It starts with a tripod. Two perfectly egg-shaped vessels, bolted neatly together and mounted on legs, deposit three streams of paint—red, blue, and yellow—onto a palette via one of several glassy tentacular funnels. Sitting at a tidy octagonal workbench, a feathered creature with human hands and feet paints birds on a large sheet of paper, a serene smile flickering across its owlish face. The paintbrush is connected to a squat stringed instrument hung around the being’s neck; with its other hand it holds up a prism to refract the starlight streaming brightly through the window. As the light hits the page it animates the painted birds, which fly up and out into the starry night. Against the back wall is a coffee roaster. Even a nonhuman alchemist needs fuel to work wonders through the night.

Encountering any of Remedios Varo’s paintings—this one is Creation of the Birds (1957)—is like opening a musty storybook to a random page and trying, through utter bewilderment, to fill in a plausible before and after for the surreal scene in front of you. Labyrinthine towers are pierced with slit windows, checkerboard floors recede toward a vanishing point, elaborate machines work in perfect order, operated efficiently by beguiling, not-quite-human beings. There’s something of medieval Europe in the austere elegance of the architecture and garments, remnants here and there of Varo’s Spanish convent education, dashes of her immersion in chivalric romance and fantasy literature (Dumas, Lovecraft, Verne, and Poe), and always the influence of Mexico, where she spent the second half of her life.

“Science Fictions” at the Art Institute of Chicago is Varo’s first retrospective in the US since 2000, and an extensive catalog, edited by Caitlin Haskell and Tere Arcq, features copious new research. The works on display were made between 1955—the year before her first solo exhibition, at Mexico City’s Galería Diana, after which Diego Rivera praised her as “among the most important women artists in the world”—and her sudden death in 1963 at the age of fifty-five, a year after her second, legendary solo exhibition. Her work has been featured in a number of posthumous retrospectives and group shows, including the recent “Surrealism Beyond Borders” at the Metropolitan Museum and the Tate Modern, and her life is the subject of a rich and informative 1988 biography by Janet Kaplan. But not until now has such close attention been paid to her meticulous techniques—patiently layering coats of gesso on hardboard, which she covered in scratches for texture before transferring her compositions, in thinned-down oil paint for precision, from full-scale drawings—or the full range of sources, from tarot to Kabbalah to psychoanalysis, which informed her imagery. From her immersion in esoteric philosophies and scientific research emerges the recurring subject of the artist-scientist, whose creative process is depicted as an experiment with the highest of stakes.

*

The great theme of Varo’s art is transformation, often represented by figures embarking on arduous journeys to unknown destinations. It’s a testament to her own continent-spanning life, conditioned by war and exile. María de los Remedios Alicia y Rodriga Varo y Uranga was born in 1908 in Anglès, just north of Barcelona, to a Basque mother and an Andalusian father, a hydraulic engineer whose diagrams and drawings she used to copy as a child. At convent school in Madrid she began to write fantastical stories that often expressed a yearning for escape and which she buried under her bedroom floorboards. Cages appear frequently in her paintings, while floorboards regularly crack open to reveal cats, branches, or streams of light, and walls are liable to burst into human form.

In 1925, at sixteen, she enrolled full-time at the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, the prestigious art academy where Salvador Dalí had matriculated three years earlier, and where she studied anatomy, color theory, and architectural drawing. She encountered the work of modern Surrealists—Federico García Lorca, Luis Buñuel, Dalí—who were starting to build on the fantastical traditions of Goya and Bosch, whose paintings she saw at the Prado. Their influence is evident in the imagery of her earliest drawings and paintings: floating bodies, spiraling staircases, human-plant hybrids. One early work from 1938 shows a pair of eyelash-trimmed glasses on a table, faced down by two unadorned eyeballs; in another, mountains peak into eruptions of foliage and flames.

After a spell in Paris, Varo returned to Republican Barcelona, where she shared studios with other young artists who were pushing boundaries in both their art and their relationships. (After the dissolution of her first marriage, at twenty-one to her fellow student Gerardo Lizarraga, Varo was involved with the Romanian artist Victor Brauner, who lost an eye in a fight over her honor, and in a complex love triangle with Esteban Francés and Benjamin Péret, two Surrealists and activists.) Varo’s primary medium at this time was drawing on paper, but she also experimented with painting on metal and on canvas, as well as exquisite corpse collaborations with like-minded artists. She began to show her drawings and paintings in publications and exhibitions associated with the vanguard Catalan collective Logicofobista—who eschewed reason and order in favor of unconscious associations—and stayed afloat by working in advertising, designing posters for a French confectionary company, and—allegedly—forging paintings to be sold for vast sums as the work of Giorgio de Chirico.

