“Is there a text in this class?” For those who studied literature in the 1980s, this phrase was less a question than a slogan—a stand-in for the philosophical debates about language that occupied literary studies in the days of what is now, somewhat dismissively, called “high theory.” (Too high, is often the implication.) It was first posed by a student of the literary theorist Stanley Fish, who bandied it as a kind of riddle in an essay by the same name. What the student wanted to know, Fish explained, was not whether the class had a textbook, but rather “In this class do we believe in poems and things, or is it just us?” Are texts closed, their meanings as secure as a textbook between two covers? Or open—determined only by the contexts in which they and their readers move?

Fish’s essay transformed his student’s question into a social and intellectual code. You got its possible second meaning only if you got the method and milieu in which the student, by way of Fish, had been trained: that of deconstruction and French poststructuralism, of Jacques Derrida and his American interpreters. The question now circulates, if it circulates, with a patina of quaintness, conjuring up a bygone tradition and interpretive community that may sound a bit “off” to the ear. When faced with “Is there a text in this class?” one may as well be hearing “What’s in a name?”—no longer grappling with the question (or text) at hand so much as registering knowledge of a cultural inheritance. Once riddle, then code, now lore: Remember when people spoke like that? Remember when everything was a “text”? Paintings were texts, advertisements were texts, songs were texts—all available to be “read” and thus deconstructed.

Films, surtout, were texts, and they were predisposed to this uptake by jargon. Since World War II, filmmakers and critics, especially those hailing from France, had been describing cinema as a language, the camera a pen, and the screen a blank page on which an auteur could inscribe narrative, meaning, and desire. In the 1960s a younger generation of thinkers, again mostly French, began a programmatic analysis of film’s language-like components, introducing semiotics, the study of signs and symbols, into their analyses of cinema and popular culture. Under the influence of Roland Barthes, Christian Metz, Jean-Louis Baudry, and Raymond Bellour, cinematic images became signifiers, whose signified content was freshly open for interrogation.

In this stutter-step from “film is a language” to “films are texts,” the study of cinema became a new threshold for the study of ideology. Editing, camera movement, and mise-en-scène were newly understood as devices for encoding meaning, usually in the service of prevailing norms and institutions. A “film-text,” as the critic and filmmaker Peter Wollen called it in 1976, was distinct from a “film-representation” (a transparent view onto the world) and a “film-object” (a heap of celluloid). It was “a project of meaning with horizons beyond itself,” a project for understanding how political and social structures (capitalism, empire, patriarchy) reproduce themselves as indisputable truths. Umberto Eco once called semiotics “the discipline studying everything which can be used in order to lie.” It is also, importantly, the discipline studying everything which can be used to make lies seem like common sense.

“I can see that radical semiotic theory doesn’t sound the slightest bit like common sense, but that’s not really the point,” says a Ph.D. candidate named Julian in Crystal Gazing (1982), one of six films that Wollen directed with his then-wife Laura Mulvey between 1974 and 1983. Julian is talking to his friend Neil, an unemployed illustrator. “The point is that the ruling class doesn’t just rule by practical politics. It rules by defining the language as well. Look at the Social Democratic Party. The signified of politics hasn’t changed at all, only the signifier.”

