The restaurant reeked of vegetable oil and frying garlic, and the grease settled on the plastic surface of every table and chair in the space. In the back corner, my mother, age twelve, barely tall enough to reach the top of the counter even with a step stool, tapped away at a faded yellow cash register. Her eyes, filling with tears, darted from the faint green numbers on the display to the hostile face of the customer in front of her, as she struggled to hold the orders in her head. The man hovered, knuckles rapping the counter.

“Where’s my change?” They were always like this, her father had warned her. Calculating and cold, waiting for the first chance of a slipup to scam the family business. She trembled as she quickly handed over the bills, certain she’d made a mistake with her calculations.

My mother recounts this memory in Mandarin. It’s as though English would do it injustice—it couldn’t capture the disappointment of failure to quite the same degree.

When she was eleven, her family moved from Fuzhou, capital of southeastern China’s Fujian province, to Union City, New Jersey. There were few Chinese immigrants at her school, so she kept to herself, idling away her hours at home with cassette tapes and television. When she wasn’t working, she hung around her siblings, sharing secrets, playing on the cracked floorboards of their two-bedroom apartment.

By force of habit, she still frequently switches languages, transitioning between the two with a virtuosity I can’t match. Though she’s fluent in English, she still has stories that she can only tell in Mandarin. There’s just something beyond the vocabulary of a language that gives words their meaning, she’s explained to me.

“I’m sorry I don’t know how to say this,” she often says, mid-conversation, when she’s no longer able to express herself in English. Sometimes she’ll switch back to Mandarin to finish her story. More often, she’ll drop the rest and run off to her errands, leaving traces of her girlhood hanging in the air between us.

*

My wet fingers cut easily on lotus leaves, so I tried to work carefully, packing the wet rice into a cone shape. I awkwardly tied the rice wrap together, to complete my zòngzi with a piece of white string. The other students had shaped theirs into golden ingots or snow cones, but mine looked closer to a potato. Behind me, parents were rushing to gather the sticky-rice wraps, bamboo steamers flying across the wooden tables.

I’d watched the older kids before. I’d seen them assemble zòngzi for the Dragon Boat Festival, but this was the first year I had to prepare the sticky-rice wraps myself. Outside the kitchen, little children ran past the classrooms where the language classes were held. Parents yelled at them to slow down as they passed, clutching empty potato chip bags in their tiny fists.

I started attending Chinese school every weekend before I’d even enrolled in kindergarten. Unlike the kids at my elementary school, who made fun of the salted jellyfish I brought in for our class potluck, everyone here shared a cultural ancestry and understanding. We traded stories of our discomfort with language—how our parents spoke English at home yet expected us to understand Mandarin, as though all we needed to achieve fluency was weekly vocab practice.

Normally, Saturdays were filled with hours of lectures and written assignments, but not today. We filed into the cafeteria, carrying trays of lotus-wrapped sticky rice for the Dragon Boat Festival. I spoke to my Chinese teacher as we walked down the hall, my Mandarin thick and clumsy with my American accent. But she didn’t rush me when I stalled, searching for the right words. Unlike my mother, she didn’t correct me every time I used the wrong tone.

The festival began with a speech from our principal, thanking all of the parents for volunteering to help preserve Chinese culture in New Jersey. He praised them for giving up their weekends to drive their children to lessons, for staying to judge speech and calligraphy competitions, for teaching classes and preparing food. He then asked if the students had anything they wanted to add. I considered raising my hand. But I couldn’t possibly speak in front of the whole school—not with my broken Mandarin. Not with my mother watching.

*

I remember the sign well, the bright, slanted “East Asian” typeface, bold and angular: “First Wok,” hanging above a storefront decorated with paintings of Chinese junks. Sometimes, when we were busy on the weekends, my parents would order takeout from the rundown restaurant, referencing dishes numbered in bright red ink: beef with broccoli, fried rice, green beans with garlic sauce.

Advertisement

My mother pointed at the menu’s “No MSG,” proudly proclaiming that we were eating from a “good” restaurant. When I pressed her on whether her own family’s restaurant had used MSG, she was hesitant to answer.

“Everyone used some MSG. We tried to use less,” she said. “The food would be so bland without it.”