Advertisement

In 1937, with her plans crushed by the bloodshed of the Spanish Civil War, she returned to Paris, where she came into contact with André Breton and a wider circle of international Surrealists who were determined to expand the realm of art beyond waking imagination into the dream world. Surrealism was a philosophy and a call for social change that had developed after World War I, and it was closely associated with Communist and anarchist movements. Under its banner, artists embraced Freud and Marx, experimented with automatism, and sought, as Breton put it in his 1924 manifesto, to express “the actual functioning of thought…in the absence of any control exercised by reason.” Varo was reluctant to see her output reduced to a single label—especially as one of the few women in the notoriously macho movement—but she attended meetings at the café Les Deux Magots, took part in group games, and showed her work in International Surrealist Exhibitions in Paris, Amsterdam, and Tokyo.

When World War II broke out she decided to stay in Paris, loath to return to Franco’s Spain, but in May 1940 Péret was arrested for Communist agitation and taken to a military prison. Varo, too, was detained, a trauma she never publicly discussed. After hiding out with Brauner in a small village in the eastern Pyrenees, where they helped local fishermen haul their nets, Varo managed to reunite with Péret in Marseille. They made their way to a safe house of the Emergency Rescue Committee, an organization set up to expedite the escape of artists and intellectuals from Vichy France, where they waited for their visas with a group that included Breton and Victor Serge, and passed the time making sweets and costumes and playing games of exquisite corpse. In November 1941 they set sail to Mexico, which had opened its borders to Republican refugees, from Casablanca.

Breton called Mexico “the Surrealist place par excellence,” and Varo came into her own within the artistic and intellectual ferment of Mexico City, among the group of exiled artists who congregated in the elegant old streets of Colonia Roma. The arrival of so many European émigrés caused some consternation among the established community of Mexican artists—Frida Kahlo referred disparagingly to the overly intellectual “bitches of Paris”—but a younger generation, led by José Luis Cuevas and his Generación de la Ruptura, was intrigued by the challenge Surrealism posed to the dominant revolutionary socialist mode exemplified by the muralists Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros. Varo admired Kahlo, whom she had met in Paris, and shared Rivera’s fascination with Mexico’s Mesoamerican history and indigenous traditions, traveling the country collecting and restoring pre-Columbian ceramics. Her affinity for her adopted country extended to its landscape: like many artists, she was captivated by the eruption of the Parícutin volcano in 1943, and its dramatic plumes of smoke, geological ruptures, and mountainous form manifested in both the subject matter and rugged surfaces of her paintings.

Varo established immediate affinities with the British painter and writer Leonora Carrington and the Hungarian-born photographer Kati Horna, and they were soon known collectively as the three witches. In their kitchens they transcribed their dreams, created recipes that doubled as ritual performance (“caviar” from tapioca pearls dyed with squid ink and dream-stimulating elixirs of garlic and honey), wrote gender-bending plays and short stories, and read tarot. They studied Mexican folk traditions with the archaeologist and radical Laurette Séjourné, whom they accompanied on fieldwork visiting local healers and shamans in Oaxaca, and attended art workshops run by Christopher Fremantle, a disciple of the Armenian philosopher George Gurdjieff.

Their interest in ancient yet marginalized bodies of knowledge was a feminist response to the militarism that had marked their lives, as well as a way into new realms beyond the seen world, a tantalizing prospect for Surrealist thinkers. Varo and Carrington shared a passion for the literature of myth and magic; among the tomes they pored over were Robert Graves’s The White Goddess, Grillot de Givry’s Illustrated Anthology of Sorcery, Magic and Alchemy, Gerald Gardner’s The Meaning of Witchcraft, and Pauwels and Bergier’s The Morning of the Magicians. These collaborative friendships were of great emotional and intellectual significance to Varo’s life and her art, but she created her paintings in her own private domain, from detailed preparatory drawings made over long solitary hours in her home studio, with the door open onto the terrace to catch the day’s light.

