In June 2019, shortly after directing the massacre of a sit-in outside the army’s headquarters in the Sudanese capital, Mohammed Hamdan Daglo “Hemetti”—the commander of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a mercenary army of over 100,000 men—warned that “Khartoum could become Kutum.” He was referring to a much fought-over little town in North Darfur that Le Monde reported was once “emptied of its inhabitants” by his militiamen. “People will abandon the high houses, only the cats will remain.”

Today Hemetti is fulfilling his threat. Since fighting broke out between Sudan’s army and the RSF in April, Khartoum, a city with a population of close to nine million in its metropolitan area, has been abandoned by well over a million people—including most of the wealthy bourgeois families of the old city, whose comfortable “high houses,” when not reduced to ashes, have been stormed by the tens of thousands of looting young adventurers Hemetti has recruited from the lumpenproletariat of Darfur and the rural areas of Chad, the Central African Republic, Niger, and Mali. Meanwhile, Khartoum’s supposed defender, General Abdul Fattah al-Burhan, rich in MiG planes but bereft of infantry, is holed up in a bunker in the heart of the city’s military zone, acquiring a milky pallor in the shade of its thick walls. Mocking women have derisively requested he share the secret for his skincare routine. Even amid this immense tragedy, the caustic humor of the Sudanese survives.

Khartoum is often thought to operate like a metropole with an imperial relationship toward regions in the south and west, and Hemetti likes to present himself as a hero of the margins rising up against this predatory and haughty center. But the war in Sudan is not really a civil war, in the sense of a conflict that pits segments of the nation against one another in the name of conflicting sociopolitical interests. Nor is it quite a tribal or ethnic war, although this dimension is not absent, as in Darfur, where nomadic Arab and Arabized tribes are in conflict with sedentary groups, both Arabs and those that are primarily seen, with derogatory connotations, as “Blacks.” We might compare it to the feuds of Italy’s quattrocento, when powerful families with private armies fought for monopolistic control of common riches, crushing in the process anyone who aspired to free, republican government. Hemetti’s family heads a clan that has amassed a multibillion-dollar fortune by seizing many of the country’s resources, in particular its gold. For its part, the organization that passes for Sudan’s army controls over two hundred companies across all sectors of the economy—gold as well as rubber, meat exports, flour, and sesame—and brings in more than $2 billion, untaxed, annually to a caste of potbellied generals and the Islamist power brokers who oversee them.

What we have here is an armed struggle among oligarchs over the spoils of a single, now-defunct regime of predatory accumulation: Omar al-Bashir’s Islamist government, which ruled Sudan from 1989 to 2019, when it imploded under both the weight of its own contradictions and the pressure of a revolutionary democratization movement. The outbreak of this war of the generals came as a shock even to Sudanese observers, as did the devastating scale of the conflict’s violence. To date it has caused almost two thousand deaths and displaced more than 2.5 million people in Darfur and the Khartoum region.

The surprise came from the fact that both domestic and international scholars and experts involved in Sudan’s affairs had convinced themselves that the country was in transition toward democracy and constitutional rule. That is what thousands of Sudanese activists had been fighting for, and representatives of Western countries saw it as the endpoint of the process. In theory, after the fall of al-Bashir, the two generals, al-Burhan and Hemetti, were to be mere extras in a democratic transition led by civilians: the country’s political parties and the civil society organizations united in the Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC) coalition. Various Arab powers, in particular Egypt and the United Arab Emirates, were meanwhile maneuvering to ensure that, under cover of democratic formalities, their own champions—al-Burhan for Egypt, Hemetti for the UAE—would retain power and influence. As a result of both this support and the immense wealth they controlled, the two generals acquired greater influence in the transition, al-Burhan as chair of the Transitional Sovereignty Council and Hemetti as its deputy chair. The idea was that, in exchange, they would not use violence to end the process. This implicit trade-off reassured most observers that the transition would be peaceful, if bumpy. But the concession was not enough.

The brutality of the current war might lead us to scrutinize the actions and motivations of Hemetti and al-Burhan, but in the longer, underlying struggle in Sudan, they both belong to the same camp: that of a “Sudan of the origins” fighting the emergence of a nation that does not yet exist, has never existed, but that has been the continuing aspiration of an activist, peaceful movement of Sudanese people since the years leading up to Sudan’s independence in 1956, most recently starting in 2018. In preparing this essay, I spoke to many Sudanese citizens and asked them whether they would like to see al-Burhan or Hemetti emerge victorious from the conflict. The unanimous answer was al-Burhan, but by no means out of support or sympathy for his cause: he is not the friend you hope to make but the enemy you’d rather have. To understand the point of view of Sudanese civilians (which is the point of view that must count, though it has weighed so little so far in the decision-making of the international community), we need to follow the trajectory of the repressed but resilient struggle for a democratic Sudan.

