This story was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center and the Economic Hardship Reporting Project. A Spanish translation was published by Gatopardo.

In her sleep, Daniela works just as she does when she is awake. In her dreams, she puts on layers of protective gear: the plastic gloves, the cloth gloves, and the metal glove. Then she grips the knife and begins to cut chicken. Sometimes she wakes up covered in scratches from having worked through the night.

Daniela, forty-nine, is a short, powerful woman, her face round and expressive. Her hands are often clenched, her fingers curled against her will, a side effect of years of repetitive-motion labor. She has worked for the meatpacker Tyson Foods for twenty-one years in one of their largest plants in Arkansas: first in slaughter, then in packing, and finally in white meat debone, where she cut wings for $17.50 an hour, ten hours a day, four to five days a week.

She divides her work life into her undocumented years working under a fake name and her documented years working under her real one. (Daniela is a pseudonym.) She migrated to the US from San Marcos, Guatemala, in 1998, when she was twenty-four, and gained citizenship when she married at thirty-six. She met her husband at the plant, where he worked washing box lids. He was thirty-two years her senior, from Texas. Daniela described him to me as kind, quiet, thoughtful. In their wedding photo, which hangs above a small dining table in her trailer, they are dressed in old-time Texan formalwear. On good nights, she dreams of him.

During the early months of the pandemic, the plant had a labor shortage as workers became infected, and Daniela was doing the work of two people. “Your hands fall asleep,” she told me, describing the ten-hour days. On June 12, 2020, her body began to ache at work and she went to the nurse, who told her to go back to the line or she would lose “points.” Tyson’s attendance policy is a points system; if workers lose too many points, they are automatically fired. Workers who tested positive for the coronavirus could stay home without docking points, but Daniela said that the nurse didn’t offer her a Covid test. At the Tyson plant, supervisors posted a sheet each day with the number of positive Covid cases reported but without the names of the infected workers. “We realized who had Covid when they disappeared.”

When she got home that night, she was not feeling well. Within two days her husband couldn’t breathe. Like many workers, her husband, who was eighty, knew that he likely had Covid and was going to die. Before the ambulance picked him up, he told his wife to take care of herself if he didn’t return, keep fighting, and return to her country if his employer gave her money—the $1,500 that workers called the “death check.” He was hospitalized.