Advertisement

*

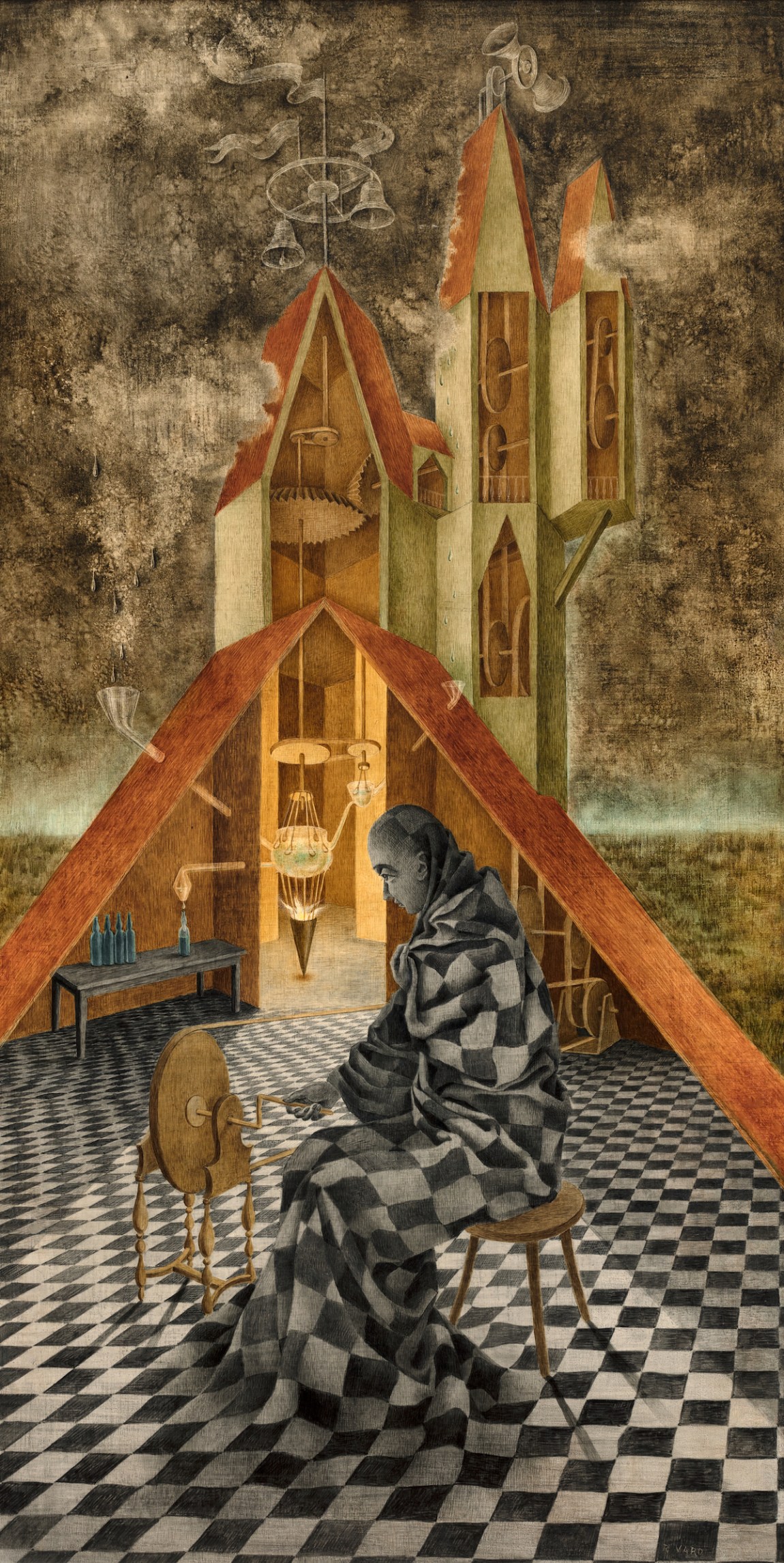

Varo was fascinated by alchemy, which is associated with spiritual transformation (often expressed, in material terms, by the quest to turn matter into gold, or discover a potion that will grant immortality) and seemed to combine her mystical and scientific interests into one overarching philosophy. Figures at work, seeking knowledge and new forms, populate her paintings: alchemists, of sorts, seeking higher purpose through their artistic or scientific labors. Useless Science—which Varo referred to as “The Woman Alchemist”—shows a figure in a checked cloak that billows up from the floor, turning a crank that activates a run of cogs in the turrets behind her, which in turn distill liquid into a row of green bottles. In Harmony (the alternative title is Suggestive Self-Portrait), a figure sits at a table in a crumbling tower room, threading a floating stave with an array of tiny objects: a crystal, a scrap of paper with the first five digits of pi, a leaf. “I deliberately set out to make a mystical work,” Varo said in a 1962 interview, “in the sense of revealing a mystery, or better, of expressing it through ways that do not always correspond to the logical order, but to an intuitive, divinatory and irrational order.” The central figure, she wrote in a letter to her brother, “is trying to find the invisible thread that unites all things.”