Advertisement

*

Predation is at the root of modern Sudanese history. Although the dubious honor of inaugurating colonialism in Africa is usually assigned to France, which seized the Regency of Algiers in 1830, it should really go to Muhammad Ali Pasha, who ruled Egypt in the early nineteenth century under the nominal tutelage of Ottoman Turkey. Starting in 1820 he methodically seized the Nilotic regions beyond Egypt’s southern borders. His primary aim was to build a reservoir of slaves, who were mainly to serve as his dedicated army. But soon, fascinated by the capitalist boom in Western Europe, he transformed his conquest into a plantation colony that would supply European industry with raw materials. The city of Khartoum was founded as the headquarters of this scheme.

The region’s earlier history, while not devoid of conflict, had been marked by relatively high levels of collaboration and intermingling among the diverse peoples and cultures who lived there. From the outset, Muhammad Ali’s project created an opposition between the center and the peripheries that was to mark the country’s subsequent history in a thousand often violent ways. Two peripheries in particular were to become important: Darfur, where nomadic Arab or Arabized tribes lived alongside sedentary Blacks and Arabs; and the southern region beyond the vast swamps of the Sudd, with its animist Black peoples.

Egyptian domination, known to the Sudanese as the Turkiyya, was cut short in the early 1880s when a jihadist leader who presented himself as the Mahdi—the messiah of the end times, according to Islam—took over the land and installed a theocracy that lasted nearly twenty years. After his early death, of typhus, in 1885, the Mahdi was succeeded by one of his caliphs, Abdallahi ibn Muhammad, a talented administrator and relentless warlord (he tried to invade Egypt and Ethiopia) who came from an Arab tribe in Darfur. Hemetti sometimes compares himself to ibn Muhammad.

Toward the end of the century the caliphate regime, or Mahdiyya, became a collateral victim of the colonial rivalry between Britain and France. Just as would happen five years later with the caliphate of Sokoto in northern Nigeria, in 1898 Britain rushed to conquer the Mahdiyya state in order to thwart the French colonial enterprise after a small Gallic expedition reached what is now southern Sudan. The entire region fell under the control of the British Empire, which did not change its structure of center and margins. The British could even be said to have reinforced that structure by opposing both the activity of Christian missionaries in the north and any process of Islamization in the south—where, on the other hand, missionaries were given carte blanche.

British colonization created a “useful Sudan” around export croplands in the fertile alluvial districts of the Nile south of Khartoum, which were linked by rail to Port Sudan on the Red Sea. In Khartoum, the British established educational institutions to provide auxiliary personnel for the administration of these riches. But they never established sturdy state structures, instead vacillating between different administrative experiments. To solve the problem their presence posed to international law, they set up a “condominium” regime, involving the country’s nominal master, Egypt, in their colonial management. This arrangement worked to the benefit of the British as long as Egypt itself remained under their tutelage, but by the 1930s Egypt had regained much of its sovereignty and began to push for its own vision of Sudan—first by demanding a say in managing the waters of the Nile, and ultimately by advocating Sudanese-Egyptian unity.

The entities that would constitute the political scene of independent Sudan emerged during the colonial period, particularly in the 1940s, when liberal reforms enabled a civil society to take shape. They included trade unions; organizations representing communities, minorities, and women; and political parties, some “traditional” and others “modern.” On the traditional side were the sectarian parties, established by two major Islamic confessional groups: former supporters of the Mahdi called the Ansars (“defenders of the faith”), and the Khatmiyya, an Islamic sect that had supported Egyptian colonialism. Both sects advocated a leadership drawn from the traditional and religious notabilities, but the parties they created stood for opposing causes. The Ansar, mobilized by the National Umma Party, represented a Sudanese nationalism that defined itself against Egypt, while the Khatmiyya and its Unity Party supported union or at least a structural partnership with Sudan’s northern neighbor.

Advertisement

On the modern side, graduates of British schools formed “secular” parties that were not necessarily purged of religion but, unlike the sectarian parties, did not affiliate with any religious movement. The most important was the Communist Party, whose social base was limited for the most part to railway workers, university students, and small groups of unionized urban laborers, but which exerted considerable ideological influence on civil society movements.

