Sinéad O’Connor passed away on July 26, 2023, as this essay was being edited.

Nothing Compares, the documentary about Sinéad O’Connor directed by Kathryn Ferguson and released last year, opens with her 1992 appearance at a tribute concert for Bob Dylan. We hear O’Connor announced off-camera by Kris Kristofferson, then watch her step out in front of a sold-out crowd at Madison Square Garden. At once the crowd breaks into a roar: half of them cheering, and half of them very audibly booing. She stands facing the wave for a minute or more, an eternity of stage time, her eyes bewildered and wounded, seemingly just short of tears, but her face a mask of stoic determination. In a present-day voiceover, she gives a brief, matter-of-fact introduction: “I did suffer through a lot, because everybody felt it was okay to kick the shit out of me. I regret that I was so sad because of it.” It’s hard to argue with that assessment. O’Connor’s celebrity peaked at a time when artists had very little control over their public narratives, and for much of her career the media, the public, and many other musicians were unkind to her, or even cruel.

Two myths have long persisted about O’Connor. One is that she was a one-hit wonder, that her success began and ended with her chart-topping cover of Prince’s “Nothing Compares 2 U.” The other is that her career was placidly chugging along until in 1992 she decided, apparently out of nowhere, to pull out a photo of then-pope John Paul II and tear it up while staring directly into the camera on Saturday Night Live. But neither is true. She was already a Grammy nominee when she recorded the cover, and she had stirred up considerable enmity in the music business and the entertainment press before the SNL appearance was ever booked. Later the documentary comes back to the Dylan concert to show O’Connor’s response to the booing: Ripping out her ear monitor, she delivers a defiant, scornful, but uncharacteristically tremulous rendition of Bob Marley’s “War,” the same song she had performed on SNL two weeks earlier.

Well received at Sundance last year, Nothing Compares was made with O’Connor’s cooperation; she declined to appear on camera but provided extensive narration. The documentary was released soon after her memoir, Rememberings (2021), a bestseller. Evidently she had decided to become the narrator of her own story, long ventriloquized by voracious media, lazy stand-up routines, and 1990s nostalgia. “To be understood was my desire,” she writes in the book’s foreword. “Along with that was my desire not to have the ignorant tell my story when I’m gone. Which was what would have happened had I not told it myself.”

*

Born in a Dublin suburb in 1966, Sinéad O’Connor was the third of five children. Her mother was severely abusive. “My mother was a very violent woman,” she says, “not a healthy woman mentally at all.” In Nothing Compares O’Connor describes those years of abuse in generalities leavened with nonchalant, brutal detail. O’Connor was forced to sleep in the yard outside the house, watching as the lights inside disappeared one by one when her mother went to bed. This experience was one of two stories woven together in her most spectacular early achievement, the song “Troy” from her debut album, The Lion and the Cobra (1987). Its searing string-driven climax climbs from a strident accusation to a desperate shriek: “You should have left the light on! You should have left the light on!”

She was not yet twenty when she wrote it. “It’s not a song,” O’Connor reports flatly in the documentary. “It’s a fucking testament.” The title is a reference to Yeats’s 1910 poem “No Second Troy,” which begins “Why should I blame her that she filled my days/With misery,” and concludes “Why, what could she have done, being what she is?/Was there another Troy for her to burn?” O’Connor answers Yeats with a bitter refrain: “There is no other Troy for you to burn.”

O’Connor’s parents separated when she was eight. Her father was given custody, but Sinéad and her younger brother insisted on going back to their mother, and were subjected to years of further abuse before returning to their father’s house. A sincere and devout Catholic child who grew into a “difficult” young adult—she was encouraged by her mother to shoplift—O’Connor was remitted to the care of nuns when she was fourteen: “I was unmanageable, really, so they didn’t want me at home,” she said. The “care home” was in fact a recent rebrand of one of Ireland’s notorious Magdalene laundries run by the Roman Catholic Church. Between the eighteenth and twentieth centuries tens of thousands of Irish women, pregnant and unwed or simply, like O’Connor, deemed “difficult,” were disappeared into such institutions. In addition to their incarceration and punitive abuse, the women were used as forced labor.

Advertisement

Her musical education began, she later said, in her parents’ extensive record collections, which included both classical music and Porgy and Bess. When she was eleven, an older brother bought Dylan’s Slow Train Coming. It made young Sinéad want to be a musician. Despite the horrors of the laundry, one of the nuns encouraged the young singer’s talent, buying her a guitar and a Dylan songbook for beginners and finding her a guitar teacher. An incredible home video shows a fifteen-year-old Sinéad singing Barbra Streisand’s “Evergreen” at the teacher’s wedding, then smiling angelically as she leaves the church. In the audience were members of In Tua Nua, a local band that was looking for a singer, who approached her on the church steps. To record O’Connor’s vocals for their first single, “Take My Hand,” they snuck her out of the care home for two hours. “Take My Hand” was also the first song for which O’Connor ever wrote the lyrics, and in the documentary she explains that she drew from a personal experience of being punished. A nun

sent me to sleep in the hospice part of the laundry as punishment a couple of times, to remind me that if I didn’t behave myself I was going to end up like these women. When I went up, there was no staff there with the ladies…. And the poor ancient ladies who were the Magdalene girls were lying in the beds calling out for nurses all night that never came.

The violence inflicted by the Catholic Church not only on the Magdalene women but on all of Ireland and Irish history is a running theme in O’Connor’s lyrics. In the documentary she reflects on the link between the personal abuse she suffered as a child and the systemic abuses of patriarchy and religion:

The cause of my own abuse was the Church’s effect on this country, which had produced my mother. I spent my entire childhood being beaten up because of the social conditions under which my mother grew up, and under which her mother grew up, and under which her mother and her mother grew up.