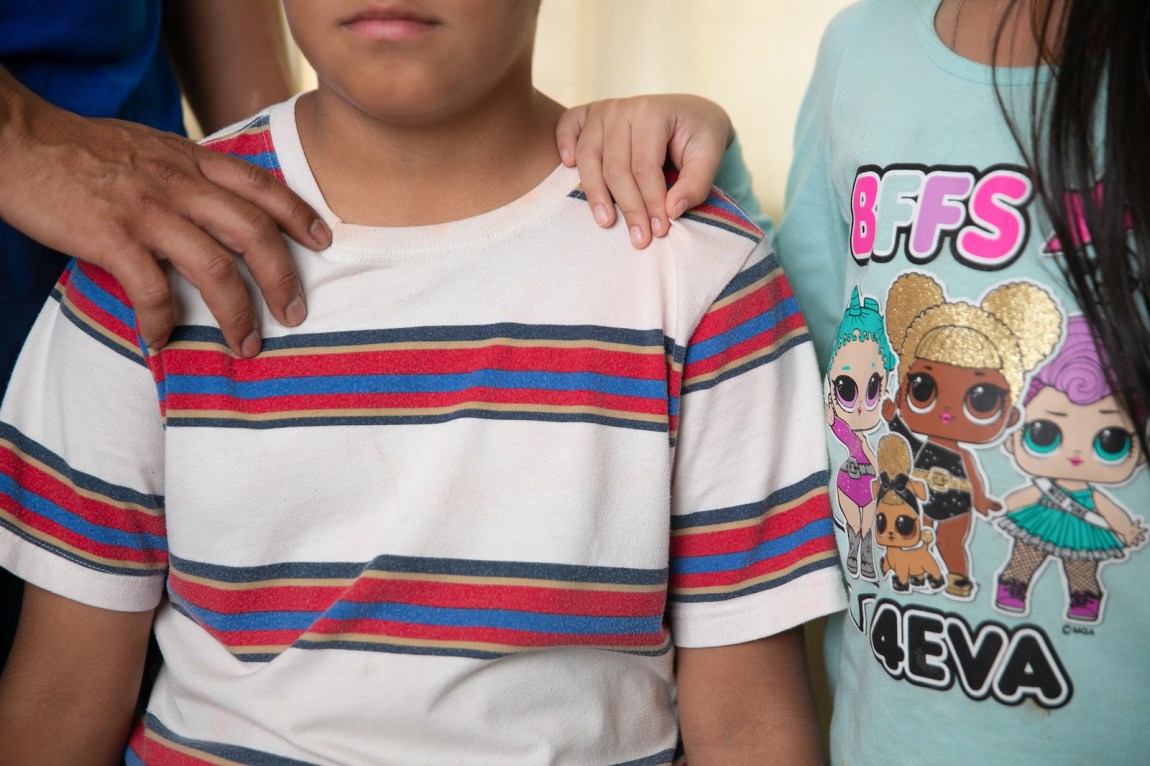

On June 16 Daniela was notified of his death. His body spent two days at the funeral home because she was in quarantine and couldn’t arrange the funeral. His health insurance paid part of the hospital bill, but she got a bill for $3,000 that she couldn’t pay. Between her husband’s medical expenses and the funeral she spent $14,000. In total, she received $4,500 from Tyson. She stayed in Green Forest and kept working at the plant to pay off her debts. But she felt lonely after her husband died and asked her fourteen-year-old niece in San Marcos to come live with her. “I tell her to study, that I don’t want to see her in Tyson,” she said, looking at her niece’s face peering out between the beige curtains of the trailer’s small window.

When Daniela first dreamed of her husband, he appeared to her sitting on the couch in their living room. “When you want to do something, do it,” he told her, “and don’t be afraid.”

*

Green Forest is a town of 3,000 people. If you visit the tiny cemetery there are dozens of tombstones dated 2020 and 2021 bearing the names of poultry workers from Myanmar, Guatemala, Mexico, Thailand, and the Marshall Islands. Daniela’s husband was one of the estimated 269 meatpacking workers who died of Covid nationwide during the first year of the pandemic. According to a memorandum by the House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (SSCC) in October 2021, Tyson reported 151 covid-related deaths, twice as many as any other meatpacker.

Tyson Foods is the largest meatpacker in the US and the second largest globally. Domestically it employs 141,000 people and operates 241 plants, including facilities in twenty Arkansas communities. The company often builds its plants in small, rural towns, becoming the main source of employment for residents, mostly immigrants. For undocumented workers, who are estimated to make up at least 14 percent of the meatpacking labor force in the US, companies like Tyson control their lives to such a degree that they are often afraid to speak about perceived labor violations.

Advertisement

It’s difficult to get Tyson executives to comment on labor issues, but in a 2000 interview intended for internal company purposes, Donald “Buddy” Wray, who had just retired as Tyson’s president, said that “without those employees from other countries that don’t speak English, we’d be out of business.” A spokesman for the company, Derek Burleson, told me, “Our position on immigrant and refugee team members is clear: we’re proud to employ immigrants from across the world and consider their contributions vital to our success. Numerous languages are spoken across our facilities, with up to thirty-five languages at a single plant. This diversity is our strength.”*

Arkansas is a “right to work” state, where laws ensure no individual can be forced to join or pay dues to a union. In 1944, when Arkansas legislators proposed the right to work amendment, it was with the express goal of making sure white workers would not organize with Black workers. Of Tyson’s plants in the state only one, in Dardanelle, is unionized. “We would rather run a union-free environment,” Leland Tollett, Tyson’s CEO from 1991 to 1998, asserted in another internal interview in 2000. “Our people are better off dealing with our company. We are fair people. And if we’re not fair people in something, we need to figure out how to make sure that those people do understand that we’re trying to be fair.”