Chinese food became an easy target for the mistrust of the new, exotic immigrants moving to American cities in the late twentieth century. My mother had to grow up in the shadow of this hostility. She recounts those days with a mix of anxiety, ennui, and fondness. Members of a neighborhood gang would often bully her on the streets near her home, make fun of her accent, even spit at her. Still, it wasn’t all bad—she often spent afternoons learning recipes from her father, getting lessons in carving roast duck or gutting a fish.

After my family moved from New Jersey to Queens, New York, I visited the old restaurant where my mother used to work. It was being sold to a different Chinese family after years of disuse. I marveled at how familiar the golden signs looked from the photos she had shown me, and yet how different the crumbling interior was from my imagination: the cracked linoleum tiles on which she’d stood for hours each day, passing food to customers; the creaking wooden staircase where she and her three siblings played after school; the plastic stools she squatted on between shifts.

I imagined how different she and her family must’ve looked from all of their neighbors, their fear when they first moved into the apartment, the hope that one day she might find a home in this new, strange place.

*

As the Covid-19 pandemic spread in the United States, safety measures and fears of liability forced nearly every university in Massachusetts to empty their grounds. This was how, a year ago, the newfound independence I’d created and cherished in my preceding three years at college came to an abrupt end. I tearfully parted from my co-op in Cambridge, and soon found myself in my family’s cramped apartment in Queens.

In the first few days, I felt as though I’d fallen back into my childhood. My mother was suddenly in charge of the house once again, barging into my room at night to remind me to do my laundry. My father pelted me with questions about when I was getting married and shut off the Internet at midnight to force me to bed. Back in Cambridge, I’d led communal meetings with my housemates, served as an academic adviser in my department, and taught workshops to high school students in the Boston area. Here, I was still a child, unable to make even basic decisions for myself.

I described this to my therapist over a teleconference. In my ten years of therapy, she was the first Chinese therapist I’d seen. With her accent and frequent use of proverbs, her mannerisms were familiar. In our past sessions, she’d shared her own struggles with parenting. Like my mother and father, she tended to be overprotective of her child, to the point where her daughter left home a month into quarantine.

She reflected on the irony of the situation—advising me in my relationship with my parents while she was also working on navigating her relationship with her own daughter. One suggestion she made was to redirect my frustration into productivity. She advised me to time my working hours, to track my mood—as if bullet journals were all I needed to regain my sense of agency and identity. Still, I didn’t have any better ideas, and a muted peace with my parents was better than our constant brawling.

Connecting was complicated. I found it difficult to talk with my mother. Historically, her approval always arrived deadpan, her displays of physical emotion performative; I could hardly communicate my anxieties to her in English, let alone in Mandarin. It wasn’t for lack of trying—my mother frequently encouraged me to speak with her in Mandarin, but I was always self-conscious of my American accent. I was a fraud, calling myself Chinese when I could barely recognize the most common idioms. Even when I was trying my best, my identity still felt like a mask, as though I was pretending to be someone I wasn’t.

*

It was back in middle school when my mother found me watching YouTube tutorial videos for cooking fried rice. She remarked that the recipes online were inauthentic, cheap imitations of Chinese cuisine adapted for an American palate.

“They’re turning you soft,” she told me. “You’ve got to learn the real deal.”

Advertisement

To her, the real deal meant cleaning the offal from the carcass of a chicken. It meant understanding how to adjust flavors between bouillon, black sugar, and garlic, and being able to select the right combination of vegetables and meats so that the dish was perfectly balanced.