In early adulthood O’Connor moved away from the church and became an outspoken critic, only to later embrace a heterodox branch of Catholicism not in communion with Rome, in which she was ordained as a priest. She frequently expressed her long fascination with Rastafarian religion and music, and in the 1990s, like many celebrities, she flirted with pop-kabbalah. “There isn’t any answer in religion, don’t believe one who says there is,” she sings on 1997’s “Petit Poulet.”

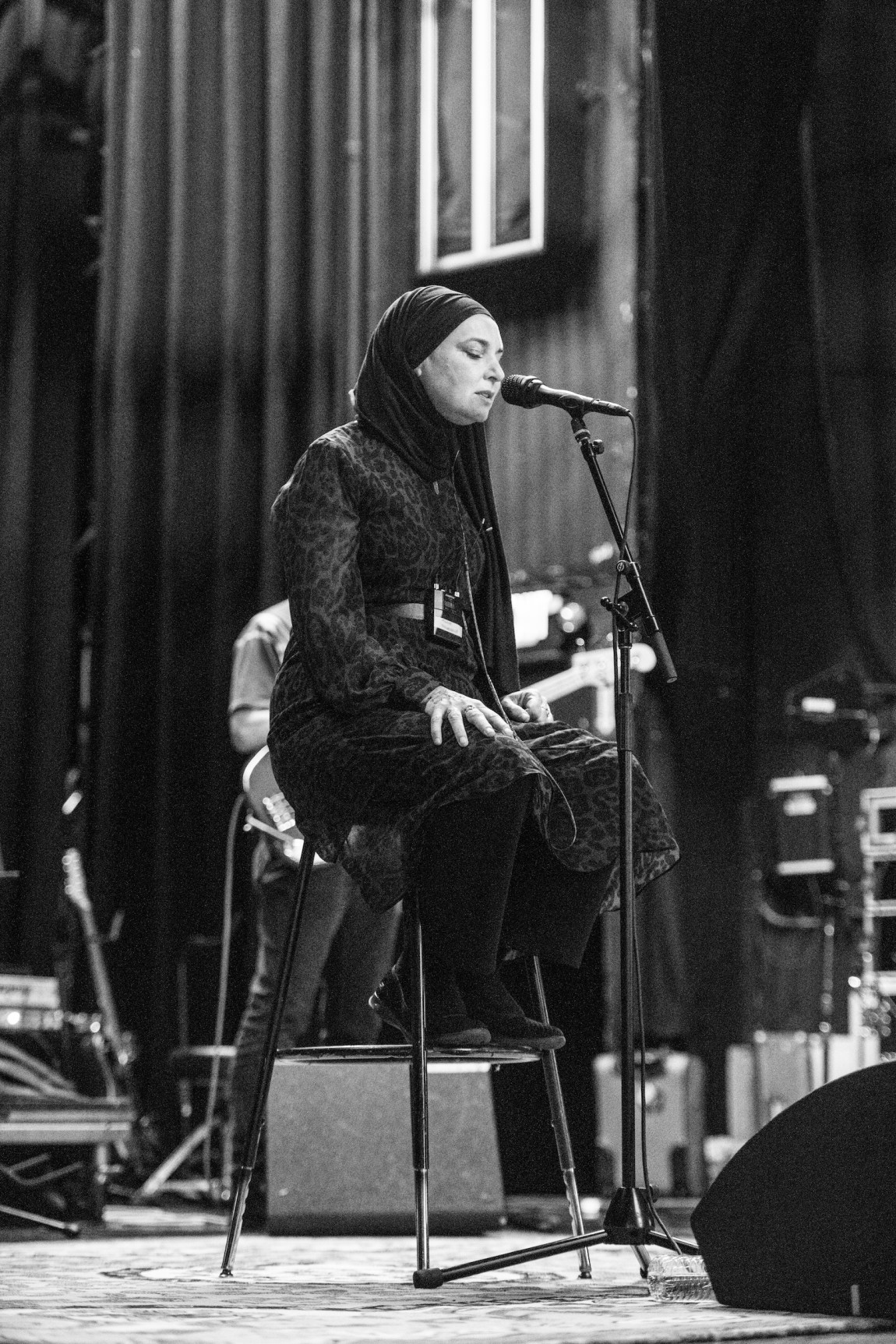

But skeptics often make the most determined seekers, and she never stopped asking questions. A 2007 album was titled Theology; its lyrics are a bricolage of verses from the Old Testament. In 2018 O’Connor converted to Islam, announcing on Twitter that it was “the natural conclusion of any intelligent theologian’s journey” and taking the name Shuhada’ Sadaqat. (She continued to used the name Sinéad O’Connor in her professional endeavors.) The same year she wrote a public letter to Pope Francis asking him to excommunicate her. In recent years she performed in a hijab when on tour and spoke often of the comfort she found in Islam.

*

At sixteen O’Connor moved to Dublin with her father’s reluctant blessing and put out ads in music magazines, looking for a band in need of a singer. She joined one with the name Ton Ton Macoute; a number of similarly unfortunate appropriations pepper her career. On the strength of the band’s live performances, Ensign Records invited her to London to cut some demos, but without the rest of the band. The label had been founded in 1976 by Nigel Grainge, who was British but found considerable success with Irish acts. In his previous job as an A&R man he had signed Thin Lizzy, and at Ensign he guided the career of the Boomtown Rats; in her autobiography O’Connor credits Bob Geldof as the first man to sing on the radio with an Irish accent.

