Housewifery is hard work: taxing, by all accounts; isolating, by default; unwaged, by design. That is until 2006, when five women in Orange County were reportedly each given a few thousand dollars to be Housewives, Real Housewives, on cable television. They tottered, top-heavy, around Coto de Caza, their gated community, got Botox and went to Pilates, sent their daughters to prom and their sons to baseball practice. They gave Bravo viewers unmitigated access to their lives. And then, presumably, they filed Schedule Cs.

The Real Housewives franchise has since metastasized, expanding beyond the gates of Coto de Caza to include eleven cities and 154 women—some unmarried, some childless, many divorced. Their work is the production of drama, and they must be prolific to stay on the job. Conflict can emerge from petty slights of decorum (Can champagne be served in a red wine glass? Is it ever appropriate to tell someone she’s gotten a bad nose job?) or concerns more grievous (infidelity, alcoholism, tax fraud, Munchausen’s syndrome). The arbitration of these modern-day moralia will necessarily extend over multiple episodes—digested over lunches and dinners, settled in the belly for an episode or two, as loyalties shift and reconciliation seems nigh, only to reemerge like so much bile on one of the season’s many “girls’ trips” or multi-episode reunion specials.

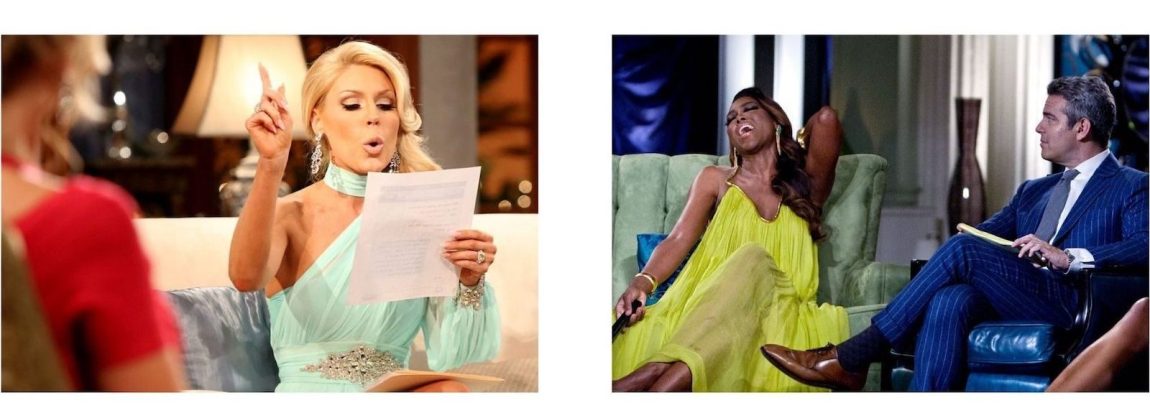

Reunions are hosted after a season has aired, giving Housewives the opportunity to assess their performances alongside their castmates (whose editorializing interviews have been spliced between the lunches and dinners) and their fans (who turn to social media to weigh in on disputes). In response, Housewives can defend their on-screen actions, sometimes supplying text messages, DMs, and other “receipts” to vindicate themselves. Or they can fall on their swords, take accountability for their bad behavior, and “own it”—as if their televised conduct were just another commodity for sale. Which, of course, it is.

It’s rumored that of the 154 women who have been hired as Real Housewives, only seven have ever quit. The rest are either currently filming, or they’ve been fired. This is a job they want—it’s a buyer’s market for Bravo. Andy Cohen, an executive producer of the franchise who is now also “the talent,” performing the on-screen role of the Housewives’ employer, has suggested that the women are motivated by celebrity—by the platform that Bravo affords them. “There’s one thing money can’t buy,” he’s said: “fame.” We might guess that they are also in it for the money. NeNe Leakes, longtime Real Housewife of Atlanta, reportedly earned $2.85 million dollars in her last season. It’s a lot of money for projecting an image of independent wealth.