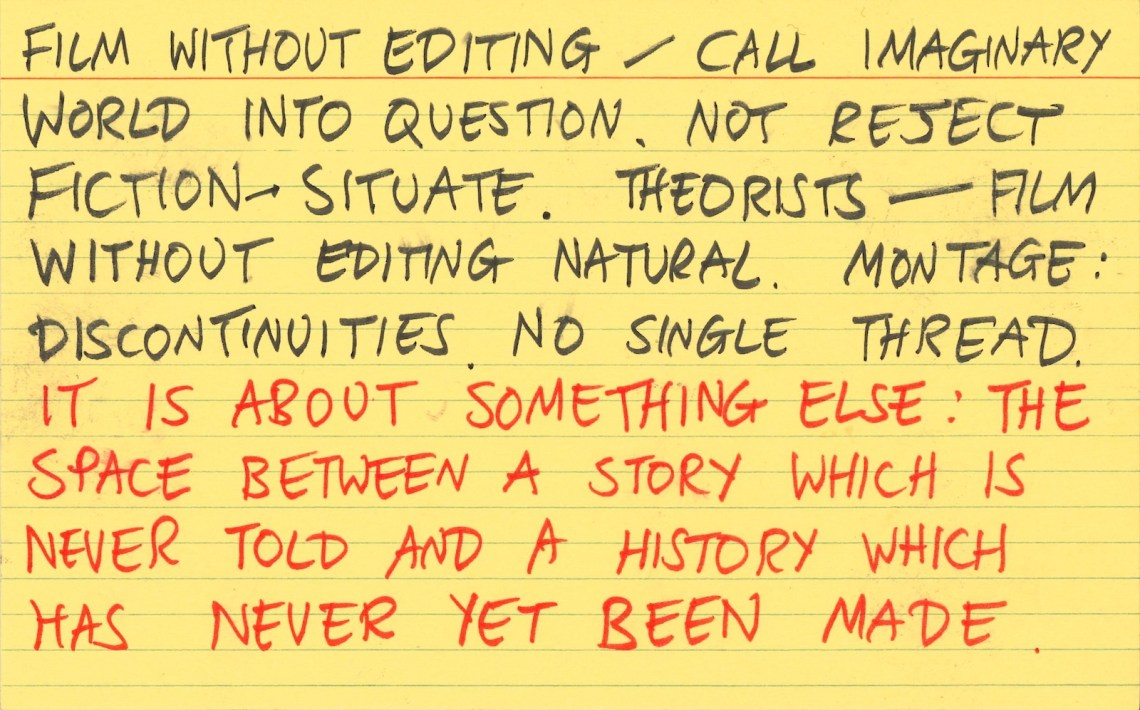

In Thatcher’s Britain, where a recession has hit miners and cultural workers alike, Julian’s words ring hollow. Neil isn’t moved; he’s cold. Why analyze signs when he can’t afford a new coat? But even as it trades in self-parody, Crystal Gazing doesn’t concede the point. This experimental film, full of narrative discontinuities and asynchronous sound, keeps demanding that the viewer scrutinize its own production of meaning—even and perhaps especially in an economy that devalues intellectual labor. No recession or retrenchment can stop signs from signifying. They will be read—the question is how?

*

Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen married in 1968, and although their writing about film is now highly anthologized, secured between two covers and too often cloistered within university libraries, their work didn’t originate in the classroom. They were grassroots intellectuals, fostered and sponsored by London’s feminist, Marxist, and independent film movements—the British Film Institute (BFI); the London Women’s Liberation Workshop, co-organized by Mulvey; and the New Left Review, where Wollen, who died in 2019, was on the editorial board. In 1974 the couple helped launch the Independent Filmmaker’s Association, which agitated for state funds for experimental filmmaking and, later, for the distribution of independent cinema on the newly envisioned public television station Channel Four.

Advertisement

“Peter’s and my shared love of Hollywood films had, from the earliest days of our relationship, been an integral part of our daily and our social lives,” Mulvey explains in the introduction to a new collection of their screenplays, edited by Oliver Fuke and published by the BFI.

But in the early 1970s our attitudes and commitment to the cinema changed. The Hollywood studio system was, by then, a thing of the past and we began to discover new avant-garde and feminist experimental films: cinema as critique, film as a radical aesthetic for a radical politics.

The relationship between cinema, critique, radical aesthetics, and radical politics—here represented by the loose conjunction “as”—was strengthened by film semiotics, which promised not only a way to understand mainstream ideology’s aesthetic principles but also a path toward their radicalization.

Mulvey and Wollen expanded the horizons of film semiotics from France to England, where their writing in Screen and Framework established both journals as forums of film theory with international reach. Their essays from the 1970s and 1980s, which drew on Lacanian psychoanalysis, Brechtian Marxist aesthetics, and Peircean semiotics, earned them the title of “jargonauts” in the London Review of Books—their theory traveling a little too far, perhaps a little too high, for Anglophone tastes. But such complexity of analysis was only fitting for what Wollen called “the most semiologically complex of all media” in his first, singular work of film theory, Signs and Meaning in the Cinema (1969).