An entertainment lawyer begged her to find a better deal than the seven points Ensign offered, but seven points seemed like plenty to a working-class teenager, and she signed a contract that gave her creative control but put the profits from her biggest hits squarely in the hands of record executives. A mutual acquaintance connected her with the industry veteran Fachtna Ó Ceallaigh, who had managed U2, among others, and became her manager for the first years of her career. She also met John Reynolds, who became first her drummer, then her lover and co-conspirator, then the father of her first child, then her husband, then her ex-husband, and ultimately a lifelong friend and collaborator. “I’d be lost without John in my life,” she writes in her autobiography.

Advertisement

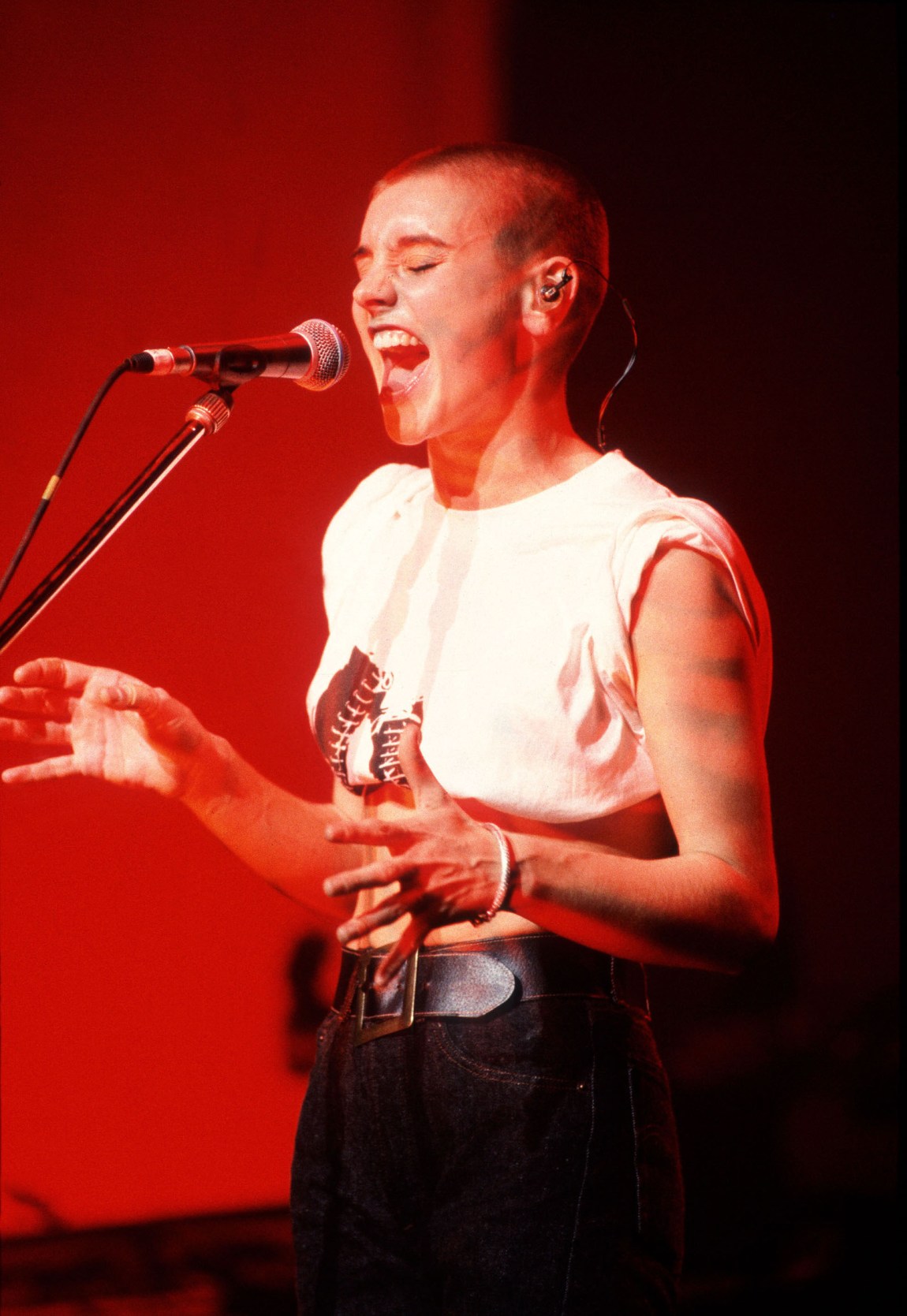

In the wedding performance video, O’Connor’s voice is beautiful but not immediately recognizable. But rehearsal footage from 1985–1986 shows the hallmarks of her familiar vocal style already in place. The most important of these is her clarity of tone, with virtually no vibrato, distinctly out of step with the “soulful” affectation of most late-twentieth century pop vocalists. When Sinéad O’Connor grabs a note, it stays put for an impossibly long time without the slightest waver. This purity is reminiscent of bel canto, which she did study, but only in the mid-1990s. She glides effortlessly between notes; there’s seemingly no attack or rise, she’s just there, on the next one: “No-thing compares….” But she’s also capable of dramatic and unexpected dynamic leaps, erupting from a whisper to a frenzied yowl.

Another signature, especially on early tracks, is an extended, lupine howl that shifts sound halfway, resulting in an anguished “aaaaaooooooohhhhhhhh” (you can hear it on “Jerusalem,” and on the repeated “light oooouuuuunnn” at the end of “Troy”). She also deploys her accent strategically, switching between rounded American vowels and sharper Irish ones, sometimes mid-word. It’s hard to imagine The Cranberries’ “Linger” on American radio without O’Connor’s precedent; evidently she thought so too, which led to a long-simmering rivalry with the late Cranberries singer Dolores O’Riordan. On earlier recordings especially, the roar of her voice can be explosive, but even then it’s rigorously controlled. Unlike some equally powerful singers, she never seems overwhelmed by the emotions she’s calling forth; their conjuring feels like an act of mastery. “You often hear artists saying that they’re channeling something,” she says in Nothing Compares. “I think actually you’re channeling yourself.”