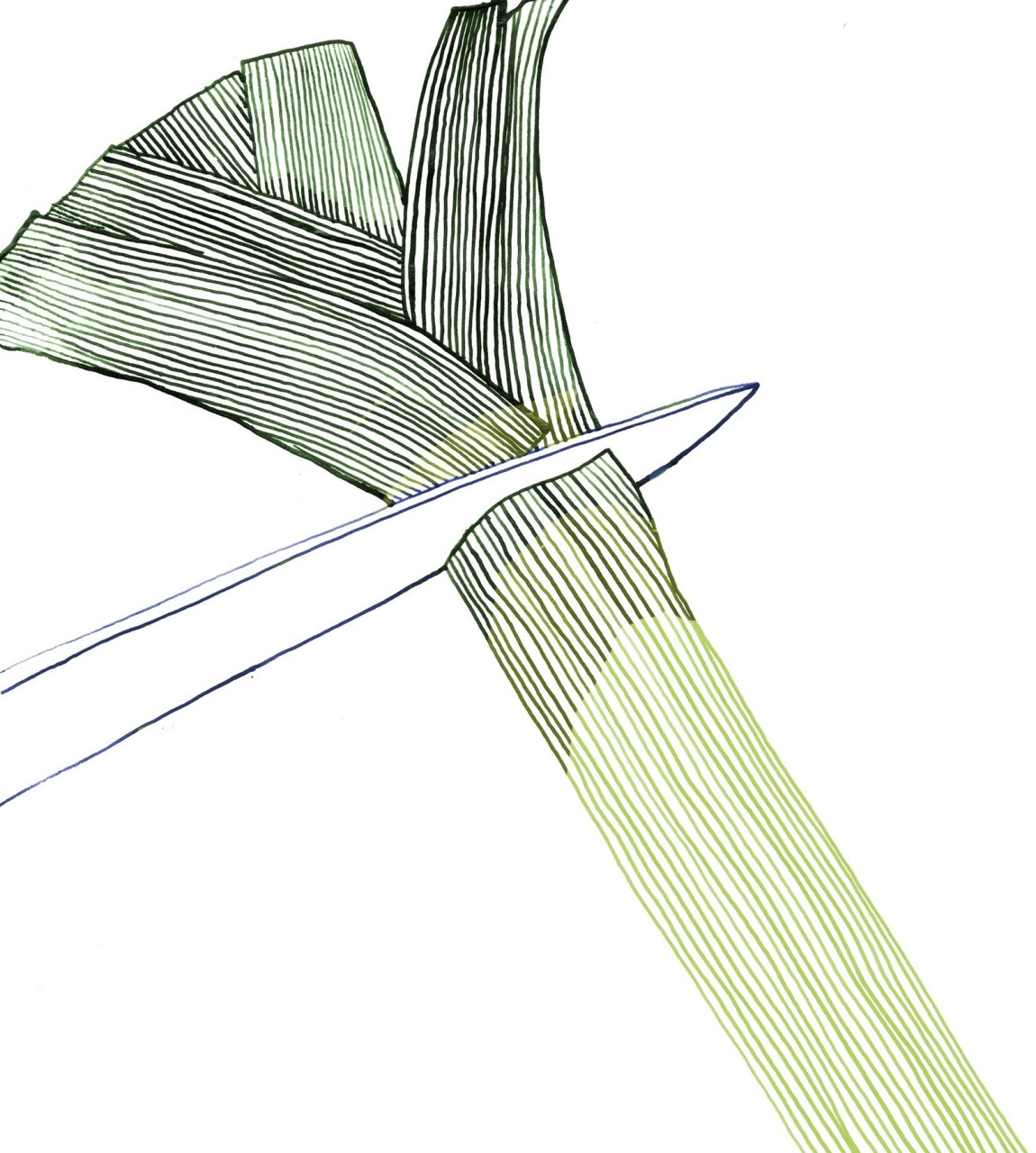

Beyond that, my mother was hardly impressed with my knife skills. Basic cooking requires the ability to dice onions, and even by the time I was in college, I was still terrified of cutting myself. Recently, my mother stepped into the kitchen as I was preparing dinner. She fretted over my erratic technique and pushed me aside to demonstrate how to curl my fingers, to tuck my thumb. I imitated her motions, feeling the smooth contact of the blade against the cutting board.

Her vegetable cubes were much more even than mine, though she reminded me that she’d had years of practice in the broiling back kitchen of the family restaurant. Her movements were brisk and efficient; she handled her cleaver as if it was an extension of her arm. I was amazed at how her eyes would not water when she cut the onions, how she held her face completely expressionless.

One of the dishes I wanted to make was steamed bass, a staple of many Chinese dinner tables, but a dish I’d never had to prepare on my own before. As I stared at the fish on the cutting board, I half expected my mother to stand over me to guide me through the motions. Instead, she sat at the kitchen table, texting her friends.

“Aren’t you going to help?” I asked her.

She waved her hand. “You can do it on your own.” I turned back to the cutting board, following the motions she’d taught me. I knew how she ran the edge of a blade against the fish skin to remove stray scales, how she combined soy sauce and sesame oil to achieve the perfect savory balance, how she topped it all off with a sliver of ginger. Seeing the striped bass emerge from the steamer was like watching my mother reveal her dishes from a lifetime of the dinners she served when I was growing up. Only this time, I was the one revealing the centerpiece. As my family settled around the table for our meal that evening, I offered my mother first cut of the fish. She nodded to me, neither of us saying a word