Two weeks ago, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court overturned its own 1985 precedent to rule that the state’s provisions for equal treatment of citizens, including its Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), could apply to abortion rights. At immediate issue is the question of coverage for abortion care under the state’s Medicaid program. Now the lower state courts need to reconsider the case: in light of the guidance they have received from the justices who sit above them, they are quite likely to rule that depriving low-income women of Medicaid coverage for their abortions violates the state constitution. The Hyde Amendment, attached to every federal budget bill since 1976, still forbids the spending of any federal funds for abortion, but if such a ruling goes through, women in Pennsylvania who qualify for the program will have their abortion care covered by state-only Medicaid funds.

It’s no small development for three justices out of five on the highest court of the country’s fifth most populous state to rule that their predecessors made a mistake when they deemed it constitutional to deprive low-income women—and any low-income person who can become pregnant—of abortion coverage. (The appellants included three branches of Planned Parenthood, of whose Vermont Action Fund I am vice-president.) The judges cited the state’s general commitment to provide all its citizens equal protection of the laws as well as its Equal Rights Amendment, one of twenty-two state-level ERAs across the country, which underlines a commitment to equality on the basis of sex and has no national-level analogue. Two of them went further, finding that the state’s ERA encompassed access to abortion in general; a third indicated that he might well be willing to rule that the state ERA covered abortion after the lower courts had considered the case a second time: “The majority’s incredibly insightful position may ultimately prevail in the end.”

The precedent that Pennsylvania just toppled relied on the Supreme Court’s egregious ruling in Harris v. McRae (1980), which found the Hyde Amendment constitutional. Writing for a bare majority, Justice Potter Stewart concluded that the Amendment placed “no governmental obstacle in the path of a woman who chooses to terminate her pregnancy” but simply expressed a governmental preference that the pregnant person make a different choice. A constitutionally guaranteed right to choose abortion, he added, carried with it no “entitlement to the financial resources to avail [oneself] of the full range of protected choices.” The judges who voted in the minority dissented sharply. A scribbled note on the case by Justice Harry Blackmun, the primary author of the majority opinion in Roe v. Wade, appears to read: “& so ends the ballgame.”

By rejecting the logic of Harris v. McRae, the Pennsylvania court has helped reopen questions that for decades neither our courts nor our political system have been willing to confront head-on. Those questions concern the relevance of three forms of discrimination to abortion and gender-based rights: discrimination on the basis of income or insurance status; discrimination on the basis of sex or capacity to get pregnant; and the particular, “intersectional” discrimination against people who can get pregnant and have incomes low enough to qualify for health insurance through Medicaid.1 More broadly speaking, the Pennsylvania decision reopens the possibility of considering abortion rights as a matter of equality—a matter of guaranteeing both the general promise of “equal protection of the laws” under the Fourteenth Amendment and the specific promise, from Pennsylvania’s and other state constitutions, that the government will not deny rights “because of the sex of the individual.” If more state supreme courts follow suit, it could be significantly easier to anchor abortion rights in constitutional principles within the states, even if neither the Supreme Court nor Congress becomes any more liberal or functional than they are today.