In London the young Irish transplant encountered Black and gay cultures for the first time. Ó Ceallaigh brought her to Portobello Road, introducing her to London’s thriving reggae scene. “Bear in mind I’m Irish, I’ve come from the theocracy. And these guys come along roaring about the Pope is the devil and fucking burn the Vatican and all this stuff, so that was like ‘Oh my God, I’m home.’” O’Connor’s fascination with Rastafarian culture and with Jamaican music, especially reggae and dub, culminated in the roots reggae covers album Throw Down Your Arms (2005), recorded in Kingston and produced by no less than Sly and Robbie, with whom O’Connor went on tour. But the influence can be felt throughout her discography, most obviously in the thick slabs of dubby bass that anchor songs like “I Am Stretched on Your Grave” and “Fire on Babylon.”

Given O’Connor’s reluctance to be told what to do, clashes between the artist and her label were probably inevitable. “They wanted me to grow the hair long and wear short skirts and high heels,” she recalls in the documentary. Instead she shaved her head. While writing and rehearsing for what was supposed to be her first album, O’Connor became pregnant. “The record companies in those days had their own doctors that they sent you to,” she says. “The doctor announces that the record company have spent £100,000 on making your record, you owe it to them not to have this baby.” The doctor’s framing was deceptive: standard industry practice even today allows labels to recoup recording expenses from an artist’s earnings before paying out, so it was actually her own money that O’Connor had spent on recording.

Resisting the pressure, O’Connor decided not only to keep the baby but also to scrap the album. “It ain’t worth it for a shit fuckin’ record,” as she puts it in Nothing Compares. “I just knew that I didn’t want any man telling me who I could be or what I could be or what to sound like.” She gave birth to her son Jake in 1987, the first of four children with four fathers. In Rememberings O’Connor describes being able to enjoy motherhood without the limitations and strictures of marriage, and the comedy of negotiating Father’s Day in her household, a mode of life unthinkable to Irish women a generation before her.

*

While still pregnant with Jake, O’Connor started work on her debut album from scratch, firing the label’s preferred producer and producing it herself. Reynolds observes in Nothing Compares that “the second version was fresher, younger, and spontaneous.” The Lion and the Cobra was a remarkable and notably successful debut. The title is drawn from the New King James translation of Psalm 91:

Because you have made the Lord, who is my refuge,

Even the most high, your dwelling place,

No evil shall befall you,…

You shall tread upon the lion and the cobra,

The young lion and the serpent you shall trample underfoot.