Cinema presents the viewer with a kitchen sink of signification. It mobilizes images (moving and still), sounds (integrated or overlaid), writing, and editing—to say nothing of the psychological mechanisms of projection, fetishism, and scopophilia. If a morphological analysis of North by Northwest or an examination of the castration anxiety that haunts Rear Window threatens to drain these films of their Technicolor pleasure, that was, Mulvey argued, explicitly the point of the couple’s theory and practice. Beyond film studies—where she continues to write on the history and theory of film, video, and digital art—Mulvey is most famous for her 1975 essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” in which she announced at the start her intention to “analyze pleasure” and in so doing “destroy it.”

Still a staple on Introduction to Cinema syllabi, the essay defines the “male gaze”—a term she coined—as the repertoire of psychic and formal techniques by which Hollywood’s men are coded as active spectators, while women are made passive recipients of the camera’s look. Whether heroine or femme fatale, she is the “bearer…not maker of meaning.” The result of her analysis, Mulvey wrote, was not to produce “a reconstituted new pleasure” or an “intellectualized unpleasure, but to make way for a total negation of the ease and plentitude of the narrative fiction film.” Having pried open the codes of conventional filmmaking from aerial heights, the jargonauts never let their feet leave the ground. Instead, they cleared it, making room for a new cinema—a counter-cinema—to emerge.

*

In 1974, while Wollen was a visiting professor at Northwestern University, the couple made their first film, Penthesilea, using equipment from the university’s film program and $5,000 of his salary. It’s a heuristic film, tentative with answers but unflinchingly bold in the questions it asks: not just how women have been inscribed in the Western imagination but, more pressingly, how they might represent themselves otherwise. What mediums, what codes, can they adopt? Is it possible to protest from within the very languages that have been developed to silence them?

Penthesilea broaches these questions by examining representations of the mythical Amazon queen killed by Achilles during the Trojan War. Cinematically, Mulvey later wrote, the film took a “scorched earth policy,” a “return to zero,” but like her 1975 essay, it approaches ground zero analytically. Each of its five sections presents the myth of the Amazons from a new perspective and a new medium:

1. Theater. A troupe of mimes stage the drama of Penthesilea as interpreted by Heinrich von Kleist’s play of that name, which reverses the murder of the original myth: here the Amazon queen kills Achilles and then herself.

2. Verbal language. Wollen gives a lecture on Kleist’s play and its departures from classical mythology: “For both the ancient Greeks and for Kleist,” he says, “the image of the Amazon was both fascinating and frightening. It still has the same power today.”

3. Plastic arts. A slideshow projects depictions of Amazons in the history of Western visual culture: a Hellenistic frieze in marble, a painted panel by Rubens, a 1972 Wonder Woman comic.

4. Cinema. Footage of an actress speaking the words of the American suffragist Jessie Ashley is superimposed over a women’s suffrage propaganda film from 1913. “Is it impossible for all women to work together to uproot an injustice common to all? Is there no way to bring this about? Surely there should be,” she says, ultimately conceding the limits of her oration: “Voluntarily, I hold my peace.”

5. Video. Four TV monitors display the four preceding sections. The camera zooms in on each monitor, alternating between their reproduced sounds and images.

The drama of Penthesilea—a symptom of male fears and fantasies—repeats itself across the film, across art forms, and throughout history. But as each section gives way to the next, the Amazon queen becomes less a coherent myth than a figure of instability and contradiction, a screen onto which artists have projected untold secrets of the unconscious. She becomes, in other words, a text to be read.

Advertisement

In the final scene the mime who played Penthesilea in the first section sits at a mirror, removes her makeup, and struggles, through Wollen’s off-screen coaching, to pronounce her last lines:

Women looked at each other through the eyes of men. Women spoke to each other through the words of men. An alien look. An alien language. We can speak with our own words. We can look with our own eyes. And we can fight with our own weapons.

But what are women’s words, women’s eyes, women’s weapons? How can we speak, see, and fight without picking up the master’s tools? Who, for that matter, are we? What constitutes the category “women” beyond our collective subordination under patriarchy? These were questions that preoccupied the feminists in Mulvey’s reading groups and workshops—the psychoanalyst Juliet Mitchell and artist Mary Kelly among them—who marshalled theory, film, photography, and performance to venture answers. They remain open questions today.