What all these forces had in common was a genuine or strategic attachment to democracy. The traditional or sectarian parties, who knew they could count on large reservoirs of votes, accepted democracy as an easy path to power, and the secular parties had no other raison d’être than parliamentary rule. Even the Communist Party, whose ultimate goal was socialist revolution, accepted democracy for practical reasons: in a country where Islam was the national culture, at least in the north, its reputation for irreligiousness, even atheism, meant that it had to rely on democratic politics if it hoped to gradually broaden its base.

*

In principle, once Sudan had gained independence in 1956 it should have been able to carry on within the Westminster system of parliamentary governance bequeathed to it by the British. But it got off to a bad start, with what seems to be the curse of some former British colonies: the threat of partition. In Sudan, much as in India and Nigeria, this threat arose when the colonial power exacerbated religious and cultural divisions between two blocs, neither strong enough for one to easily absorb the other. A civil war broke out just before independence when the north, where state power was concentrated, tried to impose a form of internal colonization on the south by means of Islamization and Arabization.

The crisis created the opportunity for a suspension of the democratic system. As the first Sudanese parliament was preparing to meet, General Ibrahim Abboud used the army to overthrow the elected government and establish a military regime. Sudan was in this sense an early experiment in the tribulations of the postcolonial state: the continent’s first independent sub-Saharan country also had its first military putsch and its first civil war. The important point is that, from the outset, the army appeared as the greatest danger to democracy. Even at this stage, some of Sudan’s best minds reckoned that the solution to the problems the country had inherited—its structure of center and periphery and its accompanying Arab-Islamic supremacism—lay in democracy. That was the view of the Communist leadership, which militated for autonomy for the south and backed the cause of minorities.

It was also the view of a leading religious-political thinker of the time, Ustaz Mahmoud Mohammed Taha, who developed a theology of democratic Islam. Among other things, he argued that the sharia law that Islamists and conservative Muslims claimed as the quintessence of the faith was based on verses revealed to the Prophet Mohammed in Medina, which constituted a wartime doctrine that was transitory and adapted to the realities of life in seventh-century Arabia. It was full of rules and threats that contrasted with the true and permanent message of the faith, what he called “the second message of Islam.” This, he said, was delivered in the Meccan verses and, as George Packer once summarized it for The New Yorker, “suffused with a spirit of freedom and equality,” including between men and women, Muslims and non-Muslims. True Islam was a religion of democracy and social justice, which Taha tried to promote in Sudan through the establishment, out of his political party the New Islamic Mission, of an activist network named the Republican Brotherhood (which also included Republican sisters), partly in rebuke to the Muslim Brotherhood.

The Sudanese branch of the Muslim Brotherhood grew in the late 1960s under the leadership of Hasan al-Turabi, a charismatic intellectual with an unlikely profile—he was a Sorbonne graduate and the son of a Sufi family. This development was still more dangerous for democracy than the army. In 1969 Colonel Jaafar Nimeiry led the army in a coup to depose President Ismail al-Azhari. Claiming to promote national development by placing the army above political quarrels, Nimeiry established a single-party government, organized sham elections, and in July 1971 decapitated the Communist Party. But his army never offered a real alternative to democracy, nor did it manage to obliterate the old political scene altogether. The Islamists, on the other hand, wanted to establish a sharia state, a regime directly opposed to the Sudan that, in their different ways, the Communists, Taha, and other progressive minds had envisioned. For those minds, the worst-case scenario would be if the army and the Islamists joined forces.

At the start of Nimeiry’s dictatorship, the Islamists were almost as violently persecuted as the Communists. By the late 1970s, however, not only had a rapprochement taken place but Nimeiry’s regime was gradually Islamized. In 1983 it adopted sharia law and imposed Islamization policies on the country as a whole—a move that immediately set off a second civil war with the Southern Sudanese. (The first had ended in 1972, following agreements that promised autonomy for the south.) While war raged in the south, the north fell prey to the totalitarianism of pedantic oppression and penal sharia, which turned daily life into a nightmare. In January 1985 Taha, or Ustaz Mahmoud as he was affectionately known (“Ustaz” means teacher), was arrested for distributing pamphlets that called for the end of sharia law in the country. Refusing to recant his views or even recognize the legitimacy of a sharia court, the elderly intellectual was hanged, only a few months before popular revulsion and a coup finally toppled the regime.

