs contribute the largest number of photos, the collection embraces ten other cities on both coasts and in the Midwest. Together with a smattering of posters, flyers, postcards, and matchbook covers from Gold’s collection, the images testify not just to jazz’s popular peak but to a now-distant optimistic moment of promise in American life.

As ever with jazz, as in America, race figures large in the picture. Back then, unlike now, the jazz audience was largely Black, as are most of the customers in these pictures. Aficionados argue endlessly about why this has changed over the decades, some claiming that African-American audiences abandoned jazz, others that jazz abandoned African Americans. Gold’s club photographs, though, attest to an earlier and very different social dynamic. In the beginning, jazz clubs in New York and elsewhere conformed to Jim Crow segregation. Most notoriously, the Cotton Club on 142nd Street, which was run by the mobster Owney Madden and became the showcase for, among others, the Duke Ellington and Cab Calloway orchestras, admitted white patrons only and actively demeaned Blacks in other ways, such as by the billing of Ellington’s orchestra as the “Jungle Band.” For the musicians, the exposure was irresistible, especially on radio broadcasts from the clubs, but a price was exacted in pride. (Forced to close after Harlem’s race riots in 1935, the place reopened on Broadway and Forty-Eighth Street and ran for another five years, still strictly segregated.)

There were important exceptions, like Small’s Paradise, racially integrated from the start, in the 1920s, and a favorite spot for celebrities such as Joe Louis and Tallulah Bankhead. The leftist Barney Josephson started his celebrated Café Society in Sheridan Square in 1938 as a purposefully interracial political cabaret–cum–jazz club, where John Hammond served as the chief talent scout and where, in time, Billie Holiday would close her sets with Abel Meeropol’s “Strange Fruit,” to a hushed, racially mixed audience.

The divide truly began to close, though, after World War II, when the bebop boom that began at Minton’s Playhouse and other Harlem clubs took over much of Fifty-Second Street, then spread elsewhere in Midtown and down to Greenwich Village. White and Black customers alike headed to the Royal Roost, a chicken and jazz joint that the DJ “Symphony Sid” Torin helped turn into a bebop headquarters, dubbed “the Metropolitan Bopera House.” There, you might first hear Charlie Parker wail, only to have Parker then join you at your table for a snatch of conversation—following which the club would present you with an autographed picture all your own. At Birdland, a three-hundred-seat venue named in Parker’s honor that opened in 1949, you might look over at the next table to see two sharp, slick-haired white guys trying to nestle with a pair of African-American women, right next to the posing celebrity and club regular Marlon Brando.

Gold includes some choice interviews in his book, including one with Quincy Jones, who recalls how, at the jazz clubs on Fifty-Second Street in the early 1950s, race was present as a reality, but racism did not enter in; he says that this was true not just among the musicians but for the audiences, too—people got along, in “a place of community and pure love of the art.” (“Racism would have been over in the 1950s if they listened to the jazz guys!” he declares.) In another interview, Sonny Rollins says much the same:

Advertisement

That’s one of the things that jazz musicians never get credit for, it was such an integrated scene. We never really get credit for that. Everybody else gets credit—or blame, if you want to put it like that—depending on your point of view. But, you know, for that, jazz was really where the racial barriers were broken down heavily. I’ve always thought that.

These images bequeath a rarely published view of Black American middle-class life at mid-century: relaxed, elegant, and urbane. You come away sensing that the racial merging described by Jones and Rollins was more imperfect than they let on, as in one photo from the Downbeat Club on Fifty-Second Street, in which brash whites stand up front, grooving with the beat, with African Americans to the rear, and one expressionless Black face stares directly into the camera. You also come away struck by how singular this postwar moment was. Finally, though, you come away refreshed by the spirit of what once was, a spirit that rebukes and shames where we seem to be today.