Tamra Judge’s (alleged) $1.2 million per season, Teresa Giudice’s (alleged) $1.1 million per season, Lisa Vanderpump’s (alleged) $1 million per season—this is only their base pay. Housewives almost always use the show to promote or launch product lines: Ramona Singer’s pinot grigio, Karen Huger’s La’Dame perfume, Kandi Burruss’s Bedroom lube, to say nothing of the book deals (thirteen New York Times bestsellers to date), Broadway performances, spin-offs, paid promotions, and meet-and-greets that Housewives can turn for a profit. They have their own podcasts and millions of Instagram and Twitter followers, trawling for off-the-clock drama. Having sold their labor to Bravo, the Real Housewives can harness other women’s spending power; once they make it into the Housewife economy, they can capitalize on the greater content-creator economy.

The pioneer of the Housewife economy was Bethenny Frankel, who, in 2008, debuted on Season 1 of The Real Housewives of New York City, selling low-calorie cupcakes in supermarkets. In Season 2 of the show, she launched Skinnygirl Margarita, a low-calorie liquor brand that she sold in 2011 for $100 million. (In his book The Housewives, Brian Moylan reports that there is now a “Bethenny Clause” in all Housewife contracts, stipulating that Bravo will receive 10 percent if any company launched on the show sells for more than $1 million.)1 Many critics of the franchise have been disgusted by the Housewives’ conspicuous consumption and decadent displays of wealth. They do consume and display; they genuflect to the American Dream. But when we watch the Housewives shop or take vacations, we are more likely watching them make money than spend it.

This shift in perspective doesn’t require much imagination: contract negotiations have increasingly surfaced in the shows and their many spinoffs as plot. Does Marlo deserve to be promoted from a “friend of” role (paid per scene) to a full-time Housewife (paid per episode)? Did Kandi get Phaedra fired? Did Denise violate her contract by refusing to film with her costars? These are labor disputes, and though the Housewives are discouraged from breaking the fourth wall—and will never disclose their salaries—the terms of their employment have nonetheless become fodder for their televised fights, sometimes charted through loose metonymies: who gets to sit closest to Andy during the filming of a reunion? Who stands in the center during promotional photo shoots? Who, in other words, is the most valuable Housewife, the highest paid?

Advertisement

We enjoy these proxy wars for compensation—dragging the fact of women’s employment through the debased rituals of high school drama. Or, sometimes, routing the power plays of high school drama through the language of women’s economic empowerment. That we enjoy these fights for the power of Bravo’s platform is not lost on the network’s executives. In 2021 they premiered Ultimate Girls Trip, ostensibly a filmed vacation featuring past and current Housewives from various cities, but in practice an arena for fired Housewives to demonstrate their televisual value, clamoring to get rehired on their respective shows. It was the year that the franchise took a turn through the subgenres of reality TV: when Homeland Security descended on a Utah strip mall to arrest Jen Shah for money laundering and wire fraud, some critics delighted that The Real Housewives of Salt Lake City had become true crime. With Ultimate Girls Trip, the franchise became a reality competition—Survivor with glam squads.

The second season of Ultimate Girls Trip, set in the Berkshires in the summer of 2022, was almost explicit about this cutthroat premise, featuring only so-called “ex-wives.” The reasons for each of their dismissals (or were they “divorces” from the network?) were the wellspring of the ex-wives’ conversations. Many wanted to litigate the terms of their firing: Had they gotten too drunk too often, too angry to be entertaining, too demanding to film? Some wouldn’t even concede that they had been fired—only put “on pause,” presumably a network euphemism, but also a sign (as if we needed one) that Bravo’s executives are just as messy as their stars. These were not clean breaks; producers have led on their ex-wives, holding out the promise of an “unpause”: a new contract and a second chance. It’s rumored that at least two Housewives succeeded in their Ultimate Girls Trip performance reviews, and will appear back in primetime as early as this June.