Anticlimactically, what followed was only a brief respite of inept multiparty governance. The big promise was putting an end to the civil war under a national unity government. But a war faction, led by prime minister Sadeq al-Mahdi and including al-Turabi, was pitted against a peace bloc that included left-leaning parties, unions, civil society groups, and the leader of the Unity Party (now the Democratic Unity Party), Muhammad Usman al-Mirghani. In March 1986 a meeting of the peace forces at Koka-Dam, in Ethiopia, concluded that only a secular and democratic state could achieve durable peace. Al Turabi and al-Mahdi sabotaged that initiative, and when al-Mahdi was eventually forced to consent to it—under Western pressure and threats from the army—a segment of the army that the Islamists had infiltrated launched a coup, with al-Bashir at the helm. The situation against which the populace rose in 1985 returned with a vengeance.

*

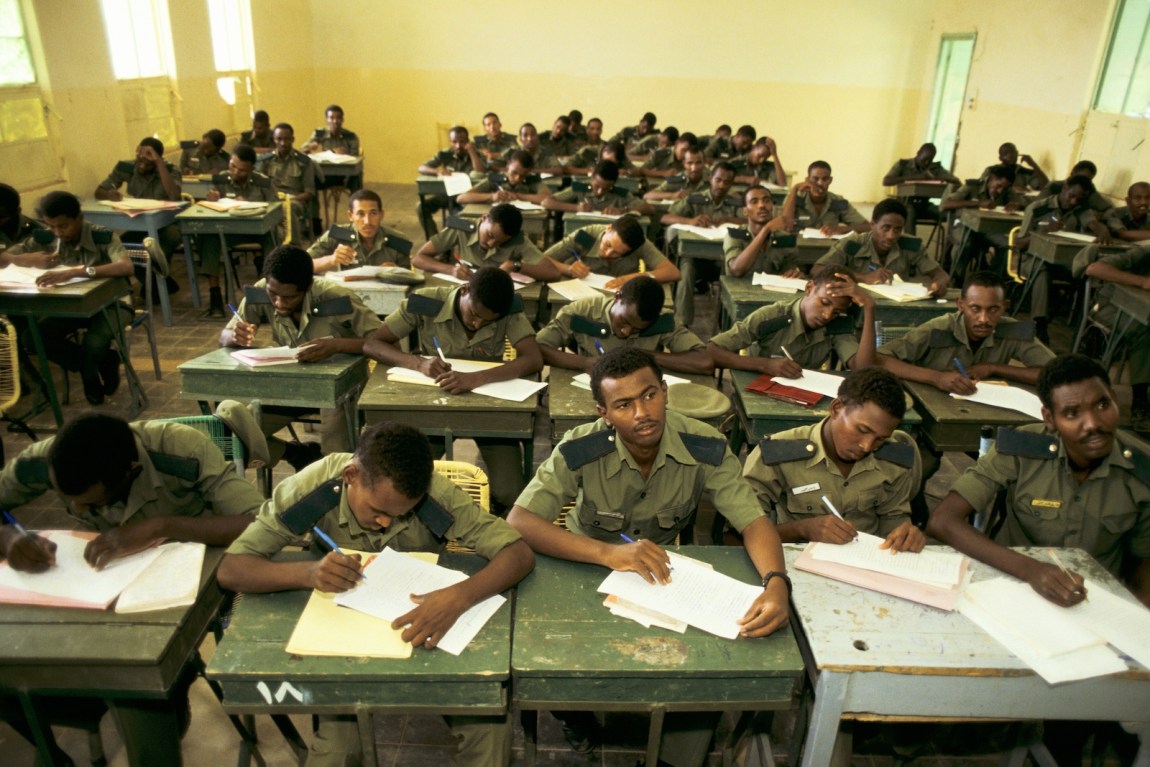

The Islamists’ rule can be schematically divided into two periods, the first ideological and the second acquisitive. During the first decade, an Islamic governance system was established within the state apparatus, with the result that the war in the south continued and democratic politics were prohibited. Al-Turabi became the regime’s master thinker. Under the animating name of al-Mashru al-Hadari (“the civilizational project”), he and his followers attempted a root-and-branch transformation of Sudanese society according to the Islamic principles in which they believed. This involved bellicose audiovisual propaganda broadcast around the clock by state media to instill an us-versus-them fixation in the populace (“them” being the rebels in the south and at some point the non-Arabs in Darfur, but also the great powers to the west and east); the brainwashing of young people in schools and other training grounds; no-holds-barred repression; the unbridled corruption of an elite protected by ideological doublespeak; and the proliferation of parallel organs and shadow forces that subverted the regular state, including its army.

