Theater performances always have a settling-in period, those tortured or merely awkward first minutes in which the audience hasn’t quite left behind the world outside. The length and difficulty of the adjustment often correlate with the distance between the play’s language and setting and our own. Even, or maybe especially, in a good Shakespeare production, one can spend the first act panting to catch up. In a performance of Beckett, the difference between alienation that’s intentional and boredom that results from incompetence might take even longer to resolve.

Acclimating to a Tennessee Williams play requires accepting both a heightened, nearly hallucinatory romanticism and a range of accents, mostly southern, that will almost inevitably cause some initial degree of confusion and hilarity. In Theatre for a New Audience’s current production of Williams’s rarely revived 1957 play Orpheus Descending, directed by Erica Schmidt, the disharmonious chorus of voices onstage loudly declaring their loyalties, histories, and passions is an arduous barrier to entry. That the play nevertheless often succeeds speaks both to Williams’s ability to wrest beauty and surprise from even a muddled scenario and to the actors’ skill at bringing specificity to roles poised between caricature and myth.

At the center of the play is the gradually shifting relationship between Lady Torrance (Maggie Siff), an Italian immigrant’s daughter who is married to a dying shop owner in a small southern town, and Valentine Xavier (Pico Alexander), a Lead Belly–worshipping musician looking for a job in the shop, who seems to have been, among other things, a male hustler in a past life. Their dynamic seems to echo those in Williams’s better-known work—Lady’s invalid husband, whose frequent thumps on the ceiling reverberate throughout the play, contains elements of both Big Daddy and his son Brick in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, and the fraught dance of outsiders suggests more than a hint of the battle of wills between Blanche and Stanley in A Streetcar Named Desire. (Marlon Brando even played Valentine in The Fugitive Kind, Sidney Lumet’s 1960 film adaptation of Orpheus Descending.) In fact, aspects of the play predate those milestones. Orpheus Descending was a long-gestating revision and expansion of Battle of Angels, which had its brief run in 1940, four years before The Glass Menagerie established Williams as a major American playwright.

Lady, we learn, was engaged years ago to David Cutrere, the son of a prominent local family, and secretly pregnant with his child. Then her father was murdered and his orchard and wine garden burned to the ground by a Klan-like posse after he sold alcohol to Black customers. The scandal of her father’s murder led Cutrere to abandon her, driving her to get an abortion. Her dream is to recreate her father’s gathering place in the store’s disused confectionery, in defiance of her ailing, racist husband. Valentine’s mysterious arrival—and his sexual and romantic prowess—inspires her to renew her investment in the project and in her life.

This is already enough to sustain a full-length play, but Williams piles on the characters and subplots, turning the piece into an off-kilter epic, grand in its ambition but somewhat fuzzy in its formal mechanics. The third primary character is Carol Cutrere (Julia McDermott), David’s “wild,” alcoholic sister, who has been forbidden from setting foot in the county for, among other things, marching on the state capitol in a burlap sack to protest the execution of a Black man for allegedly having “improper relations” with a white woman. There’s also the sheriff’s wife, Vee Talbott (played by the brilliant, scene-stealing Ana Reeder), who wanders in and out of the store with naive paintings based on her religious visions, and, most uncomfortably, an indigent Black “conjure man” named Uncle Pleasant (Dathan B. Williams), who is prompted at various points to deliver his “Choctaw cry.”

Tennessee Williams’s work is famously sympathetic to outcasts, especially men and women who refuse to conform to society’s sexual mores, and part of the curiosity of Orpheus Descending is the way it links this interest explicitly with racial justice. The play’s misfits are united by the distrust and hostility they engender due to their proximity and sympathy to Black people. (“Jim Crow killed Bessie Smith,” Val says at one point. “She bled to death after an auto accident, because they wouldn’t take her into a white hospital.”) Williams’s moral clarity is bracing and unequivocal, no simple matter for a southern writer of his time. It’s nevertheless a testament to the limits of that clarity that the play’s heroic martyrs to racial justice are all white—though Lady is ambiguously so in this time and place—and that Uncle Pleasant’s role is largely to serve as a mute physical reminder of the horrors enacted upon the Black population.

Advertisement

*

Orpheus Descending is both dreamlike and didactic, a romance crossed with a “social issues play” that never settles into a comfortable or conventional form. As becomes clear in the brutal third act, Williams’s aim is ultimately operatic in scope. Lady learns that her husband was part of the posse that killed her father and subsequently reveals to Val that she is pregnant with his child. As her husband nears death, she insists on holding the grand opening of her bar to spite him in his last moments. The play culminates in the murders of Lady and Val, graphically illustrating the consequences of bucking the codes of southern propriety.