Five Fortune 500 companies are based in Arkansas, with Walmart and Tyson Foods dominating the state economy and influencing legislation at the national level. Tyson (headquartered in Springdale) and Walmart (in Bentonville) have invested millions in parks, roads, museums, and other infrastructure in their modern-day company towns. When I drive to Springdale I take the Don Tyson Parkway and pass NGOs, businesses, and schools that have received funding from Tyson. Local media publish glowing articles about company profits and philanthropy.

This generosity is made possible by their history of paying low wages and treating workers poorly. After lobbying officials at the USDA to designate the meatpacking industry as “critical infrastructure” and its employees as essential workers, Tyson earned record profits during the pandemic, including nearly $2 billion of net income in the first half of 2022. The critical infrastructure designation allowed companies to exempt their employees from stay at home orders and social distancing requirements.

As of November 1, 2020, a “Class I” worker—Tyson divides its employees into seven pay classes—who had been at the company for at least ten years made $13.50 an hour. A worker in Class VII with comparable seniority made $14.95. When the pandemic began Daniela was in Class VII, but due to problems with carpal tunnel syndrome she was demoted to Class I earlier this year. (Tyson’s spokesman notes that the company has since implemented pay raises at some of its Arkansas plants, including one in Springdale where starting pay now ranges from $15.65 to $20.20 an hour.) Daniela is currently waiting for Tyson to agree to pay for surgery in both hands.

Plácido Leopoldo Arrue had worked at the Berry Street Tyson plant in Springdale for two decades before dying of Covid in July 2020. His widow, Angelina Pacheco, went to nearby Siloam Springs to visit a brujo, like her an immigrant from El Salvador, who promised to make Tyson “vomit money” to cover the costs of the funeral and medical bills. The shaman sacrificed a goat as part of the ritual. Ultimately Pacheco relied on family in El Salvador for donations to pay for the funeral.

When I visited her this past October, Pacheco, still mourning her husband, described him as “more dead than alive” even before he contracted Covid. Arrue had damaged his lungs in a chemical accident at the plant in 2011, in which 152 people were hospitalized for exposure to chlorine gas. Pacheco, who used to process poultry at Tyson and now works at Simmons, works in her sleep at night, like Daniela. “I wake up tired,” she said. “Tired and feeling like I am drowning.”

*

On April 10, 2020, a worker at a plant in Springdale took a voice-activated pen recorder to a meeting with human resources. José, who had worked at Tyson for ten years, transporting and opening the boxes of frozen chicken used to make nuggets, was given the recorder by an investigative video journalist for Al Jazeera early in the pandemic. (José is a pseudonym.) A runner, lithe and self-assured, José has often thought that in another life he could have been a journalist himself, and kept recording labor conditions at his plant, in defiance of the “ag gag” laws in Arkansas that criminalize entering a meatpacking facility to take pictures or videos with the intent of distributing them, effectively preventing whistleblowers from revealing labor violations.

Advertisement

His supervisor was at the meeting. “I am worried because I have four small children,” José told him. “It doesn’t matter if they are not going to school if I am here and can infect them.” José has told me that it was impossible to social-distance at work, and that the company had not provided workers with adequate personal protective equipment. At some plants, workers were asked to sew their own masks.

The supervisor responded by suggesting that José “didn’t want the plant to function” and, rather than address the risk of his becoming infected at Tyson, emphasized the risk of visiting the supermarket. The company line on the coronavirus was that it originated outside the plant, and that transmission within the factory happened because workers were irresponsible in their activities outside work. Workers at the same plant in Springdale sent me photos of a Christmas display that said BABY IT’S COVID OUTSIDE!

José pointed out that the incubation time of the coronavirus, several days, rendered the daily temperature checks almost useless at preventing its spread. “If we weren’t producing chicken there would be a lot of hungry families out there right now,” the supervisor countered. “Don’t think only of yourself and your children—think about your neighbors who don’t have stable employment like you and don’t have food stored.” When José pressed him for details about how the company would support workers who tested positive for Covid, the supervisor responded, “If Tyson stops producing chicken, hundreds of millions will die.”