The show’s third season, which premiered in March, sent its cast to Thailand and returned to the original format, including both current and “paused” Housewives in its cast. The eight women—from Salt Lake City, Miami, Atlanta, New York, and Potomac—had all seen their costars’ original shows. Some even identified as each other’s “fangirls.” They are fans, and they are comparatists, ranking each city’s strengths and weaknesses, implicitly justifying their continued employment (if they have it) and lightly veiling their resentment (if they don’t). That we need to subscribe to Peacock, the streaming platform owned by Bravo’s parent company, NBC, in order to watch Ultimate Girls Trip is money we find worth paying to see these Housewives compete for their platforms, which is to say their pay, which is to say their careers.

*

The labor of the lower-case housewife is invisible—it’s not legible as work, which is capitalism’s and patriarchy’s alibi for denying the housewife entrance into the waged economy. Tending to house and home is her passion, her nature. In being a housewife, she is merely being herself. The labor of the reality TV star is also invisible—she is merely being herself, albeit in front of cameras. This was TV executives’ alibi for having her scab. Although PBS’s 1973 documentary series An American Family is widely considered the seed of reality television, the genre didn’t bud until the Writers Guild strikes of 1988 or blossom until the Guild’s strikes of 2007–2008. Without new scripted content, network executives poured resources into unscripted alternatives. Nonunionized TV personalities substituted for striking writers, crossing picket lines on the way to fifteen minutes of fame.

Viewers have always been suspicious of the genre’s purported reality. Surely the presence of a camera informs the behavior of those performing in front of its lens. Surely reality TV stars are tailoring their behavior to appeal to audiences and network executives. Or, put more crudely, aren’t they just bad actors? Isn’t their “real” drama just as manufactured, produced, or even rehearsed as it would be on any scripted series? What, after all, gives the Housewives the right to call themselves “real,” when they aren’t even really housewives to begin with? They not only work outside the home as TV stars and hawkers of high-class merch, many of them also held salaried jobs before entering the Housewife economy, selling insurance, practicing law, or, fittingly, acting in soap operas.

Advertisement

That the rise of reality TV dovetailed with that of social media in the mid-Aughts led some critics to rehearse now familiar tenets of postmodern theory in response to these trends and their disruption of common-sense epistemologies (reality and authenticity are distinct from performance; truth is distinct from untruth). Don’t the Real Housewives have just as much claim to reality as do real housewives? Aren’t we all engaged in a recursive performance of our own selfhood—a performance only made more legible, but no less compulsory, by the cameras, streaming platforms, social networks, and data banks documenting and archiving our unexceptional lives?

But Reality is Reality TV’s red herring. Those looking to celebrate or castigate the genre for its claims to—or departures from—the Real will find themselves trapped in the revolving doors of this discourse or blinded by the flares of its jargon. Realness was Gloria Steinem’s principal objection to the Real Housewives when she appeared on Watch What Happens Live, Cohen’s late-night talk show, in 2015, calling the franchise “a minstrel show for women.” Objecting to the Housewives’ appearances—“all dressed up and inflated and plastic-surgeried and false-bosomed”—as much as their infighting, she said, “I believe that these women, in and of themselves, are much more serious and interesting than they’re ever allowed to display on the show, and I would love to see them as they really look, as opposed to looking 100 percent artificial.”

When Roxane Gay appeared on Watch What Happens Live in 2019, she defended the Housewives and their many feminist fans against Steinem’s argument that, as summarized by Cohen, “The Real Housewives are just kind of the worst for women.” Gay said, “I just really disagree…. I think that The Real Housewives franchises allow women to be their truest selves. We see the mess, the amazing friendships, and everything in between.” Steinem and Gay are right: the Housewives are real and artificial, true and manufactured, reproducing themselves and their brand as their life’s work.