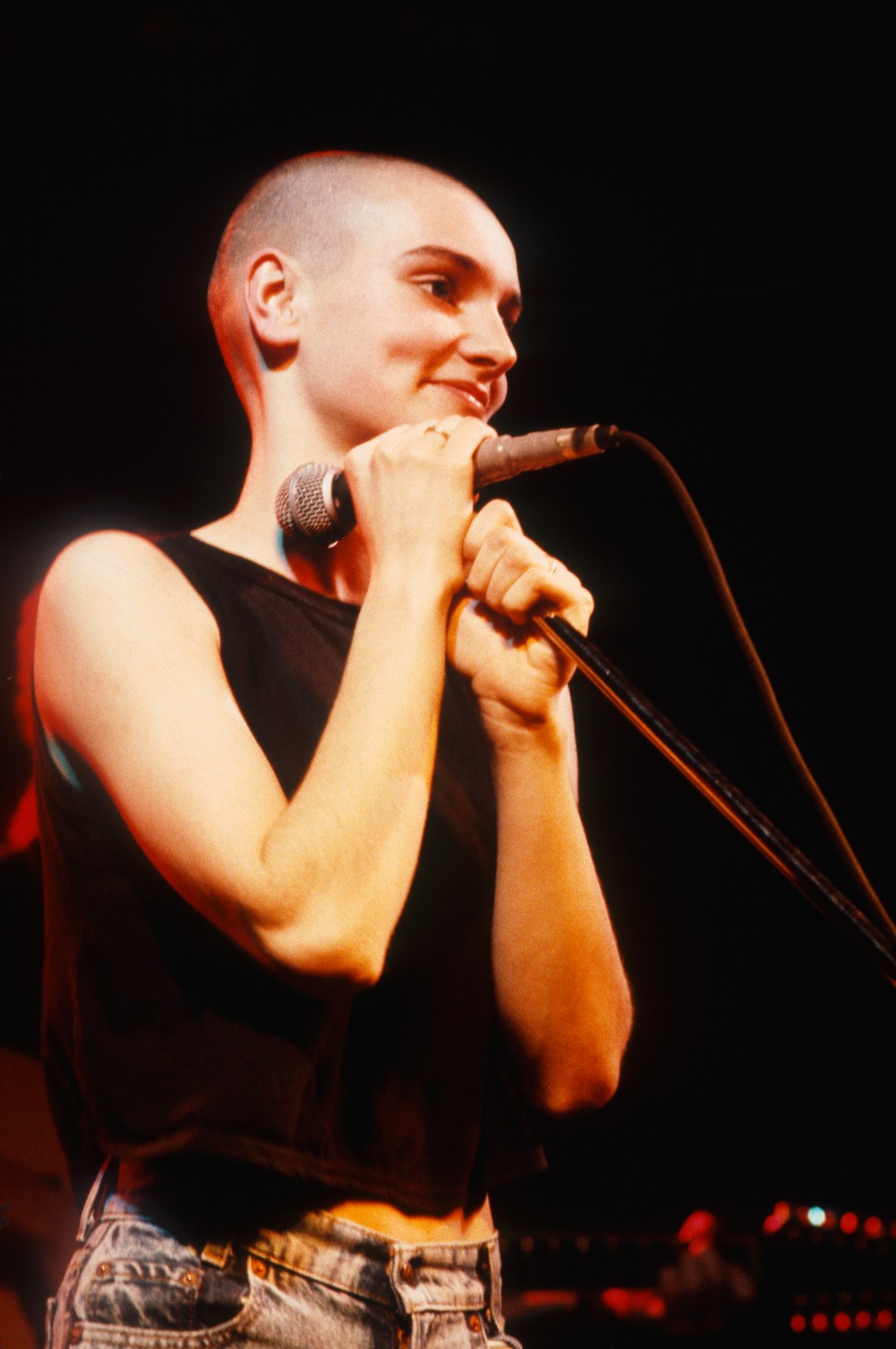

On the album’s original cover, a shaven-headed O’Connor snarls in what looks like rage (in fact, she reveals in the documentary, she was just singing along to her music). For the US release the image was swapped with something more demure: the singer gazing down, arms crossed across her torso, looking vulnerable and defensive. Both photos were taken from the shoulders up, because O’Connor was by then very pregnant. Nonetheless, in several striking full-body portraits from this period, she heralds the hairless, ambisexual CK1 vibe of the decade to come. A phenomenal 1987 image by Kate Garner shows her from above, grinning impishly, heavily pregnant and wearing a cut-off tee that leaves her belly bare and reads WEAR A CONDOM.

All songs on the album were written or cowritten by O’Connor—several, including the opener, “Jackie,” and the anthemic “Drink Before the War,” when she was still a teenager. Widely lauded for her voice, O’Connor also deserves acclaim as a songwriter. There’s a deep sentimentality woven into many of her songs, which at its worst can be cloying and cheesy but rarely naïve, and is often wielded with intent; in Rememberings she fairly cautions against assuming any given song is written from her own perspective. Many are autobiographical, but not all, and not always the ones you think. Still, the majority feel confessional and raw, making O’Connor an important predecessor to the blunt, intimate lyrics that typified the 1990s rock grrrl, from Liz Phair and Courtney Love to Alanis Morrissette. There are brutal truths hidden in the soft folds of O’Connor’s ballads.

The Lion and the Cobra doesn’t fit comfortably in any genre, but the strong production gives it a uniform pop-rock sheen, and just enough of it sits at the intersection of quirky and funky that radio found irresistible in the 1980s. “I don’t know no shame, I feel no pain” O’Connor growls fiercely on “Mandinka,” a hook-filled slice of Smiths-y jangle-pop, and you believe her. Nonetheless, a number of songs carry a palpable burden of hurt. “Jerusalem” alternates shimmering wah-wah funk in the verses with a celestial chorus. It’s very close to being a pop song, until you get to the breakdown, during which O’Connor bursts into eighteen seconds of increasingly frenetic yelps, before shifting back to the chorus as if nothing happened. It’s the kind of album that only happens when a young artist has a big-label budget and a contract that guarantees creative control.

The lead single was “Troy,” which had modest success in the Netherlands and Belgium but otherwise did little. Greater exposure came with a prominent soundtrack placement in A Nightmare on Elm Street IV for the slinky, cowbell-heavy “I Want Your (Hands on Me),” and from the second single, “Mandinka,” which was a minor hit. (The song’s title is finally explained in Rememberings: she had recently watched Roots). Then a much bigger coup: The Lion and the Cobra was nominated for a Grammy for “Best Rock Vocal Performance, Female,” alongside Tina Turner, Toni Childs, Melissa Etheridge, and Pat Benatar (Turner won).

At twenty-one O’Connor performed “Mandinka” at the awards show in Los Angeles. Video of the number—O’Connor shimmying confidently in a halter top, torn jeans, and black Doc Martens, alone onstage without a band—gives the lie to any notion that the grunge aesthetic of the 1990s owes everything to Seattle. She went onstage with Public Enemy’s target logo painted on the side of her head in solidarity with the band, who had decided to boycott the awards. “You didn’t get the sense that she was just being pretentious, that she was fake,” affirms Chuck D in a voiceover. O’Connor’s reward for the success of The Lion and the Cobra was a bigger budget and less interference for her next LP. The result was I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got (1990).

*

Each of O’Connor’s albums includes at least one cover, and on her second that cover was “Nothing Compares 2 U,” written by Prince and recorded by the Family for their self-titled 1985 debut album. It turned her from a promising up-and-comer into a global pop sensation—putting her in the center of the celebrity machine and the vicious, voracious tabloid journalism of the 1990s—and cemented for eternity her place in the canon of drunk karaoke songs. The famous tear she sheds in the video, it turns out, was unplanned, a spontaneous emoting while filming the close-up shots. “I think it’s funny that the world fell in love with me because of crying and a tear,” O’Connor says wryly. “I went and did a lot of crying, and everybody was like ‘Oh, you crazy bitch, but actually, hold on.’” The single went number one across the world. A planned theater tour of the US was quickly rebooked as an arena tour.

Made at the meeting-point of two decades and blending much of the best of both, I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got was produced like a 1980s album, with cavernous kick drums and thick basslines high up in the mix, but it gestures toward the 1990s with spiky alt-pop numbers, like “The Emperor’s New Clothes” and the proto–PJ Harvey grind of “Jump in the River.” Opening with the slow-building symphonic sweep of “Feel So Different,” the record announces its intent from the first line: “I am not like I was before.”