At the time, the company and other meatpackers were lobbying the Trump administration to keep meatpacking plants open despite high Covid infection rates, arguing that closing plants—which could have saved workers’ lives—would lead to a national meat shortage. But José knew from reading the news that Tyson had been increasing its poultry to China, and the Select Subcommittee would state in its final report on the meatpacking industry in May that “these fears were baseless.”

*

Magaly Licolli, who can command with a look, is fazed neither by Tyson’s billions nor by the politicians, organizations, buildings, and roads it owns. “There is no need to kill workers in order for [Tyson] to have profits,” she said. She moves like water through rocks, constantly recalculating her tactics to keep pressure on the company. In Mexico she worked as an actress and was involved in theater as a tool for social justice. After she graduated from the University of Arkansas in 2013 with a degree in theater, she took a job at a community clinic in Springdale to help immigrants who couldn’t return to work at processing plants after being injured on the job.

Licolli met a Mexican woman at the clinic who had immigrated from Guerrero and been injured in the same chemical accident that had harmed Arrue. Her lungs were so damaged that she still has trouble breathing, making it difficult to complete small tasks like washing the dishes. (She asked to remain anonymous out of fear that she would not receive disability compensation, for which she is still fighting the company.) In 2019 the two women and sixteen others who had worked for various poultry companies in Arkansas founded Venceremos, a worker-based organization whose mission is to ensure the human rights of poultry workers. The group belongs to the Food Chain Workers Alliance, along with over thirty other organizations that represent some 375,000 food processing and agricultural workers in the US and Canada.

Venceremos means “we will win” in Spanish. The slogan has a long history of use by social justice movements in Latin America, first in 1960 by Fidel Castro in a speech demanding justice for the hundred workers and soldiers who died in the explosion of the French munitions freighter La Coubre in Havana harbor. “Venceremos,” written by Claudio Iturra, was the 1970 campaign anthem of Salvador Allende in Chile, a call to arms for workers, peasants, soldiers, and miners: “We shall prevail, we shall prevail/we know how to overcome misery.” For Licolli, it’s a fitting name for an organization led by women, who she says are at the forefront of changing the meatpacking industry. When I met with Licolli at the newly opened Venceremos center in Springdale in October, she stressed the importance of using art and theater to help workers organize. In 2020 workers with Venceremos made larger-than-life papier-mâché puppets for a protest to demand that Tyson close plants to allow workers to quarantine.

Licolli organized workers at different plants over the phone during the first months to get signatures on a petition demanding that poultry processing companies provide basic protective equipment, enforce social distancing, and share the results of Covid testing. That December, workers at a George’s plant in Springdale walked out to protest the company’s decision to end staggered shifts, which meant that more workers were entering the plant at the same time and that social distancing was practically impossible. “I had to bring attorneys to speak with the workers about certain activities,” she told me. “Many workers were afraid because it was their first time doing it.” In the aftermath of the protest, none of the workers were fired. “That,” she said, “was a huge victory.”

There are numerous challenges to organizing agricultural workers, many of whom are undocumented, illiterate or non-English speaking, unaware of their legal rights, and often have few economic resources. Organizers face the difficult task of earning the trust of workers who may be at risk of deportation and separation from their family in addition to being fired. In Arkansas many poultry workers are afraid to take part in any form of organizing that could endanger their jobs. But Licolli has organized Spanish-speaking workers by being committed, courageous, and present for them through the difficult pandemic years; she says that the fear of Covid has made many workers more receptive. “Organizing is really hard, slow work. It doesn’t happen overnight,” Marielena Hincapié, who recently retired after serving as the executive director of the National Immigration Law Center for thirteen years, told me. “It is about relationship building. It’s about trust building. And it’s most importantly about helping workers see and imagine a different reality.”