When pressed, Steinem conceded that she watches The Real Housewives, that she’s seen many episodes from many cities, and that she can’t look away. “It’s like watching a trainwreck,” she said twice. But we don’t all watch the show as rubberneckers. Instead, some of us find in the Housewives’ dance between authenticity and performance a punishing form of pleasure. They are working to look like they are not working—is there a better metaphor for femininity? Theirs is a form of interpersonal women’s work that exaggerates the fine line between the housewife and the hussy, etymologically linked words that constantly threaten to collapse in on each other, wagering a woman’s reputation in the process. Did Erika Girardi intentionally flash Dorit Kemsley’s husband when she sat down at a restaurant, or was she just going commando to avoid a visible panty line? Was it an act of deviance or decorum? Did Sonja Morgan plagiarize Bethenny when she trademarked the brand name “Tipsy Girl” for a line of prosecco that never saw stores? Was it a form of infringement or homage?

In moments like these, we watch the Housewives jockey to control their own storylines, wresting them from producers and other castmates, resisting or embracing the roles that women are supposed to perform on TV and elsewhere: the Girl Next Door, the Good Mother, the Good Businesswoman, the MILF, the Bitch. We know these parts, and we know how hard it can be to control them—to save face, to not lose ground—even as the terms by which women are judged are constantly slipping beneath our feet. You could say that the Real Housewives rehearse the tragedy of femininity as farce. But femininity has always been both. The Housewives’ conflicts are famously uninteresting, but their negotiation of these conflicts—routed through their spectacular circumstances and stamped through the silkscreens of ideology—is more than interesting. It’s ridiculous, and it’s cathartic. Because it’s our work too.

*

Marxist feminists account for the role of the housewife in the production of capital by describing the product of her labor as the laborer himself. She feeds him, clothes him, cleans his home, availing herself for his sexual and psychological release, priming him for the next working day. It might be said, in contrast, that the Real Housewife produces herself as a laborer, self-stylizing for the cameras and self-commodifying for ad revenue and her product lines’ distribution. But this is only partially true. She has help. The invisible agents co-producing her performance are likely to be gay men: glam squads, stylists, and the shows’ literal producers, who coordinate her schedule, coerce catty confessional interviews, and inflect her speech with mannerisms inherited from queer subcultures. “I’m a whimsical gay guy,” said Carlos King, the longtime Real Housewives of Atlanta producer who was responsible for NeNe Leakes, “and [NeNe] laughed at my mannerisms. And then she would mimic them on camera. My friends would call me being like, ‘Why does she talk like you? Why does she act like you?’ but I was her producer. She fed off me.”2

If the Real Housewife feeds off queer men, she is merely completing the circuit of the camp Ouroboros: drag queens consume pop images of the woebegone housewife (Joan Crawford’s Mildred Pierce, Lana Turner’s Madame X); the Real Housewife consumes pop images of the drag queen, self-fashioning in her already facsimiled image. (Taking one more turn on this circuit of referentiality, the queens of RuPaul’s Drag Race now often self-stylize as Bravo stars.) To say that the Real Housewives present a “minstrel show for women” or a platform for their “truest selves,” then, is to miss the convolutions of this pop-cultural digestive tract.

The tropes of drag culture were features of the franchise from the start: women aging in high definition, negotiating their value after their childbearing years, compensating for youth with ornament, competing for attention from an audience that is prone to look away. NeNe Leakes and her castmates on The Real Housewives of Atlanta imported a queer lexicon to complement those tropes—words and phrases that originated in New York City’s Black and brown ballroom scenes: “I may be an open book, but that does not mean I am easily read,” announced Real Housewife Shamari DeVoe in her Season 11 tagline. “Call me a bad server, because I always spill the tea,” said Shereé Whitfield a season earlier. It can be awkward to hear the white Housewives of Orange County and the white Cuban housewives of Miami incorporate these and other appropriated terms—throwing shade, turning iconic looks—into their on-screen interviews and reunion shows. But the terms are also just descriptive.

Shade, Reading, Tea: these are coded forms of injury; queer-coded and Black-coded, yes, but also bits of feminized insult comedy, turning the shame of aging, of preening, of being a woman into an alchemized performance of shamelessness. The epithets that the Housewives sling at one another in the spirit of shade must land as entertainment—“Jesus Jugs” (Orange County Season 7), “Prostitution Whore” (New Jersey Season 1), “Rolling Hills of Neck”(Potomac Season 7)—not only for the viewer but for the Housewives themselves. We watch as they turn the slings and arrows of internalized misogyny into catchphrases for T-shirts and mugs.