It was only her second album, and she was only twenty-three when it was released, but O’Connor had by then lived a lifetime and would go on to live several more. Transformations, rebirths, and epiphanies recur across her records. Completely different but no less dramatic is the second song, “I Am Stretched on Your Grave.” Over a loop of the famous “Funky Drummer” drum break, a wet, wobbly bass line, and little else, a strident, ethereal O’Connor floats in a lake of reverb while intoning an English translation of the anonymous seventeenth-century Irish poem “Táim sínte ar do thuama.” Samples in pop music have come a long way, but it was an audacious move in 1990. “Black Boys on Mopeds” quietly shows that in the realm of pop music, at least, O’Connor was as far ahead of the curve on police racism as she was on clerical abuse. The hidden jewel of the album’s recording sessions is a spectacular rendition of Etta James’s “Damn Your Eyes,” released as a b-side in 1990 and added as a bonus track to the album’s 2009 remaster. The song is one of O’Connor’s finest vocal performances, the sultry, angry counterpoint to “Nothing Comparies 2 U.”

O’Connor’s first taste of controversy came during the US leg of the album’s tour. Performing at the Garden State Arts Center in Holmdel, New Jersey, she asked that “The Star-Spangled Banner” not be played before her show. In her memoir, she describes the event as a misunderstanding with her typical dry humor:

Two Caucasians (as they say in America), one male and one female, came to my dressing room. They asked me how I would feel about “The Star-Spangled Banner,” the American national anthem, being played through the speakers before I perform.

Now, mea culpa, but because where I come from we speak English, I gleaned from the phrasing of their question and from the fact that they put it as a question at all that what they were saying was if I didn’t feel cool about it, that would be cool…. But the whole thing was an extraordinary setup. While I was onstage, the two sleeveens called a local television news show and created a nationwide fuss by falsely reporting that I had sought them out and demanded the anthem not be played before the show. They also claimed that I told them I would not go on if it was played. Which is entirely untrue. One’s tour insurance would never cover one for such a decision.

The American media seized on the incident with the kind of obsessive fervor that used to be devoted to such nonsense in the days before the US was ready to admit it had bigger problems. Frank Sinatra, always a gentleman, announced that he wanted to “kick her in the ass.” MC Hammer publicly mailed her a first-class ticket back to Ireland. There are photos of the young singer in a wig with nose-length bangs attending a protest against herself outside a venue, amused and nonchalant.

O’Connor began using more and more of her airtime to speak out on hot-button issues, first among them the abuse of children under the aegis of the Catholic Church. At the thirty-third Grammy awards that year she was nominated in four categories, including Record of the Year. She decided to boycott the ceremony and later refused the award she did win, for “Best Alternative Music Performance.” She took the same tack with every other ceremony, award, and nomination her smash record received: “I make plain as I’m refusing awards and award shows that I am doing so in order to draw attention to the issue of child abuse. And that I’m a punk, not a pop star.”

O‘Connor’s decision to put child abuse and the Church’s deleterious effect on the family at the front of her public relations agenda had probably predictable results. Hardly unmotivated, the SNL incident came after two years of responses that ranged from stonewalling to mockery. In interviews from her early twenties O’Connor is a credit to herself, remarkably calm and collected when laying out her beliefs and opinions—about the music industry, about the Church, about Northern Ireland—to a sneering media that insisted on portraying her as shrill, thankless, and petulant. Her composure is always admirable, even when her eyes are darting around, looking for the nearest exit.

At every step the indignation she aroused only pushed her to further defiance. Her memoir repeatedly characterizes these moments as expressions of plucky Irish stubbornness, but it’s also clear that not all her decisions were equally reasoned: there were a lot of emotions involved, and also some drugs. It’s also impossible to deny that O’Connor was subjected to a kind of disdainful scorn and casual abuse by the media that neither a male artist nor, indeed, a more rigorously gender-conforming female artist would have ever encountered. She kept kicking against the pricks, and the pricks must have felt embarrassed by the short, shaven-headed Irish upstart who refused one of the global media-industrial complex’s highest honors.

It certainly didn’t help that the primary cause to which O’Connor dedicated her recalcitrance was unmentionable in polite company in 1990. “I was always being crazied by the media,” she says in Nothing Compares. “I don’t blame anybody for thinking I was crazy…. It was a crazy idea, this bitch is saying that priests are raping children. I mean, Jesus Christ, of course it seemed crazy to them.” In a 2010 interview with the Canadian CBC, she pointed out that the public conversation over abuses in and by the church began in Ireland several years before it began in Canada or the United States. In the decades since, it’s come to light that not only did the Church know about these global, systemic abuses, it also maintained a policy of shifting priests around from parish to parish and shielding them from investigation instead of removing them from office.

*

At once buoyed by the smash success of her second album and buffeted by controversy, O’Connor quickly recorded her third album, Am I Not Your Girl? (1992), which was, to everyone’s surprise, a collection of covers, mostly big band numbers like “Why Don’t You Do Right?” and “I Want to Be Loved by You.” It also includes a rendition of “Don’t Cry for Me Argentina” and an instrumental version of the same cover. For years I puzzled over that decision, until I learned from the memoir that it was a song O’Connor used sing to her mother to calm her and lull her to sleep. Am I Not Your Girl? is not her best, though it has its moments, most notably a version of “Success Has Made a Failure of Our Home,” originally by Johnny Mullins and made famous by Loretta Lynn. O’Connor’s vibrato-less tones sit uneasily atop a big swinging bop. In retrospect the album was both a creative holding pattern and an escape hatch from expectations: “I was kind of buying myself some time,” she says in the documentary.