*

This past March, I joined Daniela, José, and four other Tyson workers on a pilgrimage from Arkansas to Florida. Licolli was bringing them to Immokalee to meet with representatives of the powerful Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW) and join a mass demonstration of food and agriculture workers in Palm Beach. It was the second time Licolli had brought poultry workers from Arkansas to Immokalee. When she organized the first trip with a group of four poultry workers in 2018, Licolli believed that the CIW model could change the poultry industry in Arkansas. During that trip, the CIW trained workers to teach other workers in the fields about their labor rights. The worker-to-worker educational model is an important tool for organizers in industries like agriculture and poultry: workers need to be offered classes in their native language—often at the place they work, since that is where they spend most of their time—and with visual forms of learning, since some are illiterate. “It’s more like, let’s have fun and learn together,” Licolli told me, “That is the power of popular education.”

As the plane took off, a tornado touched down in Springdale. While the adults worried about the path of the tornado, their children chatted about the ocean. They had never seen it before. When we arrived in Fort Meyers we hopped into rented cars and drove to the beach. José and his wife watched their four children run into the surf. It had been his wife, an immigrant from El Salvador who has been at Tyson for two decades, who first brought him to a Venceremos meeting in 2019 after she was invited by a coworker.

The couple weren’t sure what to expect in Immokalee and were nervous that their supervisors at Tyson would discover their participation. Fired workers have claimed they were blacklisted from getting other jobs in poultry processing or manufacturing in Arkansas. One of the other workers on the trip, Miguel, was the only person in a supervisory role at Tyson to have participated in Venceremos and asked that his real name not be used. “My whole life since I was a child I have been bullied,” he said, explaining why he had come. “It makes me upset to see people take advantage of other people.”

From the beach I rode with Licolli and the poultry workers to Immokalee, a town forty miles northwest of the Everglades. Most of the tomatoes Americans consume every winter are grown in the surrounding farmland. We arrived at the CIW community center, a sky-blue building that houses a Spanish-language radio station and sits across from a parking lot filled with school buses that transport agricultural workers to and from the tomato fields. Inside, there was a hum of frenetic activity.

The Coalition of Immokalee Workers has been organizing since 1993, and like Venceremos it began as a small group of workers meeting weekly. Over the years they developed a worker-led model for using protests and media campaigns to pressure retailers to source food ethically and encourage consumers to support just labor conditions. In 2011 the CIW launched the Fair Food Program, an agreement with the Florida Tomato Growers Exchange that supports workers by maintaining a third-party monitoring body to investigate labor violations. The program benefits some 35,000 laborers, primarily in Florida. Participating retailers pay a small premium to growers that is passed on to workers—an extra penny per pound of tomatoes that, if all major buyers were to participate, would nearly double farmworkers’ wages.

Under public pressure orchestrated by the CIW, McDonald’s, Burger King, Subway, and other large brands all joined the Fair Food Program, and it has since been expanded to Georgia, South Carolina, Virginia, Maryland, and New Jersey. The program has not only resulted in higher wages for tomato workers but also put in place a system for reporting abuse and sexual harassment on the job, measures to prevent wage theft, and education classes for workers to inform them of their rights. Of the five largest fast food corporations in the US, Wendy’s is the only one that has refused to join the program, claiming that all its tomatoes are sourced from greenhouses. Although Wendy’s has argued that greenhouse work conditions are safe and fair to workers, investigations have revealed that workers in them often have few protections. In 2016 the CIW launched a national boycott of the chain. Now the group was organizing a march in Palm Beach, home to the chair of the Wendy’s board, billionaire and Trump supporter Nelson Peltz.

Thelma Gómez, a community organizer with Migrant Justice with bright red hair, had traveled from Vermont with her twin eight-year-old daughters and a group of dairy workers to learn from the CIW. She began working as a teen at small dairy farms, in what she described as slave conditions: fourteen-hour days that started at 4 AM. She was underpaid and constantly sexually harassed. Gómez, who was initially undocumented, said that “nobody wanted to complain to the boss…because sometimes the bosses would turn workers in” to be deported. She got involved in organizing after she became a mother. “I want my daughters to be strong, and I want them to see us march together.”

At the CIW, workers demonstrated their collective power by picking up a truck in the parking lot and carrying it for several feet. As they sat together eating tamales in the Florida heat, several poultry workers compared scars from carpal tunnel surgery. José told me that no matter the injury, even if a person tested positive for Covid, they would be sent back to the line. “It doesn’t matter if the person has a sprained foot, a broken, crushed finger,” he said. “They have us all here as if we were machines. They don’t see us as people.”

