It’s hard to imagine two women more antithetical than the visionary singer-songwriter-poet Patti Smith, winner of the National Book Award for her memoir Just Kids (2010), and the Seagram’s liquor heiress Phyllis Bronfman Lambert, a trained architect and the founder of Montreal’s Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA), the world’s foremost museum of the building art. The rangy, androgynous Smith, seventy-six, has been revered by successive generations of hipsters as the ultimate punk rock goddess. The tiny, precise, owl-like Lambert, ninety-six, is known primarily to elderly architecture aficionados. Despite Lambert and Smith’s striking disparities, each has lately brought out a small-scale book of personal photographs, remarkably similar in their conception and palm-of-the-hand dimensions.

Smith’s heartfelt songs of innocence and experience speak directly to both the young and her contemporaries. This now-baritone troubadour’s cross-generational allure was on full display during her unforgettable rendition of Bob Dylan’s Sixties anthem “Chimes of Freedom” at Joan Didion’s memorial service last September at New York’s Cathedral of St. John the Divine, with which Smith closed the proceedings and brought down the house.

Making A Book of Days was Smith’s preoccupation during the caesura imposed by the pandemic. Its 366 images, one for each day of the year (plus an extra for leap year), are in some cases drawn from her daily postings on @thisispattismith, the Instagram account she launched five years ago to be “part of society,” prompted by Jesse Paris Smith, her daughter with the late rock guitarist Fred “Sonic” Smith. With a single photo per page, this gemlike design by Debbie Glasserman reveals the polymathic Patti to be wonderfully adept in yet another medium. Smith is also an astute borrower of other photographers’ works, which are interspersed throughout and provide rich counterpoints to her unpretentious directness. Carl Van Vechten’s luminous 1939 portrait of Richard Wright appears above the writer’s haiku about autumn on the page for the fall equinox. Elsewhere we find the rock photojournalist Allan Tannenbaum’s keyed up 1974 snap of Smith with Tom Verlaine, the punk rock musician with whom she was then romantically involved and whose death this January at age seventy-three she lamented in a touching New Yorker obituary.

Her own images range from domestic scenes like her jumbled bedside bookcase, her linen coverlet–draped “thinking chair,” and her Abyssinian cat, Cairo, watching her pack for a trip, to wistful views of the graves of artists she reveres—Shelley, Rimbaud, Whitman, Joyce, Woolf, Camus, Krasner, Pollock, and Sontag among them. There are also many cups of black coffee, her elixir vitae, shot everywhere from Smith’s Rockaway Beach kitchen to Brasserie Lipp.

Lambert, for her part, is the last survivor of the postwar International Style design establishment and was closely associated with many of its leading practitioners, particularly Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Philip Johnson, and Charles Eames. Her status was secured through her crucial involvement in the construction of Mies’s Seagram Building (1954–1958) on Park Avenue, the greatest skyscraper of that era. She convinced her father, Samuel Bronfman—who as a child fled with his family from anti-Jewish pogroms in tsarist Bessarabia to Canada and built Seagram’s into what would become the world’s largest alcohol company—to underwrite this top-of-the-line scheme instead of some corporate schlock.

Ever since, Lambert (who retained the surname of her husband, Jean Lambert, a French Jewish economist, after their five-year marriage ended in 1954) has remained Ms. Mies. Woe betide anyone who encroaches on that turf—the subject of her monograph-memoir Building Seagram (2013)—without her benediction. I learned that lesson at a 2009 Guggenheim Museum dinner that jointly celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of its renowned Frank Lloyd Wright building and of the Four Seasons restaurant in the Seagram Building, where the fundraising event was held. The program was a three-way “conversation” among Lambert, Guggenheim director Richard Armstrong, and me. Every time I mentioned Mies or the Four Seasons she interrupted, contradicted, or otherwise shut me down, to the increasing merriment of the audience. I felt as though I’d been transported into some nightmare Nichols and May sketch.