In his defense against Steinem’s criticism, Cohen described The Real Housewives as a series of shows that are, first and foremost, about female friendship. How perilous. He often reminds viewers that each franchise begins with a group of women who have some loose connection to one another that predates filming. Their husbands might be colleagues; they might live on the same block; they must run in the same circles. New additions to the cast must have—or contrive—some link to the group to gain entry. Each show in the franchise is created by a separate production company, with some exceptions (Atlanta and Potomac are both produced by Truly Original; Beverly Hills and Orange County by Evolution Media). But this constraint of the genre remains constant, and it might explain why Bravo has had such a difficult time, as Cohen has described it, racially integrating the casts. Their social segregation—red-lined, recalcitrant—is our social segregation.

Efforts to cast nonwhite Housewives in Beverly Hills, Dallas, and New York City have largely failed. It’s rumored that Dallas and New York were put on hiatus after tokenized Black and Mexican hires resulted in stilted dinner parties, racist micro- and macroaggressions, and, ultimately, bad ratings. For eight years, The Real Housewives of Atlanta was the only Black iteration of the franchise. It was also the highest rated—by far. In 2017 USA Today reported that 61 percent of Atlanta viewers were Black, an audience not always captured by Bravo’s programming. (Notable Atlanta viewers include Beyoncé and Michelle Obama.) Despite that success, casting efforts in Philadelphia’s and Houston’s Black communities never went forward because both cities were deemed “too Atlanta-y,” according to one executive.

The network has an apparently endless bandwidth for exploring the ethno-regional nuances of whiteness (WASPS and Jews in New York City, Italian Americans in New Jersey, Mormons in Salt Lake City), but it took until 2016 for Bravo to land a second Black cast in Potomac, Maryland, where the women are light-skinned and green-eyed, and where their lives in a DC suburb can’t have them confused with the “urban,” which is to say undeniably Black, women of Atlanta. Race and racism are perennial subjects of the Atlanta and Potomac franchises, where Housewives are caught between dueling imperatives: to produce drama and perform respectability. This dilemma is especially acute on Potomac, where colorism and the women’s collective conservatism leads to constant negotiations of the color line (is biracial Katie as Black as light-skinned Robin?) and a form of self-policing that never fails to traffic in misogynoir.

There is an anthropological pleasure in watching the Housewives in their distinctly regional expressions of feminine injury and excess, but this should not be confused with “ironic viewing.” Irony and sincerity, like reality and fiction, are just another Möbius band for the Bravo viewer to skate. Some Housewives enter the show as self-appointed anthropologists (Carole and Bethenny of New York, Heather of Orange County, Heather of Salt Lake City), presenting themselves as savvier than average, describing their castmates’ antics with detachment, if not disdain. They’re not long for this role. They can’t stay above the drama because to remain on the show they have to make it. What’s more, we don’t really need a surrogate to provide us with commentary about the Housewives, because commentary about the Housewives—all that tea and shade—is the show. This is a tricky feedback loop and often a steep learning curve for the franchise’s would-be anthropologists: as soon as you try to discuss the show “from the outside,” you find yourself, like one of the Heathers, just another insider.

*

“We are all housewives,” Silvia Federici announced in her 1974 Marxist-feminist manifesto “Wages Against Housework.” Many women—professional women, single women—she wrote, “are afraid of identifying even for a second with the housewife [because] they know that this is the most powerless position in society.” Despite our marital or career status, women are all housewives because our household labor can always be taken for granted. If we work outside the home, our advancement can be denied, our wages suppressed, with the knowledge (or the presupposition) that we have men at home, primary breadwinners, devaluing our labor in and out of it. Women in the waged economy, in other words, have never left the housewife economy.