*

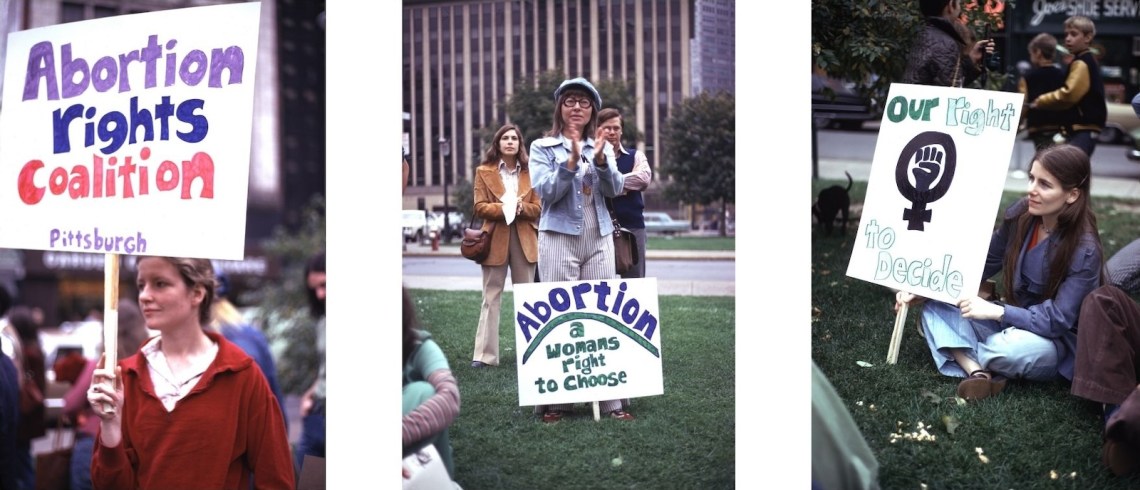

We tend to associate abortion rights with concepts most familiar from Roe v. Wade: liberty and privacy, for both medical personnel and patients. These are important principles, but in the years before Roe claims for equality on the basis of sex, more than privacy, were at the heart of the struggle. Participants in a women’s movement committed to ending subordination on the basis of sex or gender were largely the ones responsible for challenging the constitutionality of state abortion bans, and ultimately forcing the US Supreme Court to resolve the issue. Among them was my mother, Beatrice Kornbluh Braun, a member of the then-recently founded National Organization for Women, who in late 1968 drafted a law for the New York state legislature that would have repealed all abortion restrictions—setting the stage for what would become the most ambitious abortion-legalization law in the country in the years before Roe.

My mother drafted that law out of a conviction that access to abortion, a safe and relatively straightforward procedure even in the late 1960s, was a matter of simple fairness between those who can get pregnant and those who cannot. Shell games about medical exception like the ones now playing out in Texas—where last December the state supreme court refused to allow a woman named Kate Cox to receive an abortion even after her fetus was diagnosed with a condition that meant it would likely die in utero or soon after birth—pretend to allow for compassion and common sense, but they effectively rob pregnant people of dignity, safety, and self-determination. For my mother, equality meant removing barriers to medical decision-making, not least because they impede equal access to education, employment, and political participation. It was a commitment that emerged from her broader work for economic and racial justice; she was among the activists who tried to pull the Democratic Party away from Southern segregationists and toward the movement for Black civil rights. Advocates like her believed not only that the government had to leave us alone—the assumption at the center of privacy arguments—but also that it had to deliver on its promise of fair and equal treatment.

Advertisement

By this logic, ensuring equal treatment meant struggling against discrimination on the basis both of income and of gender or sex. The idea that poverty and economic inequality were sources of invidious discrimination was central to the movement for legal “welfare rights” in the 1960s and early 1970s, which was closely tied to a grassroots welfare-rights movement and the national War on Poverty. In the early 1970s, however, federal courts signaled that they were unwilling to do much about inequalities of wealth and income—decisions that helped lay the groundwork for rulings like McRae and policy innovations such as the Reagan administration’s cuts to social programs and Bill Clinton’s “welfare reform.”2 Discussions of income or wealth discrimination are still relatively marginal in our legal culture, but in the years since Occupy Wall Street and the Bernie Sanders campaigns they have come to seem less far-out.

Opposition to discrimination on the basis of sex or gender, meanwhile, was just hitting its stride in the 1970s, thanks in part to the work of the law professor and ACLU advocate Ruth Bader Ginsburg. The Supreme Court acknowledged that there was such a thing as discrimination on the basis of sex for the first time in Reed v. Reed (1971), a doctrinal milestone, although it resolved only a narrow question about whether a state government could designate men over women as the executors of estates. But by 1974 the Court was already backing away from some of the implications of the idea of sex-based discrimination, ruling in Geduldig v. Aiello (a case that Justice Samuel Alito cited in his opinion overruling Roe) that pregnancy discrimination was not necessarily sex discrimination—if the government engaged in discrimination for economic reasons. The Harris v. McRae decision built on the logic of that earlier one, legalizing the fiction that a person could exercise their reproductive rights and have access to full citizenship if their publicly funded health care placed abortion access out of their financial reach.