Her new opus is burdened by an awkward mouthful of a title—Observation Is a Constant That Underlies All Approaches—though Lars Müller, the book’s Zürich-based publisher, has insisted he concurred with that choice. This compendium comprises 323 images she has taken since 1959; as in Smith’s volume, almost all of the pictures are reproduced one per page. (Lambert, a self-professed “Instagram junkie,” also has an account there: @plamb27.) It provides intriguing glimpses into Lambert’s long life of extraordinary privilege and strenuous purpose, with a heavy emphasis on her excursions to see architectural monuments, close-up details of those far-flung treasures, and meals shared with friends. She is clearly fascinated by tattoos, cemeteries, empty chairs, quaint doorways, decaying infrastructure, reflections on glass, slanting rays of light on walls, and pointillist effects on water, with numerous examples of each. There are no fewer than nine self-portraits, including the book’s penultimate illustration, made at a mirror by the forty-six-year-old subject, who here bears an uncanny resemblance to Maya Lin.

Advertisement

There are certain notable overlaps between the two publications. Smith provides more than fifty photos of herself, making Lambert seem a shrinking violet in comparison. Although both collections contain multiple views of graveyards, Smith has obviously been motivated by her private feelings about the artists she memorializes, as in the bass player Tony Shanahan’s mournful portrait of her at Sylvia Plath’s final resting place in West Yorkshire. In contrast, Lambert does not specify departed individuals, and her memento mori shots seem chosen as intriguing compositions, such as a snow-covered Sacred Heart of Jesus tombstone in a Montreal cemetery juxtaposed across a two-page spread with a pile-up of discarded grave-marker crosses in a Turkish burial ground. Smith’s approach is always first-person and immediate, Lambert’s often aestheticized and emotionally distanced. However, in a few instances Lambert indulges a cloying sentimentality reminiscent of “The Family of Man,” the blockbuster 1955 MoMA exhibition curated by Edward Steichen, as in her 1971 photo of two children hugging on a Chicago street next to a poster that reads, “We need each other.”

Even when there are thematic congruities—and how could there not be, given the hundreds of pictures in each book taken during roughly equivalent time spans—the two assemblages are entirely different in tone and affect. The disparities are further accentuated by the authors’ very different handling of captions. Smith’s literate and pithy inscriptions appear under each photograph and illuminate her reason for choosing it, whereas Lambert’s terse name, place, and date summaries are consigned to an appendix and must be located by number, adding to an impression of remoteness.

Apart from a few successes—like an amusing lineup of four Jim Dine floor sculptures, titled The Plant Becomes a Fan, in her Montreal loft, and a fresh 1988 shot at Egypt’s Pyramid of Djoser of the husband-and-wife team of Diane Lefaivre and Alexander Tzonis dressed in requisite architectural black—the overall quality of Lambert’s memory album is amateurish, especially surprising since she had tens of thousands of her own takes to select from. This might seem less ironic were Lambert not such a stickler for name-brand excellence in the architectural photography she has acquired for the CCA with such great diligence and at considerable expense. Historically she has had little patience for photographs that lack the blue-chip validation she craves. She was never a self-confident connoisseur akin to Sam Wagstaff, the pioneering photography curator and collector who cared not a fig about provenance or imprimatur but depended solely on his own impeccable eye, and discerned merit whether a work was anonymous or by an acknowledged master, a magazine clipping or a platinum print.

During the 1980s my wife, the architectural historian Rosemarie Haag Bletter, and Lambert were among the attendees at a colloquium held by Columbia University’s Temple Hoyne Buell Center for the Study of American Architecture that focused on two recent books: Richard Pare’s Photography and Architecture: 1839–1939 and Peter Bacon Hales’s Silver Cities: Photographing American Urbanization, 1839-1939. Hales’s publication, which today is regarded as a classic, argues convincingly that the workaday shots ordered by land speculators, real estate developers, and building contractors can be exceptionally useful in tracing the growth of the designed environment. The scholarly gathering quickly devolved into one of Lambert’s demolition derbies.