Across their first three films, Mulvey and Wollen returned to the riddle of sexual difference—a riddle coded as ideology and transmitted as lore, made natural and therefore unquestionable despite the persistent openness of its query. Their next two films, Riddles of the Sphinx (1977) and AMY! (1980), approach the myth of Oedipus by way of the Sphinx and the myth of “the heroine” by way of Amy Johnson, the first woman to fly solo from Great Britain to Australia. Both films use many of the same techniques as Penthesilea, introducing halting discontinuities between sound and image, juxtaposing multiple worlds and multiple voices, wrenching signifier from signified. But each also introduces narrative elements.

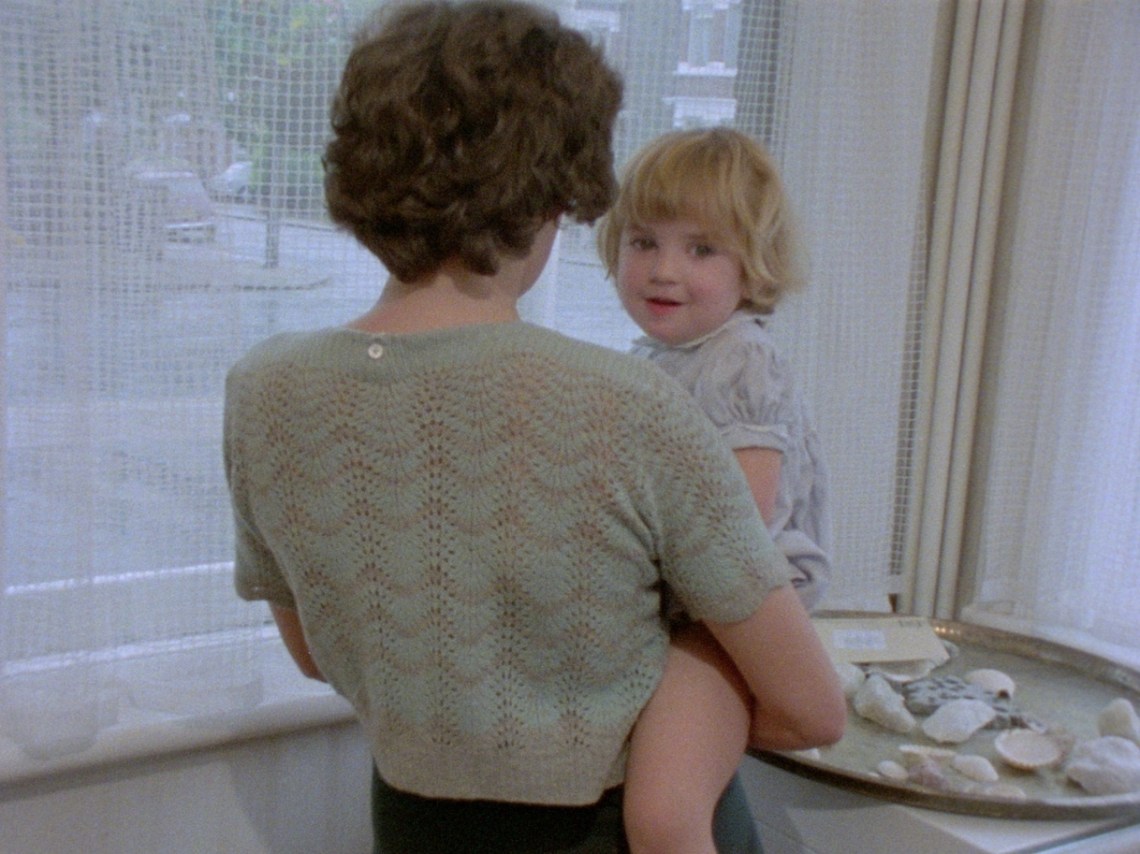

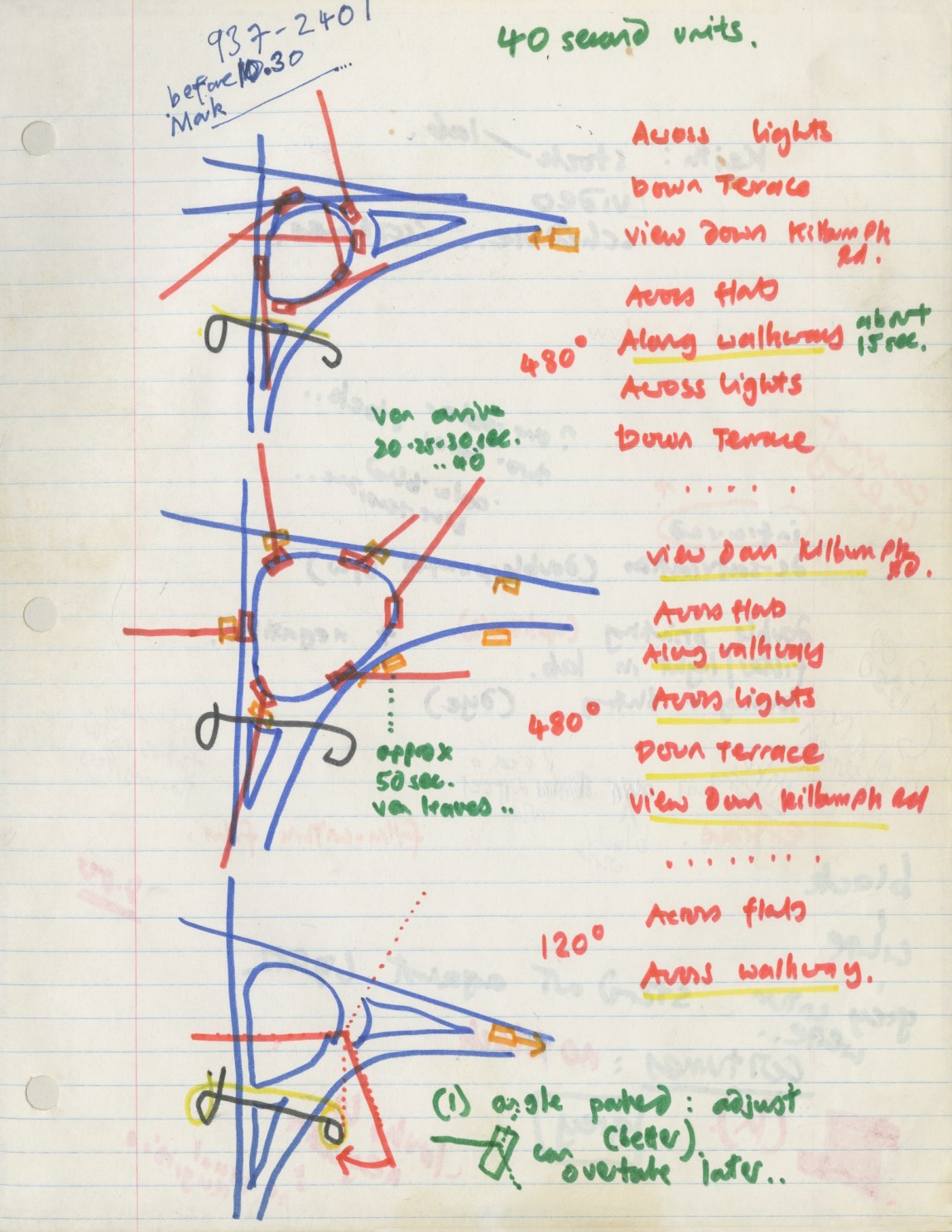

The most famous tableau in Mulvey and Wollen’s films is the central and longest narrative section of Riddles of the Sphinx. A young mother named Louise separates from her husband, gets a job as a telephone operator, organizes for childcare at work, rejects the nuclear family unit, and begins coparenting with a close female friend. The narrative is divided into thirteen shots, all from a single camera mounted on a tripod that rotates in a slow 360-degree pan. We only glimpse Louise, her child, and her coworkers momentarily and haphazardly, as their movements intersect with those of the camera. This is not cinema ground zero, but an experimentally constructive cinema, imagining what women’s words, eyes, and weapons might be outside of patriarchy. It doesn’t spare women the tight grip of objectification by simply inverting the male gaze into a “female” one. Instead the camera moves to “elide the possibility of a fetishism of the female body,” in the scholar Mary Ann Doane’s words, short-circuiting what Mulvey called “the looker/looked-at dichotomy” altogether.