Daniela found out she had breast cancer in early 2019. Her doctor gave her a note that allowed her to go to the bathroom at work whenever she needed. Even then, she told me, her supervisor would follow her to the stall and ask her loudly, as she emerged, why she had taken so long. In Immokalee, she rested in a rocking chair and rubbed her neck, which she had injured at work. “The body has a memory,” she told me, and looked at her hands. On one finger she wore a gold ring with a fuchsia stone. If you got close you could read, engraved in capital letters below the stone, TYSON. The ring, a gift from the company, had belonged to her husband. Her hands always hurt, pulsing as if they had been hit. She could no longer lift or open things—her fingers didn’t work as she wished. Yet in her sleep, she processed birds with such a ferocity that she would wake up covered in scratches and cuts. Her doctor gave her a cast-like glove to wear at night.

“I’m interested in everything here. They are very united and prepared,” she said, looking out over the parking lot of school buses. “There are ways to move forward when everyone works together.”

*

After breakfast on Saturday, April 2, the workers, their children, and local activists put on matching yellow JUSTICE FOR FARMWORKERS shirts and filed onto buses for the hour and a half ride to Palm Beach. José’s youngest child, three years old, wore a T-shirt that fit him like a dress, dragging on the ground as he walked with a Spider-Man toy in his hands. In the early morning light we drove past fields filled with workers.

Several hundred people arrived at manicured Bradley Park for the march, in a neighborhood of landscaped mansions two miles from Mar-a-Lago. Florida agricultural workers, joined by poultry, dairy, and construction workers, held tomato-shaped signs that read FIGHTING FOR FAIR FOOD and RESPECT JUSTICE. They laughed, hugged, sang, and played music. About half an hour before the march, the CIW set up a stage in the park and presented a play to educate bystanders about labor rights issues for tomato pickers. Lucas Benítez, the cofounder of the CIW and a former farmworker, narrated the play in Spanish with simultaneous English translation. The gathering crowd witnessed tomato pickers handling cardboard vegetables working under the protections of the Fair Food Program, while beside them workers who weren’t in the program suffered indignities, including sexual harassment. The role of Peltz was played by Gerardo Reyes Chávez, who was born in Zacatecas, Mexico, and began working in fields at the age of eleven. He helped launch the Fair Food Program, and CIW members refer to him as el flaco. Wearing a white wig, he loomed over a worker dressed up as the red-haired Wendy’s mascot.

Reyes Chávez told me that Palm Beach had laws to prevent protests, and the CIW had to sue the city in 2016 to gain the right to assemble. The workers marched through the streets and stopped at a high-end restaurant next to Peltz’s office. Palm Beach residents sitting in the street’s cafés and restaurants were confronted, if only for a moment, with the immigrant workers who provided their food. “I think it was very powerful to disturb their comfort,” said Licolli.

“I haven’t been able to sleep,” Miguel told me. “I’ve been thinking about what I will do when I return. Magaly was telling me that we could create a play about poultry workers.” Now that Venceremos has opened its center in Springdale workers have regular meetings there, though they’re difficult for those with families to schedule around shifts. Some Catholic workers have presented their Tyson supervisor a letter from their priest to receive an exemption from working on Sundays.

Upon returning to Arkansas, José was fired. His supervisor told him that he had done his job wrong, but refused to produce video footage of his work area to prove it. José now works at a cookie factory but still attends Venceremos meetings and keeps in touch with Tyson workers to document conditions at the plants. “I learned that only united can we achieve things,” he told me. “As workers we have many rights that we don’t know.” When I visited him in October he sat in a folding chair in his garage and showed me how he had deboned chickens during his time at the plant. As he spoke, his hands moved with precision through the air, one holding an imaginary knife. He said that at night he still dreamed that he was deboning chickens.

“I felt supported and sure of my rights as a worker,” Daniela told me when I visited her in July. She stood in her garage sifting through secondhand clothing and toys that she would send to Guatemala to resell. “I have learned to fight to live and survive. I’m not afraid.”