Some words, as the political scientist Ahmed Kodouda has noted, became famous: kashaat, “the street-by-street abduction of young, military-aged men forced to fight a Jihad against their southern compatriots, Muslim and non-Muslim alike”; tamkeen, the “purging of non-Islamists of the civil service, military, and security apparatus”; and “ghost houses,” the torture chambers where the recalcitrant were recalibrated. “Sharia law was to be enforced across all of Sudan, even on non-Muslims.” Al-Turabi understood that for his project to be successful, the Sudanese aspiration for democracy must be wiped out. In 1985, as they had in 1964 and would again in 2018, the people had risen against the military rulers in a fight to reestablish democracy. “The Sudanese people know how to change their governments,” he allegedly mused, according to Kodouda, “so we must change the Sudanese people.”

Eventually a fight broke out between al-Bashir and al-Turabi for control of the vast power their regime had accrued. In 1999 Al-Turabi was unceremoniously ejected from the system in a palace coup, leaving al-Bashir alone at the helm. In the following years, a chastened regime—al-Turabi’s foreign policy of support for the “Islamist international,” including at one point the fugitive Osama bin Laden, had made the country a broke pariah state—reinstated multiparty politics but careened into a disastrous war in Darfur, the periphery par excellence. Non-Arab (Black) communities in the area, who had long suffered under the Arab-Islamic supremacist agenda of Khartoum, revolted in 2001 and proved themselves highly efficient combatants. Unable to fight on two fronts (the war in the south carried on until 2005), al-Bashir outsourced combat in Darfur’s difficult terrain to militias recruited from the Arab or Arabized tribes of the region. Hemetti emerged as a leader of the rampaging militias of the Janjaweed, the armed group with origins in neighboring Chad that participated in genocidal killings across Darfur before later morphing into the RSF.

Sudan was too big and diverse to be ruled from Khartoum as an Arab-Islamic colony, as the regime essentially wanted to do. Al-Bashir recognized as much when he managed to sign a peace accord with the southerners that guaranteed democratic equality between the populations and the possibility of southern independence through referendum. After the southern leader John Garang died in a helicopter accident weeks after being installed as vice president of Sudan in July 2005, partition became inevitable—an outcome that al-Bashir knew not to oppose. But a democratic state was more difficult for him to accept. The eviction of al-Turabi had not only been a palace coup but a full overhaul of the structure of power. The senior Islamists who had been al-Turabi’s companions were sidelined, and their juniors, along with what Kodouda calls al-Bashir’s “trusted friends and tribesmen,” were promoted to strategic posts in the intelligence service, the army officer corps, the patronage organs like Islamic charity organizations, and the army-controlled firms. None of these moves indicated that al-Bashir was coming to embrace democracy.

The changeover did involve an ideological cooldown, but not an end to authoritarian practice. Islamist speech and ritual—including, Kodouda writes, the chanting of “Allahu Akbar” at party rallies and official gatherings—stayed mandatory in the manner of a shibboleth. But the drive was now more acquisitive than doctrinaire, a matter of ensuring the regime’s control over markets like those of gold, rubber, and food exports. Nor was there any question of restoring a national army and ceasing to rely on shadow and parallel security organizations like the RSF. As a Sudanese scholar pointed out to me, Sudan’s army under al-Bashir had turned into a two-tiered caste order where the officers (generals galore) were generally fair-skinned Arabs with the required Islamist credentials, often corpulent, and the foot soldiers undertrained, underequipped, darker-skinned, lankier men from the lower classes who were not expected to rise in rank. If Hemetti’s mercenaries were able to take over Khartoum so rapidly, it was because they were facing this non-army.

And yet all this was nonetheless a more favorable atmosphere for the civilians’ repressed democratic aspirations, which found expression, especially among the youth, in mass demonstrations, agile resistance committees, and music, the arts, and fashion. The powers-that-be made no mistake about the meaning of that last detail, regularly organizing street raids by police, soldiers, intelligence agents, or militiamen armed with blades to cut the long hair of young men: “Are you an artist? A thug? An anarchist? Are you pretty with your girly haircut? Have you strayed from the path of our religion?” Even al-Turabi, in his new persona as an opponent of al-Bashir’s regime, declared in interviews that he had always wanted an “Islamic democracy.” Sudanese critics remarked that, as one put it to Packer, “Turabi killed Ustaz Mahmoud and now he’s stealing his ideas.”