*

Uneasy and estranging, these films are hard to watch. But they are even harder to see. Riddles of the Sphinx is available from the BFI on home video and their streaming platform, and The Bad Sister—the couple’s last collaboration—is available on the Roku Channel, but the rest of their work remains absent from general circulation. Pirated copies of Crystal Gazing and Frida Kahlo & Tina Modotti (1983), about the artists’ crisscrossing histories in the aftermath of the Mexican Revolution, were sent to me as digital files. Friends or friends-of-friends attached them to e-mails with the caveat Do Not Circulate. This is counter-cinema as contraband. The Bad Sister, featuring a sibling rivalry that is perhaps also a metaphor for the split subject, is the least known and least seen of Mulvey and Wollen’s films, despite its mass circulation on Channel 4 in 1983. It aired there only once.

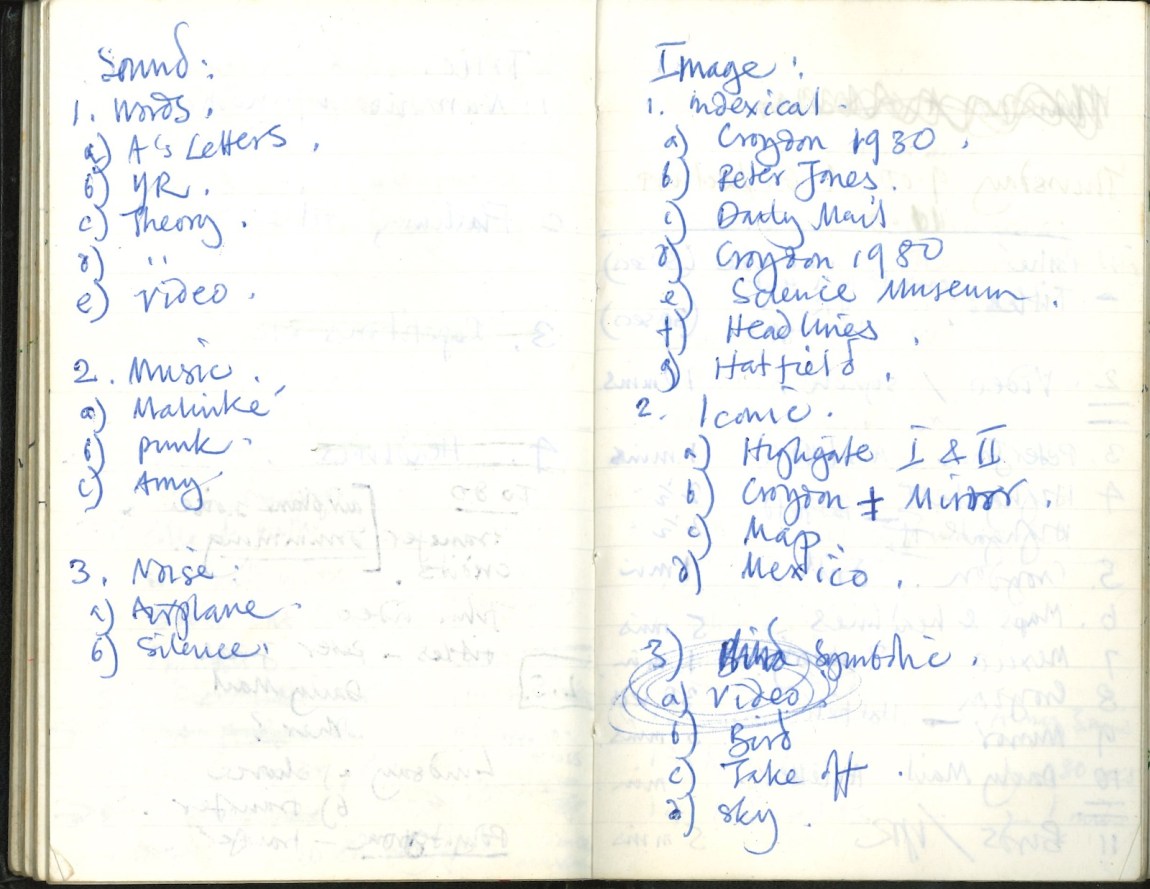

Fuke’s new book for the BFI, The Films of Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen, can only do so much to remedy the films’ inaccessibility. It collects scripts from the couple’s six collaborations and from the films they made independently—Wollen’s Friendship’s Death (1987), Mulvey’s Disgraced Monuments (1994) and 23rd August 2008 (2013)—as well as two scenarios for unmade collaborations.1 It also reproduces handwritten working documents from the films—Wollen’s lecture notes from Penthesilea, a diagram of the panning camera in Riddles, a shot breakdown that clarifies Crystal Gazing’s three-part schema—and compiles nine new interpretative essays by film scholars across generations, including Mulvey herself.