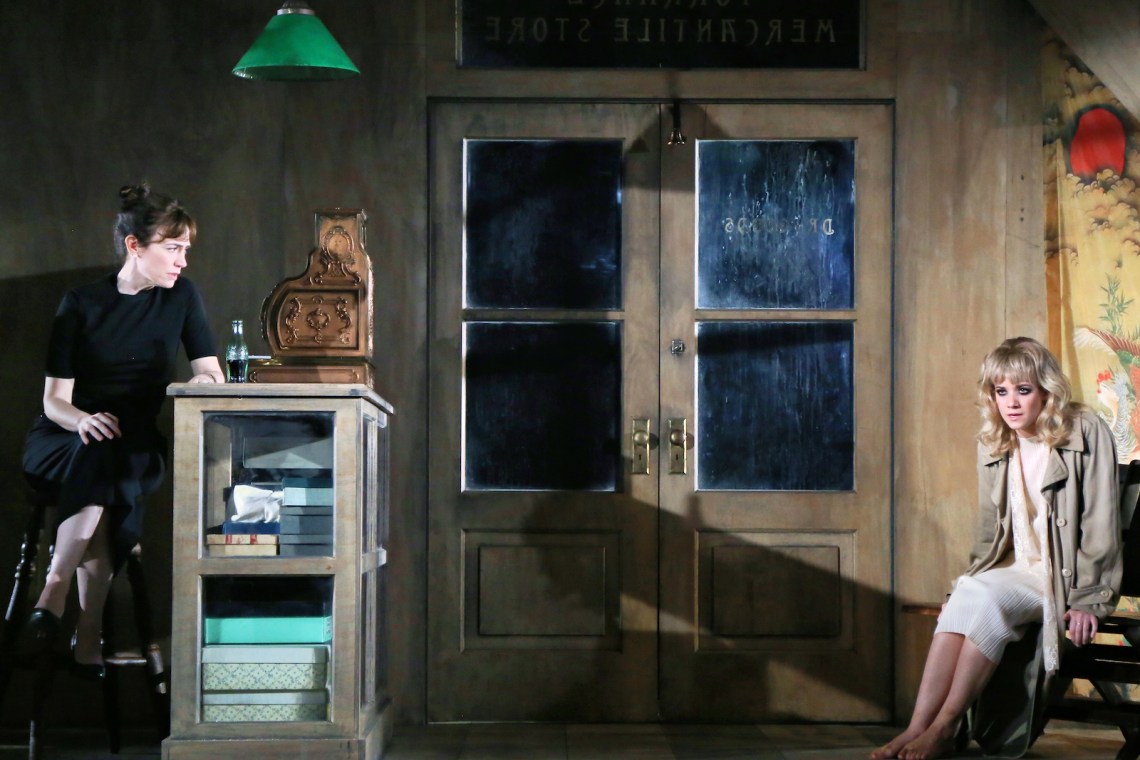

At Theatre for a New Audience, the staging retains the contradictions and oddness of the text without smothering it in ironizing camp or smoothing it over into something more digestible. As written, Valentine and Lady are in danger of seeming more like ideas—the drifter, the immigrant—than real people, and the cascading plot (pregnancy! revelations! betrayal!) lands them squarely in the realm of gothic melodrama. But Alexander and especially Siff imbue their roles with the gravity and wit required to sell a musician who straight-facedly calls himself “Snakeskin” (on account of his snakeskin jacket) and an Italian woman who refers to her beloved father as a “Wop bootlegger” who sold “dago red wine.”

It’s no small task to drag what remains, in many ways, a product of its time over the line into something emotionally true, but Siff’s wounded intensity is consistently plausible and affecting. We need to believe that Lady’s recklessness—carrying on an affair literally beneath her husband’s feet, in full view of a vicious southern community, all the while refusing to obey its racist strictures—is driven by an inner necessity and not just by the requirements of the play’s plot and politics. Siff achieves this by embodying a barely repressed fury from the start. Val might be the catalyst for her actions, but the hokeyness of this nearly magical character is transcended by Siff’s choice to make it clear that it wouldn’t have taken much to set her off.

Because of the occasional limitations of the source material, a faithful production of the play, even with excellent acting and direction, can only be at most a partial success. But one of the absorbing things about watching it unfold is clocking the friction between the emotional immediacy that the actors are able to convey and the imperfect vessel in which they deliver it. One imagines that the creative team was drawn to the play’s defense of racial and sexual outsiders, which resonates painfully in this moment of violent discrimination against transgender people, racial minorities, and migrants. I found myself admiring the bluntness of Williams’s language and scene-making, as when Lady, in a blind fury near the play’s end, screams that she doesn’t even want to open her bar, but that “it’s just something’s got to be done to square things away, to, to, to—be not defeated! You get me? Just to be not defeated!”

The bluntest character, and the most difficult to assimilate, is Carol Cutrere. As the outspoken, damaged scion of privilege, she is in some ways a familiar figure (some of my best friends are outspoken, damaged scions of privilege!), and McDermott plays her big, swaying blowsily around the stage in a trenchcoat and declaiming forcefully about the pleasures of juke joints like an Ophelia in her mad scene. The performance feels like a tribute to the Method heyday in which the play was written—there’s more than a little Misfits-era Monroe in her mix of seductiveness and desperation. If Siff brings the play a classical realism (despite a strange intonation, which shades more Eastern European than Italian) and Alexander a sly, even goofy charm, McDermott seems determined to blow past the tenets of good taste and leave blood on the floor. Why should she be bound by conventional manners, she seems to ask, when nothing about the world around her deserves them?