Releasing the album in September, O’Connor embarked on the promotional trail and was scheduled to play Saturday Night Live. “I took two things out of my mother’s house,” she says in the film. “One was her cookery book, and the next was a picture of the Pope which had been on her bedroom wall.” Wearing a Star of David pendant, O’Connor delivered a searing a cappella rendition of Marley’s “War” before pulling out the picture, tearing it up while staring directly into the camera, and then throwing down the pieces, declaring, “Fight the real enemy.”

In an interview filmed the next day she seems sanguine about the act and its consequences, though at least some of it must have been exhaustion. But the fallout was significant. The incident made global headlines; twenty-four-hour news networks spun the story for days; Catholics threatened boycotts. The artist, her band, and her team got death threats. A number of prominent men casually threatened her with violence. A week later Joe Pesci hosted SNL and mocked her in the monologue, expressing his wish to give “her such a smack”; Madonna, a famously pious Catholic, appeared as the musical guest a few episodes later and made fun of O’Connor by tearing up a picture of the sex offender Joey Buttafuoco, then a fixture of tabloids and late-night shows. Two weeks after the SNL performance came the Dylan tribute concert.

The SNL performance permanently changed O’Connor’s trajectory. Her A-list status was revoked, though she remained a celebrity in that tabloids considered every aspect of her life grist for their mill. But global superstardom might have inevitably been difficult for O’Connor in the long run. Throughout the documentary she uses similar language to describe the experience of being abused by her mother and that of being mistreated by the media and her peers. Even very early interviews show her grinning uncomfortably and doing her best to respond generously to invasive questions about her hair, her pregnancy, and her schooling. “A lot of people say or think that tearing up the pope’s photo derailed my career,” she writes in Rememberings.

That’s not how I feel about it. I feel that having a number-one record derailed my career and my tearing the photo put me back on the right track. I had to make my living performing live again. And that’s what I was born for.

Made in 2021, when O’Connor was fifty-four, Nothing Compares takes an hour and twenty minutes to reach the end of the SNL controversy, leaving just thirteen minutes for the rest of her recording career, her extensive personal struggles, and the film’s credits. It only does justice to one of the three. The unsatisfying narrative climaxes are brief mentions of the Irish government’s apology to the women of the Magdalene laundries and Ireland’s referendum to legalize gay civil unions. There’s some footage of the band Pussy Riot performing in a Moscow cathedral. Finally there are mentions of the public revelations regarding widespread child abuse by the Catholic Church. O’Connor’s legacy, it seems, is being an artist who stood bravely for what seemed like a lost cause only for history to prove her right.

The film closes with a 2020 television performance of “Thank You for Hearing Me,” from O’Connor’s fourth album, Universal Mother. She is wearing a hijab, though no mention has been made of her embrace of Islam. Between cuts of the performance, a title card explains that the Prince estate denied any use of “Nothing Compares 2 U” in the film. Another title card states that O’Connor continues to write and record music and that “this year sees the release of her 11th studio album.” Then the credits roll. No details are offered about the other albums or the remaining thirty years. What’s missing most from the documentary is a reflection on the work itself, and her artistic development away from center stage.

*

In early 1994 O’Connor had a chart comeback with “You Made Me the Thief of Your Heart,” from the soundtrack to the film In the Name of the Father. Later that year she released Universal Mother. After a brief recording of Germaine Greer talking about the radical potential of women’s unity, the album bursts open with “Fire on Babylon,” one of the most powerful songs in her catalog, with a stunning vocal performance, a grinding beat, and a relentlessly pulsating bass. Most of the album is much less incendiary. “John I Love You,” for example, is a lush, stoned waltz in a higher register than O’Connor usually occupies, full of strings and clavinets and fat left-hand piano chords.

The record’s soft, chamber-music production brought both the intimacy and the occasional awkwardness of her lyrics out from behind jangly guitars and big arrangements. Critical response was mixed, and some of the more vicious digs were directed at the words. When you put it on paper, it’s hard not to wince at “All babies are born saying God’s name over and over.” But a few songs later O’Connor announces in echoing a cappella that “you were born on the day my mother was buried.” The same unguarded style produces both the brutal power of the latter line and the banality of the former. The best tracks on the album, its first and last, work in immaculate counterpoint, opening with O’Connor at her most ferocious and closing with the gracious, soaring dub-hymn “Thank You For Hearing Me.”

O’Connor’s next release, the Gospel Oak EP (1997), is a less hieratic affair than the title suggests, named after the London neighborhood where she went to therapy six days a week while recording. This is a common play in O’Connor’s work: when you think she’s talking about God she’s talking about the world, and when you think she’s talking about the world she’s talking about God. Gospel Oak is largely acoustic and often hushed, its gentle tone hiding some eye-opening lines. (“I love you my hard Englishman,” she sings on “This Is a Rebel Song.” “Your rage is like a fist in my womb.”) The EP draws on at least half a dozen folk traditions and incorporates a number of regional instruments, Uillean pipes intermingling with bouzouki. Irish folk melodies resonate with melodic motifs more common to the Mediterranean and the Middle East, most notably on “4 My Love,” with its hypnotic walking bass and swathes of Greek guitar. The Irish multi-instrumentalist Dónal Lunny, who had contributed to the Riverdance-meets-rembetika sound on a number of Kate Bush records, coproduced Gospel Oak; he was also the father of Shane, O’Connor’s third child, and would later be her primary collaborator on her 2002 album, Sean-Nós Nua.

The three years between Universal Mother and Gospel Oak were one of the longest breaks of O’Connor’s career, but the two releases are close in spirit. They represent her final efforts to reimagine the pop song from the inside. After this point her more left-field experiments (Sean-Nós Nua; Throw Down Your Arms; Theology) would split from her straightforward pop albums.