In the aftermath of these setbacks, many legal scholars and activists have struggled to get courts to recognize how either of these forms of discrimination might bear on abortion rights, and despaired of ever getting courts to recognize the intersectional combination of the two. Yet now the top court of a populous state is implicitly recognizing the particular legal needs of people who are disadvantaged in two ways at once, by poverty and gender. They never say as much, but the justices in the majority on the Pennsylvania court may well have learned from feminist writing arguing that equality was a more robust and appropriate anchor for abortion rights than liberty or privacy.3 This writing includes decades of statements by the late Justice Ginsburg as well as an amicus curiae brief to the Supreme Court in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, in which the scholars Serena Mayeri, Melissa Murray, and Reva Siegel argued that access to abortion was a matter of equal protection and that the Mississippi legislation under consideration in that case was unconstitutional because it represented a prohibited legal action toward a protected group.

Asked in 2018 about future directions in the legal effort to protect abortion rights, Ginsburg herself brought up the McRae case and the joined issues of distinctions based on sex and income. Justice Ginsburg said she was “surprised” that “the Supreme Court rejected the equality plea” in McRae. In the future, she suggested, “state courts might be more sympathetic to the argument that choice means choice for all women, not just women with the means to pay for the services they seek.”4

*

This past October Ms. magazine, the Feminist Majority Foundation, and Lake Research Partners polled American voters on their support for abortion rights. They found that 74 percent favor the right to make our own decisions about reproductive health care. But the poll also found strong support for the Equal Rights Amendment, including from 72 percent of independents and 46 percent of Republicans—a more surprising outcome than it might seem. The pitched debate over the passage of a federal ERA in the 1970s—during which Phyllis Schlafly and other conservative critics argued it would have unexpectedly radical effects, like mandating all-gender bathrooms, same-sex marriages, and women’s mandatory military service—and the notorious failure of the law’s advocates to secure ratification have long dampened public support for the ERA. Now that support seems to be on the rise, especially in combination with abortion rights. The two are “strong turnout issues” on their own, the groups concluded, but they would be “even more powerful when combined,” especially for young women, women unaffiliated with either party, Black and Latina voters, and voters in their thirties.

Advertisement

This November, as I noted recently in The American Prospect, citizens of New York will get to vote on a state-level ERA that forbids government officials from discriminating on the basis of ethnicity, national origin, age, disability, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, pregnancy, or pregnancy outcomes. New York is hardly the only state where abortion rights are, or have recently been, on the ballot. Six states have had abortion-related ballot measures since Dobbs v. Jackson in 2022, and all of them have produced abortion-rights wins. Maryland voters will also have a chance to vote on abortion rights in November, and Florida’s Supreme Court justices are deciding now whether voters will have a chance to consider an abortion measure that has enough signatures to get on the ballot. There could be as many as nine additional measures in states across the country. These proposals and the rhetoric around them will likely differ widely from one another; one reason for the movement’s winning record is its local rootedness. In my home state of Vermont, for example, a sweeping “Reproductive Liberty Amendment” won in every single town, probably because its advocates appealed to the state’s left-libertarian commitment to keeping the government out of our private lives.

Meanwhile the public has recently gotten a series of object lessons on what inequality can mean for people who seek to exercise their reproductive rights. In my mother’s time, a quarter of maternal deaths of white women occurred when they attempted to abort, and fully half of Black and Puerto Rican women’s maternal deaths were abortion-related. The fallout from Dobbs is still unfolding, but the advocacy group If/When/How reports that most pregnancy-related prosecutions since 2020 have been of women of color, immigrants, or low-income people.5 This year Brittany Watts, a Black woman in Ohio, was accused of a felony for having supposedly abused a corpse after enduring a miscarriage; she was reported to authorities by a hospital nurse who appears to have believed that Watts took medications to bring on her miscarriage. The attempt to prosecute her—which ultimately failed—was in this sense a form of abortion criminalization by proxy, even though Ohio’s citizens voted overwhelmingly for abortion rights last November.

In response to equality arguments from Mayeri, Murray, and Siegel, as well as from the Biden administration, Justice Alito’s majority decision in Dobbs insisted that there was no sex discrimination involved in Mississippi’s highly restrictive law, since abortion involved members of only one sex. But there is plenty of room in our constitutional traditions to argue that laws like the ones that drove Kate Cox from Texas and allowed for Brittany Watts’s prosecution treat women differently from men (and, in Watts’s case, treat working-class Black women differently from wealthy white women as well). The Supreme Court doesn’t agree that abortion bans violate this country’s constitutional commitment to “equal protection of the laws.” But that shouldn’t prevent state-level activists or judges, or nationally oriented advocates, from insisting otherwise.