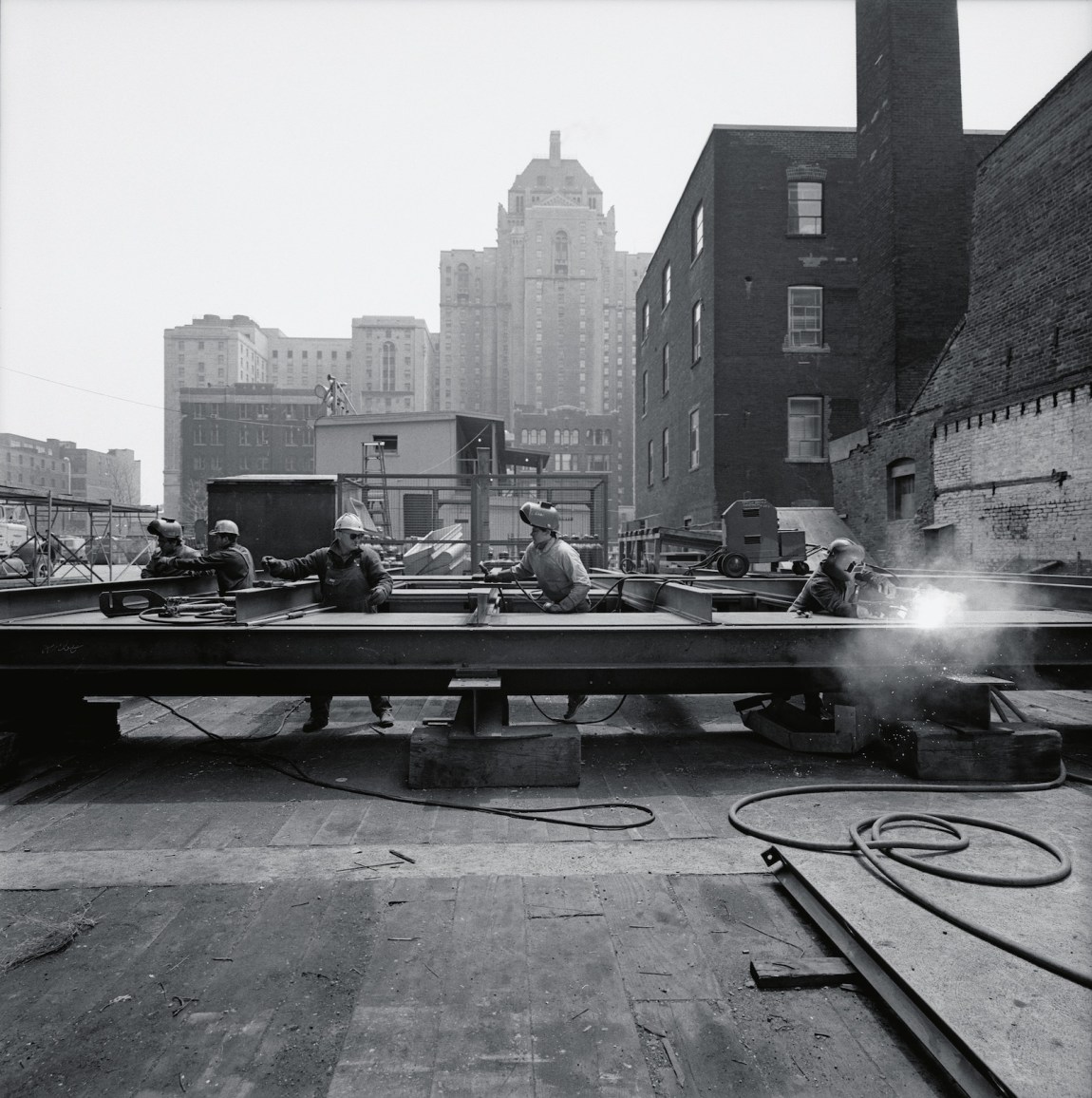

Like the rest of vintage photography at the time of the CCA’s founding in 1979, architectural photos were just beginning to be appreciated as fine art. This did not deter Lambert from ripping into Silver Cities because its unattributed images were not up to her exacting aesthetic standards, or maybe because it competed directly with Photography and Architecture, her fledgling institution’s first book. Pare, the distinguished British architectural photographer who at Lambert’s behest has undertaken a number of series documenting landmarks of modern architecture—most importantly the extant relics of Russian Constructivism, an assignment he began after the fall of the Soviet Union—was instrumental in assembling the CCA’s photography holdings. But that high-style preference should not negate the underappreciated importance of vernacular journeymen who captured evanescent moments in urban history.