There is something strange about seeing these polyvocal, image-dense films on the printed page. It’s a strangeness that returns us to Stanley Fish’s riddle: Is there, we might ask, a film-text in this text? Dialogue can be transcribed and intertitles reproduced (with useful footnotes to the many quotations that Mulvey and Wollen used, pastiche-like, throughout their work), but how to translate a montage of images? “Reading a screenplay is usually a barren and arid experience, intellectually as well as emotionally,” Wollen wrote in Signs and Meaning in the Cinema. Yet he and Mulvey still published screenplays of Riddles of The Sphinx and AMY! in Screen and Framework after those films premiered. What we see on the page—in these journals and in the new BFI collection—are not “film-texts” so much as companion texts.

As companions, they’re worth having. The new essays are particularly useful guides through films that demand the viewer’s close attention to produce meaning. They make you long to see the films themselves, but like so much avant-garde cinema from the “long 1970s”—a utopian moment for the medium, in which films by Chantal Akerman, Jackie Raynal, and Yvonne Rainer likewise projected a new horizon of feminist possibility—Mulvey and Wollen’s cinema seems to be stuck in clogged distribution channels. As a result, it risks becoming a fetish object relegated to the academy, which was never its proper home.

*

In the graveyard of lost jargon, there are certain words that refuse their interment. They haunt us now, reanimated by current events, with the promise that yet another Return to Marx or Freud and their scientific vocabularies might likewise reanimate the movements (labor, feminism) that once used these words as interpretive tools and political fuel. Other terms are not so lucky. Few, it seems, are especially eager to resurrect signifier and signified, nor to see the gap between them as the ground for political action.

“The male gaze” became a useful descriptor for an omnipresent cultural phenomenon. It fortified movements within Hollywood and independent filmmaking agitating for more women directors and more “active” film roles for women. It helped articulate an industry demand, not a readerly one. By contrast, Mulvey and Wollen’s way of thinking about text and textuality has always been an imposition on the reader. It now no longer benefits from the sparkle of theoretical novelty; nor is it backed by the tailwinds of May 1968, promising to feed a collective hunger for ideology critique.

But if their language sounds “off” to the contemporary ear, that might also be because it was never meant to sound “on.” In his 1972 epilogue to Signs and Meaning in the Cinema, Wollen wrote that “the text” was not “the transport system which conveys the finished product” but rather “the factory where thought is at work.” He warned of “the danger of the myths of clarity and transparency,” which “present thought as pre-packaged, available, given, from the point of view of the consumer.” This suspicious orientation to “clear” or “transparent” communication is especially challenging in the United States, where plainspokenness is next to godliness—and just as foundational to our electoral politics. American readers’ suspicion of jargon is the flipside of a European tradition that looks upon “transparency” with equal dismay. One reflex sees words pulled from theory as impediments to thought-consumption. The other sees them as enablers of thought-production. (No surprise that the American tradition values the experience of consumers over those of producers.)

Mulvey and Wollen aligned themselves firmly with the European position. In their films and theoretical writing, they promote a politics of reading, a politics founded on the premise that “thought is work.” In his lecture in the second section of Penthesilia, Wollen reminds us that “myths can never conclude anything; they can only die when the problems they express are superseded.” Our myths about gender, capital, and language are extraordinarily alive, promising to crush those who don’t conform to their contours with the full weight of American law. What is a woman? What is work? What is truth? These signifiers have always been radically unstable. If they seem more so now, that is only to say that our myths are changing, and that stabilizing their terms, restoring their order, is of urgent concern to those in power.

The gears of our political system are jammed, and we are squabbling over signs—over who gets to define what words, and who gets to anchor them in “commonsense” meaning. Instead of disputing whose worldview is correct, we might consider how worldviews are made and how they’ve been made to seem so rigid and closed. In this state of affairs, it may be time to return to the text.