This idea, that all systems emerge from a common source, is a tenet of Gurdjieff’s Ray of Creation, a cosmology in which the universe contains eight levels, of which the earth is just one. Gurdjieff considered music to be a means to unlocking the higher state of consciousness to which he believed all humans could aspire, and he taught that art, like alchemy, is capable of effecting physical change in the world. Varo’s work is scattered with references to Gurdjieff’s ideas, and many of her most accomplished alchemists are musicians. In Solar Music (1955), a figure draws a bow across a sunbeam while red birds—recalling the alchemist’s symbol for the soul’s separation from the body—burst from glass cases cracked by the sound. Just as the feathered painter in Creation of the Birds brings birds to life through a merging of artistry and science, so the musician of The Flautist (1955) builds a tower by playing his flute to fossils which respond by flying into place. Inside the half-formed structure is a long staircase ascending to an infinitesimal apex, hinting at the musician’s own pathway to a higher realm of understanding. The levitating fossils recall the floating balls in The Juggler (The Magician) (1956), in which a troupe of cloaked figures stand mesmerized before a magician, who evokes the first card of the Major Arcana in tarot. He stands on a cart topped with billowing sails, herbal remedies spread on a cloth before him. As if to underscore his higher consciousness in material form, the magician’s face is painted on a pentagon of mother-of-pearl inset in the wooden panel.

Varo saw no contradiction between her study of mysticism and her engagement with secular science, nor in her refusal to discriminate between the practices of fine and commercial art. Between 1943 and 1949 she illustrated promotional literature for the pharmaceutical firm Casa Bayer, advertising sleeping pills with disembodied eyes and cures for rheumatism with a bandaged figure pierced by needles, blundering toward a castle through a landscape of spikes and thorns. She spent a year in Venezuela, during which she made technical drawings of giant insects for the malaria division of the public health ministry and traveled down the Orinoco River in search of gold. Her exposure to scientific institutions and processes was significant for her practice, though she retained enough skepticism toward their jargon and pomposity to satirize them in several works. In 1959 she created Homo Rodans, a ducklike skeleton whose spine curves into a wheel, assembled from small bones leftover from cooking stock. The sculpture, which was displayed for years in a music shop in Mexico City that was run by Varo’s third husband, Walter Gruen, was accompanied by a text purportedly written by a professor overturning a colleague’s theory about the species, with references to carbon-dated umbrellas and excavations carried out by trained moles. Homo Rodans captures her fascination with technological evolution, with transformed, gender-defying bodies, and with wheels. In alchemy, the circle represents celestial unity; in reality, the car or bicycle represents quick escape. Many of her paintings depict journeys in small caravans, boats, or other cocoon-like vessels, along floating roads or through forests; there’s a rootlessness to her figures, who seem to be striving in isolation against unseen forces. But violence and conflict are absent from her surfaces: her characters’ struggles are toward self-knowledge and empowerment in whatever form that might take.

In 1960 Varo began work on a dreamlike triptych that she described as three scenes from the life of a young woman who “resists hypnosis.” The three paintings were shown together only once in her lifetime, and they are the only instance in which she used multiple panels to tell a story, a form that recalls the vita icon from Byzantine art. The first, Toward the Tower, shows a group of girls on bicycles following a mother superior and a man with a sack of birds out of a hive-like building; one of the girls looks out at the viewer, as if sharing secret knowledge or seeking a coconspirator, while her companions remain in a trance. The next, Embroidering the Earth’s Mantle, shows a kind of medieval scriptorium in a high tower, where the girls weave and embroider a landscape onto a continuous piece of fabric. A masked figure stands in their midst, reading instructions while stirring the vessel from which they draw their thread. Varo was inspired by a dream of Horna’s about a troupe of girls storming a tower, as well as René Daumal’s novel Mount Analogue, about twelve mountaineers seeking “higher humanity” in the form of a golden flower by climbing up a mountain that links earth and heaven. Another influence on the work was Carrington’s novel The Hearing Trumpet (completed in 1950, though not published until 1974), a satire of Gurdjieffian principles in which Carrington and Varo feature as two nonagenarians who escape from a medieval castle and embark on a high-octane search for the Holy Grail.

In The Crying of Lot 49, Thomas Pynchon described a woman weeping upon seeing Embroidering the Earth’s Mantle, the “frail girls…prisoners in the top room of a circular tower…seeking hopelessly to fill the void.” But the girls are far from powerless. In the folds of material that flow from the tower to the courtyards, towers, and seas far below, one has embroidered a surreptitious symbol of her own liberation: two figures, barely discernible, stealing away from the tower. The third painting of the triptych shows the same couple sailing serenely through swirls of golden mist toward craggy mountains in the distance. The artist, like the alchemist, has made her own escape.