Bravo has not only transformed the Housewife title into an honorific, it has also made the Housewife and housewife economies seem strangely fungible. When the sitcom star Kelsey Grammer wanted to divorce his wife Camille in 2010, he encouraged her to become a Real Housewife of Beverly Hills. As he explained to Oprah Winfrey two years later, the show was a “parting gift” that he “bequeathed” to her—an identity and income for her to pursue while he pursued a new life with his new girlfriend, twenty-four years his junior. In Season 3 of The Real Housewives of Salt Lake City, Justin Rose, husband of Housewife Whitney, lost his job because they had let Bravo into their bedroom during the previous season. (The scene in question—the creation of what the couple called “Love Art”—featured them in their underwear, covered in dark navy paint, rolling around on a canvas, producing an abstract expression of their exhibitionist love.) It was behavior deemed unbecoming of Justin’s employer, LifeVantage, a nutritional supplement company that is rumored to be running a multilevel marketing scheme. On an episode of Ultimate Girls Trip following Justin’s termination, Whitney explained to her castmates, “I blew our life up over that moment, and it impacted my family in a negative way.” “However,” she added, “already this year, I have made more than he did last year.” For Camille Grammer and Whitney Rose, the Housewife economy seems to promise an exit from the housewife economy.

During her appearance on Watch What Happens Live (evidently a rite of passage for our most high-profile feminists), Camille Paglia celebrated the Real Housewives for offering women a path to professionalism without requiring that they sacrifice their “archetypal sexual power.” The Real Housewife can be a career woman, apparently, without becoming a shrew. Prone to letting provocation dictate her politics, Paglia waxed ecstatic about “the fabulosity” of the Housewives and their world in which “men are marginalized, men are shriveled” by the light of their wives’ “electric energy”—by an energy that “used to be glorified by Hollywood in its heyday” but that feminism has presumably dimmed.

If Paglia’s paean to the Housewives seems hyperbolic and more than a little reactionary, it is also a fitting reminder that the Housewife economy is not as novel as it may seem. Entertainment industries—Hollywood and especially network television—have always extended women a path out of housework, a way to sell their electric energy for a wage. Lucille Ball—not Raquel Welch or Liz Taylor or whomever Paglia had in mind—may be the real archetype for the Real Housewives’ “fabulosity.” A bored wife desperate to work on TV, Lucy Ricardo was Ball’s invention—not just the product of her labor and talent, but also of her life as Desi Arnaz’s wife, which was well-documented and publicized by tabloids. Lucille (the housewife) and Lucy (the Housewife) depended on each other, with one’s off-screen drama corroborating the other’s on-screen persona.

The apparatus for publicity tours has evolved since the days of I Love Lucy—they now include TMZ, Instagram fan accounts, TikToks, and podcasts—but the mechanisms of celebrity, reinforced by on- and off-screen performances, remain the same. We saw the tabloid news of Camille Grammer’s divorce and Justin Rose’s firing before we watched these events play out on TV. This didn’t diminish our fascination; it enhanced it. How would the show represent these already-represented events? The housewife and Housewife economies, it seems, are not fungible but inextricable. Camille Grammer (the divorced, off-screen housewife) and Camille Grammer (the on-screen Bravo Housewife) are both essential to her brand. Bravo’s franchise doesn’t launch women out of an unwaged job—it allows them to use that job as a platform for another one.

In accounting for housewives’ unwaged labor, Federici, Mariarosa Dalla Costa, Selma James, and their peers in the Wages for Housework movement took the housewife out from beneath capital’s shroud. They anointed her a viable, visible worker—not to ennoble her labor or even to compensate her for it but to welcome her into the fight against exploitation. Does the Real Housewife feel exploited? First-time cast members reportedly make $60,000 per season. They have to pay for their own hair and makeup and the upkeep—and perhaps even enhancement—of their homes for filming. Cohen reportedly makes $10 million a year. These numbers are hard to find and impossible to fact-check because unmitigated access to the Housewives’ lives is, ultimately, mitigated by the nondisclosure agreements in their contracts. Those who question the genre’s transparency—its unwieldy relation to Reality—should start here. Bravo gives the Housewife a wage. Perhaps she should form a union.