Advertisement

The vehemence Lambert exhibited that day was typical of behavior that some close to her have likened to the volatile manner of the hard-driving, foul-mouthed “Mr. Sam” Bronfman. I touched on their familial tendency to bullying in a 1995 New York Times article occasioned by the completion of one of Lambert’s noblest endeavors—restoring the Ben Ezra Synagogue in Cairo, which some authorities think was founded before the advent of Islam in the seventh century. This heroic salvage operation began during the presidency of Anwar Sadat, an advocate of Arab rapprochement with Israel, and was funded by the Samuel Bronfman Foundation, with Lambert as head of the archaeological team.

She has not been strongly identified with Jewish causes like her two younger brothers: the late Edgar Bronfman Sr., who served as president of the World Jewish Congress for nearly a quarter-century, and Charles Bronfman, a cofounder of Taglit Birthright, a charitable organization that provides free ten-day trips to Israel for diaspora Jews between the ages of eighteen and twenty-six as a means of strengthening their religious identity (and, critics maintain, to build support for Israel when it is flagging among young Americans disturbed by the Netanyahu government’s mistreatment of Palestinians). However, true to form, Lambert does things her own way. As the Columbia architectural historian and former MoMA architecture curator Barry Bergdoll, a close friend of hers, puts it, she “does none of the observant things even as these matter a great deal to her brothers….I think there is a certain level of abstraction in deflecting that towards things like the restoration of the synagogue in old Cairo.” In other words, architecture she can handle.

Lambert now rarely makes New York appearances, so it was with much anticipation that on March 23 my wife and I headed to MoMA, where Lambert came to promote Observation Is a Constant That Underlies All Approaches. Her interlocutors were two no less formidable women of architecture: Elizabeth Diller, a partner in the New York firm Diller Scofidio + Renfro (famed for the High Line and MoMA’s latest expansion), and Sylvia Lavin, a Princeton professor of architectural history whose late father, the Princeton art historian Irving Lavin, shows up in Lambert’s new book, looking very jolly in a 2013 snapshot she took while a guest at the family’s Jersey shore house in Cape May Point.

We wondered whether advanced age had mellowed the doyenne of Miesianism, and she was in a benign mood as she fielded her interviewers’ questions, which veered between the featherweight and the fawning. Perhaps Diller was wary of pressing her too hard, considering Lambert’s riposte when Diller offered her a warm drink after a difficult journey to DS+R’s New York office, as she relates in Teri Wehn-Damisch’s documentary Citizen Lambert (2007): “I don’t want your fucking tea!”

Sporadically Lambert did let loose with a zinger, as when she called the Seagram Building’s current owner, the real estate developer Aby Rosen, “that crude man with no sense of curatorship,” a reference to the garish contemporary art with which he has adorned her beloved landmark and its plaza. “In New York it’s all money, money, money, money,” she continued, as though that has not been the city’s ethos since its founding.

Given the Bronfman family’s munificence in supporting manifold Jewish causes, a fitting Hebrew response to Lambert’s many admirable accomplishments might be dayenu, the Passover seder refrain that means “It would have been enough.” In her case it would have been enough had she only secured the Seagram commission for Mies, or established the CCA, or sponsored some of the finest architecture exhibitions of the past three decades, or preserved the archives of several modern master builders, or saved the Ben Ezra Synagogue. Observation Is a Constant That Underlies All Approaches confirms that it would have been enough to appreciate the many other achievements of this difficult character from afar, while A Book of Days makes you want to hang out with an old friend you’ve never met before.