The best of these exploratory later records is undoubtedly Sean-Nós Nua (“the new old style”), a collection of rearranged traditional Irish folk songs. Sean-nós (“the old style”) refers to a traditional style of unaccompanied, heavily melismatic Irish singing for which some ethnomusicologists have suggested a Mediterranean origin. O’Connor’s new take on the old style includes a full band, and its vibrancy is immediately apparent when comparing O’Connor’s versions with other recordings of the same songs. The highlight of the album is “The Moorlough Shore,” a sighing ballad of loss and regret, the musical and emotional ancestor of songs like Tim Buckley’s “Song to the Siren” and the traditional “House of the Rising Sun” (which O’Connor also recorded).

Of the pop records, the strongest is Faith and Courage (2000), her first full album of original songs since 1994 and her last until 2007, one of the many rebirths and fresh starts that pepper O’Connor’s story: after over a decade with Ensign, in 1998 she left for Atlantic Records. The album has an eclectic list of producers and cowriters, including the Eurythmics’ Dave Stewart, Brian Eno, Wyclef Jean, Kevin “She’kspeare” Briggs, and Adrian Sherwood, who O’Connor dated for a while. Working with leading pop producers often means unconventional songwriters like O’Connor are forced to iron out the quirks and kinks they developed writing alone. “Dancing Lessons,” the Wyclef collaboration, falls flat, and some of Stewart’s productions sound a little dated even for 2000. But in the best case the outcome is her fine cover of “Hold Back the Night” by Robert Hodgens, of the Scottish new wave band The Bluebells, on which the 1980s production sounds authentic rather than expired.

“If anyone truly wants to know me,” she wrote, “the best way is through my songs.” The range and full diversity of her catalog are best showcased by two collections: She Who Dwells in the Secret Place of the Most High Shall Abide Under the Shadow of the Almighty (2003), a collection of rarities, and Collaborations (2005), a collection of collaborations and duets. But her albums remain her most definitive musical statements.

*

I remember being on Tori Amos message boards in 2000 after Amos announced the birth of her first child. Most fans were simply happy for her. But a loud and significant subset speculated grimly about what happiness might do to the singer-songwriter’s creative output. Amos gained fame for the confessional writing on her first two albums, informed by her repressed childhood as the daughter of a preacher and by a sexual assault and its psychic aftermath. Her third album was about the collapse of a long-term relationship. The fourth was about her miscarriage and subsequent marriage to the father. Now that she was happily married and had a child, where would she find the suffering to make good music?

Artists like Amos and O’Connor, who so clearly root their work in biographical pain, are often subjected by critics and fans to this kind of jarring pressure to keep hurting for their art. Any number of moments in O’Connor’s biography—the album of jazz standards; the repeated and inevitably revoked announcements of retirement from music or from recording or from touring—testify that she wanted to break out of this loop. “There would’ve been no point writing and/or going around the world screaming ‘Troy’ into microphones,” she observes in Nothing Compares, “if there wasn’t going to come a day one day that I didn’t need to do that anymore.”

“My collection of albums represents my healing journey,” she writes in Rememberings. “When I was younger, I wrote from a place of pain, because I needed to get things off my chest.” Her penultimate album, How About I Be Me (and You Be You)? (2012), “marked a turning point, which I think began with Sean-Nós Nua and Throw Down Your Arms and Theology; they were stepping stones for me to a place where I didn’t have all this awful shit that I needed to get off my chest.” The journey culminated in her final album, I’m Not Bossy, I’m the Boss (2014), which, she wrote, “I almost consider my first album.”

In the later half of her career, O’Connor’s joy—and her bread and butter—was live performance. “I have supported my four children for third-five years. I supported us by performing live, and I became, if I may say so, a very fine live performer.” Her later tours were well received by fans and critics. “I love performing more than anything else on this planet,” she adds later, “Apart from my children of course.”

Rememberings adds significantly more detail, both about her later life and about her later work, than Nothing Compares, but of its 283 pages 206 are still spent reaching the SNL performance. O’Connor explains in the memoir that after writing the parts of the book leading up to 1992, she had an unrelated breakdown and was hospitalized or under care for a long time before resuming writing. In between significant chunks of her memory had disappeared. Some of what happened across those later years is a matter of disjointed public record. There were mental health struggles, attempts at self-harm, and several stays in psychiatric institutions, including one that led to a grossly exploitative episode of Dr. Phil.

These incidents only encouraged the tone of prurient disdain with which the media spoke about her until her death. In January 2022 her son Shane died at seventeen. The loss isn’t mentioned in the documentary, which was released that fall. The postscript to Rememberings is a letter to her father in which she absolves her parents for blame “for my behavior or mental-health conditions.” “All musicians truly called by God are lunatics,” she tells him. “Otherwise they’d be arrogant bastards.”

Relentlessly exploratory and dedicated to her craft, Sinéad O’Connor was an artist and musician of many talents, but her greatest gift was her voice. At once fierce and mournful, her vocal expositions often feel like she’s summoning something ancient: her cathartic confessions were also a call to prayer. They convey a passion and sincerity that make even her corniest moments somehow revelatory, swathed in a cathedral of reverb and often backed by close, choir-like harmonies. There’s no beauty worth the pain O’Connor suffered, but there’s a lesson in grace and in iron will behind her ability to turn that pain into unspeakably beautiful sound. In Rememberings, she writes:

Some people believe that in heaven it’s always night. I hope so. And I hope if there’s heaven, I qualify (if there’s such a situation as not qualifying). I have a hard time believing God would be cruel. But just in case I deserve otherwise, I hope the fact I’ve sung will make little of my sins.