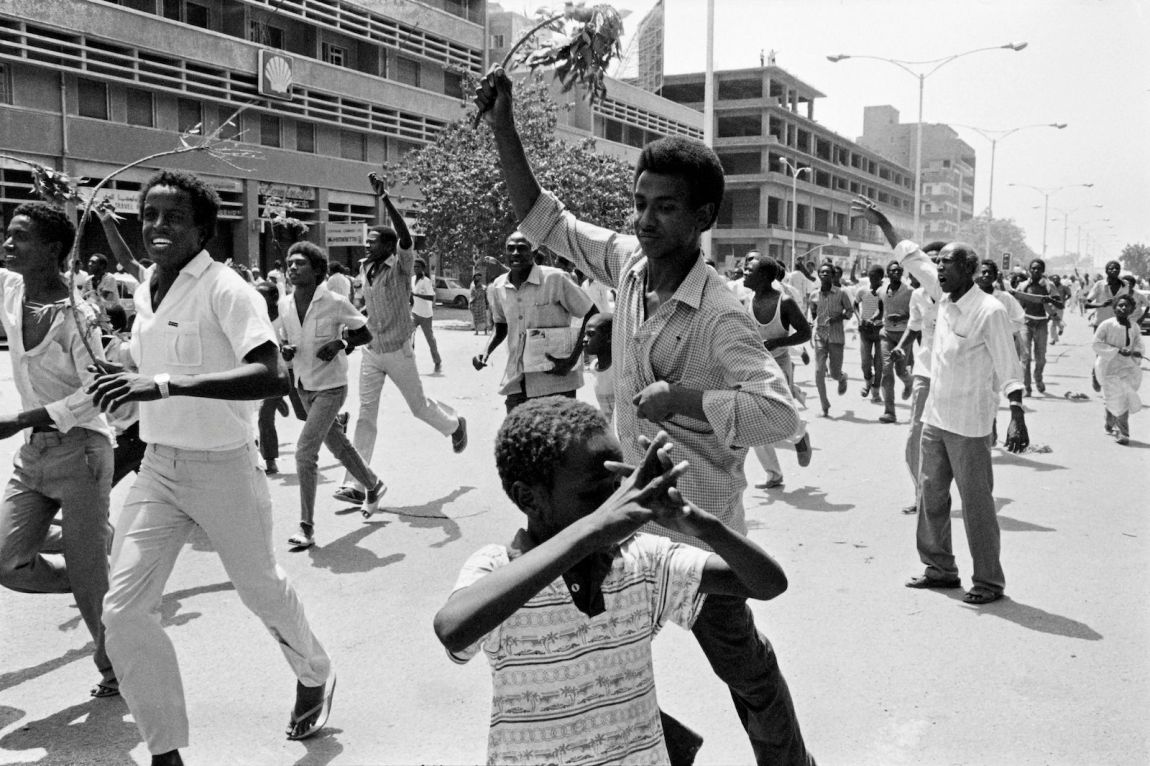

The events of 2018-2019 amounted to an attempted democratic revolution. Bare-handed youth and women were relentless and strategic enough to unseat al-Bashir and force a democratic transition during months of sometimes very dangerous initiatives: organizing demonstrations, including one at the army’s own headquarters, distributing pamphlets, graffitiing buildings, using social media to gather support. They were aided by the fact that al-Bashir’s irregular protection system failed him: in April 2019, Hemetti refused to obey orders to shoot down demonstrators in Khartoum. (Later that year, on the other hand, the RSF had no qualms crushing, in a bloodbath, civilian protesters demanding that the military withdraw from politics.)

Now the “Sudan of the origins” is fighting against itself. In a damning recent essay for the London Review of Books, Alex de Waal sees this as a revolution rejected. Instead of a democratic transition, he argues, the center’s depredations are coming home to roost in the vengeful guise of one of the periphery’s best-armed sons. But Hemetti and al-Burhan ultimately belong to the same military-Islamist apparatus, which is finally exploding in the face of its internal tensions. The real struggle is ultimately between them and the unarmed democratic revolutionaries. Those revolutionaries have been shoved to the sidelines now. But nothing in Sudan’s history says they will ever give up.